| Part of a series on |

| Wicca |

|---|

|

Wicca (English: /ˈwɪkə/), also known as "The Craft",[1] is a modern pagan, syncretic, earth-centered religion. Considered a new religious movement by scholars of religion, the path evolved from Western esotericism, developed in England during the first half of the 20th century, and was introduced to the public in 1954 by Gerald Gardner, a retired British civil servant. Wicca draws upon ancient pagan and 20th-century hermetic motifs for theological and ritual purposes. Doreen Valiente joined Gardner in the 1950s, further building Wicca's liturgical tradition of beliefs, principles, and practices, disseminated through published books as well as secret written and oral teachings passed along to initiates.

Many variations of the religion have grown and evolved over time, associated with a number of diverse lineages, sects, and denominations, referred to as traditions, each with its own organisational structure and level of centralisation. Given its broadly decentralised nature, disagreements arise over the boundaries that define Wicca. Some traditions, collectively referred to as British Traditional Wicca (BTW), strictly follow the initiatory lineage of Gardner and consider Wicca specific to similar traditions, excluding newer, eclectic traditions. Other traditions, as well as scholars of religion, apply Wicca as a broad term for a religion with denominations that differ on some key points but share core beliefs and practices.

Wicca is typically duotheistic, venerating both a Goddess and a God, traditionally conceived as the Triple Goddess and the Horned God, respectively. These deities may be regarded in a henotheistic way, as having many different divine aspects which can be identified with various pagan deities from different historical pantheons. For this reason, they are sometimes referred to as the "Great Goddess" and the "Great Horned God", with the honorific "great" connoting a personification containing many other deities within their own nature. Some Wiccans refer to the goddess as "Lady" and the god as "Lord" to invoke their divinity. These two deities are sometimes viewed as facets of a universal pantheistic divinity, regarded as an impersonal force rather than a personal deity. Other traditions of Wicca embrace polytheism, pantheism, monism, and Goddess monotheism.

Wiccan celebrations encompass both the cycles of the Moon, known as Esbats and commonly associated with the Triple Goddess, alongside the cycles of the Sun, seasonally based festivals known as Sabbats and commonly associated with the Horned God. The Wiccan Rede is a popular expression of Wiccan morality, often with respect to the ritual practice of magic.

Definition and terminology

Scholars of religious studies classify Wicca as a new religious movement,[2] and more specifically as a form of modern Paganism.[3] Wicca has been cited as the largest,[4] best known,[5] most influential,[6] and most academically studied form of modern Paganism.[7] Within the movement it has been identified as sitting on the eclectic end of the eclectic to reconstructionist spectrum.[8] Several academics have also categorised Wicca as a form of nature religion, a term that is also embraced by many of its practitioners,[9] and as a mystery religion.[10] However, given that Wicca also incorporates the practice of magic, several scholars have referred to it as a "magico-religion".[11] Wicca is also a form of Western esotericism, and more specifically a part of the esoteric current known as occultism.[12] Academics like Wouter Hanegraaff and Tanya Luhrmann have categorised Wicca as part of the New Age, although other academics, and many Wiccans themselves, dispute this categorisation.[13]

Although recognised as a religion by academics, some evangelical Christians have attempted to deny it legal recognition as such, while some Wiccan practitioners themselves eschew the term "religion" – associating the latter purely with organised religion – instead favouring "spirituality" or "way of life".[14] Although Wicca as a religion is distinct from other forms of contemporary Paganism, there has been much "cross-fertilization" between these different Pagan faiths; accordingly, Wicca has both influenced and been influenced by other Pagan religions, thus making clear-cut distinctions between them more difficult for religious studies scholars to make.[15] The terms wizard and warlock are generally discouraged in the community.[16] In Wicca, denominations are referred to as traditions,[14] while non-Wiccans are often termed cowans.[17]

Wiccan definition of "Witchcraft"

When the religion first came to public attention, its followers commonly called it "Witchcraft".[18][a] Gerald Gardner—the man regarded as the "Father of Wicca"—referred to it as the "Craft of the Wise", "Witchcraft", and "the Witch-cult" during the 1950s.[21] Gardner believed in the theory that persecuted witches had actually been followers of a surviving pagan religion, but this theory has now been proven wrong.[22] There is no evidence that he ever called it "Wicca", although he did refer to its community of followers as "the Wica" (with one c).[21] As a name for the religion, "Wicca" developed in Britain during the 1960s.[14] It is not known who first used this name for the religion, although one possibility is that it might have been Gardner's rival Charles Cardell, who was calling it the "Craft of the Wiccens" by 1958.[23] The first recorded use of the name "Wicca" was in 1962,[24] and it had been popularised to the extent that several British practitioners founded a newsletter called The Wiccan in 1968.[25]

Although pronounced differently, the Modern English term "Wicca" is derived from the Old English wicca [ˈwittʃɑ] and wicce [ˈwittʃe], the masculine and feminine term for witch, respectively, that was used in Anglo-Saxon England.[26] By adopting it for modern usage, Wiccans were both symbolically linking themselves to the ancient, pre-Christian past,[27] and adopting a self-designation that would be less controversial than "Witchcraft".[28] The scholar of religion and Wiccan priestess Joanne Pearson noted that while "the words 'witch' and 'wicca' are therefore linked etymologically, […] they are used to emphasize different things today".[29]

In early sources "Wicca" referred to the whole of the religion rather than to a specific tradition.[30] In following decades, members of certain traditions – those known as British Traditional Wicca – began claiming that only they should be called "Wiccan", and that other traditions must not use it.[31] From the late 1980s onwards, various books propagating Wicca were published that again used the former, broader definition of the word.[32] Thus, by the 1980s, there were two competing definitions of the word "Wicca" in use among the Pagan and esoteric communities, one broad and inclusive, the other narrow and exclusionary.[14] Among scholars of Pagan studies it is the older, broader, inclusive meaning which is preferred.[14]

Alongside "Wicca", some practitioners still call the religion "Witchcraft" or "the Craft".[33] Using the word "Witchcraft" in this context can result in confusion with other, non-religious meanings of "witchcraft" as well as other religions—such as Satanism and Luciferianism—whose practitioners also sometimes describe themselves as "Witches".[18] Another term sometimes used as a synonym for "Wicca" is "Pagan witchcraft",[18] although there are also other forms of modern Paganism—such as types of Heathenry—which also use the term "Pagan witchcraft".[34] From the 1990s onward, various Wiccans began describing themselves as "Traditional Witches", although this term was also employed by practitioners of other magico-religious traditions like Luciferianism.[35] In some popular culture, such as television programs Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Charmed, the word "Wicca" has been used as a synonym for witchcraft more generally, including in non-religious and non-Pagan forms.[36]

Beliefs

Theology

Theological views within Wicca are diverse.[37] The religion encompasses theists, atheists, and agnostics, with some viewing the religion's deities as entities with a literal existence and others viewing them as Jungian archetypes or symbols.[38] Even among theistic Wiccans, there are divergent beliefs, and Wicca includes pantheists, monotheists, duotheists, and polytheists.[39] Common to these divergent perspectives, however, is that Wicca's deities are viewed as forms of ancient, pre-Christian divinities by its practitioners.[40]

Duotheism

Most early Wiccan groups adhered to the duotheistic worship of a Horned God and a Mother Goddess, with practitioners typically believing that these had been the ancient deities worshipped by the hunter-gatherers of the Old Stone Age, whose veneration had been passed down in secret right to the present.[38] This theology derived from Egyptologist Margaret Murray's claims about the witch-cult in her book The Witch-Cult in Western Europe published by Oxford University Press in 1921;[41] she claimed that this cult had venerated a Horned God at the time of the Early Modern witch trials, but centuries before it had also worshipped a Mother Goddess.[40] This duotheistic Horned God/Mother Goddess structure was embraced by Gardner – who claimed that it had Stone Age roots – and remains the underlying theological basis to his Gardnerian tradition.[42] Gardner claimed that the names of these deities were to be kept secret within the tradition, although in 1964 they were publicly revealed to be Cernunnos and Aradia; the secret Gardnerian deity names were subsequently changed.[43]

Although different Wiccans attribute different traits to the Horned God, he is most often associated with animals and the natural world, but also with the afterlife, and he is furthermore often viewed as an ideal role model for men.[44] The Mother Goddess has been associated with life, fertility, and the springtime, and has been described as an ideal role model for women.[45] Wicca's duotheism has been compared to the Taoist system of yin and yang.[40]

Other Wiccans have adopted the original Gardnerian God/Goddess duotheistic structure but have adopted deity forms other than that of the Horned God and Mother Goddess.[46] For instance, the God has been interpreted as the Oak King and the Holly King, as well as the Sun God, Son/Lover God, and Vegetation God.[47] He has also been seen in the roles of the Leader of the Wild Hunt and the Lord of Death.[48] The Goddess is often portrayed as a Triple Goddess, thereby being a triadic deity comprising a Maiden goddess, a Mother goddess, and a Crone goddess, each of whom has different associations, namely virginity, fertility, and wisdom.[47][49] Other Wiccan conceptualisations have portrayed her as a Moon Goddess and as a Menstruating Goddess.[47] According to the anthropologist Susan Greenwood, in Wicca the Goddess is "a symbol of self-transformation - she is seen to be constantly changing and a force for change for those who open themselves up to her".[50]

Monotheism and polytheism

Gardner stated that beyond Wicca's two deities was the "Supreme Deity" or "Prime Mover", an entity that was too complex for humans to understand.[51] This belief has been endorsed by other practitioners, who have referred to it as "the Cosmic Logos", "Supreme Cosmic Power", or "Godhead".[51] Gardner envisioned this Supreme Deity as a deist entity who had created the "Under-Gods", among them the God and Goddess, but who was not otherwise involved in the world; alternately, other Wiccans have interpreted such an entity as a pantheistic being, of whom the God and Goddess are facets.[52]

Although Gardner criticised monotheism, citing the Problem of Evil,[51] explicitly monotheistic forms of Wicca developed in the 1960s, when the U.S.-based Church of Wicca developed a theology rooted in the worship of what they described as "one deity, without gender".[53] In the 1970s, Dianic Wiccan groups developed which were devoted to a singular, monotheistic Goddess; this approach was often criticised by members of British Traditional Wiccan groups, who lambasted such Goddess monotheism as an inverted imitation of Christian theology.[54] As in other forms of Wicca, some Goddess monotheists have expressed the view that the Goddess is not an entity with a literal existence, but rather a Jungian archetype.[55]

As well as pantheism and duotheism, many Wiccans accept the concept of polytheism, thereby believing that there are many different deities. Some accept the view espoused by the occultist Dion Fortune that "all gods are one god, and all goddesses are one goddess" – that is that the gods and goddesses of all cultures are, respectively, aspects of one supernal God and Goddess. With this mindset, a Wiccan may regard the Germanic Ēostre, Hindu Kali, and Catholic Virgin Mary each as manifestations of one supreme Goddess and likewise, the Celtic Cernunnos, the ancient Greek Dionysus and the Judeo-Christian Yahweh as aspects of a single, archetypal god. A more strictly polytheistic approach holds the various goddesses and gods to be separate and distinct entities in their own right. The Wiccan writers Janet Farrar and Gavin Bone have postulated that Wicca is becoming more polytheistic as it matures, tending to embrace a more traditionally Pagan worldview.[56] Some Wiccans conceive of deities not as literal personalities but as metaphorical archetypes or thoughtforms, thereby technically allowing them to be atheists.[57] Such a view was purported by the High Priestess Vivianne Crowley, herself a psychologist, who considered the Wiccan deities to be Jungian archetypes that existed within the subconscious that could be evoked in ritual. It was for this reason, she said "The Goddess and God manifest to us in dream and vision".[58] Wiccans often believe that the gods are not perfect and can be argued with.[59]

Many Wiccans also adopt a more explicitly polytheistic or animistic world-view of the universe as being replete with spirit-beings.[60] In many cases these spirits are associated with the natural world, for instance as genius loci, fairies, and elementals.[61] In other cases, such beliefs are more idiosyncratic and atypical; Wiccan Sybil Leek for instance endorsed a belief in angels.[61]

Afterlife

Belief in the afterlife varies among Wiccans and does not occupy a central place within the religion.[62] As the historian Ronald Hutton remarked, "the instinctual position of most [Wiccans] ... seems to be that if one makes the most of the present life, in all respects, then the next life is more or less certainly going to benefit from the process, and so one may as well concentrate on the present".[63] It is nevertheless a common belief among Wiccans that human beings have a spirit or soul that survives bodily death.[62] Understandings of what this soul constitutes vary among different traditions, with the Feri tradition of witchcraft, for instance, having adopted a belief from the Theosophy-inspired Huna movement, Kabbalah, and other sources, that the human being has three souls.[62]

Although not accepted by all Wiccans, a belief in reincarnation is the dominant afterlife belief within Wicca, having been originally espoused by Gardner.[62] Understandings of how the cycle of reincarnation operates differ among practitioners; Wiccan Raymond Buckland for instance insisted that human souls would only incarnate into human bodies, whereas other Wiccans believe that a human soul can incarnate into any life form.[64] There is also a common Wiccan belief that any Wiccans will come to be reincarnated as future Wiccans, an idea originally expressed by Gardner.[64] Gardner also articulated the view that the human soul rested for a period between bodily death and its incarnation, with this resting place commonly being referred to as "The Summerland" among the Wiccan community.[62] This allows many Wiccans to believe that mediums can contact the spirits of the deceased, a belief adopted from Spiritualism.[62]

Magic and spellcraft

Many Wiccans believe in magic, a manipulative force exercised through the practice of "spellcraft".[65] Many Wiccans agree with the definition of magic offered by ceremonial magicians,[66] such as Aleister Crowley, who declared that magic was "the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with will", while another ceremonial magician, MacGregor Mathers stated that it was "the science of the control of the secret forces of nature".[66] Many Wiccans believe magic to be a law of nature, as yet misunderstood or disregarded by contemporary science,[66] and as such they do not view it as being supernatural, but a part of what Leo Martello calls the "super powers that reside in the natural".[67] Some Wiccans believe that magic is simply making full use of the five senses to achieve surprising results,[67] whilst other Wiccans do not claim to know how magic works, merely believing that it does because they have observed it to be so.[68]

During ritual practices, which are often staged in a sacred circle, Wiccans cast spells or "workings" intended to bring about real changes in the physical world. Common Wiccan spells include those used for healing, for protection, fertility, or to banish negative influences.[69] Many early Wiccans, such as Alex Sanders, Sybil Leek and Alex Winfield, referred to their own magic as "white magic", which contrasted with "black magic", which they associated with evil and Satanism. Sanders also used the similar terminology of "left-hand path" to describe malevolent magic, and "right-hand path" to describe magic performed with good intentions;[70] terminology that had originated with the occultist Helena Blavatsky in the 19th century. Some modern Wiccans, however, have stopped using the white/black magic and left/right-hand-path dichotomies, arguing for instance that the colour black should not necessarily have any associations with evil.[71]

Scholars of religion Rodney Stark and William Bainbridge claimed in 1985 that Wicca had "reacted to secularisation by a headlong plunge back into magic" and that it was a reactionary religion which would soon die out. This view was heavily criticised in 1999 by the historian Ronald Hutton who claimed that the evidence displayed the very opposite: that "a large number [of Wiccans] were in jobs at the cutting edge [of scientific culture], such as computer technology".[72]

Witchcraft

Identification as a witch can[…] provide a link to those persecuted and executed in the Great Witch Hunt, which can then be remembered as a holocaust against women, a repackaging of history that implies conscious victimization and the appropriation of 'holocaust' as a badge of honour — 'gendercide rather than genocide'. An elective identification with the image of the witch during the time of the persecutions is commonly regarded as part of the reclamation of female power, a myth that is used by modern feminist witches as an aid in their struggle for freedom from patriarchal oppression.

— Religious studies scholar Joanne Pearson[73]

Historian Wouter Hanegraaff noted that the Wiccan view of witchcraft was "an outgrowth of Romantic (semi)scholarship", especially the 'witch cult' theory.[74] It proposed that historical alleged witches were actually followers of a surviving pagan religion, and that accusations of infanticide, cannibalism, Satanism etc were either made up by the Inquisition or were misunderstandings of pagan rites.[75] This theory that accused witches were actually pagans has now been disproven.[22] Nevertheless, Gardner and other founders of Wicca believed the theory was true, and saw the witch as a "positive antitype which derives much of its symbolic force from its implicit criticism of dominant Judaeo-Christian and Enlightenment values".[75]

Pearson suggested that Wiccans "identify with the witch because she is imagined as powerful - she can make people sleep for one hundred years, she can see the future, she can curse and kill as well as heal[…] and of course, she can turn people into frogs!"[76] Pearson says that Wicca "provides a framework in which the image of oneself as a witch can be explored and brought into a modern context".[77] Identifying as a witch also enables Wiccans to link themselves with those persecuted in the witch trials of the Early Modern period, often referred to by Wiccans as "the Burning Times".[78] Various practitioners have claimed that as many as nine million people were executed as witches in the Early Modern period, thus drawing comparisons with the killing of six million Jews in the Holocaust and presenting themselves, as modern witches, as "persecuted minorities".[76]

Morality

Bide the Wiccan laws ye must, in perfect love and perfect trust ... Mind the Threefold Law ye should – three times bad and three times good ... Eight words the Wiccan Rede fulfill – an it harm none, do what ye will.

Wicca has been characterised as a life-affirming religion.[80] Practitioners typically present themselves as "a positive force against the powers of destruction which threaten the world".[81] There exists no dogmatic moral or ethical code followed universally by Wiccans of all traditions, however a majority follow a code known as the Wiccan Rede, which states "an it harm none, do what ye will". This is usually interpreted as a declaration of the freedom to act, along with the necessity of taking responsibility for what follows from one's actions and minimising harm to oneself and others.[82]

Another common element of Wiccan morality is the Law of Threefold Return which holds that whatever benevolent or malevolent actions a person performs will return to that person with triple force, or with equal force on each of the three levels of body, mind, and spirit,[83] similar to the eastern idea of karma. The Wiccan Rede was most likely introduced into Wicca by Gerald Gardner and formalised publicly by Doreen Valiente, one of his High Priestesses. The Threefold Law was an interpretation of Wiccan ideas and ritual, made by Monique Wilson[84] and further popularized by Raymond Buckland, in his books on Wicca.[85]

There is some disagreement among Wiccans as to what the Law of Threefold Return (or Law of Three) actually means, or even whether such a law exists at all. As just one example, McKenzie Sage Wright discusses this in her HubPages artlcle, Ethics in Wicca: The Threefold Law.

Many Wiccans also seek to cultivate a set of eight virtues mentioned in Doreen Valiente's Charge of the Goddess,[86] these being mirth, reverence, honour, humility, strength, beauty, power, and compassion. In Valiente's poem, they are ordered in pairs of complementary opposites, reflecting a dualism that is common throughout Wiccan philosophy. Some lineaged Wiccans also observe a set of Wiccan Laws, commonly called the Craft Laws or Ardanes, 30 of which exist in the Gardnerian tradition and 161 of which are in the Alexandrian tradition. Valiente, one of Gardner's original High Priestesses, argued that the first thirty of these rules were most likely invented by Gerald Gardner himself in mock-archaic language as the by-product of inner conflict within his Bricket Wood coven.[87][72]

In British Traditional Wicca, "sex complementarity is a basic and fundamental working principle", with men and women being seen as a necessary presence to balance each other out.[88] This may have derived from Gardner's interpretation of Murray's claim that the ancient witch-cult was a fertility religion.[88] Thus, many practitioners of British Traditional Wicca have argued that gay men and women are not capable of correctly working magic without mixed-sex pairings.[89]

Although Gerald Gardner initially demonstrated an aversion to homosexuality, claiming that it brought down "the curse of the goddess",[90] it is now generally accepted in all traditions of Wicca, with groups such as the Minoan Brotherhood openly basing their philosophy upon it.[91] Nonetheless, a variety of viewpoints exist in Wicca around this point, with some covens adhering to a hetero-normative viewpoint. Carly B. Floyd of Illinois Wesleyan University has published an informative white paper on this subject: Mother Goddesses and Subversive Witches: Competing Narratives of Gender Essentialism, Heteronormativity, Feminism, and Queerness in Wiccan Theology and Ritual.

The scholar of religion Joanne Pearson noted that in her experience, most Wiccans take a "realistic view of living in the real world" replete with its many problems and do not claim that the gods "have all the answers" to these.[92] She suggested that Wiccans do not claim to seek perfection but instead "wholeness" or "completeness", which includes an acceptance of traits like anger, weakness, and pain.[93] She contrasted the Wiccan acceptance of an "interplay between light and dark" against the New Age focus on "white light".[94] Similarly, the scholar of religion Geoffrey Samuel noted that Wiccans devote "a perhaps surprising amount of attention to darkness and death".[80]

Many Wiccans are involved in environmentalist campaigns.[95]

Five elements

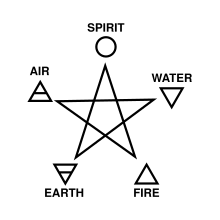

Many traditions hold a belief in the five classical elements, although they are seen as symbolic representations of the phases of matter. These five elements are invoked during many magical rituals, notably when consecrating a magic circle. The five elements are air, fire, water, earth, and aether (or spirit), where aether unites the other four elements.[96] Various analogies have been devised to explain the concept of the five elements; for instance, the Wiccan Ann-Marie Gallagher used that of a tree, which is composed of earth (with the soil and plant matter), water (sap and moisture), fire (through photosynthesis) and air (the formation of oxygen from carbon dioxide), all of which are believed to be united through spirit.[97]

Traditionally in the Gardnerian Craft, each element has been associated with a cardinal point of the compass; air with east, fire with south, water with west, earth with north, and the spirit with centre.[98] However, some Wiccans, such as Frederic Lamond, have claimed that the set cardinal points are only those applicable to the geography of southern England, where Wicca evolved, and that Wiccans should determine which directions best suit each element in their region. For instance, those living on the east coast of North America should invoke water in the east and not the west because the colossal body of water, the Atlantic ocean, is to their east.[99] Other Craft groups have associated the elements with different cardinal points, for instance Robert Cochrane's Clan of Tubal Cain associated earth with south, fire with east, water with west and air with north,[100] and each of which were controlled over by a different deity who were seen as children of the primary Horned God and Goddess. The five elements are symbolised by the five points of the pentagram, the most-used symbol of Wicca.[101]

Practices

The Wiccan high priestess and journalist Margot Adler stated that Wiccan rituals were not "dry, formalised, repetitive experiences", but performed with the intent of inducing a religious experience in the participants, thereby altering their consciousness.[102] She noted that many Wiccans remain skeptical about the existence of the supernatural but remain involved in Wicca because of its ritual experiences: she quoted one as saying that "I love myth, dream, visionary art. The Craft is a place where all of these things fit together – beauty, pageantry, music, dance, song, dream".[103] The Wiccan practitioner and historian Aidan Kelly claimed that the practices and experiences within Wicca were more important than the beliefs, stating: "it's a religion of ritual rather than theology. The ritual is first; the myth is second".[104] Similarly, Adler stated that Wicca permits "total skepticism about even its own methods, myths and rituals".[105]

The anthropologist Susan Greenwood characterised Wiccan rituals as "a form of resistance to mainstream culture".[89] She saw these rituals as "a healing space away from the ills of the wider culture", one in which female practitioners can "redefine and empower themselves".[106]

Wiccan rituals usually take place in private.[107] The Reclaiming tradition has utilised its rituals for political purposes.[81]

Practice in Wicca (including, as an example, matters such as the varying attributions of the elements to different directions discussed in the preceding section) varies widely due to the Craft's emphasis on individual expression in one's spiritual/magical path.[108]

Ritual practices

Many rituals within Wicca are used when celebrating the Sabbats, worshipping the deities, and working magic. Often these take place on a full moon, or in some cases a new moon, which is known as an Esbat. In typical rites, the coven or solitary assembles inside a ritually cast and purified magic circle. Casting the circle may involve the invocation of the "Guardians" of the cardinal points, alongside their respective classical elements; air, fire, water, and earth. Once the circle is cast, a seasonal ritual may be performed, prayers to the God and Goddess are said, and spells are sometimes worked; these may include various forms of 'raising energy', including raising a cone of power to send healing or other magic to persons outside of the sacred space.[citation needed]

In constructing his ritual system, Gardner drew upon older forms of ceremonial magic, in particular, those found in the writings of Aleister Crowley.[109]

The classical ritual scheme in British Traditional Wicca traditions is:[110]

- Purification of the sacred space and the participants

- Casting the circle

- Calling of the elemental quarters

- Cone of power

- Drawing down the Gods

- Spellcasting

- Great Rite

- Wine, cakes, chanting, dancing, games

- Farewell to the quarters and participants

These rites often include a special set of magical tools. These usually include a knife called an athame, a wand, a pentacle and a chalice, but other tools include a broomstick known as a besom, a cauldron, candles, incense and a curved blade known as a boline. An altar is usually present in the circle, on which ritual tools are placed and representations of the God and the Goddess may be displayed.[111] Before entering the circle, some traditions fast for the day, and/or ritually bathe. After a ritual has finished, the God, Goddess, and Guardians are thanked, the directions are dismissed and the circle is closed.[112]

A central aspect of Wicca (particularly in Gardnerian and Alexandrian Wicca), often sensationalised by the media is the traditional practice of working in the nude, also known as skyclad. Although no longer widely used, this practice seemingly derives from a line in Aradia, Charles Leland's supposed record of Italian witchcraft.[113] Many Wiccans believe that performing rituals skyclad allows "power" to flow from the body in a manner unimpeded by clothes.[114] Some also note that it removes signs of social rank and differentiation and thus encourages unity among the practitioners.[114] Some Wiccans seek legitimacy for the practice by stating that various ancient societies performed their rituals while nude.[114]

One of Wicca's best known liturgical texts is "The Charge of the Goddess".[48] The most commonly used version used by Wiccans today is the rescension of Doreen Valiente,[48] who developed it from Gardner's version. Gardner's wording of the original "Charge" added extracts from Aleister Crowley's work, including The Book of the Law, (especially from Ch 1, spoken by Nuit, the Star Goddess) thus linking modern Wicca irrevocably to the principles of Thelema. Valiente rewrote Gardner's version in verse, keeping the material derived from Aradia, but removing the material from Crowley.[115]

Sex magic

Other traditions wear robes with cords tied around the waist or even normal street clothes. In certain traditions, ritualised sex magic is performed in the form of the Great Rite, whereby a High Priest and High Priestess invoke the God and Goddess to possess them before performing sexual intercourse to raise magical energy for use in spellwork. In nearly all cases it is instead performed "in token", thereby merely symbolically, using the athame to symbolise the penis and the chalice to symbolise the womb.[116]

Gerald Gardner, the man many consider the father of Wicca, believed strongly in sex magic. Much of Gardner's witch practice centered around the power of sex and its liberation, and that one of the most important aspects of the neo-Pagan revival has been its ties, not just to sexual liberation, but also to feminism and women's liberation.[117]

For some Wiccans, the ritual space is a "space of resistance, in which the sexual morals of Christianity and patriarchy can be subverted", and for this reason they have adopted techniques from the BDSM subculture into their rituals.[118]

Publicly, many Wiccan groups have tended to excise the role of sex magic from their image.[119] This has served both to escape the tabloid sensationalism that has targeted the religion since the 1950s and the concerns surrounding the Satanic ritual abuse hysteria in the 1980s and 1990s.[119]

Some Wiccan Traditions substitute a Communion style rite in honor of the God and Goddess rather than the symbolic Great Rite in their Esbat ritual.

Wheel of the Year

Wiccans celebrate several seasonal festivals of the year, commonly known as Sabbats. Collectively, these occasions are termed the Wheel of the Year.[86] Most Wiccans celebrate a set of eight of these Sabbats; however, other groups such as those associated with the Clan of Tubal Cain only follow four. In the rare case of the Ros an Bucca group from Cornwall, only six are adhered to.[120] The four Sabbats that are common to all British derived groups are the cross-quarter days, sometimes referred to as Greater Sabbats. The names of these festivals are in some cases taken from the Old Irish fire festivals and the Welsh God Mabon,[121] though in most traditional Wiccan covens the only commonality with the Celtic festival is the name. Gardner himself made use of the English names of these holidays, stating that "the four great Sabbats are Candlemas [sic], May Eve, Lammas, and Halloween; the equinoxes and solstices are celebrated also".[122] In the Egyptologist Margaret Murray's The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921) and The God of the Witches (1933), in which she dealt with what she believed had been a historical Witch-Cult, she stated that the four main festivals had survived Christianisation and had been celebrated in the Pagan Witchcraft religion. Subsequently, when Wicca was first developing in the 1930s through to the 1960s, many of the early groups, such as Robert Cochrane's Clan of Tubal Cain and Gerald Gardner's Bricket Wood coven adopted the commemoration of these four Sabbats as described by Murray.[citation needed]

The other four festivals commemorated by many Wiccans are known as Lesser Sabbats. They are the solstices and the equinoxes, and they were only adopted in 1958 by members of the Bricket Wood coven,[123] before they were subsequently adopted by other followers of the Gardnerian tradition. They were eventually adopted by followers of other traditions like Alexandrian Wicca and the Dianic tradition. The names of these holidays that are commonly used today are often taken from Germanic pagan holidays. However, the festivals are not reconstructive in nature nor do they often resemble their historical counterparts, instead, they exhibit a form of universalism. The rituals that are observed may display cultural influences from the holidays from which they take their names as well as influences from other unrelated cultures.[124]

| Sabbat | Northern Hemisphere | Southern Hemisphere | Origin of Name | Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samhain | 31 October to 1 November | 30 April to 1 May | Celtic polytheism | Death and the ancestors |

| Yuletide | 21 or 22 December | 21 June | Germanic paganism | Winter solstice and the rebirth of the Sun |

| Imbolc, a.k.a. Candlemas | 1 or 2 February | 1 August | Celtic polytheism | First signs of spring |

| Ostara | 21 or 22 March | 21 or 22 September | Germanic paganism | Vernal equinox and the beginning of spring |

| Beltane, a.k.a. May Eve or May Day | 30 April to 1 May | 31 October to 1 November | Celtic polytheism | The full flowering of spring; fairy folk[125] |

| Litha | 21 or 22 June | 21 December | Early Germanic calendar | Summer solstice |

| Lughnasadh, a.k.a. Lammas | 31 July or 1 August | 1 February | Celtic polytheism | First fruits |

| Mabon, a.k.a. Modron[126] | 21 or 22 September | 21 March | No historical pagan equivalent. | Autumnal equinox; the harvest of grain |

Rites of passage

Various rites of passage can be found within Wicca. Perhaps the most significant of these is an initiation ritual, through which somebody joins the Craft and becomes a Wiccan. In British Traditional Wiccan (BTW) traditions, there is a line of initiatory descent that goes back to Gerald Gardner, and from him is said to go back to the New Forest coven; however, the existence of this coven remains unproven.[127] Gardner himself claimed that there was a traditional length of "a year and a day" between when a person began studying the Craft and when they were initiated, although he frequently broke this rule with initiates.

In BTW, initiation only accepts someone into the first degree. To proceed to the second degree, an initiate has to go through another ceremony, in which they name and describe the uses of the ritual tools and implements. It is also at this ceremony that they are given their craft name. By holding the rank of second degree, a BTW is considered capable of initiating others into the Craft, or founding their own semi-autonomous covens. The third degree is the highest in BTW, and it involves the participation of the Great Rite, either actual or symbolically, and in some cases ritual flagellation, which is a rite often dispensed with due to its sado-masochistic overtones. By holding this rank, an initiate is considered capable of forming covens that are entirely autonomous of their parent coven.[128][129]

According to new-age religious scholar James R. Lewis, in his book Witchcraft today: an encyclopaedia of Wiccan and neopagan traditions, a high priestess becomes a queen when she has successfully hived off her first new coven under a new third-degree high priestess (in the orthodox Gardnerian system). She then becomes eligible to wear the "moon crown". The sequence of high priestess and queens traced back to Gerald Gardner is known as a lineage, and every orthodox Gardnerian High Priestess has a set of "lineage papers" proving the authenticity of her status.[130]

This three-tier degree system following initiation is largely unique to BTW, and traditions heavily based upon it. The Cochranian tradition, which is not BTW, but based upon the teachings of Robert Cochrane, does not have the three degrees of initiation, merely having the stages of novice and initiate.

Some solitary Wiccans also perform self-initiation rituals, to dedicate themselves to becoming a Wiccan. The first of these to be published was in Paul Huson's Mastering Witchcraft (1970), and unusually involved recitation of the Lord's Prayer backwards as a symbol of defiance against the historical Witch Hunt.[131] Subsequent, more overtly pagan self-initiation rituals have since been published in books designed for solitary Wiccans by authors like Doreen Valiente, Scott Cunningham and Silver RavenWolf.

Handfasting is another celebration held by Wiccans, and is the commonly used term for their weddings. Some Wiccans observe the practice of a trial marriage for a year and a day, which some traditions hold should be contracted on the Sabbat of Lughnasadh, as this was the traditional time for trial, "Telltown marriages" among the Irish. A common marriage vow in Wicca is "for as long as love lasts" instead of the traditional Christian "till death do us part".[132] The first known Wiccan wedding ceremony took part in 1960 amongst the Bricket Wood coven, between Frederic Lamond and his first wife, Gillian.[72]

Infants in Wiccan families may be involved in a ritual called a Wiccaning, which is analogous to a Christening. The purpose of this is to present the infant to the God and Goddess for protection. Parents are advised to "give [their] children the gift of Wicca" in a manner suitable to their age. In accordance with the importance put on free will in Wicca, the child is not expected or required to adhere to Wicca or other forms of paganism should they not wish to do so when they reach adulthood.[133]

Book of Shadows

In Wicca, there is no set sacred text such as the Christian Bible, Jewish Tanakh, or Islamic Quran, although there are certain scriptures and texts that various traditions hold to be important and influence their beliefs and practices. Gerald Gardner used a book containing many different texts in his covens, known as the Book of Shadows (among other names), which he would frequently add to and adapt. In his Book of Shadows, there are texts taken from various sources, including Charles Godfrey Leland's Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches (1899) and the works of 19th–20th century occultist Aleister Crowley, whom Gardner knew personally. Also in the Book are examples of poetry largely composed by Gardner and his High Priestess Doreen Valiente, the most notable of which is the Charge of the Goddess.

The Book of Shadows is not a Bible or Quran. It is a personal cookbook of spells that have worked for the owner. I am giving you mine to copy to get you started: as you gain experience discard those spells that don't work for you and substitute those that you have thought of yourselves.

Gerald Gardner to his followers[134]

Similar in use to the grimoires of ceremonial magicians,[135] the Book contained instructions for how to perform rituals and spells, as well as religious poetry and chants like Eko Eko Azarak to use in those rituals. Gardner's original intention was that every copy of the book would be different because a student would copy from their initiators, but changing things which they felt to be personally ineffective, however amongst many Gardnerian Witches today, particularly in the United States, all copies of the Book are kept identical to the version that the High Priestess Monique Wilson copied from Gardner, with nothing being altered. The Book of Shadows was originally meant to be kept a secret from non-initiates into BTW, but parts of the Book have been published by authors including Charles Cardell, Lady Sheba, Janet Farrar and Stewart Farrar.[110][136]

Symbolism

The pentacle is a symbol commonly used by Wiccans.[93] Wiccans often understand the pentacle's five points as representing each of the five elements: earth, air, fire, water, and aether/spirit.[93] It is also regarded as a symbol of the human, with the five points representing the head, arms, and legs.[93]

Structure

There is no overarching organisational structure to Wicca.[137] In Wicca, all practitioners are considered to be priests and priestesses.[59] Wicca generally requires a ritual of initiation.[138]

Traditions

In the 1950s through to the 1970s, when the Wiccan movement was largely confined to lineaged groups such as Gardnerian Wicca and Alexandrian Wicca, a "tradition" usually implied the transfer of a lineage by initiation. However, with the rise of more and more such groups, often being founded by those with no previous initiatory lineage, the term came to be a synonym for a religious denomination within Wicca. Scholars of religion tend to treat Wicca as a religion with denominations that differ on some important points but share core beliefs, much like Christianity and its many denominations.[139] There are many such traditions[140][141] and there are also many solitary practitioners who do not align themselves with any particular lineage, working alone. Some covens have formed but who do not follow any particular tradition, instead choosing their influences and practices eclectically.

Those traditions which trace a line of initiatory descent back to Gerald Gardner include Gardnerian Wicca, Alexandrian Wicca and the Algard tradition; because of their joint history, they are often referred to as British Traditional Wicca, particularly in North America. Other traditions trace their origins to different figures, even if their beliefs and practices have been influenced to a greater or lesser extent by Gardner. These include Cochrane's Craft and the 1734 Tradition, both of which trace their origins to Robert Cochrane; Feri, which traces itself back to Victor Anderson and Gwydion Pendderwen; and Dianic Wicca, whose followers often trace their influences back to Zsuzsanna Budapest. Some of these groups prefer to refer to themselves as Witches, thereby distinguishing themselves from the BTW traditions, who more typically use the term Wiccan (see Etymology).[citation needed] During the 1980s, Viviane Crowley, an initiate of both the Gardnerian and Alexandrian traditions, merged the two.[142]

Pearson noted that "Wicca has evolved and, at times, mutated quite dramatically into completely different forms".[143] Wicca has also been "customized" to the various national contexts into which it has been introduced; for instance, in Ireland, the veneration of ancient Irish deities has been incorporated into Wicca.[144]

Covens

Lineaged Wicca is organised into covens of initiated priests and priestesses. Covens are autonomous and are generally headed by a High Priest and a High Priestess working in partnership, being a couple who have each been through their first, second, and third degrees of initiation. Occasionally the leaders of a coven are only second-degree initiates, in which case they come under the rule of the parent coven. Initiation and training of new priesthood is most often performed within a coven environment, but this is not a necessity, and a few initiated Wiccans are unaffiliated with any coven.[145] Most covens would not admit members under the age of 18.[146] They often do not advertise their existence, and when they do, do so through pagan magazines.[147] Some organise courses and workshops through which prospective members can come along and be assessed.[148]

A commonly quoted Wiccan tradition holds that the ideal number of members for a coven is thirteen, though this is not held as a hard-and-fast rule.[145] Indeed, many U.S. covens are far smaller, though the membership may be augmented by unaffiliated Wiccans at "open" rituals.[149] Pearson noted that covens typically contained between five and ten initiates.[150] They generally avoid mass recruitment due to the feasibility of finding spaces large enough to bring together greater numbers for rituals and because larger numbers inhibit the sense of intimacy and trust that covens utilise.[150]

Some covens are short-lived, but others have survived for many years.[150] Covens in the Reclaiming tradition are often single-sex and non-hierarchical in structure.[151] Coven members who leave their original group to form another, separate coven are described as having "hived off" in Wicca.[150]

Initiation into a coven is traditionally preceded by an apprenticeship period of a year and a day.[152] A course of study may be set during this period. In some covens a "dedication" ceremony may be performed during this period, some time before the initiation proper, allowing the person to attend certain rituals on a probationary basis. Some solitary Wiccans also choose to study for a year and a day before their self-dedication to the religion.[153]

Various high priestesses and high priests have reported being "put on a pedestal" by new initiates, only to have those students later "kick away" the pedestal as they develop their own knowledge and experience of Wicca.[154] Within a coven, different members may be respected for having particular knowledge of specific areas, such as the Qabalah, astrology, or the Tarot.[59]

Based on her experience among British Traditional Wiccans in the UK, Pearson stated that the length of time between becoming a first-degree initiate and a second was "typically two to five years".[138] Some practitioners nevertheless chose to remain as first-degree initiates rather than proceed to the higher degrees.[138]

Eclectic Wicca

A large number of Wiccans do not exclusively follow any single tradition or even are initiated. These eclectic Wiccans each create their own syncretic spiritual paths by adopting and reinventing the beliefs and rituals of a variety of religious traditions connected to Wicca and broader paganism.

While the origins of modern Wiccan practice lie in covenantal activity of a select few initiates in established lineages, eclectic Wiccans are more often than not solitary practitioners uninitiated in any tradition. A widening public appetite, especially in the United States, made traditional initiation unable to satisfy demand for involvement in Wicca. Since the 1970s, larger, more informal, often publicly advertised camps and workshops began to take place.[155] This less formal but more accessible form of Wicca proved successful. Eclectic Wicca is the most popular variety of Wicca in America[156] and eclectics now significantly outnumber lineaged Wiccans.

Eclectic Wicca is not necessarily the complete abandonment of tradition. Eclectic practitioners may follow their own individual ideas and ritual practices, while still drawing on one or more religious or philosophical paths. Eclectic approaches to Wicca often draw on Earth religion and ancient Egyptian, Greek, Saxon, Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, Asian, Jewish, and Polynesian traditions.[157]

In contrast to the British Traditional Wiccans, Reclaiming Wiccans, and various eclectic Wiccans, the sociologist Douglas Ezzy argued that there existed a "Popularized Witchcraft" that was "driven primarily by consumerist marketing and is represented by movies, television shows, commercial magazines, and consumer goods".[158] Books and magazines in this vein were targeted largely at young girls and included spells for attracting or repelling boyfriends, money spells, and home protection spells.[159] He termed this "New Age Witchcraft",[160] and compared individuals involved in this to the participants in the New Age.[158]

History

Origins, 1921–1935

Wicca originated in the early decades of the twentieth century among those esoterically inclined Britons who wanted to resurrect the faith of their ancient forebears, and arose to public attention in the 1950s and 1960s, largely due to a small band of dedicated followers who were insistent on presenting their faith to what at times was a very hostile world. From these humble beginnings, this radical religion spread to the United States, where it found a comfortable bedfellow in the form of the 1960s counter-culture and came to be championed by those sectors of the women's and gay liberation movements which were seeking a spiritual escape from Christian hegemony.

— Religious studies scholar Ethan Doyle White[161]

Wicca was founded in England between 1921 and 1950,[162] representing what the historian Ronald Hutton called "the only full-formed religion which England can be said to have given the world".[163] Characterised as an "invented tradition" by scholars,[164] Wicca was created from the patchwork adoption of various older elements, many taken from pre-existing religious and esoteric movements.[165] Pearson characterised it as having arisen "from the cultural impulses of the fin de siècle".[166]

Wicca took as its basis the witch-cult hypothesis. This was the idea that those persecuted as witches in early modern Europe were actually followers of a surviving pagan religion; not Satanists as the persecutors claimed, nor innocent people who confessed under threat of torture, as had long been the historical consensus.[162][167] The 'Father of Wicca', Gerald Gardner, claimed his religion was a survival of this European 'witch-cult'.[168] The 'witch-cult' theory had been first expressed by the German Professor Karl Ernest Jarcke in 1828, before being endorsed by German Franz Josef Mone and then the French historian Jules Michelet.[169] In the late 19th century, it was then adopted by two Americans, Matilda Joslyn Gage and Charles Leland, the latter of whom promoted a variant of it in his 1899 book, Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches.[170] The theory's most notable advocate was the English Egyptologist Margaret Murray, who promoted it in a series of books – most notably 1921's The Witch-Cult in Western Europe and 1933's The God of the Witches.[171][167]

Almost all of Murray's peers regarded the witch-cult theory as incorrect and based on poor scholarship. However, Murray was invited to write the entry on "witchcraft" for the 1929 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, which was reprinted for decades and became so influential that, according to folklorist Jacqueline Simpson, Murray's ideas became "so entrenched in popular culture that they will probably never be uprooted".[172] Simpson noted that the only contemporary member of the Folklore Society who took Murray's theory seriously was Gerald Gardner, who used it as the basis for Wicca.[172] Murray's books were the sources of many well-known motifs which have often been incorporated into Wicca. The idea that covens should have 13 members was developed by Murray, based on a single witness statement from one of the witch trials, as was her assertion that covens met on the four cross-quarter days.[172] Murray was very interested in ascribing naturalistic or religious ceremonial explanations to some of the more fantastic descriptions found in witch trial testimony. For example, many of the confessions included the idea that Satan was personally present at coven meetings. Murray interpreted this as a witch priest wearing horns and animal skins, and a pair of forked boots to represent his authority or rank. Most mainstream folklorists, on the other hand, have argued that the entire scenario was always fictitious and does not require a naturalistic explanation, but Gardner enthusiastically adopted many of Murray's explanations into his own tradition.[172] The witch-cult theory was "the historical narrative around which Wicca built itself", with the early Wiccans claiming to be the survivors of this ancient pagan religion.[173]

The 'witch-cult' theory has since been disproven by further historical research,[22] but it is still common for Wiccans to claim solidarity with witch trial victims.[174] The notion that Wiccan traditions and rituals have survived from ancient times is contested by most recent researchers, who say that Wicca is a 20th-century creation which combines elements of freemasonry and 19th-century occultism.[175] In his 1999 book The Triumph of the Moon, English historian Ronald Hutton researched the Wiccan claim that ancient pagan customs have survived into modern times after being Christianised in medieval times as folk practices. Hutton found that most of the folk customs which are claimed to have pagan roots (such as the Maypole dance) actually date from the Middle Ages. He concluded that the idea that medieval revels were pagan in origin is a legacy of the Protestant Reformation.[72][176] Hutton noted that Wicca predates the modern New Age movement and also differs markedly in its general philosophy.[72]

Other influences upon early Wicca included various Western esoteric traditions and practices, among them ceremonial magic, Aleister Crowley and his religion of Thelema, Freemasonry, Spiritualism, and Theosophy.[177] To a lesser extent, Wicca also drew upon folk magic and the practices of cunning folk.[178] It was further influenced both by scholarly works on folkloristics, particularly James Frazer's The Golden Bough, as well as romanticist writings like Robert Graves' The White Goddess, and pre-existing modern pagan groups such as the Order of Woodcraft Chivalry and Druidism.[179]

Early development, 1936–1959

It was during the 1930s that the first evidence appears for the practice of a neopagan 'Witchcraft' religion[180] (what would be recognisable now as Wicca) in England. It seems that several groups around the country, in such places as Norfolk,[181] Cheshire[182] and the New Forest had set themselves up after being inspired by Murray's writings about the "Witch-Cult".

The history of Wicca starts with Gerald Gardner (the "Father of Wicca") in the mid-20th century. Gardner was a retired British civil servant and amateur anthropologist, with a broad familiarity in paganism and occultism. He claimed to have been initiated into a witches' coven in New Forest, Hampshire, in the late 1930s. Intent on perpetuating this craft, Gardner founded the Bricket Wood coven with his wife Donna in the 1940s, after buying the Naturist Fiveacres Country Club.[183] Much of the coven's early membership was drawn from the club's members[184] and its meetings were held within the club grounds.[185][186] Many notable figures of early Wicca were direct initiates of this coven, including Dafo, Doreen Valiente, Jack Bracelin, Frederic Lamond, Dayonis, Eleanor Bone, and Lois Bourne.

The Witchcraft religion began to grow in 1951, with the repeal of the Witchcraft Act 1735, after which Gerald Gardner and then others such as Charles Cardell and Cecil Williamson began publicising their own versions of the Craft. Gardner and others never used the term "Wicca" as a religious identifier, simply referring to the "witch cult", "witchcraft", and the "Old Religion". However, Gardner did refer to witches as "the Wica".[187] During the 1960s, the name of the religion normalised to "Wicca".[188] Gardner's tradition, later termed Gardnerianism, soon became the dominant form in England and spread to other parts of the British Isles.

Adaptation and spread, 1960–present

Following Gardner's death in 1964, the Craft continued to grow unabated despite sensationalism and negative portrayals in British tabloids, with new traditions being propagated by figures like Robert Cochrane, Sybil Leek, and most importantly Alex Sanders, whose Alexandrian Wicca, which was predominantly based upon Gardnerian Wicca, albeit with an emphasis placed on ceremonial magic, spread quickly and gained much media attention. Around this time, the term "Wicca" began to be commonly adopted over "Witchcraft" and the faith was exported to countries like Australia and the United States.[citation needed]

During the 1970s, a new generation joined Wicca who had been influenced by the counterculture of the 1960s.[189] Many brought environmentalist ideas with them into the movement, as reflected by the formation of groups like the UK-based Pagans Against Nukes.[189] In the U.S., Victor Anderson, Cora Anderson, and Gwydion Pendderwen established the Feri Tradition.[190]

It was in the United States and in Australia that new, home-grown traditions, sometimes based upon earlier, regional folk-magical traditions and often mixed with the basic structure of Gardnerian Wicca, began to develop, including Victor Anderson's Feri Tradition, Joseph Wilson's 1734 Tradition, Aidan Kelly's New Reformed Orthodox Order of the Golden Dawn, and eventually Zsuzsanna Budapest's Dianic Wicca, each of which emphasised different aspects of the faith.[191] It was also around this time that books teaching people how to become Witches themselves without formal initiation or training began to emerge, among them Paul Huson's Mastering Witchcraft (1970) and Lady Sheba's Book of Shadows (1971). Similar books continued to be published throughout the 1980s and 1990s, fuelled by the writings of such authors as Doreen Valiente, Janet Farrar, Stewart Farrar, and Scott Cunningham, who popularised the idea of self-initiation into the Craft. Among witches in Canada, anthropologist Heather Botting (née Harden) of the University of Victoria was the first recognized Wiccan chaplain of a public university.[192] She is the original high priestess of Coven Celeste.[193]

In the 1990s, amid ever-rising numbers of self-initiates, the popular media began to explore "witchcraft" in fictional films like The Craft (1996) and television series like Charmed (1998–2006), introducing numbers of young people to the idea of religious witchcraft. This growing demographic was soon catered to through the Internet and by authors like Silver RavenWolf, much to the criticism of traditional Wiccan groups and individuals. In response to the way that Wicca was increasingly portrayed as trendy, eclectic, and influenced by the New Age movement, many Witches turned to the pre-Gardnerian origins of the Craft, and to the traditions of his rivals like Cardell and Cochrane, describing themselves as following "traditional witchcraft". Groups within this Traditional Witchcraft revival included Andrew Chumbley's Cultus Sabbati and the Cornish Ros an Bucca coven.[citation needed]

Demographics

Originating in Britain, Wicca then spread to North America, Australasia, continental Europe, and South Africa.[143]

The actual number of Wiccans worldwide is unknown, and it has been noted that it is more difficult to establish the numbers of members of Neopagan faiths than many other religions due to their disorganised structure.[194] However, Adherents.com, an independent website which specialises in collecting estimates of world religions, cites over thirty sources with estimates of numbers of Wiccans (principally from the US and the UK). From this, they developed a median estimate of 800,000 members.[195] As of 2016, Doyle White suggested that there were "hundreds of thousands of practising Wiccans around the globe".[161]

In 1998, the Wiccan high priestess and academic psychologist Vivianne Crowley suggested that Wicca had been less successful in propagating in countries whose populations were primarily Roman Catholic. She suggested that this might be because Wicca's emphasis on a female divinity was more novel to people raised in Protestant-dominant backgrounds.[20] On the basis of her experience, Pearson concurred that this was broadly true.[196]

Wicca has been described as a non-proselytizing religion.[197] In 1998, Pearson noted that there were very few individuals who had grown up as Wiccans although increasing numbers of Wiccan adults were themselves, parents.[198] Many Wiccan parents did not refer to their children as also being Wiccan, believing it important that the latter are allowed to make their own choices about their religious identity when they are old enough.[198] From her fieldwork among members of the Reclaiming tradition in California during 1980-90, the anthropologist Jone Salomonsen found that many described joining the movement following "an extraordinary experience of revelation".[199]

Based on their analysis of internet trends, the sociologists of religion Douglas Ezzy and Helen Berger argued that, by 2009, the "phenomenal growth" that Wicca has experienced in preceding years had slowed.[200]

Europe

[The average Wiccan is] a man in his forties, or a woman in her thirties, Caucasian, reasonably well educated, not earning much but probably not too concerned about material things, someone that demographers would call lower middle class.

Leo Ruickbie (2004)[201]

From her 1996 survey of British Wiccans, Pearson found that most Wiccans were aged between 25 and 45, with the average age being around 35.[146] She noted that as the Wiccan community aged, so the proportion of older practitioners would increase.[146] She found roughly equal proportions of men and women,[202] and found that 62% were from Protestant backgrounds, which was consistent with the dominance of Protestantism in Britain at large.[203] Pearson's survey also found that half of British Wiccans featured had a university education and that they tended to work in "healing professions" like medicine or counselling, education, computing, and administration.[204] She noted that there thus was "a certain homogeneity about the background" of British Wiccans.[204]

In the United Kingdom, census figures on religion were first collected in 2001; no detailed statistics were reported outside of the six main religions.[205] For the 2011 census a more detailed breakdown of responses was reported with 56,620 people identifying themselves as pagans, 11,766 as Wiccans and a further 1,276 describing their religion as "Witchcraft".[206]

North America

In the United States, the American Religious Identification Survey has shown significant increases in the number of self-identified Wiccans, from 8,000 in 1990, to 134,000 in 2001, and 342,000 in 2008.[207] Wiccans have also made up significant proportions of various groups within that country; for instance, Wicca is the largest non-Christian faith practised in the United States Air Force, with 1,434 airmen identifying themselves as such.[208] In 2014, the Pew Research Center estimated 0.3% of the US population (~950,000 people) identified as Wiccan or pagan based on a sample size of 35,000.[209]

In 2018, a Pew Research Center study estimated the number of Wiccans in the United States to be at least 1.5 million.[210]

Acceptance

Wicca emerged in predominantly Christian England, and from its inception the religion encountered opposition from certain Christian groups as well as from the popular tabloids like the News of the World. Some Christians still believe that Wicca is a form of Satanism, despite important differences between these two religions.[211] Detractors typically depict Wicca as a form of malevolent Satanism,[17] a characterisation that Wiccans reject.[212] Due to negative connotations associated with witchcraft, many Wiccans continue the traditional practice of secrecy, concealing their faith for fear of persecution. Revealing oneself as a Wiccan to family, friends or colleagues is often termed "coming out of the broom-closet".[213] Attitudes to Christianity vary within the Wiccan movement, stretching from outright rejection to a willingness to work alongside Christians in interfaith endeavours.[214]

The religious studies scholar Graham Harvey wrote that "the popular and prevalent media image [of Wicca] is mostly inaccurate".[215] Pearson similarly noted that "popular and media perceptions of Wicca have often been misleading".[138]

In the United States, a number of legal decisions have improved and validated the status of Wiccans, especially Dettmer v. Landon in 1986. However, Wiccans have encountered opposition from some politicians and Christian organisations,[216][217] including former president of the United States George W. Bush, who stated that he did not believe Wicca to be a religion.[218][219]

In 2007 the United States Department of Veterans Affairs after years of dispute added the Pentacle to the list of emblems of belief that can be included on government-issued markers, headstones, and plaques honoring deceased veterans.[220] In Canada, Heather Botting ("Lady Aurora") and Gary Botting ("Pan"), the original high priestess and high priest of Coven Celeste and founding elders of the Aquarian Tabernacle Church, successfully campaigned the British Columbian government and the federal government in 1995 to allow them to perform recognised Wiccan weddings, to become prison and hospital chaplains, and (in the case of Heather Botting) to become the first officially recognized Wiccan chaplain in a public university.[221][222]

The oath-based system of many Wiccan traditions makes it difficult for "outsider" scholars to study them.[223] For instance, after the anthropologist Tanya Luhrmann revealed information about what she learned as an initiate of a Wiccan coven in her academic study, various Wiccans were upset, believing that she had broken the oaths of secrecy taken at initiation.[224]

References

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ Adler 2005, p. 10.

- ^ Hanegraaff 1996, p. 87; Doyle White 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Crowley 1998, p. 170; Pearson 2002, p. 44; Doyle White 2016, p. 2.

- ^ Strmiska 2005, p. 47; Doyle White 2010, p. 185.

- ^ Strmiska 2005, p. 2; Rountree 2015, p. 4.

- ^ Doyle White 2010, p. 185.

- ^ Strmiska 2005, p. 2.

- ^ Strmiska 2005, p. 21; Doyle White 2016, p. 7.

- ^ Greenwood 1998, pp. 101, 102; Doyle White 2016, p. 8.

- ^ Ezzy 2002, p. 117; Hutton 2002, p. 172.

- ^ Orion 1994, p. 6; Doyle White 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 8.

- ^ Pearson 1998, p. 45; Ezzy 2003, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b c d e Doyle White 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 7.

- ^ Harvey 2007, p. 36.

- ^ a b Doyle White 2016, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Doyle White 2016, p. 4.

- ^ Rountree 2015, p. 19.

- ^ a b Crowley 1998, p. 171.

- ^ a b Doyle White 2010, p. 188.

- ^ a b c Hutton, Ronald (2017). The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present. Yale University Press. p. 121.

- ^ Doyle White 2010, p. 190.

- ^ Doyle White 2010, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Doyle White 2010, p. 193.

- ^ Morris 1969, p. 1548; Doyle White 2010, p. 187; Doyle White 2016, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Doyle White 2010, p. 187.

- ^ Doyle White 2010, p. 195.

- ^ Pearson 2002b, p. 146.

- ^ Doyle White 2010, p. 194.

- ^ Doyle White 2010, pp. 196–197; Doyle White 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Doyle White 2010, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Pearson 2001, p. 52; Doyle White 2016, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, pp. 4, 198.

- ^ Doyle White 2010, pp. 199–201.

- ^ Doyle White 2010, p. 199.

- ^ Pearson 1998, p. 49; Doyle White 2016, p. 86.

- ^ a b Doyle White 2016, p. 86.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, pp. 86–87.

- ^ a b c Doyle White 2016, p. 87.

- ^ Murray 1921.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 91.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 88.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 89.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b c Doyle White 2016, p. 90.

- ^ a b c Pearson, Joanne E. (2005). "Wicca". In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 14. Detroit: Macmaillan Reference USA. p. 9730.

- ^ Farrar & Farrar 1987, pp. 29–37.

- ^ Greenwood 1998, p. 103.

- ^ a b c Doyle White 2016, p. 92.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 93.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 94.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 95.

- ^ Farrar & Bone 2004.

- ^ Adler 1979, pp. 25, 34–35.

- ^ Crowley, Vivianne (1996). Wicca: The Old Religion in the New Millennium. London: Thorsons. p. 129. ISBN 0-7225-3271-7. OCLC 34190941.

- ^ a b c Pearson 1998, p. 52.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, pp. 95–96.

- ^ a b Doyle White 2016, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d e f Doyle White 2016, p. 146.

- ^ Hutton 1999, p. 393.

- ^ a b Doyle White 2016, p. 147.

- ^ Dunwich, Gerina (1998). The A–Z of Wicca. Boxtree. p. 120.

- ^ a b c Valiente 1973, p. 231.

- ^ a b Adler 1979, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Hutton 1999, pp. 394–395.

- ^ Gallagher 2005, pp. 250–265.

- ^ Sanders, Alex (1984). The Alex Sanders Lectures. Magickal Childe. ISBN 0-939708-05-1.

- ^ Gallagher 2005, p. 321.

- ^ a b c d e Hutton 1999.

- ^ Pearson 2002b, p. 164.

- ^ Hanegraaff 2002, p. 303.

- ^ a b Hanegraaff 2002, p. 304.

- ^ a b Pearson 2002b, p. 163.

- ^ Pearson 2002b, p. 167.

- ^ Pearson 2002b, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Mathiesin, Robert; Theitic (2005). The Rede of the Wiccae. Providence: Olympian Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0-9709013-1-3.

- ^ a b Samuel 1998, p. 128.

- ^ a b Hanegraaff 2002, p. 306.

- ^ Harrow, Judy (1985). "Exegesis on the Rede". Harvest. 5 (3). Archived from the original on 14 May 2007.

- ^ Lembke, Karl (2002) The Threefold Law.

- ^ Adams, Luthaneal (2011). The Book of Mirrors. UK: Capall Bann. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-86163-325-5.

- ^ Buckland 1986, Preface to the Second Edition.

- ^ a b Farrar & Farrar 1992.

- ^ Valiente 1989, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b Greenwood 1998, p. 105.

- ^ a b Greenwood 1998, p. 106.

- ^ Gardner 2004, pp. 69, 75.

- ^ Adler 1979, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Pearson 1998, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d Pearson 1998, p. 49.

- ^ Pearson 1998, p. 48.

- ^ Crowley 1998, p. 178.

- ^ Zell-Ravenheart, Oberon; Zell-Ravenheart, Morning Glory (2006). Creating Circles & Ceremonies. Franklin Lakes: New Page Books. p. 42. ISBN 1-56414-864-5.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Gallagher 2005, pp. 77, 78.

- ^ Gallagher 2005.

- ^ Lamond 2004, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Valiente 1989, p. 124.

- ^ Valiente 1973, p. 264.

- ^ Adler 2005, p. 164.

- ^ Adler 2005, p. 172.

- ^ Adler 2005, p. 173.

- ^ Adler 2005, p. 174.

- ^ Greenwood 1998, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Hanegraaff 2002, p. 305.

- ^ McDermott, Matt (2023). Casting Your Own Spell: The Role of Individualism in Wiccan Beliefs. Proceedings of the annual meeting of the Southern Anthropological Society. Vol. 47.

- ^ Pearson 2007, p. 5.

- ^ a b Farrar & Farrar 1981.

- ^ Crowley 1989.

- ^ Bado-Fralick, Nikki (1998). "A Turning on the Wheel of Life: Wiccan Rites of Death". Folklore Forum. 29: 22 – via IUScholarWorks.

- ^ Leland, Charles (1899). Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches. David Nutt. p. 7.

- ^ a b c Pearson 2002b, p. 157.

- ^ Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (1999). The Encyclopedia of Witches and Witchcraft (2nd ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. p. 52. ISBN 0-8160-3849-X.

- ^ Farrar & Farrar 1984, pp. 156–174.

- ^ Urban, Hugh B. (2006-10-04). "The Goddess and the Great Rite Sex Magic and Feminism in the Neo-Pagan Revival". The Goddess and the Great Rite: Sex Magic and Feminism in the Neo-Pagan Revival. pp. 162–190. doi:10.1525/california/9780520247765.003.0008. ISBN 9780520247765.

- ^ Pearson 2005a, p. 36.

- ^ a b Pearson 2005a, p. 32.

- ^ Gary, Gemma (2008). Traditional Witchcraft: A Cornish Book of Ways. Troy Books. p. 147. OCLC 935742668.

- ^ Evans, Emrys (1992). "The Celts". In Cavendish, Richard; Ling, Trevor O. (eds.). Mythology. New York: Little Brown & Company. p. 170. ISBN 0-316-84763-1.

- ^ Gardner 2004, p. 10.

- ^ Lamond 2004, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Crowley 1989, p. 23.

- ^ Gallagher 2005, p. 67.

- ^ Gallagher 2005, p. 72.

- ^ Simpson, Jacqueline (2005). "Witching Culture: Folklore and Neo-Paganism in America". Folklore. 116.

- ^ Farrar & Farrar 1984, Chapter II – Second Degree Initiation.

- ^ Farrar & Farrar 1984, Chapter III – Third Degree Initiation.

- ^ Lewis, James R. (1999). Witchcraft Today: An Encyclopedia of Wiccan and Neopagan Traditions. ABC-CLIO. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-57607-134-2.

- ^ Huson, Paul (1970). Mastering Witchcraft: A Practical Guide for Witches, Warlocks and Covens. New York: Putnum. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-595-42006-0. OCLC 79263.

- ^ Gallagher 2005, p. 370.

- ^ K., Amber (1998). Coven Craft: Witchcraft for Three or More. Llewellyn. p. 280. ISBN 1-56718-018-3.

- ^ Lamond 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Crowley 1989, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Gardner, Gerald (2004a). Naylor, A. R. (ed.). Witchcraft and the Book of Shadows. Thame: I-H-O Books. ISBN 1-872189-52-0.

- ^ Pearson 2002b, p. 135.

- ^ a b c d Pearson 1998, p. 54.

- ^ Doyle White, Ethan (2015). Wicca: History, Belief & Community in Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Liverpool University Press. pp. 160–162.

- ^ "Beaufort House Index of English Traditional Witchcraft". Beaufort House Association. 15 January 1999. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- ^ "Different types of Witchcraft". Hex Archive. Archived from the original on 18 June 2007. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- ^ Pearson 2007, p. 2.

- ^ a b Pearson 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Rountree 2015, p. 16.

- ^ a b Buckland 1986, pp. 17, 18, 53.

- ^ a b c Pearson 2002b, p. 142.

- ^ Pearson 2002b, p. 138.

- ^ Pearson 2002b, p. 139.

- ^ K., Amber (1998). Covencraft: Witchcraft for Three or More. Llewellyn. p. 228. ISBN 1-56718-018-3.

- ^ a b c d Pearson 2002b, p. 136.

- ^ Salomonsen 1998, p. 143.

- ^ Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (1999). The Encyclopedia of Witches and Witchcraft (2nd ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. p. 169. ISBN 0-8160-3849-X.

- ^ Roderick, Timothy (2005). Wicca: A Year and a Day (1st ed.). Saint Paul, Minnesota: Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 0-7387-0621-3. OCLC 57010157.

- ^ Pearson 1998, p. 51.

- ^ Howard, Michael (2010). Modern Wicca. Woodbury, Minnesota: Llewellyn Publications. pp. 299–301. ISBN 978-0-7387-1588-9. OCLC 706883219.

- ^ Smith, Diane (2005). Wicca and Witchcraft for Dummies. Indianapolis, Indiana: Wiley. p. 125. ISBN 0-7645-7834-0. OCLC 61395185.

- ^ Hutton 1991.

- ^ a b Ezzy 2002, p. 117.

- ^ Ezzy 2003, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Ezzy 2003, p. 50.

- ^ a b Doyle White 2016, p. 2.

- ^ a b Doyle White 2016, p. 14.

- ^ Hutton 2003, pp. 279–230; Doyle White 2016, p. 14.

- ^ Baker 1996, p. 187; Magliocco 1996, p. 94; Doyle White 2016, p. 14.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 13.

- ^ Pearson 2002, p. 32.

- ^ a b Guiley, Rosemary Ellen (1999). The Encyclopedia of Witches and Witchcraft (2nd ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. p. 234. ISBN 0-8160-3849-X.

- ^ Buckland 2002, p. 96.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 15.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Jacqueline Simpson (1994). Margaret Murray: Who Believed Her, and Why? Folklore, 105:1-2: 89-96. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1994.9715877

- ^ Doyle White 2016, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Buckland 2002, 10: Roots of Modern Wica.

- ^ Allen, Charlotte (January 2001). "The Scholars and the Goddess". The Atlantic Monthly (287). OCLC 202832236.

- ^ Davis, Philip G (1998). Goddess Unmasked. Dallas: Spence. ISBN 0-9653208-9-8.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Doyle White 2016, pp. 20–22.

- ^ Heselton, Philip (November 2001). Wiccan Roots: Gerald Gardner and the Modern Witchcraft Revival. Freshfields, Chieveley, Berkshire: Capall Bann Pub. ISBN 1-86163-110-3. OCLC 46955899.

Drury, Nevill (2003). "Why Does Aleister Crowley Still Matter?". In Metzger, Richard (ed.). Book of Lies: The Disinformation Guide to Magick and the Occult. New York: Disinformation Books. ISBN 0-9713942-7-X. OCLC 815051948. - ^ Bourne, Lois (1998). Dancing With Witches. London: Robert Hale. p. 51. ISBN 0-7090-6223-0. OCLC 39117828.

- ^ Heselton, Philip (2003). Gerald Gardner and the Cauldron of Inspiration. Somerset: Capall Bann. p. 254. ISBN 1-86163-164-2. OCLC 182799618.

- ^ Hutton 1999, p. 289.

- ^ Valiente 1989, p. 60.

- ^ Lamond 2004, pp. 30–31.