Contents

-

(Top)

-

1Background

-

2Course of the protests

-

3Aftermath

-

4See also

-

5Notes

-

6References

-

7Sources

-

8Further reading

-

9External links

The Savannah Protest Movement was an American campaign led by civil rights activists to bring an end to the system of racial segregation in Savannah, Georgia. The movement began in 1960 and ended in 1963.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, African Americans in Savannah were subject to Jim Crow laws that enforced a strict system of racial segregation whereby they were not allowed to use many of the same facilities used by white people. However, African Americans attempted to push back against this system, and by the 1940s, the NAACP, under the leadership of Ralph Mark Gilbert, organized voter registration drives among the black population and negotiated agreements with moderate city officials to secure certain improvements for the community, including the hiring of African American police officers and greater investment in infrastructure, such as road repairs and the creation of a new high school. By the early 1960s, W. W. Law had become the president of the local NAACP chapter, with Hosea Williams serving as vice president and head of the local youth council.

On March 16, 1960, the movement began with a series of sit-ins conducted by several dozen student activists at segregated lunch counters throughout downtown Savannah, resulting in the arrest of three protestors at Levy's Department Store. Over the next several months, protestors continued to target segregated facilities with sit-in related protests, in addition to marches, pickets, and other forms of direct action. Additionally, Williams organized the Chatham County Crusade for Voters to mobilize the city's black voting bloc to push for change from the city government. By October 1961, a partial agreement was reached to desegregate some facilities in the city, though protesting continued to achieve complete desegregation. By mid-1963, Williams, who by this time had become affiliated with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), began to hold nighttime marches that saw hundreds of arrests and an instance of rioting that resulted in the burning of at least one building and the mobilization of the Georgia National Guard. Following this, white businessmen in the city agreed to a full desegregation of the city and the city government, under Mayor Malcolm Roderick Maclean, agreed to rescind all remaining segregation ordinances. This officially came into effect on October 1, bringing an end to the movement.

The Savannah movement is notable among protests of the civil rights movement for its length, its achievement of full desegregation, and for the general lack of violence when compared to other movements, such as the Birmingham campaign. Following the movement, Williams left Savannah to become a member of the SCLC national board, where he led a nationwide voter registration program during the 1960s. Meanwhile, in Savannah, Law served as NAACP local president until retiring in 1976. In 2016, the Georgia Historical Society installed a Georgia historical marker to commemorate the protest movement at the site of the former Levy's Department Store.

Background

Early history of Savannah, Georgia

The city of Savannah, Georgia, was founded in 1733,[1] making it the oldest city in the state and one of the oldest in the United States.[2][3] At its founding, the city was a farming community where slavery was banned, though the institution became legal in 1750 and, in the following years, Savannah became a major port city in the Atlantic slave trade.[1] During the American Civil War, the city was captured by General William Tecumseh Sherman in December 1864 at the conclusion of his March to the Sea,[1] leaving the city relatively undamaged.[2] The following month, while still in the city, Sherman issued Special Field Orders No. 15, which gave newly freed black people confiscated land from plantations, though these orders were reversed later that year by President Andrew Johnson.[1] In the latter half of the 19th century, after the Reconstruction era,[4] African Americans in the Southern United States faced economic and political persecution and discrimination under a system of laws known as Jim Crow laws.[1]

Developments during the late 19th and early 20th century

In Savannah, one of the earliest examples of organized opposition to racial discrimination in the post-Reconstruction era came in the 1890s, when a boycott prevented the city's buses from becoming racially segregated.[5] The city's public transit would remain one of the only racially integrated systems in the region until they became segregated in 1907.[5] By the early 1900s, Savannah boasted numerous African American businesses, including seven banks,[1] with the city's black community centered on West Broad Street, near Savannah Union Station.[6] Additionally, several chapters of national African American organizations were founded prior to the end of World War I, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), whose offices were on West Broad Street,[7] the National Negro Business League, and the National Urban League.[5][1] This coincided with a statewide growth in these organizations, which established chapters in other Georgia cities, such as Albany, Atlanta, and Augusta.[5] However, during the Interwar period, violent opposition from white Americans, including multiple lynchings, as well as the Great Depression, seriously hurt these organizations' efforts and led to the closure of many local chapters.[8][1] By the 1930s, organized protest against discrimination in the state occurred almost exclusively in either Atlanta or Savannah,[9] and by 1940, according to historian Mark Newman, the NAACP in Georgia was "moribund".[10] The previous year, the charter for the Savannah NAACP chapter had been revoked due to a precipitous decline in membership.[11]

Impact of World War II

The Great Depression and, later, the United States's involvement in World War II contributed to the migration of approximately 1 million African Americans from rural areas to the urban centers of the American South, such as Atlanta and Savannah,[12] and by 1940, one-third of the 1 million African Americans in Georgia lived in municipalities with populations greater than 5,000.[13] The war contributed to a surge in employment for African Americans, with many in Savannah finding employment in the war effort and in the city's shipyard.[14] Across the Southern United States, black Americans gained 1 million new jobs during the war.[14] By 1946, Savannah had over 100 black-owned businesses and a growing black middle class, which contributed to a new, developing opposition to discrimination.[15] According to historian Stephen Tuck, "The emergence of small pockets of relatively prosperous black Georgians in cities, therefore, provided the environment from which civil rights leadership could spring".[16] Also during the war, over 100,000 black men were stationed in several military bases in the state.[17] In several bases, such as Camp Gordon near Augusta, Fort Benning near Columbus, and Camp Stewart near Savannah, these African American enlisted men became involved in several instances of militant opposition to discrimination, including a mutiny of black soldiers at Camp Stewart caused primarily by poor living conditions.[17] These acts were, according to Tuck, some of the first acts of militant opposition to discrimination witnessed by African Americans in the state, and following the war, many black veterans became active participants in further anti-discrimination protests.[18]

Reinvigorated efforts for civil rights

During the 1940s, several political developments occurred in Georgia at the state level that increased African Americans' electoral opportunities.[19] First, in 1943, the voting age was reduced from 21 to 18.[20] Then, in 1944, the state's white primary system was abolished.[19] Finally, in 1945, the poll tax was ended.[21] Some of these electoral reforms were implemented by Georgia Governor Ellis Arnall, a political moderate who had beaten incumbent Eugene Talmadge in the 1942 election thanks to support from white liberals.[14] Around this same time, activists in the state, especially consisting of black women, began to organize voter registration drives and pushed for the election of moderate politicians at the local level.[21] Black civic leaders would then negotiate with these elected officials and were able to obtain concessions and agreements that included increased funding for public black schools and having black jurors on court cases.[21] Between 1940 and 1946, the number of African Americans registered to vote in the state rose from roughly 20,000 in 1940 to 135,000 in 1946.[22] Voter registration drives were especially successful in the three largest cities in the state: Atlanta, Savannah, and Augusta.[22]

NAACP under Ralph Mark Gilbert

In Savannah, the state's second-largest city,[23] African American activists began voter registration drives as early as 1941.[24] In April 1942, the NAACP branch in Savannah was rechartered with about 300 members.[25] That same year, Ralph Mark Gilbert, the pastor at First African Baptist Church, one of the oldest black churches in the United States,[26] became president of the Savannah NAACP and led efforts to revive the organization.[27][28] Under his leadership, the chapter grew to a membership of 3,000 people,[29] a figure that surprised many NAACP officials, such as Ella Baker.[25] Additionally, the branch recruited many younger members and, according to The Crisis magazine, had the largest youth organization in the country by 1943.[30] From 1942 to 1948, Gilbert also served as the president of the Georgia NAACP organization,[31] during which time he oversaw the creation of 50 new NAACP local chapters in the state.[10] By 1946, the NAACP had 13,595 members in the state, up from under 1,000 before Gilbert's presidency.[32]

Working with his wife Eloria,[33] Gilbert organized youth volunteers to spearhead mass voter registration drives in Savannah.[31] By 1946, about half of Savannah's 45,000 African Americans were registered to vote,[34] and throughout the decade, Savannah boasted both the highest percentage of African Americans registered to vote and the highest percentage of African Americans in the NAACP in the American South.[30] The creation of this large voting bloc allowed African Americans in Savannah to negotiate certain agreements with city officials that led to the creation of a new high school, recreation center, and swimming pool for the community, as well as road improvements and the hiring of two black jail matrons.[34] Also, according to a report from the Southern Regional Council, the registration drive had resulted in the election of a "very liberal judge" that resulted in black Savannahians "getting some very sound decisions from the court".[34] Savannah was also the first city in Georgia to create a black advisory committee for its mayor, establishing a line of communication between the city government and the black community.[35] Possibly most significant was the hiring of nine African American police officers,[34] which, along with hirings around the same time made by the Atlanta Police Department, constituted the first instatements of black policemen in the American South since the Reconstruction era.[21]

In addition to electoral methods, Gilbert also oversaw several instances of direct action to combat segregation in the city.[34] Gilbert threatened a protest against the management of an all-African American public housing project that resulted in the hiring of several black supervisors, and he led the NAACP in a boycott against a store where the white owner had beaten a black woman.[34] Also under his presidency, there was a demonstration by about 50 students from Georgia State College where they boarded a bus and refused to relinquish their seats to white patrons, leading to their arrests.[34] Gilbert also led the drive to establish a YMCA on West Broad Street in the 1940s[31] After the war, the chapter under his leadership supported the Congress of Industrial Organizations's Operation Dixie, which aimed to unionize African American workers at the city's shipyard.[36]

Continued challenges to civil rights

Despite the progress in Savannah, which Gilbert called "the most liberal city in the state",[37] African Americans in the state still faced discrimination and violence.[32] For example, in 1946, four African Americans near the city of Monroe were killed in an act of mob violence known as the Moore's Ford lynchings, and in 1948, members of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) waged a terrorist campaign against African Americans during that year's gubernatorial election.[32] Similar instances of KKK violence occurred in the 1946 election, spurred by candidate and former Governor Talmadge, who used a little-known provision in the Official Code of Georgia Annotated to effectively disenfranchise many African Americans.[38][note 1] Savannah was still also a segregated city,[2][39] as evidenced in 1948 when the Freedom Train, a nationwide tour that displayed the original United States Declaration of Independence and United States Constitution in several cities across the country, set up segregated viewing lines in Savannah, which were decried by the NAACP Youth Council as a "shameful disgrace".[6] By 1960, the black unemployment rate in Savannah was about twice that of the white community, and the median income for a black person was about one-third of that for a white person.[40]

Civil rights movement in Savannah

Gilbert served as the president of the Savannah NAACP chapter until 1950,[31] when he was succeeded by W. W. Law,[41][42] who, earlier that year, had become a member of the NAACP national board of directors.[2] Law was a mentee of Gilbert's who had served on the NAACP Youth Council while in high school, during which time he served as the group's first president.[30] As part of the youth council, he participated in activism such as protests against the segregation of Grayson Stadium.[42] As a civil rights activist, Law was a believer in nonviolent resistance as an effective means to achieve social change,[42] and he advocated against more violent tactics.[41] In 1942, he enrolled at Georgia State College in Savannah, though he was drafted into military service after his first year.[42] He later re-enrolled under the provisions of the G.I. Bill and graduated with a degree in biology, after which he found employment with the United States Post Office Department as a mail carrier.[42] This job helped him in his work with the NAACP, as it kept him in close contact with people throughout the city.[7][43] In a bit of a departure from Gilbert, Law focused primarily on continuing to maintain the local Savannah chapter and focused less on statewide activism and chapter-building.[44]

Around the same time, Hosea Williams became another noted civil rights activist in Savannah.[2] Williams was a graduate of Morris Brown College and Atlanta University, both in Atlanta, and had moved to Savannah in the 1950s to work as a chemist for the United States Department of Agriculture at Savannah State College.[45][46][47] Williams believed that his hiring had been an example of tokenism, and this, coupled with an experience where one of his children was denied service at a lunch counter in the city, spurred him to become an activist for civil rights.[47] By the early 1960s, he had become the vice president of the Savannah NAACP chapter under Law,[45] and additionally, headed the local Youth Council.[39] Another noted civil rights leader during this time was Eugene Gadsden,[48][49] who served as the NAACP local chapter's legal counsel.[42]

Sit-in movement

Under Law's administration, the NAACP chapter in Savannah continued to grow, with historian Clare Russell stating that this was due in part to "the lack of overt racial violence which meant that they could organize in relatively security".[50] By 1959, Law began to promote more direct action to combat segregation.[2] Starting in March 1960, the local NAACP chapter began to sponsor weekly meetings at local black churches to keep their members informed about ongoings in the broader civil rights movement.[51] Around this time, many young activists in the city were interested in replicating the Greensboro sit-ins,[3] a nonviolent protest that had begun in Greensboro, North Carolina, the previous month.[48][51][52] As part of the protest, African American activists would go to segregated lunch counters and sit down at them, refusing to leave until they were either served, thrown out, or arrested.[2] These initial protests in Greensboro sparked the larger sit-in movement that saw activists in many cities throughout the American South employ similar nonviolent practices to integrate segregated spaces, such as lunch counters, stores, and public facilities.[48]

Course of the protests

1960

First sit-ins

The sit-in movement came to Savannah on March 16, 1960,[49][51] when several black student activists, led by the NAACP Youth Council,[54] first gathered at First African Baptist before leaving to downtown Savannah,[29] where they performed sit-ins at eight businesses.[55][56][57] In addition to the sit-ins, about 80 student protestors led a march through the streets to protest segregation.[58] At the Azalea Room, a lunch counter inside the Levy's Department Store,[49][29] Carolyn Quilloin, Joan Tyson, and Ernest Robinson were arrested after they continued to try to order after the owner demanded that they leave.[29][48] In jail, the arrested proceeded to sing "We Shall Overcome".[48] At the time of the sit-ins, Robinson had written part of Psalm 23 on his palm, and in a later interview with the Savannah Morning News, Coleman stated, "That verse uplifted us. We were very familiar with what had happened to Emmett Till, a 14-year-old student who was killed in Mississippi for allegedly whistling at a White girl across the street. While we thought that we were safe in Savannah, we knew that anything could happen".[48] These three students, all members of the NAACP Youth Council, were convicted under an anti-trespassing state law and sentenced to either five months in jail or a $100 fine (equivalent to $916 in 2021).[29] In addition to Levy's Department Store, other restaurants targeted by the sit-ins included Anton's Restaurant, franchises of Krystal and Morrison's Cafeteria, and the lunch counters inside of the downtown Woolworth's and S. H. Kress & Co.[39][53][42] Alongside the Atlanta sit-ins, which began one day earlier,[59] these marked some of the first sit-ins in the state.[60]

Boycott and further protests

On the same day as the sit-ins, the local NAACP announced a boycott of downtown stores.[61] Black civic leaders announced that the boycotts would target segregated businesses and would continue until these businesses were desegregated.[56] In addition to this, they also demanded the hiring of black workers at levels above menial positions, the desegregation of public drinking fountains and restrooms, and the use of courtesy titles, such as Mr., Mrs., and Miss, instead of simply "boy" or "girl",[55] when referring to African Americans.[56] On March 17, the boycott was temporarily placed on hold as Law and several other activists in Savannah traveled to Sylvania to participate in a hearing of the Sibley Commission,[62][note 2] but on March 20, the first mass meeting of the protest movement was held at Bolton Street Baptist Church on West Broad Street.[64] Members at the meeting voted unanimously to officially institute a boycott against downtown businesses,[65] and Law, speaking to an audience of about 1,000 people, stated that the boycotts would continue until integration was achieved.[28] Local churches would serve as regular meeting spots for the duration of the protest,[65] commonly held at either Bolton Street Baptist or St. Philip AME Church.[42]

On March 26, Levy's Department Store became the first store in downtown to be the target of a concerted protest action that saw picketing outside the building,[59][29][note 3] with signs bearing slogans such as "You can buy a $50 suit, but not a 10 cent cup of coffee" and "We want a mouthful of freedom".[51] Over the next several weeks, 23 more protestors would be arrested.[59] In April, the city council passed an ordinance banning protesting in front of businesses by two or more people,[66] with a reporter for Time quoting Savannah Mayor Lee Mingledorff Jr. as saying, "I don't care whether [the ordinance is] especially constitutional or not".[67] That same month, black marchers in that year's Easter parade wore clothing from last year's march, refusing to patronize downtown stores.[66] By May, the Pittsburgh Courier listed Savannah as "one of the three hot spots of the student movement in the South", alongside Biloxi, Mississippi and Jacksonville, Florida.[68]

Other forms of sit-in protests

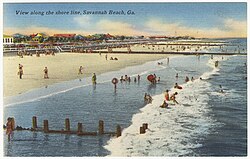

By August, protesting in Savannah had spread from sit-ins to other nonviolent direct action.[65] On August 17, protestors at the beach on nearby Tybee Island conducted a "wade-in", inspired by a similar protest that had taken place in Biloxi,[57] where they waded into the water on the segregated beach.[65] Protestors, which included student activist Benjamin Van Clarke[note 4] and future Georgia House of Representatives member Edna Jackson,[69][70] swam for about 90 minutes before police put an end to the protest and arrested 11 people.[65]

On August 21, student activists affiliated with the NAACP conducted the city's first "kneel-ins", modeled after similar events in Atlanta,[57] when they visited ten white churches.[71] About a week prior to this church desegregation effort, a pastor at a local Methodist church had written an open letter denouncing the planned protests, drawing national media attention.[72] In total, five churches turned away the protestors, three, including the Lutheran Church of the Ascension, offered to allow them to attend the services in segregated seating, while two, Christ Church and Tabernacle Baptist Church, allowed them to attend the service in integrated seating.[73] The following Sunday, protestors again conducted "kneel-ins", which saw six churches turning them away and five letting them attend.[73]

By October, activists had participated in numerous forms of protest against segregated facilities, including "wade-ins", "kneel-ins", "ride-ins" in segregated buses, and "stand-ins" at segregated movie theaters, among others.[66][56] In one instance that activists later referred to as a "piss-in",[66][56] activist Judson Ford was arrested for unknowingly using a segregated public restroom.[57] At Daffin Park, near Grayson Stadium, six black youth were arrested for breach of the peace after they were caught playing basketball in the whites-only park.[66] A lawsuit that rose to the Supreme Court of the United States eventually overturned the charges against the kids, which carried a fine of $100 ($916 in 2021) and five months in prison,[56] as they were ruled unconstitutional.[66]

Voter registration drive

In addition to the boycott, black civic leaders began a massive voter registration drive to mobilize black eligible voters in Chatham County.[54][49] To achieve this, Williams organized the Chatham County Crusade for Voters (CCCV),[74] an organization that was structurally independent of, but still received support from,[75] the NAACP.[70] The CCCV, which Tuck described as the "political arm" of the local NAACP,[76] was directly led by Williams.[77] By the end of 1960, thanks in large part to the CCCV's efforts, 57 percent of the eligible black citizens of Savannah were registered to vote, a higher percentage than among the city's white population.[7][43] In Savannah, a city with a population of about 150,000 where roughly one-third of the population was black, this gave the black voting bloc a great deal of political strength.[78] This political mobilization coincided with the elevation of Malcolm Roderick Maclean, a city alderman, to the position of mayor to fill a vacancy in the office.[79] Maclean worked with the black community on several agreements, such as the appointment of one black person to each city council board.[43][67]

1961

In late March 1961, students at Johnson High School initiated a boycott of classes after the school board announced that they would not be renewing the employment contract for Principal E. C. Cheatham.[70] This boycott, led by Van Clarke,[70] divided the leadership of the protest movement.[81] From the beginning, Gadsden was opposed to the boycott, fearing that it would hurt the NAACP's broader goals for school integration.[81] In Savannah, despite the ruling in Brown v. Board of Education stating that school segregation was unconstitutional, the public school system remained racially segregated.[2] Meanwhile, in the beginning, both Law and Williams supported the boycott, with both participating in a rally in support of the student movement on March 23.[81] However, by July, Law was seeking a way to quietly end the boycott.[81]

As opposed to Law, Williams continued to support the boycott and saw potential in Van Clarke as a civil rights activist, inviting him to attend a workshop at the Dorchester Academy in nearby Liberty County that was run by activist Septima Poinsette Clark.[81] Modeled after the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee,[82] the Dorchester Academy was one of a number of "Citizenship Schools" established throughout the Southern United States with the goal of training civil rights activists and giving African American adults lessons in civics that would help them to navigate the obstacles they faced in exercising their political rights.[80][52] Many of the students at these schools were middle-aged and offered financial support for the younger protestors.[52] Van Clarke would later serve as the head of the CCCV's youth division and organized as many as three marches per day, including one where protestors dressed in black and carried a casket in a mock funeral for segregation.[7] Throughout the protests, Van Clarke would be arrested 25 times.[7]

In June 1961, with the boycott against downtown stores still in place, Savannah's bus company announced their commitment to hire black drivers.[66] The agreement with the bus company represented a major breakthrough for the activists and demonstrated that the protest was having an effect on local businesses.[56] Since the boycott began the previous year, five businesses had declared bankruptcy, at least partially due to the effects of the protest.[66][67][56] According to the local chamber of commerce, the boycott had contributed to a 15 percent decrease in revenue for downtown businesses as a whole.[83] On the other side of the protests, segregationists began a counter-boycott of stores that had already desegregated,[84] and protestors continued to face the threat of physical violence, as evidenced by a March 15 report in The Atlanta Constitution about an activist who was assaulted by a group of white youths during a sit-in at Woolworth's.[85] Also, in July 1961,[86] Law was fired from his job with the postal service due to his civil rights activism, though he was reinstated following pushback against his termination from national NAACP leaders and United States President John F. Kennedy.[42][41]

Partial desegregation agreement

By late 1961, merchants in downtown Savannah had pushed the city government to negotiate directly with the protest leaders to bring an end to the boycotting.[56] Mayor Maclean assembled a biracial committee that agreed to several of the protestors' demands, including a commitment to hire black people to higher ranking positions and the use of courtesy titles.[76] Additionally, the city government revoked an ordinance mandating segregated lunch counters and also desegregated many public facilities, including buses, golf courses, movie theaters, and restaurants.[54][56][66] This agreement was reached on October 1,[49] and following this, the targeted boycott against downtown businesses came to an end.[54][76] However, targeted protests still continued against institutions in the city that remained segregated,[66] such as parks, restaurants at the local airport and train station, and the Savannah Fire Department.[76] In December of that year, the Central of Georgia Railway's Nancy Hanks passenger train was desegregated, with a group of black people riding in the white passenger section on the train's route from Savannah to Atlanta.[66]

Rivalry between Law and Williams

Since 1960, there had a developing rivalry between Law and Williams.[74] This primarily stemmed from Williams's general dissatisfaction with the NAACP leadership's advocacy for more legislative means of achieving civil rights as opposed to more direct forms of protest.[74] Williams, meanwhile, was more in favor of using direct action,[42] as throughout the protests, Williams organized many large marches and rallied, including a lie-in at Morrison's Cafeteria and rallies at Johnson Square.[7] Additionally, during his lunch breaks, Williams would often give speeches from atop a boulder monument to Tomochichi at Wright Square, in front of the city's federal courthouse.[7]

By 1962, the strife between Law and Williams had escalated, driven in part by the NAACP's eventual condemnation of Van Clarke's boycott at Johnson High School, which Williams continued to support.[75] Around October of that year,[87] the rivalry reached a fever pitch when Law refused to support Williams's bid to join the national board of the NAACP.[75] Williams was hurt by the refusal, later saying, "It was kind of like telling a man, 'You don't have your own family. Your family won't vote for you'".[75] Following this, Williams began to pivot away from the NAACP and towards the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).[75] The SCLC, which was led by activist Martin Luther King Jr., was the group responsible for funding the citizenship schools,[75] including the Dorchester Academy led by Clark.[81][80] This division ultimately forced many activists in Savannah to pick between Williams and Law,[75][42] especially when the CCCV became affiliated with the SCLC that year.[58]

1963

Night marches

Through 1963, Williams continued to work closely with the SCLC,[75] eventually joining the organization's national board.[74][88] In April of that year, he took a brief break from activism in Savannah to bring activists from that city to Alabama to help King in his Birmingham campaign.[74] However, on June 4,[76] Savannah's movie theaters resegregated following public pressure from the city's white community,[56][76] prompting renewed activism in the city.[66] Led primarily by Williams, activists held large marches along Broughton Street during both the day and at night.[89] Williams felt that the night marches would bring national attention to the protest, while Law believed that the night marches would provoke violence that would ultimately hurt the protest.[58] Many other church leaders were opposed to the marches and refused to allow Williams to use their churches for organizing.[90] Despite this, Williams led groups of up to 1,000 protestors on these night marches.[58] These marches were part of a nationwide series of renewed civil rights protest in 1963.[91][76]

Within one week of the marches beginning, about 500 protestors were arrested,[58] and as violence escalated, Williams asked the SCLC to send protest organizers James Bevel, Dorothy Cotton, and Andrew Young to Savannah to teach the protestors more nonviolent tactics.[92] In one march, these organizers led a group of 200 children that ended in all marchers being jailed.[92] On June 12, the Savannah Youth Strategy Committee, a local affiliate of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) that was led by Van Clarke, began protesting against the city after Mayor Maclean failed to follow through on the group's demands to immediately desegregate all public facilities and agree to not arrest activists that were protesting against segregated private facilities.[93] On June 19, a group of about 3,000 protestors held a mass prayer outside of a segregated Holiday Inn that resulted in 400 arrests.[94] After this, the remaining activists, led by Williams and Van Clarke, gathered outside the local jail to protest the arrests, during which time city and state law enforcement officers used tear gas to disperse the crowds.[94] Several days later, on June 25, Van Clarke was arrested for a third time since the start of the protest movement and, per the terms of a 1960 state trespassing law, was held without bail.[95] He was later ordered to either pay a $1,500 fine ($13,277 in 2021) or serve two years in jail.[95]

Williams's arrest and subsequent rioting

On July 8, Williams was arrested and held on bail for $7,500 ($66,383 in 2021).[95][note 5] Following his arrest, Bevel, Cotton, and Young took charge of the protests.[92] Ultimately, Williams spent over a month in jail.[note 6] On July 10,[note 7] a riot broke out between police officers and about 2,000 protestors who had gathered outside the city jail following the arrest of SNCC Field Secretary Bruce Gordon.[96] During the two-hour fight, police used tear gas and high-powered water hoses to disperse the crowds and beat several protestors with clubs, leading to multiple injuries.[96][92] The riot resulted in at least one store being burned and saw 75 peopple arrested.[56][66] Following this, the Georgia National Guard became mobilized,[92][89][56] with Governor Carl Sanders promising to take "whatever steps necessary" to bring an end to the protests.[96] Additionally, the city government banned marches.[89][56]

Desegregation agreement reached

Following the rioting, several white business owners in the city intervened on behalf of the protestors and helped to secure his[clarification needed] release from jail.[46] Additionally, many businesspeople in the city agreed to negotiate an end to the protests.[92] By this point, the protests had led to a 30 percent total decline in trade in the city.[98] A group of 100 city businessmen,[45][1] assembled by Mayor Maclean,[75] met and created a plan that would see the desegregation of the city's remaining public and private facilities in exchange for a 60-day suspension of protesting.[99] In addition, the city government would fully rescind all remaining segregation ordinances.[54][49] This agreement was implemented in August, prompting the NAACP to call off a planned Christmas boycott.[7][56] On October 1,[97][52][100] this desegregation came into effect, affecting, among other institutions, all of the city's bowling alleys, hotels, motels, movie theaters, and swimming pools.[92][55] The desegregation was so thorough that, during an address given on New Year's Day 1964 at the city's Municipal Auditorium,[43] King praised Savannah as "the most desegregated city south of the Mason–Dixon line".[7][97][101]

Aftermath

Analysis by historians

Many historians have noted the uniqueness of the Savannah protest movement for its longevity and overall success.[52][102][49] In a 2019 article, the Georgia Historical Society stated, "Although a part of the larger Civil Rights Movement, the Savannah Protest Movement was uncommon, especially in its ability to exert continuous pressure on white power structures over an extended period".[52] Historian Elizabeth Ellis Miller, discussing the protest movement in 2023, said, "Savannah ... became known as a site for peaceful demonstrations and a model for other locales considering taking on sit-ins".[102] Many notable civil rights activists saw their first involvement in the national movement in Savannah, including Van Clarke and Earl Shinhoster,[103] and Williams called the 1963 protests the nation's largest outside of Birmingham.[104] The protest is also notable for the level of peace maintained throughout the movement, as opposed to the extreme levels of violence seen in civil rights movements in other cities throughout the American South during this time.[2]

Because of the sit-ins, Savannah became the first city in Georgia with desegregated lunch counters,[45][46] with Tuck considering the "kneel-ins" and "wade-ins" in Savannah to have been more successful than those in Atlanta and Biloxi, respectively.[57] In that same vein, Tuck stated in a 2001 book that "though Atlanta was Georgia's leading city, Savannah was, in many ways, the leading city of protest".[105] Considering the differences between Atlanta and Savannah, Tuck claims that the differences between Atlanta and Savannah during the civil rights movement stemmed primarily from the approaches taken by the local leadership,[106] stating that, "the cautious attitude of Atlanta's black community leaders ... led to a protest that lacked the vibrancy and vision of the movement in Savannah".[107] Discussing the two cities in a 1998 book, historian Jeff Roche states that, while black civic leaders in Atlanta had a history of direct communication with white city leaders, Savannah lacked this history, leading to a more powerful and active civil rights movement led by the local NAACP chapter.[108]

According to Tuck, part of the success of the Savannah movement stemmed from Savannah's relatively liberal political climate compared to other cities in the state.[40] Tuck argues that the city "displayed the racial discrimination and double standards characteristic of the "Old South" without the overwhelming bitterness and proclivity to violence associated with the "Deep South" ".[109] Ultimately, however, he credits the role that black leadership played in the protest movement as the primary cause for its success,[25] as the protest was almost entirely led by local leaders.[110] To this end, several sources have noted that local leadership turned down an offer by King to come to Savannah to participate in the protest, believing that the movement was making good progress without him.[68][111][56]

School integration

According to Tuck, the only goal not fully achieved by the protestors during the movement was the integration of the city's schools, as the city followed many Southern cities in slowly integrating their school system.[67] In 1962, Law, L. Scott Stell (chair of the NAACP's education board), and, several dozens black families filed a lawsuit against the city of Savannah in an attempt to force them to integrate.[2][42] In September 1963, as part of school integration, several black students enrolled in two formerly all-white high schools in the county.[7][56][112] School integration was not addressed in the October 1, 1963, agreement that had brought an end to the protests,[2] and it would take later litigation to fully end this segregation.[1] Savannah's public schools were ordered to fully integrate in 1964.[42]

Later history

Following the end of the protests, Williams became more involved in the SCLC and, thanks in large part to his success with CCCV, became the director of the organization's voter registration efforts in 1964.[46] In October of that year, he moved to Atlanta, bringing with him several of his allies from Savannah, including Van Clarke.[90] Without Williams's presence in the city, Law and the NAACP returned to their position of prominence within the city's African American civic leadership.[90] The NAACP established a new political group that began to supersede the CCCV,[113] and two years later, the group received funding from the Voter Education Project, much to Williams's chagrin.[114] Meanwhile, Williams headed the SCLC's SCOPE Project, a voter registration drive that saw mixed success in the 1960s, primarily hindered by mismanagement and accusations of impropriety against Williams.[115] He later served as a field director for the Poor People's Campaign and was the executive director of the SCLC from 1969 to 1979.[116] Law would serve as the local NAACP president until 1976, when he retired.[53][42] Around this time, he became an advocate for the preservation of African American history,[42][31] and in this capacity, he was influential in the eventual creation of the Ralph Mark Gilbert Civil Rights Museum in what was, at the time of the protests, the headquarters for the NAACP chapter.[64][100] By 1991, African Americans made up over half of the city's population of about 140,000,[1] and several years later, in 1995, the city elected its first black mayor.[31]

By 1998, the building that had housed the Levy's Department Store where the initial three arrests were made in 1960, was vacant.[29] However, by 2016, the building had been purchased by the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) and had been repurposed for use as the college's Jen Library.[54] On September 23, 2016, the Georgia Historical Society erected a Georgia historical marker near the building to commemorate the protest movement.[54] The marker was part of the society's Civil Rights Trail, which is a series of markers intended to highlight important events and locations in the civil rights movement in Georgia.[49] Prior to the marker's dedication, SCAD hosted a celebration that included numerous guests who had participated in the protest movement, including Quilloin and Tyson.[49]

See also

Notes

- ^ According to historian Jeff Roche, the provision "allowed any citizen of the state to challenge the voting qualifications of another based on citizenship, residency, character, literacy, or interpretation of the United States Constitution". It was then the responsibility of the challenged individual to prove that they were qualified to vote. Talmadge published a standard challenge form in an April 1946 edition of his newspaper, the Statesman, and focused disenfranchisement efforts in counties that had seen significant African American voter registration. According to Roche, the disenfranchisement efforts, as well as intimidation and violence against black voters, allowed Talmadge to win in several counties with a margin of victory that was less than the number of disenfranchised black voters. Talmadge's main opponent in the election, the comparatively progressive James V. Carmichael, lost the election despite carrying about 98 percent of the black vote.[38]

- ^ The Sibley Commission was a state-led commission that sought out public input on how to approach the issue of school integration.[62] The commission was originally going to hold a meeting in Savannah, but changed the location to Sylvania,[63] possibly due to the actions of the local NAACP.[61]

- ^ In a 1998 book, historian Jeff Roche stated that the boycotting of downtown businesses began on March 16, 1960.[61] A different start date for the boycotting of March 26 is given in a 1998 book by historian Townsend Davis.[29] However, Roche states that March 26 marked the beginning of picketing activities.[59]

- ^ Spelled "Van Clark" in some sources.[7]

- ^ A 2014 book by historians Christopher M. Richardson and Ralph Luker states that Williams's bail was set at $100,000.[92] The value given in this article of $7,500 comes from a 1963 report by the United States House Committee on the Judiciary.[95]

- ^ Sources differ on the length of time Williams spent in jail, with values of 34 days[75] and 65 days.[66][56]

- ^ The date of July 10 is given in a 1963 report by the United States House Committee on the Judiciary.[96] However, a 2014 book by Christopher M. Robinson and Ralph Luker gives a date of July 11.[92]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gottlieb 1991, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Williams & Beard 2009, p. 300.

- ^ a b Sargent 2004, p. 46.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d Tuck 2001, p. 20.

- ^ a b Davis 1998, p. 179.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Davis 1998, p. 183.

- ^ Tuck 2001, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 23.

- ^ a b Newman 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 44.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 36.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Tuck 2001, p. 30.

- ^ Tuck 2001, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 37.

- ^ a b Tuck 2001, p. 26.

- ^ Tuck 2001, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Myrick-Harris 2013, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Myrick-Harris 2013, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d Myrick-Harris 2013, p. 97.

- ^ a b Roche 1998, p. 10.

- ^ Roche 1998, p. 134.

- ^ Bryant 2023.

- ^ a b c Tuck 2001, p. 47.

- ^ Tuck 1995, p. 552.

- ^ Davis 1998, pp. 184–185.

- ^ a b Russell 2012, p. 780.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Davis 1998, p. 185.

- ^ a b c Tuck 2001, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e f Davis 1998, p. 184.

- ^ a b c Myrick-Harris 2013, p. 99.

- ^ Myrick-Harris 2013, pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tuck 2001, p. 49.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 50.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 34.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 46.

- ^ a b Roche 1998, pp. 10–12.

- ^ a b c Skutch 2013.

- ^ a b Tuck 1995, p. 550.

- ^ a b c Lloyd 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Elmore 2020.

- ^ a b c d Sargent 2004, p. 48.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d Kirkland 2020.

- ^ a b c d Ling & Deverick 2023, p. 185.

- ^ a b Russell 2012, p. 781.

- ^ a b c d e f Mitchell 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Savannah Morning News 2016.

- ^ Russell 2012, p. 773.

- ^ a b c d Davis 1998, p. 181.

- ^ a b c d e f Georgia Historical Society 2019.

- ^ a b c Segedy 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Georgia Historical Society 2016a.

- ^ a b c Myrick-Harris 2013, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Sargent 2004, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e f Tuck 1995, p. 546.

- ^ a b c d e Richardson & Luker 2014, p. 395.

- ^ a b c d Roche 1998, p. 130.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Roche 1998, p. 218.

- ^ a b Roche 1998, p. 140.

- ^ Roche 1998, p. 94.

- ^ a b Davis 1998, p. 186.

- ^ a b c d e Davis 1998, p. 187.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Davis 1998, p. 182.

- ^ a b c d Tuck 1995, p. 543.

- ^ a b Tuck 1995, p. 540.

- ^ Burkhart 2022.

- ^ a b c d Russell 2012, p. 782.

- ^ Haynes 2012, p. 24.

- ^ Haynes 2012, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b c Haynes 2012, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e Richardson & Luker 2014, p. 495.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Russell 2012, p. 788.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tuck 1995, p. 547.

- ^ Newman 2004, p. 85.

- ^ Tuck 1995, pp. 542, 549.

- ^ Georgia Historical Society 2017.

- ^ a b c Davis 1998, p. 188.

- ^ a b c d e f Russell 2012, p. 783.

- ^ Davis 1998, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Tuck 1995, p. 555.

- ^ Luders 2010, p. 46.

- ^ The Atlanta Constitution 1961, p. 16.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 132.

- ^ Tuck 1995, pp. 547–548.

- ^ Russell 2012, p. 784.

- ^ a b c Davis 1998, pp. 182–183.

- ^ a b c Russell 2012, p. 789.

- ^ Luders 2010, p. 63.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Richardson & Luker 2014, p. 396.

- ^ United States House Committee on the Judiciary 1963, pp. 1316–1317.

- ^ a b United States House Committee on the Judiciary 1963, p. 1317.

- ^ a b c d United States House Committee on the Judiciary 1963, p. 1318.

- ^ a b c d United States House Committee on the Judiciary 1963, p. 1319.

- ^ a b c Sokol 2006, p. 205.

- ^ Luders 2010, p. 91.

- ^ Richardson & Luker 2014, pp. xxiii, 396.

- ^ a b Savannah Morning News 2021.

- ^ Tuck 2020.

- ^ a b Miller 2023, p. 40.

- ^ Tuck 1995, p. 554.

- ^ Russell 2012, p. 779.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 5.

- ^ Tuck 2001, pp. 59–61.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 56.

- ^ Roche 1998, p. 150.

- ^ Tuck 1995, p. 549.

- ^ Tuck 1995, p. 544.

- ^ Tuck 2001, p. 109.

- ^ Tuck 1995, p. 539.

- ^ Tuck 1995, pp. 548–549.

- ^ Russell 2012, p. 790.

- ^ Ling & Deverick 2023, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Ling & Deverick 2023, p. 186.

Sources

- "Savannah Sit-In Ends in Violence". The Atlanta Constitution. Cox Enterprises. March 16, 1961. p. 16. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- Bryant, Maxine L. (May 12, 2023). "Lowcountry Blacks have resisted oppression since the first enslaved Africans arrived". Savannah Morning News. Gannett. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- Burkhart, Richard (June 20, 2022) [June 19, 2022]. "Juneteenth celebrated with joy and reverence at annual Tybee Wade-In". Savannah Morning News. Gannett. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- Davis, Townsend (1998). Weary Feet, Rested Souls: A Guided History of the Civil Rights Movement. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-04592-7.

- Elmore, Charles J. (August 24, 2020) [January 23, 2004]. "W. W. Law". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- "Georgia Historical Society to Dedicate New Civil Rights Trail Historical Marker to Savannah Protest Movement". Georgia Historical Society. September 21, 2016a. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- "Malcolm R. Maclean (1919–2001)". Georgia Historical Society. November 28, 2017. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- "Marker Monday: The Georgia Civil Rights Trail: The Savannah Protest Movement". Georgia Historical Society. February 11, 2019. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- Gottlieb, Martin (August 8, 1991). "Jim Crow's Ghost; Savannah and Civil Rights – A Special Report; Ways of Older South Linger In City of Thomas's Boyhood". The New York Times. With Peter Applebome. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- Haynes, Stephen R. (2012). The Last Segregated Hour: The Memphis Kneel-Ins and the Campaign for Southern Church Desegregation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-987530-6.

- Kirkland, W. Michael (August 14, 2020) [March 24, 2006]. "Hosea Williams". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- Ling, Peter J.; Deverick, David (2023). Martin Luther King Jr.: A Reference Guide to His Life and Works. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-1359-2.

- Lloyd, Wanda (December 29, 2022). "Happy birthday, W.W. Law. Savannah civil rights icon would have turned 100 on New Year's Day". Savannah Morning News. Gannett. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- Luders, Joseph E. (2010). The Civil Rights Movement and the Logic of Social Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-11651-0.

- Miller, Elizabeth Ellis (2023). Liturgy of Change: Rhetorics of the Civil Rights Mass Meeting. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-64336-390-5.

- Mitchell, Jerry (March 16, 2023). "On this day in 1960". Mississippi Today. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- Myrick-Harris, Clarissa (2013). ""Call the Women": The Tradition of African American Female Activism in Georgia during the Civil Rights Movement". In Glasrud, Bruce A.; Pitre, Merline (eds.). Southern Black Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. pp. 95–116. ISBN 978-1-60344-999-1.

- Newman, Mark (2004). The Civil Rights Movement. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-98529-5.

- Richardson, Christopher M.; Luker, Ralph E. (2014). Historical Dictionary of the Civil Rights Movement (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-8037-5.

- Roche, Jeff (1998). Restructured Resistance: The Sibley Commission and the Politics of Desegregation in Georgia. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-1979-7.

- Russell, Clare (October 2012). "Upheaval in Savannah: The Protest Cycle of a 'Short' Civil Rights Movement". Journal of Contemporary History. 47 (4). SAGE Publications: 773–792. doi:10.1177/0022009412451289. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 23488395. S2CID 144275631.

- Sargent, Frederic O. (2004). The Civil Rights Revolution: Events and Leaders, 1955–1968. Foreword by Bill Maxwell. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-8422-5.

- "Editorial: Savannah Protest Movement brought us here". Savannah Morning News. September 21, 2016. Archived from the original on September 7, 2023. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- "Beacon Our View: The struggle for civil rights is far from over". Savannah Morning News. Gannett. February 10, 2021 [February 9, 2021]. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- Segedy, Andria (January 25, 2020). "Civil rights activists talk Savannah's past". Savannah Morning News. Gannett. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- Skutch, Jan (August 18, 2013). "1963, desegregation changed the lives of 19 Savannah teens, society". Savannah Morning News. Gannett. Archived from the original on February 2, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- Sokol, Jason (2006). There Goes My Everything: White Southerners in the Age of Civil Rights, 1945–1975. New York City: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-26356-8.

- Tuck, Stephen (Fall 1995). "A City Too Dignified to Hate: Civic Pride, Civil Rights, and Savannah in Comparative Perspective". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 79 (3). Georgia Historical Society: 539–559. ISSN 0016-8297. JSTOR 40583288.

- Tuck, Stephen G. N. (2001). Beyond Atlanta: The Struggle for Racial Equality in Georgia, 1940–1980. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-2265-0.

- Tuck, Stephen (August 24, 2020) [September 9, 2004]. "Civil Rights Movement". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on May 27, 2023. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- Hearing Before Subcommittee No. 5 of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, Eighty-Eights Congress, First Session, on Miscellaneous Proposals Regarding the Civil Rights of Persons within the Jurisdiction of the United States. Part II. United States House Committee on the Judiciary. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1963.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Williams, Horace Randall; Beard, Ben (2009). This Day in Civil Rights History. Montgomery, Alabama: NewSouth Books. ISBN 978-1-58838-241-2.

Further reading

- "The Georgia Civil Rights Trail: The Savannah Protest Movement". Georgia Historical Society. September 29, 2016b. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- Hornsby, Alton Jr. (2011). "Georgia". In Hornsby, Alton Jr. (ed.). Black America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 187–212. ISBN 978-1-57356-976-7.

- Rice, Rolundus R. (2021). Hosea Williams: A Lifetime of Defiance and Protest. Foreword by Andrew Young. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-64336-258-8.

- Vines, Tykeia (March 22, 2018). "The Savannah Protest Movement". Georgia Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 5, 2023. Retrieved September 9, 2023.