Contents

The Torwali people are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group located in the Swat district of Pakistan. The Torwali people have a culture that values the telling of folktales and music that is played using the sitar.[1] They speak an Indo-Aryan language called Torwali.[2]

Description

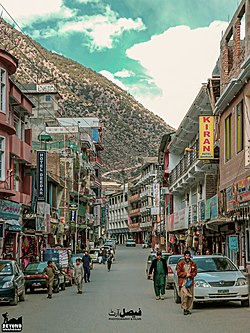

The Torwalis inhabit the Swat River valley between Laikot (a little south of Kalam) down to and including the village of Bahrein (60 km north of Mingora). The Torwalis live in compact villages of up to 600 houses, mainly on the west bank of the Swat River. Fredrik Barth estimated that they constituted about 2000 households in all in 1956. All the Torwalis he met were bilingual, speaking Pashto and Torwali.[3]

History

The Torwali people are believed to be among the earliest natives to the region of Swat.[2] The Torwali language is the closest modern Indo-Aryan language still spoken today to Niya, a dialect of Gāndhārī, a Middle Indo-Aryan language spoken in the ancient region of Gandhara.[4][5] The Torwalis were native to a more extensive area, such as towards Buner, from where they were expelled into mountainous tracts by successive aggressive migration by Pashtuns.[6] They are referred by pashtuns as "Kohistanis", which was the name given by them to "all Muhammadis (صلى الله عليه وسلم) of Indian descent in the Hindu Kush valleys".[7]

By the 17th century, in the aftermath of Yusufzai Pashtun invasions in the region, most of the Torwalis had converted from Hinduism and Buddhism to Islam; however, the strand was mostly superficial and elements of traditional culture were still heavily practised.[8][9]

Language

The Torwali people speak the Torwali language, an Indo-Aryan language of the Dardic (Kohistani) subgroup; the language was first documented by colonial archaeologist Aurel Stein in around 1925, and the records were published by George Abraham Grierson as 'Torwali: An Account of a Dardic Language of the Swat Kohistan' in 1929.[2][10]

It had approximately 102,000 speakers in 2016[10] and by 2017, eight schools with instruction in the Torwali language had been established for Torwali students.[11] Before 2007, the language did not have a written tradition.[11]

Culture

Unique to the Torwali people are traditional games, which were abandoned for more than six decades.[11] A festival held in Bahrain known as Simam attempted to revive them in 2011.[11] The Torwali people have a tradition of telling folktales.[12]

Music

The Torwali people play music using the traditional South Asian instrument known as the sitar.[1] Modern Torwali songs influenced by Urdu or Pashtu music are known as phal.[1]

References

- ^ a b c Torwali, Zubair (12 February 2016). "Fading songs from the hills". The Friday Times. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Shah, Danial (30 September 2013). "Torwali is a language". Himal Southasian. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ Barth 1956, p. 69.

- ^ Burrow, T. (1936). "The Dialectical Position of the Niya Prakrit". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 8 (2/3): 419–435. ISSN 1356-1898. JSTOR 608051.

... It might be going too far to say that Torwali is the direct lineal descendant of the Niya Prakrit, but there is no doubt that out of all the modern languages it shows the closest resemblance to it. A glance at the map in the Linguistic Survey of India shows that the area at present covered by "Kohistani" is the nearest to that area round Peshawar, where, as stated above, there is most reason to believe was the original home of the Niya Prakrit. That conclusion, which was reached for other reasons, is thus confirmed by the distribution of the modern dialects.

- ^ Salomon, Richard (10 December 1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- ^ Biddulph, John (1880). Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh. Office of the superintendent of government printing. pp. 69–70.

...they must have once occupied some extensive valley like Boneyr, from whence they, like the rest, have been expelled and thrust up into the more mountainous tracts by the aggressive Afghans. By the Afghans they are called Kohistanis, a name given everywhere by Pathans to Mussulmans of Indic descent, living in the Hindoo Koosh Valleys.

- ^ Barth 1956, p. 52. The Pathans call them, and all other Muhammadans of Indian descent in the Hindu Kush valleys, Kohistanis.

- ^ Scerrato, Umberto (1983). "Labyrinths in the Wooden Mosques of North Pakistan. A Problematic Presence". East and West. 33 (1/4): 21–29. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29756645.

According to the 13th century Tibetan Buddhist O rgyan pa forms of magic and Tantra Buddhism and Hindu cults still survived in the Swāt area even though Islam had begun to uproot them (G. Tucci, 1971, p. 375). Islam finally established itself in Swāt only with the invasion of the Yusufzai in the 16th century, (Bellew, 1864, pp. 65-67; Raverty, 1878, p. 206); ... it must nevertheless have been an Islam superficially accepted by the local population, some of the ancient traditions still being very much alive: ... The Torwali of upper Swāt would have been converted to Islam during the course of the 17th century (Biddulph, p. 70).

- ^ Bagnera, Alessandra (2006). "Preliminary Note on the Islamic Settlement of Udegram, Swat: The Islamic Graveyard (11th-13th century A.D.)". East and West. 56 (1/3): 205–228. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29757687.

- ^ a b Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2020). "Torwali". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (23 ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d Torwali, Zubair (18 February 2019). "Early Writing in Torwali in Pakistan". In Sherris, Ari; Peyton, Joy Kreeft (eds.). Teaching Writing to Children in Indigenous Languages : Instructional Practices from Global Contexts. Routledge. pp. 44–69. doi:10.4324/9781351049672-3. ISBN 978-1-351-04967-2. S2CID 187240076.

- ^ Torwali, Zubair (12 February 2016). "Fading songs from the hills". The Friday Times. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

Sources

- Barth, Fredrik (1956), "Torwali", Indus and Swat Kohistan: An ethnographic survey, Oslo: Forenede Trykkerier – via archive.org

Further reading

- Rehman, Abdur (1976), The Last Two Dynasties of the Sahis (PDF), Australian National University

- Stein, Aurel (1930), An Archaeological Tour in Upper Swat and Adjacent Hill Tracts, Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India, Government of India, Central Publication Branch