Contents

| This article is part of a series on |

| Political divisions of the United States |

|---|

|

| First level |

|

|

| Second level |

|

| Third level |

|

|

| Fourth level |

| Other areas |

|

|

|

United States portal |

Tribal sovereignty in the United States is the concept of the inherent authority of Indigenous tribes to govern themselves within the borders of the United States.

Originally, the U.S. federal government recognized American Indian tribes as independent nations and came to policy agreements with them via treaties. As the U.S. accelerated its westward expansion, internal political pressure grew for "Indian removal", but the pace of treaty-making grew regardless. The Civil War forged the U.S. into a more centralized and nationalistic country, fueling a "full bore assault on tribal culture and institutions", and pressure for Native Americans to assimilate.[3] In the Indian Appropriations Act of 1871, Congress prohibited any future treaties. This move was steadfastly opposed by Native Americans.[3]

Currently, the U.S. recognizes tribal nations as "domestic dependent nations"[4] and uses its own legal system to define the relationship between the federal, state, and tribal governments.

Native American sovereignty and the Constitution

The United States Constitution mentions Native American tribes three times:

- Article I, Section 2, Clause 3 states that "Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States ... excluding Indians not taxed."[5] According to Story's Commentaries on the U.S. Constitution, "There were Indians, also, in several, and probably in most, of the states at that period, who were not treated as citizens, and yet, who did not form a part of independent communities or tribes, exercising general sovereignty and powers of government within the boundaries of the states."

- Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution states that "Congress shall have the power to regulate Commerce with foreign nations and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes",[6] determining that Indian tribes were separate from the federal government, the states, and foreign nations;[7] and

- The Fourteenth Amendment, Section 2 amends the apportionment of representatives in Article I, Section 2 above.[8]

These constitutional provisions, and subsequent interpretations by the Supreme Court (see below), are today often summarized in three principles of U.S. Indian law:[9][10][11]

- Territorial sovereignty: Tribal authority on Indian land is organic and is not granted by the states in which Indian lands are located.

- Plenary power doctrine: Congress, and not the Executive Branch or Judicial Branch, has ultimate authority with regard to matters affecting the Indian tribes. Federal courts give greater deference to Congress on Indian matters than on other subjects.

- Trust relationship: The federal government has a "duty to protect" the tribes, implying (courts have found) the necessary legislative and executive authorities to effect that duty.[12]

Early history

The Marshall Trilogy, 1823–1832

The Marshall Trilogy is a set of three Supreme Court decisions in the early nineteenth century affirming the legal and political standing of Indian nations.

- Johnson v. McIntosh (1823), holding that private citizens could not purchase lands from Native Americans.

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), holding the Cherokee nation dependent, with a relationship to the United States like that of a "ward to its guardian".

- Worcester v. Georgia (1832), which laid out the relationship between tribes and the state and federal governments, stating that the federal government was the sole authority to deal with Indian nations.[13]

Indian Appropriations Act of 1871

Originally, the United States had recognized the Indian Tribes as independent nations, but after the Civil War, the U.S. suddenly changed its approach.[3]

The Indian Appropriations Act of 1871 had two significant sections. First, the Act ended United States recognition of additional Native American tribes or independent nations and prohibited additional treaties. Thus, it required the federal government no longer interact with the various tribes through treaties, but rather through statutes:

That hereafter no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty: Provided, further, that nothing herein contained shall be construed to invalidate or impair the obligation of any treaty heretofore lawfully made and ratified with any such Indian nation or tribe.

The 1871 Act also made it a federal crime to commit murder, manslaughter, rape, assault with intent to kill, arson, burglary, and larceny within any Territory of the United States.[citation needed]

Empowerment of tribal courts, 1883

On April 10, 1883, five years after establishing Indian police powers throughout the various reservations, the Indian Commissioner approved rules for a "court of Indian offenses". The court provided a venue for prosecuting criminal charges but afforded no relief for tribes seeking to resolve civil matters. Another five years later, Congress began providing funds to operate the Indian courts.

While U.S. courts clarified some of the rights and responsibilities of states and the federal government toward the Indian nations within the new nation's first century, it was almost another century before United States courts determined what powers remained vested in the tribal nations. In the interim, as a trustee charged with protecting their interests and property, the federal government was legally entrusted with ownership and administration of the assets, land, water, and treaty rights of the tribal nations.

United States v. Kagama (1886)

The 1871 Act was affirmed in 1886 by the U.S. Supreme Court, in United States v. Kagama, which affirmed that the Congress has plenary power over all Native American tribes within its borders by rationalization that "The power of the general government over these remnants of a race once powerful ... is necessary to their protection as well as to the safety of those among whom they dwell".[16] The Supreme Court affirmed that the U.S. Government "has the right and authority, instead of controlling them by treaties, to govern them by acts of Congress, they being within the geographical limit of the United States. ... The Indians owe no allegiance to a State within which their reservation may be established, and the State gives them no protection."[17]

The General Allotment Act (Dawes Act), 1887

Passed by Congress in 1887, the "Dawes Act" was named for Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, Chairman of the Senate's Indian Affairs Committee. It came as another crucial step in attacking the tribal aspect of the Indians of the time. In essence, the act broke up the land of most all tribes into modest parcels to be distributed to Indian families, and those remaining were auctioned off to white purchasers. Indians who accepted the farmland and became "civilized" were made American citizens. But the Act itself proved disastrous for Indians, as much tribal land was lost, and cultural traditions destroyed. Whites benefited the most; for example, when the government made 2 million acres (8,100 km2) of Indian lands available in Oklahoma, 50,000 white settlers poured in almost instantly to claim it all (in a period of one day, April 22, 1889).

Evolution of relationships: The evolution of the relationship between tribal governments and federal governments has been glued together through partnerships and agreements. Also running into problems of course such as finances which also led to not being able to have a stable social and political structure at the helm of these tribes or states.[18]

Twentieth-century developments

| Part of a series on |

| Native Americans in the United States |

|---|

Revenue and Indian Citizenship acts, 1924

The Revenue Act of 1924 (Pub. L. 68–176, H.R. 6715, 43 Stat. 253, enacted June 2, 1924), also known as the Mellon tax bill after U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon, cut federal tax rates and established the U.S. Board of Tax Appeals, which was later renamed the United States Tax Court in 1942. The Revenue Act was applicable to incomes for 1924.[19] The bottom rate, on income under $4,000, fell from 1.5% to 1.125% (both rates are after reduction by the "earned income credit"). A parallel act, the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 (Pub. L. 68–175, H.R. 6355, 43 Stat. 253, enacted June 2, 1924), granted all non-citizen resident Indians citizenship.[20][21] Thus the Revenue Act declared that there were no longer any "Indians, not taxed" to be not counted for purposes of United States congressional apportionment. President Calvin Coolidge signed the bill into law.

Indian Reorganization Act, 1934

In 1934 the Indian Reorganization Act, codified as Title 25, Section 476 of the U.S. Code, allowed Indian nations to select from a catalogue of constitutional documents that enumerated powers for tribes and for tribal councils. Though the Act did not specifically recognize the Courts of Indian Offenses, 1934 is widely considered to be the year when tribal authority, rather than United States authority, gave the tribal courts legitimacy. John Collier and Nathan Margold wrote the solicitor's opinion, "Powers of Indian Tribes" which was issued October 25, 1934, and commented on the wording of the Indian Reorganization Act. This opinion stated that sovereign powers inhered in Indian tribes except for where they were restricted by Congress. The opinion stated that "Conquest has brought the Indian tribes under the control of Congress, but except as Congress has expressly restricted or limited the internal powers of sovereignty vested in the Indian tribes such powers are still vested in the respective tribes and may be exercised by their duly constituted organs of government."[22]

Public Law 280, 1953

In 1953, Congress enacted Public Law 280, which gave some states extensive jurisdiction over the criminal and civil controversies involving Indians on Indian lands. Many, especially Indians, continue to believe the law unfair because it imposed a system of laws on the tribal nations without their approval.

In 1965 the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit concluded that no law had ever extended provisions of the U.S. Constitution, including the right of habeas corpus, to tribal members brought before tribal courts. Still, the court concluded, "it is pure fiction to say that the Indian courts functioning in the Fort Belknap Indian community are not in part, at least, arms of the federal government. Originally they were created by federal executive and imposed upon the Indian community, and to this day the federal government still maintains a partial control over them." In the end however, the Ninth Circuit limited its decision to the particular reservation in question and stated, "it does not follow from our decision that the tribal court must comply with every constitutional restriction that is applicable to federal or state courts."

While many modern courts in Indian nations today have established full faith and credit with state courts, the nations still have no direct access to U.S. courts. When an Indian nation files suit against a state in U.S. court, they do so with the approval of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. In the modern legal era, the courts and Congress have, however, further refined the often competing jurisdictions of tribal nations, states and the United States in regard to Indian law.

In the 1978 case of Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, the Supreme Court, in a 6–2 opinion authored by Justice William Rehnquist, concluded that tribal courts do not have jurisdiction over non-Indians (the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court at that time, Warren Burger, and Justice Thurgood Marshall filed a dissenting opinion). But the case left unanswered some questions, including whether tribal courts could use criminal contempt powers against non-Indians to maintain decorum in the courtroom, or whether tribal courts could subpoena non-Indians.

A 1981 case, Montana v. United States, clarified that tribal nations possess inherent power over their internal affairs, and civil authority over non-members on fee-simple lands within its reservation when their "conduct threatens or has some direct effect on the political integrity, the economic security, or the health or welfare of the tribe."

Other cases of those years precluded states from interfering with tribal nations' sovereignty. Tribal sovereignty is dependent on, and subordinate to, only the federal government, not states, under Washington v. Confederated Tribes of Colville Indian Reservation (1980). Tribes are sovereign over tribal members and tribal land, under United States v. Mazurie (1975).[13]

In Duro v. Reina, 495 U.S. 676 (1990), the Supreme Court held that a tribal court does not have criminal jurisdiction over a non-member Indian, but that tribes "also possess their traditional and undisputed power to exclude persons who they deem to be undesirable from tribal lands. ... Tribal law enforcement authorities have the power if necessary, to eject them. Where jurisdiction to try and punish an offender rests outside the tribe, tribal officers may exercise their power to detain and transport him to the proper authorities." In response to this decision, Congress passed the 'Duro Fix', which recognizes the power of tribes to exercise criminal jurisdiction within their reservations over all Indians, including non-members. The Duro Fix was upheld by the Supreme Court in United States v. Lara, 541 U.S. 193 (2004).

Iron Crow v. Oglala Sioux Tribe (1956)

In Iron Crow v. Oglala Sioux Tribe, the United States Supreme Court concluded that two Oglala Sioux defendants convicted of adultery under tribal laws, and another challenging a tax from the tribe, were not exempted from the tribal justice system because they had been granted U.S. citizenship. It found that tribes "still possess their inherent sovereignty excepting only when it has been specifically taken from them by treaty or Congressional Act". This means American Indians do not have exactly the same rights of citizenship as other American citizens. The court cited case law from a pre-1924 case that said, "when Indians are prepared to exercise the privileges and bear the burdens of" sui iuris, i.e. of one's own right and not under the power of someone else, "the tribal relation may be dissolved and the national guardianship brought to an end, but it rests with Congress to determine when and how this shall be done, and whether the emancipation shall be complete or only partial" (U.S. v. Nice, 1916). The court further determined, based on the earlier Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock case, that "It is thoroughly established that Congress has plenary authority over Indians." The court held that, "the granting of citizenship in itself did not destroy ... jurisdiction of the Indian tribal courts and ... there was no intention on the part of Congress to do so." The adultery conviction and the power of tribal courts were upheld.

Further, the court held that whilst no law had directly established tribal courts, federal funding "including pay and other expenses of judges of Indian courts" implied that they were legitimate courts. Iron Crow v. Oglala Sioux Tribe, 231 F.2d 89 (8th Cir. 1956) ("including pay and other expenses of judges of Indian courts").

Tribal governments today

Tribal courts

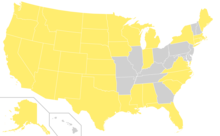

At the dawn of the 21st century, the powers of tribal courts across the United States varied, depending on whether the tribe was in a Public Law 280 (PL280) state (Alaska, California, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon, and Wisconsin).

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the 1978 decision Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe that tribes have no jurisdiction over non-Indians. Tribal courts maintain much criminal jurisdiction over their members, and because of the Duro fix, also over non-member Indians regarding crime on tribal land. The Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 expanded the criminal jurisdiction of tribes over non-Indian perpetrators of domestic violence that occur in Indian Country when the victim is Indian.[23]

The 1968 Indian Civil Rights Act limited tribal punishment to one year in jail and a $5,000 fine,[24] but this was expanded by the Tribal Law and Order Act of 2010.

While tribal nations do not enjoy direct access to U.S. courts to bring cases against individual states, as sovereign nations they do enjoy immunity against many lawsuits,[25] unless a plaintiff is granted a waiver by the tribe or by congressional abrogation.[26] The sovereignty extends to tribal enterprises[27] and tribal casinos or gaming commissions.[28] The Indian Civil Rights Act does not allow actions against an Indian tribe in federal court for deprivation of substantive rights, except for habeas corpus proceedings.[25]

Tribal and pueblo governments today launch far-reaching economic ventures, operate growing law enforcement agencies, and adopt codes to govern conduct within their jurisdiction, while the United States retains control over the scope of tribal law making. Laws adopted by Native American governments must also pass the Secretarial Review of the Department of Interior through the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

With crime twice as high on Indian lands, federal funding of tribal courts has been criticized by the United States Commission on Civil Rights and the Government Accountability Office as inadequate to allow them to perform necessary judicial functions, such as hiring officials trained in law, and prosecuting cases neglected by the federal government.[29]

Nation to nation: tribes and the federal government

The United States Constitution specifically mentions American Indians three times. Article I, Section 2, Clause 3 and the Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment address the handling of "Indians not taxed" in the apportionment of the seats of the House of Representatives according to population and in so doing suggest that Indians need not be taxed. In Article I Section 8, Clause 3, Congress is empowered to "regulate commerce with foreign nations…states…and with the Indian tribes." Technically, Congress has no more power over Indian nations than it does over individual states. In the 1970s, Native American self-determination replaced Indian termination policy as the official United States policy towards Native Americans.[30] Self-determination promoted the ability of tribes to self-govern and make decisions concerning their people. In dealing with Indian policy, a separate agency, the Bureau of Indian Affairs has been in place since 1824.

The idea that tribes have an inherent right to govern themselves is at the foundation of their constitutional status – the power is not delegated by congressional acts. Congress can, however, limit tribal sovereignty. Unless a treaty or federal statute removes a power, however, the tribe is assumed to possess it.[31] Current federal policy in the United States recognizes this sovereignty and stresses the government-to-government relations between the United States and Federally recognized tribes.[32] However, most Native American land is held in trust by the United States,[33] and federal law still regulates the economic rights of tribal governments and political rights. Tribal jurisdiction over persons and things within tribal borders are often at issue. While tribal criminal jurisdiction over Native Americans is reasonably well settled, tribes are still striving to achieve criminal jurisdiction over non-Native persons who commit crimes in Indian Country. This is largely due to the Supreme Court's ruling in 1978 in Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe that tribes lack the inherent authority to arrest, try and convict non-Natives who commit crimes on their lands (see below for additional discussion on this point.)

As a result of a pair of treaties in 1830s, two tribal nations (the Cherokee and Choctaw) each have the right to send non-voting members to the United States House of Representatives (similar to a non-state U.S. territory or the federal district); the Choctaw have never exercised their right to do so since they were given the power and the Cherokee had not done so until appointing a delegate in 2019, though this delegate has not been accepted by Congress.[34][35][36]

Tribal state relations: sovereign within a sovereign

Another dispute over American Indian government is its sovereignty versus that of the states. The federal U.S. government has always been the government that makes treaties with Indian tribes – not individual states. Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution states that "Congress shall have the power to regulate Commerce with foreign nations and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes".[6] This determined that Indian tribes were separate from the federal or state governments and that the states did not have power to regulate commerce with the tribes, much less regulate the tribes. The states and tribal nations have clashed over many issues such as Indian gaming, fishing, and hunting. American Indians believed that they had treaties between their ancestors and the United States government, protecting their right to fish, while non-Indians believed the states were responsible for regulating commercial and sports fishing.[37] In the case Menominee Tribe v. United States in 1968, it was ruled that "the establishment of a reservation by treaty, statute or agreement includes an implied right of Indians to hunt and fish on that reservation free of regulation by the state".[38] States have tried to extend their power over the tribes in many other instances, but federal government ruling has continuously ruled in favor of tribal sovereignty. A seminal court case was Worcester v. Georgia. Chief Justice Marshall found that "England had treated the tribes as sovereign and negotiated treaties of alliance with them. The United States followed suit, thus continuing the practice of recognizing tribal sovereignty. When the United States assumed the role of protector of the tribes, it neither denied nor destroyed their sovereignty."[39] As determined in the Supreme Court case United States v. Nice (1916),[40] U.S. citizens are subject to all U.S. laws even if they also have tribal citizenship.

In July 2020, the U.S Supreme Court ruled in McGirt v. Oklahoma that the state of Oklahoma acted outside its jurisdiction when trying a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in 1997 for rape and that the case should have been tried in federal court since Congress had never officially dissolved the reservation in question.[41] The ruling's expansion of jurisdiction sovereignty also opened the possibility for Native Americans to obtain more power in alcohol regulation and casino gambling.[42]

Similar to the promised non-voting tribal delegates in the United States House of Representatives, the Maine House of Representatives maintains three state-level non-voting seats for representatives of the Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, and the Penobscot.[43] Two of the seats are currently not filled in protest over issues of tribal sovereignty and rights.[44]

Tribal sovereignty over land and natural resources

Following industrialization, the 1800s brought many challenges to tribal sovereignty over tribal members' occupied lands in the United States. In 1831, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia established a trust relationship between the United States and tribal territories. This gave the U.S. federal government primary jurisdictional authority over tribal land use, while maintaining tribal members' rights to reside on their land and access its resources.[45] Similarly, in 1841, a treaty between the U.S. federal government and the Mole Lake Band of Sokaogon Chippewa resulted in the Chippewa ceding extensive lands to the U.S., but maintaining usufructuary rights to fishing, hunting, and gathering in perpetuity on all ceded land.[46]

Wartime industry of the early 1900s introduced uranium mining and the need for weapons testing sites, for which the U.S. federal government often selected former and current tribal territories in the southwestern deserts.[47] Uranium mines were constructed upstream of Navajo and Hopi reservations in Arizona and Nevada, measurably contaminating Native American water supply through the 1940s and 1950s with lasting impacts to this day.[48] The Nevada desert was also a common nuclear testing site for the U.S. military through World War II and the Cold War, the closest residents being Navajo Nation members.[49]

In 1970, President Richard Nixon established the federal government's Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).[50] In 1974, the EPA became the first U.S. federal agency to release an Indian Policy, which established the model of environmental federalism operational today. Under this model, the federal EPA sets water, air, and waste disposal standards, but delegates enforcement authority and the opportunity to design stricter environmental regulations to each state. Enforcement authority over Native American territory, however, remains under federal EPA jurisdiction, unless a given tribe applies for and is granted Treatment as State (TAS) status.[51]

With the emergence of environmental justice movements in the United States through the 1990s, President Bill Clinton released executive orders 12898 (1994) and 13007 (1996). EO 12898 affirmed disparate impacts of climate change as stratified by socioeconomic status; EO 13007 ordered the protection of Native American cultural sites.[49] Since the passage of EO 12898 and EO 13007, tribal prosecutors have litigated extensively against the federal government and industry polluters over land use and jurisdiction with varying degrees of success.

In 2007, the U.N. adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People ("The Declaration"), despite the United States voting against it along with Australia, New Zealand, and Canada.[52][49] In 2010, President Barack Obama revisited The Declaration and declared that the U.S. government now supported it;[49] however, as of December 2022, the requirements of The Declaration have still not been adopted into U.S. law. As recently as 2015, the Gold King Mine contaminated three million gallons of water in the Colorado River which serves as drinking water for the Navajo and Hopi downstream. The federal EPA appropriated $156,000 in reparations for Gold King Mine, while the Flint, Michigan water crisis in 2014 received $80 million in federal funds.[53]

A recent challenge faced by Native Americans regarding land and natural resource sovereignty has been posed by the modern real estate market. While Native Nations have made substantial progress in land and resource sovereignty, such authority is limited to land classified as 'Native American owned.' In the private real estate market, however, big industry polluters and hopeful miners have made a practice of buying out individual landowners in Native American residential areas, subsequently using that land to build mines or factories which increase local pollution. There is not regulation or legislation in place to sufficiently curb this practice at the rate necessary to preserve Native American land and natural resources.[49]

In 2023, the federally-recognized Resighini Rancheria of the Yurok People, Tolowa Dee-ni' Nation, and Cher-Ae Heights Indian Community of the Trinidad Rancheria announced that as territorial governments they have protected the Yurok-Tolowa-Dee-ni' Indigenous Marine Stewardship Area of 700 square miles (1,800 km2) of ocean waters and coastline reaching from Oregon to just south of Trinidad in the Redwood National and State Parks. [54]

List of cases

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831) (established trust relationship between Native American lands and the U.S. federal government)

- United States v. Holiday, 70 U.S. 407 (1866) (holding that a congressional ban on selling liquor to the Indians was constitutional)

- Sarlls v. United States, 152 U.S. 570 (1894) (holding that lager beer is not spiritous liquor nor wine within the meaning of those terms as used in Revised Statutes § 2139)

- In re Heff, 197 U.S. 488 (1905) (holding that Congress has the power to place the Indians under state law if it chooses, and the ban on selling liquor does not apply to Indians subject to the Allotment acts)

- Iron Crow v. Ogallala Sioux Tribe, 129 F. Supp. 15 (1955) (holding that tribes have power to create and change their court system and that power is limited only by Congress, not the courts)

- United States v. Washington (1974) also known as the Boldt Decision (concerning off-reservation fishing rights: holding that Indians had an easement to go through private property to their fishing locations, that the state could not charge Indians a fee to fish, that the state could not discriminate against the tribes in the method of fishing allowed, and that the Indians had a right to a fair and equitable share of the harvest)

- Wisconsin Potowatomies of Hannahville Indian Community v. Houston, 393 F. Supp. 719 (holding that tribal law and not state law governs the custody of children domiciled on reservation land)

- Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191 (1978) (holding that Indian tribal courts do not have inherent criminal jurisdiction to try and to punish non-Indians, and hence may not assume such jurisdiction unless specifically authorized to do so by Congress.)

- Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe, 455 U.S. 130 (1982) (holding that Indian Nations have the power to tax Non-Native Americans based on their power as a nation and treaty rights to exclude others; this right can be curtailed only by Congress.)

- American Indian Agricultural Credit Consortium, Inc. v. Fredericks, 551 F. Supp. 1020 (1982) (holding that federal, not state courts have jurisdiction over tribal members)

- Maynard v. Narrangansett Indian Tribe, 798 F. Supp. 94 (1992) (holding that tribes have sovereign immunity against state tort claims)

- Venetie I.R.A. Council v. Alaska, 798 F. Supp. 94 (holding that tribes have power to recognize and legislate adoptions)

- Native American Church v. Navajo Tribal Council, 272 F.2d 131 (holding that the First Amendment does not apply to Indian nations unless it is applied by Congress)

- Teague v. Bad River Band, 236 Wis. 2d 384 (2000) (holding that tribal courts deserve full faith and credit since they are the court of an independent sovereign; however, in order to end confusion, cases that are filed in state and tribal courts require consultation of both courts before they are decided.)

- Inyo County v. Paiute-Shoshone Indians (U.S. 2003) (holding that tribal sovereignty may override the search and seizure powers of a state)

- Sharp v. Murphy 591 U.S. ___ (2020), and McGirt v. Oklahoma 591 U.S. ___ (2020) (holding that if Congress did not expressly disestablish a reservation, the state wherein the reservation lies has no jurisdiction to prosecute crimes involving Indian defendants or Indian victims under the Major Crimes Act)

See also

- Aboriginal title in the United States

- Dawes Act

- Diplomatic recognition

- Indian country jurisdiction

- Indigenous rights

- Indigenous self-government in Canada

- List of Alaska Native tribal entities

- List of federally recognized tribes in the United States

- List of national legal systems

- Māori protest movement in New Zealand

- Native American reservation politics

- Native American self-determination

- Off-reservation trust land

- Political divisions of the United States

- Sovereignty

- Special district (United States)

- United States federal recognition of Native Hawaiians

Notes

- ^ a b "Frequently Asked Questions, Bureau of Indian Affairs". Department of the Interior. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ "Navajo Population Profile 2010 U.S. Census" (PDF). Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c "1871: The End of Indian Treaty-Making". NMAI Magazine. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ "Native American Policies". U.S. Department of Justice. June 16, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ Constitution of the United States of America: Article. I.

- ^ a b American Indian Policy Center. 2005. St. Paul, MN. 4 October 2008

- ^ Cherokee Nations v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831)

- ^ Additional amendments to the United States Constitution

- ^ Charles F. Wilkinson, Indian tribes as sovereign governments: a sourcebook on federal-tribal history, law, and policy, AIRI Press, 1988

- ^ Conference of Western Attorneys General, American Indian Law Deskbook, University Press of Colorado, 2004

- ^ N. Bruce Duthu, American Indians and the Law, Penguin/Viking, 2008

- ^ Robert J. McCarthy, The Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Federal Trust Obligation to American Indians, 19 BYU J. PUB. L. 1 (December, 2004)

- ^ a b Miller, Robert J. (March 18, 2021). "The Most Significant Indian Law Decision in a Century | The Regulatory Review". The Regulatory Review. University of Pennsylvania Law School. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ Onecle (November 8, 2005). "Indian Treaties". Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ^ 25 U.S.C. § 71. Indian Appropriation Act of March 3, 1871, 16 Stat. 544, 566

- ^ "U.S. v Kagama, 118 U.S. 375 (1886), Filed May 10, 1886". FindLaw, a Thomson Reuters business. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ "United States v. Kagama – 118 U.S. 375 (1886)". Justia. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ "Historical Tribal Sovereignty & Relations | Native American Financial Services Association". August 7, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ "1926". Statistics of Income, 1926 - FRASER - St. Louis Fed. 1926.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "The 1924 Indian Citizenship Act". Nebraskastudies.org. June 2, 1924. Archived from the original on June 5, 2009. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ^ Oklahoma State University Library. "Indian Affairs: Laws And Treaties. Vol. Iv, Laws". Digital.library.okstate.edu. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ^ Margold, Nathan R. "Powers of Indian Tribes". Solicitor's Opinions. University of Oklahoma College of Law. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ 25 U.S.C. § 1304, VAWA Reauthorization Act available at www.gpo.gov

- ^ Robert J. McCarthy, Civil Rights in Tribal Courts; The Indian Bill of Rights at 30 Years, 34 IDAHO LAW REVIEW 465 (1998).

- ^ a b Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez, 436 U.S. 49 (1978)

- ^ Oklahoma Tax Comm'n v. Citizen Band of Potawatomi Tribe of Okla., 498 U.S. 505 (1991)

- ^ Local IV-302 Int'l Woodworkers Union of Am. v. Menominee Tribal Enterprises, 595 F.Supp. 859 (E.D. Wis. 1984).

- ^ Barker v. Menominee Nation Casino, et al, 897 F.Supp. 389 (E.D. Wis. 1995).

- ^ United States Commission on Civil Rights (December 2018). "Broken Promises: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans" (PDF).

- ^ Wilkinson, Charles. Blood Struggle: The Rise of Modern Indian Nations. p 189. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2005.

- ^ Light, Steven Andrew, and Kathryn R.L. Rand. Indian Gaming and Tribal Sovereignty: The Casino Compromise. University Press of Kansas, 2005. (19)

- ^ "Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies". georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov.

- ^ Some tribal lands, most commonly in Oklahoma, are held by the tribe according to the original patent deed and thus are not trust property.

- ^ Ahtone, Tristan (January 4, 2017). "The Cherokee Nation Is Entitled to a Delegate in Congress. But Will They Finally Send One?". YES! Magazine. Bainbridge Island, Washington. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ^ Pommersheim, Frank (September 2, 2009). Broken Landscape: Indians, Indian Tribes, and the Constitution. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-19-970659-4. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ^ Krehbiel-Burton, Lenzy (August 23, 2019). "Citing treaties, Cherokees call on Congress to seat delegate from tribe". Tulsa World. Tulsa, Oklahoma. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ Wilkinson, Charles. Blood Struggle: The Rise of Modern Indian Nations. p151. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2005.

- ^ Canby Jr., William C. American Indian Law. p449. St. Paul, MN: West Group 1998.

- ^ Green, Michael D. and Perdue, Theda. However, England ceased to exist as a sovereign entity in 1707 to be replaced by Great Britain. Chief Justice Marshall's incorrect use of terminology appears to weaken the argument. The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears. Viking, 2007.

- ^ Lemont, Eric D. American Indian Constitutional Reform and the Rebuilding of Native Nations. University of Texas Press, 2006.

- ^ Wolf, Richard; Johnson, Kevin (July 9, 2020). "Supreme Court gives Native Americans jurisdiction over eastern half of Oklahoma". USA Today. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Hurley, Lawrence (July 9, 2020). "U.S. Supreme Court deems half of Oklahoma a Native American reservation". Reuters. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Starbird, Jr., S. Glenn (1983). "Brief History of Indian Legislative Representatives". Maine Legislature. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- ^ Moretto, Mario (May 26, 2015). "Passamaquoddy, Penobscot tribes withdraw from Maine Legislature". Bangor Daily News.

- ^ Teodoro, Manuel P.; Haider, Mellie; Switzer, David (October 24, 2016). "U.S. Environmental Policy Implementation on Tribal Lands: Trust, Neglect, and Justice". Policy Studies Journal. 46 (1): 37–59. doi:10.1111/psj.12187. ISSN 0190-292X.

- ^ Mandleco, Sarah (2002). "Surviving a State's Challenge to the EPA's Grant of Treatment as State Status under the Clean Water Act: One Tribe's Story State of Wisconsin v. EPA and Sokaogon Chippewa Community". Wisconsin Environmental Law Journal. 8: 197–224.

- ^ Rock, Tommy (2020). "Traditional Ecological Knowledge Policy Considerations for Abandoned Uranium Mines on Navajo Nation". Human Biology. 92 (1): 19–26. doi:10.13110/humanbiology.92.1.01. PMC 8477793. PMID 33231023 – via Wayne State University Press.

- ^ "Environmental Impacts". Navajo Nation. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Ornelas, Roxanne T. (October 21, 2011). "Managing the Sacred Lands of Native America". The International Indigenous Policy Journal. 2 (4). doi:10.18584/iipj.2011.2.4.6. ISSN 1916-5781.

- ^ "U.S. Environmental Protection Agency | US EPA". www.epa.gov. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

- ^ Diver, Sybil (2019). "Engaging Colonial Entanglements: "Treatment as a State" Policy for Indigenous Water Co-Governance". Global Environmental Politics. 19 (3): 33–56. doi:10.1162/glep_a_00517. S2CID 199537244.

- ^ UN adopts Declaration on Rights of Indigenous Peoples Archived September 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine United Nations News Centre, 13 September 2007.

- ^ Examining EPA's Unacceptable Response to Indian Tribes. Congressional Hearing, 2016-04-22, 2016.

- ^ Hill, Jos; Hayden, Bobby (January 26, 2024). "Tribal Nations Designate First US Indigenous Marine Stewardship Area". Pew Charitable Trusts. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

References

- Davies, Wade & Clow, Richmond L. (2009). American Indian Sovereignty and Law: An Annotated Bibliography. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

- Hays, Joel Stanford. "Twisting the Law: Legal Inconsistencies in Andrew Jackson's Treatment of Native-American Sovereignty and State Sovereignty." Journal of Southern Legal History, 21 (no. 1, 2013), 157–92.

- Macklem, Patrick (1993). "Distributing Sovereignty: Indian Nations and Equality of Peoples". Stanford Law Review. 45 (5): 1311–1367. doi:10.2307/1229071. JSTOR 1229071.

External links

- Kussel, Wm. F. Jr. Tribal Sovereignty and Jurisdiction (It's a Matter of Trust) Archived July 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- The Avalon Project: Treaties Between the United States and Native Americans

- Cherokee Nation v. the State of Georgia, 1831

- Prygoski, Philip J. From Marshall to Marshall: The Supreme Court's Changing Stance on Tribal Sovereignty

- From War to Self Determination, the Bureau of Indian Affairs

- NiiSka, Clara, Indian Courts, A Brief History, parts I, II, and III

- Public Law 280

- Religious Freedom with Raptors at archive.today (archived 2013-01-10) – details racism and attack on tribal sovereignty regarding eagle feathers

- San Diego Union Tribune, 17 December 2007: Tribal justice not always fair, critics contend (Tort cases tried in tribal courts)

- Sovereignty Revisited: International Law and Parallel Sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples