Contents

-

(Top)

-

1Terminology

-

2Early history

-

3Improvements at the Volta Laboratory

-

4Disc vs. cylinder as a recording medium

-

5Dominance of the disc record

-

6Arm systems

-

7Pickup systems

-

8Stylus

-

9Record materials

-

10Equalization

-

11In the 21st century

-

12See also

-

13Notes

-

14References

-

15Further reading

-

16External links

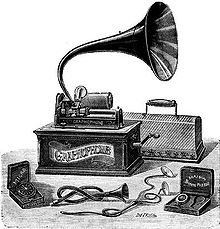

A phonograph, later called a gramophone (as a trademark since 1887, as a generic name in the UK since 1910), and since the 1940s a record player, or more recently a turntable,[a] is a device for the mechanical and analogue reproduction of recorded[b] sound. The sound vibration waveforms are recorded as corresponding physical deviations of a spiral groove engraved, etched, incised, or impressed into the surface of a rotating cylinder or disc, called a "record". To recreate the sound, the surface is similarly rotated while a playback stylus traces the groove and is therefore vibrated by it, very faintly reproducing the recorded sound. In early acoustic phonographs, the stylus vibrated a diaphragm which produced sound waves which were coupled to the open air through a flaring horn, or directly to the listener's ears through stethoscope-type earphones.

The phonograph was invented in 1877 by Thomas Edison.[1][2][3][4] Phonograph use would grow the following year. Alexander Graham Bell's Volta Laboratory made several improvements in the 1880s and introduced the graphophone, including the use of wax-coated cardboard cylinders and a cutting stylus that moved from side to side in a zigzag groove around the record. In the 1890s, Emile Berliner initiated the transition from phonograph cylinders to flat discs with a spiral groove running from the periphery to near the center, coining the term gramophone for disc record players, which is predominantly used in many languages. Later improvements through the years included modifications to the turntable and its drive system, the stylus or needle, pickup system, and the sound and equalization systems.

The disc phonograph record was the dominant commercial audio distribution format throughout most of the 20th century. In the 1960s, the use of 8-track cartridges and cassette tapes were introduced as alternatives. By 1987, phonograph use had declined sharply due to the popularity of cassettes and the rise of the compact disc. However, records have undergone a revival since the late 2000s. This resurgence has much to do with vinyl records' sparing use of audio processing, resulting in a more natural sound on high-quality replay equipment, compared to many digital releases that are highly processed for portable players in high-noise environmental conditions. However, unlike "plug-and-play" digital audio, vinyl record players have user-serviceable parts, which require attention to tonearm alignment and the wear and choice of stylus, the most critical component affecting turntable sound.[5]

Terminology

The terminology used to describe record-playing devices is not uniform across the English-speaking world. In modern contexts, the playback device is often referred to as a "turntable", "record player", or "record changer". Each of these terms denotes distinct items. When integrated into a DJ setup with a mixer, turntables are colloquially known as "decks".[6] In later versions of electric phonographs, commonly known since the 1940s as record players or turntables, the movements of the stylus are transformed into an electrical signal by a transducer. This signal is then converted back into sound through a loudspeaker.[7]

The term "phonograph", meaning "sound writing", originates from the Greek words φωνή (phonē, meaning 'sound' or 'voice') and γραφή (graphē, meaning 'writing'). Similarly, the terms "gramophone" and "graphophone" have roots in the Greek words γράμμα (gramma, meaning 'letter') and φωνή (phōnē, meaning 'voice').

In British English, "gramophone" may refer to any sound-reproducing machine that utilizes disc records. These were introduced and popularized in the UK by the Gramophone Company. Initially, "gramophone" was a proprietary trademark of the company, and any use of the name by competing disc record manufacturers was rigorously challenged in court. However, in 1910, an English court decision ruled that the term had become generic;[8]

United States

In American English, "phonograph", properly specific to machines made by Edison, was sometimes used in a generic sense as early as the 1890s to include cylinder-playing machines made by others. But it was then considered strictly incorrect to apply it to Emile Berliner's Gramophone, a very different machine which played nonrecordable discs (although Edison's original Phonograph patent included the use of discs.[9])

Australia

In Australian English, "record player" was the term; "turntable" was a more technical term; "gramophone" was restricted to the old mechanical (i.e., wind-up) players; and "phonograph" was used as in British English. The "phonograph" was first demonstrated in Australia on 14 June 1878 to a meeting of the Royal Society of Victoria by the Society's Honorary Secretary, Alex Sutherland who published "The Sounds of the Consonants, as Indicated by the Phonograph" in the Society's journal in November that year.[10] On 8 August 1878 the phonograph was publicly demonstrated at the Society's annual conversazione, along with a range of other new inventions, including the microphone.[11]

Early history

Phonautograph

The phonautograph was invented on March 25, 1857, by Frenchman Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville,[12] an editor and typographer of manuscripts at a scientific publishing house in Paris.[13] One day while editing Professor Longet's Traité de Physiologie, he happened upon that customer's engraved illustration of the anatomy of the human ear, and conceived of "the imprudent idea of photographing the word." In 1853 or 1854 (Scott cited both years) he began working on "le problème de la parole s'écrivant elle-même" ("the problem of speech writing itself"), aiming to build a device that could replicate the function of the human ear.[13][14]

Scott coated a plate of glass with a thin layer of lampblack. He then took an acoustic trumpet, and at its tapered end affixed a thin membrane that served as the analog to the eardrum. At the center of that membrane, he attached a rigid boar's bristle approximately a centimetre long, placed so that it just grazed the lampblack. As the glass plate was slid horizontally in a well formed groove at a speed of one meter per second, a person would speak into the trumpet, causing the membrane to vibrate and the stylus to trace figures[13] that were scratched into the lampblack.[15] On March 25, 1857, Scott received the French patent[16] #17,897/31,470 for his device, which he called a phonautograph.[17] The earliest known surviving recorded sound of a human voice was conducted on April 9, 1860, when Scott recorded[15] someone singing the song "Au Clair de la Lune" ("By the Light of the Moon") on the device.[18] However, the device was not designed to play back sounds,[15][19] as Scott intended for people to read back the tracings,[20] which he called phonautograms.[14] This was not the first time someone had used a device to create direct tracings of the vibrations of sound-producing objects, as tuning forks had been used in this way by English physicist Thomas Young in 1807.[21] By late 1857, with support from the Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale, Scott's phonautograph was recording sounds with sufficient precision to be adopted by the scientific community, paving the way for the nascent science of acoustics.[14]

The device's true significance in the history of recorded sound was not fully realized prior to March 2008, when it was discovered and resurrected in a Paris patent office by First Sounds, an informal collaborative of American audio historians, recording engineers, and sound archivists founded to make the earliest sound recordings available to the public. The phonautograms were then digitally converted by scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, who were able to play back the recorded sounds, something Scott had never conceived of. Prior to this point, the earliest known record of a human voice was thought to be an 1877 phonograph recording by Thomas Edison.[15][22] The phonautograph would play a role in the development of the gramophone, whose inventor, Emile Berliner, worked with the phonautograph in the course of developing his own device.[23]

Paleophone

Charles Cros, a French poet and amateur scientist, is the first person known to have made the conceptual leap from recording sound as a traced line to the theoretical possibility of reproducing the sound from the tracing and then to devising a definite method for accomplishing the reproduction. On April 30, 1877, he deposited a sealed envelope containing a summary of his ideas with the French Academy of Sciences, a standard procedure used by scientists and inventors to establish priority of conception of unpublished ideas in the event of any later dispute.[24]

An account of his invention was published on October 10, 1877, by which date Cros had devised a more direct procedure: the recording stylus could scribe its tracing through a thin coating of acid-resistant material on a metal surface and the surface could then be etched in an acid bath, producing the desired groove without the complication of an intermediate photographic procedure.[25] The author of this article called the device a phonographe, but Cros himself favored the word paleophone, sometimes rendered in French as voix du passé ('voice of the past').[citation needed]

Cros was a poet of meager means, not in a position to pay a machinist to build a working model, and largely content to bequeath his ideas to the public domain free of charge and let others reduce them to practice, but after the earliest reports of Edison's presumably independent invention crossed the Atlantic he had his sealed letter of April 30 opened and read at the December 3, 1877 meeting of the French Academy of Sciences, claiming due scientific credit for priority of conception.[26]

Throughout the first decade (1890–1900) of commercial production of the earliest crude disc records, the direct acid-etch method first invented by Cros was used to create the metal master discs, but Cros was not around to claim any credit or to witness the humble beginnings of the eventually rich phonographic library he had foreseen. He had died in 1888 at the age of 45.[27]

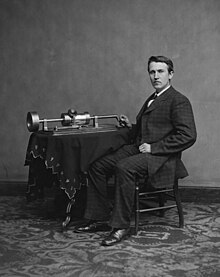

The early phonographs

Thomas Edison conceived the principle of recording and reproducing sound between May and July 1877 as a byproduct of his efforts to "play back" recorded telegraph messages and to automate speech sounds for transmission by telephone.[28] His first experiments were with waxed paper.[29] He announced his invention of the first phonograph, a device for recording and replaying sound, on November 21, 1877 (early reports appear in Scientific American and several newspapers in the beginning of November, and an even earlier announcement of Edison working on a 'talking-machine' can be found in the Chicago Daily Tribune on May 9 [30]), and he demonstrated the device for the first time on November 29 (it was patented on February 19, 1878, as US Patent 200,521). "In December, 1877, a young man came into the office of the Scientific American, and placed before the editors a small, simple machine about which very few preliminary remarks were offered. The visitor without any ceremony whatever turned the crank, and to the astonishment of all present the machine said: 'Good morning. How do you do? How do you like the phonograph?' The machine thus spoke for itself, and made known the fact that it was the phonograph..."[31]

The music critic Herman Klein attended an early demonstration (1881–2) of a similar machine. On the early phonograph's reproductive capabilities he writes "It sounded to my ear like someone singing about half a mile away, or talking at the other end of a big hall; but the effect was rather pleasant, save for a peculiar nasal quality wholly due to the mechanism, though there was little of the scratching which later was a prominent feature of the flat disc. Recording for that primitive machine was a comparatively simple matter. I had to keep my mouth about six inches away from the horn and remember not to make my voice too loud if I wanted anything approximating to a clear reproduction; that was all. When it was played over to me and I heard my own voice for the first time, one or two friends who were present said that it sounded rather like mine; others declared that they would never have recognised it. I daresay both opinions were correct."[32]

The Argus newspaper from Melbourne, Australia, reported on an 1878 demonstration at the Royal Society of Victoria, writing "There was a large attendance of ladies and gentlemen, who appeared greatly interested in the various scientific instruments exhibited. Among these the most interesting, perhaps, was the trial made by Mr. Sutherland with the phonograph, which was most amusing. Several trials were made, and were all more or less successful. "Rule Britannia" was distinctly repeated, but great laughter was caused by the repetition of the convivial song of "He's a jolly good fellow," which sounded as if it was being sung by an old man of 80 with a very cracked voice."[33]

Early machines

Edison's early phonographs recorded onto a thin sheet of metal, normally tinfoil, which was temporarily wrapped around a helically grooved cylinder mounted on a correspondingly threaded rod supported by plain and threaded bearings. While the cylinder was rotated and slowly progressed along its axis, the airborne sound vibrated a diaphragm connected to a stylus that indented the foil into the cylinder's groove, thereby recording the vibrations as "hill-and-dale" variations of the depth of the indentation.[34]

Introduction of the disc record

By 1890, record manufacturers had begun using a rudimentary duplication process to mass-produce their product. While the live performers recorded the master phonograph, up to ten tubes led to blank cylinders in other phonographs. Until this development, each record had to be custom-made. Before long, a more advanced pantograph-based process made it possible to simultaneously produce 90–150 copies of each record. However, as demand for certain records grew, popular artists still needed to re-record and re-re-record their songs. Reportedly, the medium's first major African-American star George Washington Johnson was obliged to perform his "The Laughing Song" (or the separate "The Whistling Coon")[35] literally thousands of times in a studio during his recording career. Sometimes he would sing "The Laughing Song" more than fifty times in a day, at twenty cents per rendition. (The average price of a single cylinder in the mid-1890s was about fifty cents.)[citation needed]

Oldest surviving recordings

Lambert's lead cylinder recording for an experimental talking clock is often identified as the oldest surviving playable sound recording,[36] although the evidence advanced for its early date is controversial.[37] Wax phonograph cylinder recordings of Handel's choral music made on June 29, 1888, at The Crystal Palace in London were thought to be the oldest-known surviving musical recordings,[38] until the recent playback by a group of American historians of a phonautograph recording of Au clair de la lune made on April 9, 1860.[39]

The 1860 phonautogram had not until then been played, as it was only a transcription of sound waves into graphic form on paper for visual study. Recently developed optical scanning and image processing techniques have given new life to early recordings by making it possible to play unusually delicate or physically unplayable media without physical contact.[40]

A recording made on a sheet of tinfoil at an 1878 demonstration of Edison's phonograph in St. Louis, Missouri, has been played back by optical scanning and digital analysis. A few other early tinfoil recordings are known to survive, including a slightly earlier one which is believed to preserve the voice of U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes, but as of May 2014 they have not yet been scanned.[clarification needed] These antique tinfoil recordings, which have typically been stored folded, are too fragile to be played back with a stylus without seriously damaging them. Edison's 1877 tinfoil recording of Mary Had a Little Lamb, not preserved, has been called the first instance of recorded verse.[41]

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the phonograph, Edison recounted reciting Mary Had a Little Lamb to test his first machine. The 1927 event was filmed by an early sound-on-film newsreel camera, and an audio clip from that film's soundtrack is sometimes mistakenly presented as the original 1877 recording.[42] Wax cylinder recordings made by 19th-century media legends such as P. T. Barnum and Shakespearean actor Edwin Booth are amongst the earliest verified recordings by the famous that have survived to the present.[43][44]

Improvements at the Volta Laboratory

Alexander Graham Bell and his two associates took Edison's tinfoil phonograph and modified it considerably to make it reproduce sound from wax instead of tinfoil. They began their work at Bell's Volta Laboratory in Washington, D. C., in 1879, and continued until they were granted basic patents in 1886 for recording in wax.[45]

Although Edison had invented the phonograph in 1877, the fame bestowed on him for this invention was not due to its efficiency. Recording with his tinfoil phonograph was too difficult to be practical, as the tinfoil tore easily, and even when the stylus was properly adjusted, its reproduction of sound was distorted, and good for only a few playbacks; nevertheless Edison had discovered the idea of sound recording. However immediately after his discovery he did not improve it, allegedly because of an agreement to spend the next five years developing the New York City electric light and power system.[45]

Volta's early challenge

Meanwhile, Bell, a scientist and experimenter at heart, was looking for new worlds to conquer after having patented the telephone. According to Sumner Tainter, it was through Gardiner Green Hubbard that Bell took up the phonograph challenge. Bell had married Hubbard's daughter Mabel in 1879 while Hubbard was president of the Edison Speaking Phonograph Co., and his organization, which had purchased the Edison patent, was financially troubled because people did not want to buy a machine which seldom worked well and proved difficult for the average person to operate.[45]

Volta Graphophone

The sound vibrations had been indented in the wax which had been applied to the Edison phonograph. The following was the text of one of their recordings: "There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamed of in your philosophy. I am a Graphophone and my mother was a phonograph."[46] Most of the disc machines designed at the Volta Lab had their disc mounted on vertical turntables. The explanation is that in the early experiments, the turntable, with disc, was mounted on the shop lathe, along with the recording and reproducing heads. Later, when the complete models were built, most of them featured vertical turntables.[45]

One interesting exception was a horizontal seven inch turntable. The machine, although made in 1886, was a duplicate of one made earlier but taken to Europe by Chichester Bell. Tainter was granted U.S. patent 385,886 on July 10, 1888. The playing arm is rigid, except for a pivoted vertical motion of 90 degrees to allow removal of the record or a return to starting position. While recording or playing, the record not only rotated, but moved laterally under the stylus, which thus described a spiral, recording 150 grooves to the inch.[45]

The basic distinction between the Edison's first phonograph patent and the Bell and Tainter patent of 1886 was the method of recording. Edison's method was to indent the sound waves on a piece of tin foil, while Bell and Tainter's invention called for cutting, or "engraving", the sound waves into a wax record with a sharp recording stylus.[45]

Graphophone commercialization

In 1885, when the Volta Associates were sure that they had a number of practical inventions, they filed patent applications and began to seek out investors. The Volta Graphophone Company of Alexandria, Virginia, was created on January 6, 1886, and incorporated on February 3, 1886. It was formed to control the patents and to handle the commercial development of their sound recording and reproduction inventions, one of which became the first Dictaphone.[45]

After the Volta Associates gave several demonstrations in the City of Washington, businessmen from Philadelphia created the American Graphophone Company on March 28, 1887, in order to produce and sell the machines for the budding phonograph marketplace.[47] The Volta Graphophone Company then merged with American Graphophone,[47] which itself later evolved into Columbia Records.[48][49]

A coin-operated version of the Graphophone, U.S. patent 506,348, was developed by Tainter in 1893 to compete with nickel-in-the-slot entertainment phonograph U.S. patent 428,750 demonstrated in 1889 by Louis T. Glass, manager of the Pacific Phonograph Company.[50]

The work of the Volta Associates laid the foundation for the successful use of dictating machines in business, because their wax recording process was practical and their machines were durable. But it would take several more years and the renewed efforts of Edison and the further improvements of Emile Berliner and many others, before the recording industry became a major factor in home entertainment.[45]

Disc vs. cylinder as a recording medium

Discs (that aren't re-recordable) are not inherently better than cylinders at providing audio fidelity. Rather, the advantages of the format are seen in the manufacturing process: discs can be stamped, and the matrixes to stamp disc can be shipped to other printing plants for a global distribution of recordings; cylinders could not be stamped until 1901–1902, when the gold moulding process was introduced by Edison.[51]

Through experimentation, in 1892 Berliner began commercial production of his disc records and "gramophones". His "gramophone record" was the first disc record to be offered to the public. They were five inches (13 cm) in diameter and recorded on one side only. Seven-inch (17.5 cm) records followed in 1895. Also in 1895 Berliner replaced the hard rubber used to make the discs with a shellac compound.[52] Berliner's early records had very poor sound quality, however. Work by Eldridge R. Johnson eventually improved the sound fidelity to a point where it was as good as the cylinder.[53]

Dominance of the disc record

In the 1930s, vinyl (originally known as vinylite) was introduced as a record material for radio transcription discs, and for radio commercials. At that time, virtually no discs for home use were made from this material. Vinyl was used for the popular 78-rpm V-discs issued to US soldiers during World War II. This significantly reduced breakage during transport. The first commercial vinylite record was the set of five 12" discs "Prince Igor" (Asch Records album S-800, dubbed from Soviet masters in 1945). Victor began selling some home-use vinyl 78s in late 1945; but most 78s were made of a shellac compound until the 78-rpm format was completely phased out. (Shellac records were heavier and more brittle.) 33s and 45s were, however, made exclusively of vinyl, with the exception of some 45s manufactured out of polystyrene.[54]

First all-transistor phonograph

In 1955, Philco developed and produced the world's first all-transistor phonograph models TPA-1 and TPA-2, which were announced in the June 28, 1955 edition of The Wall Street Journal.[55] Philco started to sell these all-transistor phonographs in the fall of 1955, for the price of $59.95. The October 1955 issue of Radio & Television News magazine (page 41), had a full page detailed article on Philco's new consumer product. The all-transistor portable phonograph TPA-1 and TPA-2 models played only 45rpm records and used four 1.5 volt "D" batteries for their power supply. The "TPA" stands for "Transistor Phonograph Amplifier". Their circuitry used three Philco germanium PNP alloy-fused junction audio frequency transistors. After the 1956 season had ended, Philco decided to discontinue both models, for transistors were too expensive compared to vacuum tubes,[56][57] but by 1961 a $49.95 ($509.29 in 2023) portable, battery-powered radio-phonograph with seven transistors was available.[58]

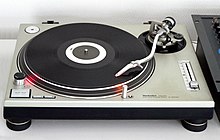

First direct-drive turntable

The direct-drive turntable was invented by Shuichi Obata, an engineer at Matsushita (now Panasonic).[59] In 1969, Matsushita released it as the Technics SP-10,[60] the first direct-drive turntable on the market.[61]

The most influential direct-drive turntable was the Technics SL-1200,[62] which, following the spread of turntablism in hip hop culture, became the most widely-used turntable in DJ culture for several decades.[62]

Cue lever

More sophisticated turntables were (and still are) frequently manufactured so as to incorporate a "cue lever", a device which mechanically lowers the tonearm on to the record. It enables the user to locate an individual track more easily, to pause a record, and to avoid the risk of scratching the record which it may take practice to avoid when lowering the tonearm manually.[63]

Arm systems

In some high quality equipment the arm carrying the pickup, known as a tonearm, is manufactured separately from the motor and turntable unit. Companies specialising in the manufacture of tonearms include the English company SME.

Linear tracking

Early developments in linear turntables were from Rek-O-Kut (portable lathe/phonograph) and Ortho-Sonic in the 1950s, and Acoustical in the early 1960s. These were eclipsed by more successful implementations of the concept from the late 1960s through the early 1980s.[64]

Pickup systems

The pickup or cartridge is a transducer that converts mechanical vibrations from a stylus into an electrical signal. The electrical signal is amplified and converted into sound by one or more loudspeakers. Crystal and ceramic pickups that use the piezoelectric effect have largely been replaced by magnetic cartridges.

The pickup includes a stylus with a small diamond or sapphire tip which runs in the record groove. The stylus eventually becomes worn by contact with the groove, and it is usually replaceable.

Styli are classified as spherical or elliptical, although the tip is actually shaped as a half-sphere or a half-ellipsoid. Spherical styli are generally more robust than other types, but do not follow the groove as accurately, giving diminished high frequency response. Elliptical styli usually track the groove more accurately, with increased high frequency response and less distortion. For DJ use, the relative robustness of spherical styli make them generally preferred for back-cuing and scratching. There are a number of derivations of the basic elliptical type, including the shibata or fine line stylus, which can more accurately reproduce high frequency information contained in the record groove. This is especially important for playback of quadraphonic recordings.[65]

Optical readout

A few specialist laser turntables read the groove optically using a laser pickup. Since there is no physical contact with the record, no wear is incurred. However, this "no wear" advantage is debatable, since vinyl records have been tested to withstand even 1200 plays with no significant audio degradation, provided that it is played with a high quality cartridge and that the surfaces are clean.[66]

An alternative approach is to take a high-resolution photograph or scan of each side of the record and interpret the image of the grooves using computer software. An amateur attempt using a flatbed scanner lacked satisfactory fidelity.[67] A professional system employed by the Library of Congress produces excellent quality.[68]

Stylus

A development in stylus form came about by the attention to the CD-4 quadraphonic sound modulation process, which requires up to 50 kHz frequency response, with cartridges like Technics EPC-100CMK4 capable of playback on frequencies up to 100 kHz. This requires a stylus with a narrow side radius, such as 5 µm (or 0.2 mil). A narrow-profile elliptical stylus is able to read the higher frequencies (greater than 20 kHz), but at an increased wear, since the contact surface is narrower. For overcoming this problem, the Shibata stylus was invented around 1972 in Japan by Norio Shibata of JVC.[69]

The Shibata-designed stylus offers a greater contact surface with the groove, which in turn means less pressure over the vinyl surface and thus less wear. A positive side effect is that the greater contact surface also means the stylus will read sections of the vinyl that were not touched (or "worn") by the common spherical stylus. In a demonstration by JVC[70] records "worn" after 500 plays at a relatively very high 4.5 gf tracking force with a spherical stylus, played "as new" with the Shibata profile.[citation needed]

Other advanced stylus shapes appeared following the same goal of increasing contact surface, improving on the Shibata. Chronologically: "Hughes" Shibata variant (1975),[71] "Ogura" (1978),[72] Van den Hul (1982).[73] Such a stylus may be marketed as "Hyperelliptical" (Shure), "Alliptic", "Fine Line" (Ortofon), "Line contact" (Audio Technica), "Polyhedron", "LAC", or "Stereohedron" (Stanton).[74]

A keel-shaped diamond stylus appeared as a byproduct of the invention of the CED Videodisc. This, together with laser-diamond-cutting technologies, made possible the "ridge" shaped stylus, such as the Namiki (1985)[75] design, and Fritz Gyger (1989)[76] design. This type of stylus is marketed as "MicroLine" (Audio technica), "Micro-Ridge" (Shure), or "Replicant" (Ortofon).[74]

Record materials

To address the problem of steel needle wear upon records, which resulted in the cracking of the latter, RCA Victor devised unbreakable records in 1930, by mixing polyvinyl chloride with plasticisers, in a proprietary formula they called Victrolac, which was first used in 1931, in motion picture discs.[77]

Equalization

Since the late 1950s, almost all phono input stages have used the RIAA equalization standard. Before settling on that standard, there were many different equalizations in use, including EMI, HMV, Columbia, Decca FFRR, NAB, Ortho, BBC transcription, etc. Recordings made using these other equalization schemes will typically sound odd if they are played through a RIAA-equalized preamplifier. High-performance (so-called "multicurve disc") preamplifiers, which include multiple, selectable equalizations, are no longer commonly available. However, some vintage preamplifiers, such as the LEAK varislope series, are still obtainable and can be refurbished. Newer preamplifiers like the Esoteric Sound Re-Equalizer or the K-A-B MK2 Vintage Signal Processor are also available.[78]

In the 21st century

Although largely replaced since the introduction of the compact disc in 1982, record albums still sold in small numbers throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Starting in the late 2000s, record sales began to grow: in 2008, LP sales grew by 90% over 2007, with 1.9 million records sold.[79]

Turntables continued to be manufactured and sold in the 2010s, although in small numbers. While some people still like the sound of vinyl records over that of digital music sources (mainly compact discs), they represent a minority of listeners. As of 2015, the sale of vinyl LPs has increased 49–50% percent from the previous year, although small in comparison to the sale of other formats which although more units were sold (Digital Sales, CDs) the more modern formats experienced a decline in sales.[80] In 2017, vinyl LP sales were slightly decreased, at a rate of 5%, in comparison to previous years' numbers, regardless of the noticeable rise of vinyl records sales worldwide.[81] In 2022, vinyl sales surpassed CD sales for the first time since 1987: 41 million vinyl records were sold, grossing $1.2 billion in revenue, compared to only 33 million CDs sold, amounting to $483 million.[82]

USB turntables have a built-in audio interface, which transfers the sound directly to the connected computer.[83] Some USB turntables transfer the audio without equalization, but are sold with software that allows the EQ of the transferred audio file to be adjusted. There are also many turntables on the market designed to be plugged into a computer via a USB port for needle dropping purposes.[84]

See also

- Archéophone, used to convert diverse types of cylinder recordings to modern CD media

- Audio signal processing

- Compressed air gramophone

- List of phonograph manufacturers

- Talking Machine World

- Vinyl killer

Notes

- ^ The names record player and turntable have gradually become synonymous, however the second one is more associated with devices requiring separate amplifiers and loudspeakers. Originally, the term turntable referred to the part of phonograph's mechanism providing rotation of the record.[citation needed]

- ^ Historical phonographs could record sound.

References

- ^ "The Incredible Talking Machine". Time. June 23, 2010. Archived from the original on October 14, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- ^ "Tinfoil Phonograph". Rutgers University. Archived from the original on 2011-05-13.

- ^ "History of the Cylinder Phonograph". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2016-08-15.

- ^ "The Biography of Thomas Edison". Gerald Beals. Archived from the original on 2011-09-03.

- ^ "Better Sound from your Phonograph" ISBN 979-8218067304

- ^ "DJ Jargon, DJ Dictionary, DJ Terms, DJ Terminology, DJ Glossary of terms – DJ School UK". Archived from the original on 2019-12-04. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ^ Hockenson, Lauren (20 December 2012). "This Is How a Turntable Really Works". Mashable. Archived from the original on 2019-12-04. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ^ "Application by the Gramophone Company to register "Gramophone" as a trade mark" (PDF). Reports of Patent, Design and Trade Mark Cases. The Illustrated Official Journal. 1910-07-05. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-12.

- ^ "The Edison Diamond Disc Phonograph – History, Identification, Repair". Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ "State Library Victoria – Viewer". Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- ^ "09 Aug 1878 – THE ROYAL SOCIETY. – Trove". Argus. Trove.nla.gov.au. 9 August 1878. Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ "mar 25, 1857 - Phonautograph invented". Time. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Origins of Sound Recording: The Inventors". National Park Service. July 17, 2017. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville". First Sounds. 2008. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Oldest recorded voices sing again". BBC News. March 28, 2008. Archived from the original on April 17, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Villafana, Tana (December 20, 2021). "Observing the Slightest Motion: Using Visual Tools to Preserve Sound". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on January 3, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Schoenherr, Steven E. (1999). "Leon Scott and the Phonautograph". University of San Diego. Archived from the original on February 7, 2018. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "Sound Recording Predates Edison Phonograph". All Things Considered. March 27, 2008. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022 – via NPR.

- ^ "Origins of Sound Recording: The Inventors". www.nps.gov. 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-09-21.

- ^ Fabry, Merrill (May 1, 2018). "What Was the First Sound Ever Recorded by a Machine?". Time. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ Nineeenth-century Scientific Instruments. University of California Press. 1983. p. 137. ISBN 9780520051607. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017.

- ^ Rosen, Jody (March 27, 2008). "Researchers Play Tune Recorded Before Edison". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "The Gramophone". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "L'impression du son", Revue de la BNF, no. 33, Bibliothèque nationale de France, 2009, ISBN 9782717724301, archived from the original on 2015-09-28

- ^ "www.phonozoic.net". Transcription and translation of October 10, 1877 article on Cros "phonographe". Archived from the original on July 24, 2011.

- ^ "www.phonozoic.net". Transcription and translation of December 3, 1877 unsealing of April, 1877 Cros deposit. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011.

- ^ "Charles Cro: French inventor and poet". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2018-03-09. Retrieved 2018-03-09.

- ^ Patrick Feaster, "Speech Acoustics and the Keyboard Telephone: Rethinking Edison's Discovery of the Phonograph Principle," ARSC Journal 38:1 (Spring 2007), 10–43; Oliver Berliner and Patrick Feaster, "Letters to the Editor: Rethinking Edison's Discovery of the Phonograph Principle," ARSC Journal 38:2 (Fall 2007), 226–228.

- ^ Dubey, N. B. (2009). Office Management: Developing Skills for Smooth Functioning. Global India Publications. p. 139. ISBN 9789380228167. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ "Chicago Sunday tribune". Chicago Daily Tribune. 9 May 1877.

- ^ "The Phonograph, 1877 thru 1896". Scientific American. July 25, 1896. Archived from the original on 2009-12-02.

- ^ Klein, Herman (1990). William R. Moran (ed.). Herman Klein and The Gramophone. Amadeus Press. p. 380. ISBN 0-931340-18-7.

- ^ "The Royal Society". The Argus. No. 10, 030. Melbourne, Victoria. 9 August 1878. p. 10. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Article about Edison and the invention of the phonograph". Memory.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2016-08-15.

- ^ University of California. Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project: George W. Washington Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, Department of Special Collections, Donald C. Davidson Library, University of California at Santa Barbara.

- ^ "Experimental Talking Clock" Archived 2007-02-19 at the Wayback Machine recording at Tinfoil.com, URL accessed August 14, 2006

- ^ Aaron Cramer, Tim Fabrizio, and George Paul, "A Dialogue on 'The Oldest Playable Recording,'" ARSC Journal 33:1 (Spring 2002), 77–84; Patrick Feaster and Stephan Puille, "Dialogue on 'The Oldest Playable Recording' (continued), ARSC Journal 33:2 (Fall 2002), 237–242.

- ^ "Very Early Recorded Sound" Archived 2014-02-28 at the Wayback Machine U.S. National Park Service, URL accessed August 14, 2006

- ^ Rosen, Jody (2008-03-27). "Researchers Play Tune Recorded Before Edison". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2011-09-03. Retrieved 2011-10-12.

- ^ Eichler, Jeremy (6 April 2014). "Technology saves echoes of past from silence". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Matthew Rubery, ed. (2011). "Introduction". Audiobooks, Literature, and Sound Studies. Routledge. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-0-415-88352-8.

- ^ Thomas Edison (30 November 1926). "Mary had a little lamb". Archived from the original on 2016-10-03 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Personal Speech To The Future By P. T. Barnum recorded 1890 Archived 2016-03-29 at the Wayback Machine; from archive.org Archived 2013-12-31 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved July 21, 2015

- ^ Othello By Edwin Booth 1890 recorded 1890 Archived 2016-01-16 at the Wayback Machine from archive.org Archived 2013-12-31 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved July 21, 2015

- ^ a b c d e f g h Newville, Leslie J. Development of the Phonograph at Alexander Graham Bell's Volta Laboratory Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine, United States National Museum Bulletin, United States National Museum and the Museum of History and Technology, Washington, D.C., 1959, No. 218, Paper 5, pp.69–79. Retrieved from ProjectGutenberg.org.

- ^ The Washington Herald, October 28, 1937.

- ^ a b Hoffmann, Frank W. & Ferstler, Howard. Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound: Volta Graphophone Company Archived 2017-03-07 at the Wayback Machine, CRC Press, 2005, Vol.1, pg.1167, ISBN 041593835X, ISBN 978-0-415-93835-8

- ^ Schoenherr, Steven. Recording Technology History: Charles Sumner Tainter and the Graphophone Archived 2011-12-23 at the Wayback Machine, originally published at the History Department of, University of San Diego, revised July 6, 2005. Retrieved from University of San Diego History Department website December 19, 2009. Document transferred to a personal website upon Professor Schoenherr's retirement. Retrieved again from homepage.mac.com/oldtownman website July 21, 2010.

- ^ Encyclopedia of World Biography. "Alexander Graham Bell Archived 2010-01-05 at the Wayback Machine", Encyclopedia of World Biography. Thomson Gale. 2004. Retrieved December 20, 2009 from Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ How the Jukebox Got its Groove Archived 2017-01-26 at the Wayback Machine Popular Mechanics, June 6, 2016, retrieved July 3, 2017

- ^ "cylinder history". 16 November 2005. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "the early gramophone". Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ Wallace, Robert (November 17, 1952). "First It Said 'Mary'". LIFE. pp. 87–102. Archived from the original on March 6, 2017.

- ^ Peter A Soderbergh, "Olde Records Price Guide 1900–1947", Wallace–Homestead Book Company, Des Moines, Iowa, 1980, pp.193–194

- ^ The Wall Street Journal, "Phonograph Operated On Transistors to Be Sold by Philco Corp.", June 28, 1955, page 8.

- ^ "TPA-1 M32 R-Player Philco, Philadelphia Stg. Batt. Co.; USA" (in German). Radiomuseum.org. 1955-06-28. Archived from the original on 2013-10-21. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- ^ "The Philco Radio Gallery – 1956". Philcoradio.com. 2012-03-12. Archived from the original on 2013-06-21. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- ^ "/mode/2up "The Only Portable of its Kind!". If (advertisement). November 1961. p. Back cover.

- ^ Billboard, May 21, 1977, page 140

- ^ Trevor Pinch, Karin Bijsterveld, The Oxford Handbook of Sound Studies, page 515, Oxford University Press

- ^ "History of the Record Player Part II: The Rise and Fall". Reverb.com. October 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ a b Six Machines That Changed The Music World, Wired, May 2002

- ^ "What is a cue lever on a turntable? A comprehensive explanation". VintageSonics. 29 March 2023. Archived from the original on 2023-09-06. Retrieved 2023-09-06.

- ^ Rudolf A. Bruil (2004-01-08). "Rabco SL-8E SL-8: Tangential Tonearm, Servo Control, Parallel Tracking, Functioning, Drawings, Construction, Manual". Soundfountain.com. Archived from the original on 2011-10-17. Retrieved 2011-10-12.

- ^ https://www.ortofon.com/media/14912/everything_you_need_to_know_about_styli_types.pdf

- ^ Loescher, Long-Term Durability of Pickup Diamonds and Records, Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, vol 22, issue 10, pp 800

- ^ Digital Needle – A Virtual Gramophone Archived 2003-12-29 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed March 31, 2007

- ^ You Can Play the Record, but Don't Touch Archived 2007-08-12 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed April 25, 2008

- ^ US Patent 3774918

- ^ "Johana.com" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2011-10-12.

- ^ US Patent 3871664

- ^ US Pat. 4105212

- ^ US Pat. 4365325

- ^ a b "Vinylengine.com". Vinylengine.com. 2009-11-09. Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2011-10-12.

- ^ US Patent 4521877

- ^ US Patent 4855989

- ^ Barton, F.C. (1932 [1931]). Victrolac Motion Picture Records. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, April 1932 18(4):452–460 (accessed at archive.org on 5 August 2011)

- ^ Powell, James R., Jr. and Randall G. Stehle. Playback Equalizer Settings for 78 rpm Recordings. Third Edition. 1993, 2002, 2007, Gramophone Adventures, Portage MI. ISBN 0-9634921-3-6

- ^ Martens, Todd (11 June 2009). "Vinyl sales to hit another high point in 2009". Los Angeles Times Music Blog. Archived from the original on 26 April 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ^ McIntyre, Hugh. "Vinyl Sales Grew More Than 50% In 2014". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2017-07-29.

- ^ Team, V. F. (2018-02-20). "Turntable sales fell in 2017 despite rising record sales". The Vinyl Factory. Archived from the original on 2019-05-05. Retrieved 2019-05-05.

- ^ Drenon, Brandon (13 March 2023). "Vinyl records outsell CDs for first time in decades". BBC News. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ "Vinyl to USB Conversion". recordplayerreviews.org. Archived from the original on 2016-07-30.

- ^ "USB turntable comparison". Knowzy.com. 2008-12-01. Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2011-10-12.

Further reading

- Bruil, Rudolf A. (January 8, 2004). "Linear Tonearms." Retrieved on July 25, 2011.

- Gelatt, Roland. The Fabulous Phonograph, 1877–1977. Second rev. ed., [being also the] First Collier Books ed., in series, Sounds of the Century. New York: Collier, 1977. 349 p., ill. ISBN 0-02-032680-7

- Heumann, Michael. "Metal Machine Music: The Phonograph's Voice and the Transformation of Writing." eContact! 14.3 — Turntablism (January 2013). Montréal: CEC.

- Koenigsberg, Allen. The Patent History of the Phonograph, 1877–1912. APM Press, 1991.

- Reddie, Lovell N. (1908). "The Gramophone And The Mechanical Recording And Reproduction Of Musical Sounds". Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution: 209–231. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- Various. "Turntable [wiki]: Bibliography." eContact! 14.3 — Turntablism (January 2013). Montréal: CEC.

- Weissenbrunner, Karin. "Experimental Turntablism: Historical overview of experiments with record players / records — or Scratches from Second-Hand Technology." eContact! 14.3 — Turntablism (January 2013). Montréal: CEC.

- Carson, B. H.; Burt, A. D.; Reiskind, and H. I., "A Record Changer And Record Of Complementary Design", RCA Review, June 1949

External links

- c.1915 Swiss hot-air engined gramophone at Museum of Retro Technology

- Interactive sculpture delivers tactile soundwave experience Archived 2021-03-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Very early recordings from around the world

- The Birth of the Recording Industry

- The Cylinder Archive

- The Berliner Sound and Image Archive

- Cylinder Preservation & Digitization Project – Over 6,000 cylinder recordings held by the Department of Special Collections, University of California, Santa Barbara, free for download or streamed online.

- Cylinder players held at the British Library Archived 2012-02-06 at the Wayback Machine – information and high-quality images.

- History of Recorded Sound: Phonographs and Records

- EnjoytheMusic.com – Excerpts from the book Hi-Fi All-New 1958 Edition

- Listen to early recordings on the Edison Phonograph

- Mario Frazzetto's Phonograph and Gramophone Gallery.

- Say What? – Essay on phonograph technology and intellectual property law

- Vinyl Engine – Information, images, articles and reviews from around the world

- The Analogue Dept – Information, images and tutorials; strongly focused on Thorens brand

- 45 rpm player and changer at work on YouTube

- Historic video footage of Edison operating his original tinfoil phonograph

- Turntable History on Enjoy the Music.com

- 2-point and Arc Protractor generators on AlignmentProtractor.com