Contents

Emanoil Băleanu (Transitional Cyrillic: Eманoiл БълeaнȢ or БълѣнȢ; French: Emmanuel Balliano[1] or Manuel de Balliano;[2] Greek: Ὲμανοὴλ Παλλιάνοσ, Emanoil Pallianos;[3] also known as Manole, Manoil, Manuil or Manolache Băleanu; 1793 or 1794–1862), was a Wallachian statesman, soldier and industrialist who served as Caimacam (regent) in October 1858–January 1859. Descending from an old family of boyars, he was one of two sons born to Ban Grigore III Băleanu; the other, Nicolae, was a career bureaucrat, and the State Secretary of Wallachia in 1855–1856. Although prone to displays of Romanian nationalism, the family was prominent under the cosmopolitan Phanariotes, and young Băleanu was educated in Greek. Prince Alexandros Soutzos welcomed him at the court and became his father-in-law. At that stage, Băleanu's participation in the spoils system was signaled by his highly controversial claim to ownership of Târgoviște city, and also by his monopoly on handkerchief manufacture. A slaveowner, he founded the village of Bolintin-Deal, initially populated by his captive Romanies.

His father hoped to steer the anti-Phanariote revolt of 1821, but both he and Emanoil were driven into exile when Bucharest fell to the rebels. In exile, Băleanu Jr began gravitating toward liberalism, before becoming curious about utopian socialism. Under the Regulamentul Organic regime, he was made Polkovnik in the Wallachian military forces and served two terms in the Ordinary National Assembly. He and Ioan Câmpineanu emerged as leaders of the "National Party", which mounted the opposition to Alexandru II Ghica and uncovered constitutional irregularities. Băleanu was sent into internal exile in 1841, but reinstated following interventions by his friends in the Russian Empire and the Wallachian Church. He ran in the princely election of 1842, but conceded defeat in favor of his friend Gheorghe Bibescu, who then made him his Postelnic (1843–1847). As such, Băleanu contributed directly to the modernization of Wallachia, and also to the early stages of abolitionism—though he himself remained a slaveowner to 1855.

Băleanu joined the conservative camp during the Wallachian Revolution of 1848. For a few days in June–July of that year, he proclaimed himself Caimacam, heading a reactionary administration alongside Metropolitan Neofit II. Before being deposed and driven out of Wallachia, he gave the order to destroy revolutionary symbols, including the "Statue of Liberty". Returning with the Ottoman Army, he was again promoted under Prince Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei, and especially during the late stages of the Crimean War, which removed Russian tutelage. His focus fell on obtaining a close alliance between Wallachia and the Austrian Empire.

Băleanu's second, internationally recognized, term as Caimacam was within a triumvirate that also included Ioan Filipescu-Vulpache and Ioan Manu; alongside the latter, Băleanu instituted a repressive regime, directing censorship and intimidation against the National Party. They organized the legislative elections of 1859, but were outmaneuvered by liberals and nationalists, who managed to push through their agenda. Băleanu was brutalized and shunned during events leading up to the establishment of the United Principalities, which put an end to his political career. His only literary work was a manuscript chronicle, which was later exposed as plagiarized.

Biography

Early life

The Băleanus, whose history is linked to an eponymous estate in Dâmbovița County, belonged to Wallachia's older lineage of boyar nobility, and claimed kinship with the ancient House of Basarab.[4] The family patriarch was Udrea Băleanu, who served as Ban of Oltenia in the 1590s.[5] His nephew, Ivașco I Băleanu, emerged as a powerful player in 1630s Wallachia, having backed Matei Basarab for Wallachia's throne; his son, Gheorghe Băleanu, similarly endorsed and fought alongside Constantin Șerban.[6] He was prominent into the 1670s, when he and his family feuded with the Cantacuzinos; their conflict came to an end in 1679, when Gheorghe's son, Ivașco II, was sent into exile.[7] By the late 18th century, the family (one of the 16 boyar clans which could claim an ancient Wallachian origin) had secured major feudal privileges, including tax farming on their estates—one of only four families to maintain that favor.[8]

Emanoil was Ivașco II's great-great-grandson.[9] He was born in 1793 or 1794 as the son of Ban Grigore III Băleanu (1770–1842) and his wife Maria, née Brâncoveanu (?–1837).[10] On his mother's side, he was a collateral descendant of Wallachian Prince Constantin Brâncoveanu; Maria's brother, also named Grigore, was the last male of the Craiovești-Brâncoveanu family.[11] His maternal grandmother was a member of a Moldavian clan, the Sturdzas.[12] Emanoil's siblings included a sister, Zoe (1791–1877). In 1811–1815, she was married to the aristocrat Matei Ghika, but divorced when he fell ill with tuberculosis.[13] One contemporary account suggests that she then became the wife of Dimitri Caragea, a relative of Prince John Caradja.[14] Zoe's last husband was entrepreneur Ștefan Hagi-Moscu.[15] Zoe and Emanoil had a brother, Nicolae, as well as two other sisters: Elena, married to Constantin Năsturel-Herescu; and Luxița, whose husband was writer Nicolae Văcărescu.[16]

Emanoil's childhood and youth coincided with the closing stages of the Phanariote era, during which Wallachia and Moldavia (the "Danubian Principalities") were more closely integrated with the Ottoman Empire, and Greek immigration became more significant. Father Grigore was involved with the Phanariote administration of Bucharest and owned houses just west of Turnul Colței.[17] He was first propelled to the high office of Spatharios and Logothete during the Russo-Turkish War of 1806–1812, when he supported occupation by the Russian Empire,[18] receiving the Order of Saint Anna.[19] A patron of literature, he regularly donated from his collection of books, paid for a translation of Condillac's essays, and reportedly began writing a Romanian dictionary.[20] In 1816, he sponsored Pete Efesiul's print shop—Wallachia's first publisher of sheet music.[21]

Emanoil was home-schooled in the city by the Greek tutor Kirkireu, who introduced him to the Phanariote court.[22] A contemporary note by journalist and editor Zaharia Carcalechi suggests that Emanoil and Nicolae Băleanu were both educated in the Kingdom of France and the Austrian Empire—though, as historian Nestor Camariano concluded in 1946, it is impossible to know when and for how long Emanoil was actually abroad.[23] Although one late record suggests that he was also raised in Germany,[24] Greek remained his favorite language of expression even later in life.[25] At some point in his youth (probably before 1818), Emanoil produced a chronicle of documenting the history of Roman Dacia and the Early Middle Ages. The manuscript was much later exposed as plagiarized version of a similar work by Theodoros Photeinos (Teodor Fotino), which in turn may have copied a since-lost book by Dionisie Fotino.[26] As noted by Camariano, "nothing [else] remains, whether published or in manuscript" from Băleanu the writer.[27]

Slaveowner and political novice

Historian Radu Crutzescu proposes that Emanoil's political rise was in large part owed to his kinship with two families: the Văcărescus and the Soutzos; he was uncle of Marițica Văcărescu, who was to become Prince Gheorghe Bibescu's wife, and, through his marriage with Catinca, son-in-law of Wallachia's last Phanariote Prince, Alexandros Soutzos.[28] A Wallachian comedy of ca. 1820 shows Ban Grigore trafficking in influence to benefit his in-laws.[29] Phanariote favoritism was also noted by memoirist Ion Ghica. He mentions that Emanoil's Greek education is what drew Prince Soutzos' attention. Upon his wedding to Catinca, Băleanu received ownership of Târgoviște, which the Prince had abusively claimed as his own; when news of this deal reached the sparked city, the rioting citizens placed a jinx on Soutzos' house.[30] Catinca's dowry also included a monopoly on the manufacture of handkerchiefs, which came with additional tax privileges and the right to employ 30 foreign laborers. This included ownership of the textile mill at Mărcuța Church, which Băleanu immediately leased to a Russian immigrant.[31]

Emanoil Băleanu first reached high office in 1819, when he served as Wallachia's junior Minister of Internal Affairs, or Vornic; he was the country's highest Logothete in 1821.[32] Around 1800, he had begun constructing a manor for himself, at a new spot clear-cut from Vlăsiei Forest, between Târgoviște and Bucharest. He and his family were traditional slaveowners, bringing with them a large number of captive Romanies; these were settled into a village that was originally named "Băleanu".[33] Around 1816, the completion of a road drew in Romanians from the neighboring Bolintin-Spiridon, which became depopulated. The resulting rural agglomeration became Bolintin-Deal, which is still informally divided into Berceni and Băleanu villages; both of them were populated by his tenant farmers, slaves and non-slaves alike.[33]

Catinca died in childbirth one year into their marriage, in what was seen by contemporaries as proof that Băleanu was under the "Târgoviște jinx".[34] Despite his son's matrimonial arrangement with the Phanariotes, Grigore Băleanu was one of the more independently minded boyars, who was made unassailable by his acceptance into a Janissary corps and his employment of a personal guard.[35] Proud of his Romanian roots, and "in touch with tradition", he reportedly organized street parades that "made Greeks quiver."[36] Soutzos' death in January 1821 sparked a political crisis, making Wallachia into a theater for the Greek War of Independence. In parallel, there was an anti-Phanariote uprising in Oltenia, which Grigore may have personally have encouraged: he is alleged to have staged Soutzos' poisoning alongside members of the Filiki Eteria, after which he returned as Spatharios.[37]

Băleanu Sr is additionally cited as one of the boyars who reached out to the rebel leader, Tudor Vladimirescu, and invited him to act on their behalf.[38] His son-in-law Năsturel-Herescu joined the Eteria, and was consequently a soldier in the Sacred Band.[39] The revolt was soon uncontrollable, and intrinsically anti-boyar in scope. The mill of Mărcuța was looted and rendered inoperable.[40] Escaping the threat of a full-blown civil war, the Băleanus took refuge in the Austrian-held Principality of Transylvania, joining a colony of boyar expatriates in Corona (Brașov).[41] It was here that Emanoil was inducted into a secretive group of exiles, the "Brașov Society", whose founding members included his father.[42] He was subsequently initiated by the Freemasonry.[43]

On May 24, following a showdown between Vladimirescu's men and the Eteria, members of the latter called on Grigore to return and seize control of Wallachia.[44] Later in 1821, the Ottoman Army invaded and restored the old regime; Nicolae Băleanu, who had "some part to play in the insurrection", fled with the Eterists and made his way to Hermannstadt.[45] Both Băleanus signed their names to the letter demanding that the new Prince Grigore IV Ghica send them funds to ensure their safe return to Bucharest in 1822.[27] Upon their return, Grigore Băleanu Ghica as the country's Vornic.[46] Nicolae and his Greek tutor Mavromati spent this interval in France, where the former was supposed to further his studies. Both were seen as dangerous suspects by agents of the Sûreté.[45]

The post-Eteria arrangement was ended by the war of 1828, which again saw both Principalities invaded by the Russian Empire. In 1829–1830, at the height of occupation, Emanoil Băleanu joined the Special Committee for Reform, created by the Russians in order to confirm the constitutional principles that were to govern Wallachia and Moldavia. The committee, presided upon by Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei, also included Iordache Filipescu, Alexandru Vilara, and Ștefan Bălăceanu; it mounted resistance to Russian proposals for tax reforms, especially in opposing the notion that boyars could pay a direct tax.[47] The Russians and Ottomans finally reached a compromise on joint rule over the principalities, and granted them a charter, Regulamentul Organic, which codified their fundamental laws. This document, produced in 1831, was partly co-written by Grigore Băleanu and Iordache Filipescu.[48]

Regulamentul introduction

The throne in Bucharest was assigned to Alexandru II Ghica, who presided over an era of Westernization. Historian Bogdan Bucur notes that, under the Regulamentul regime and its "bourgeois era", the Băleanus were the third most powerful clan of Wallachian boyars, ranking below the Filipescus and the Ghicas.[49] In 1830, formally renouncing Ottoman clothing,[50] Emanoil Băleanu was integrated within the restored and modernized Wallachian military forces. He was one of the last boyars to be granted automatic advancement based on high birth, and almost immediately received the rank of Polkovnik (Colonel).[51] He was first assigned command over the 1st Infantry Regiment at Craiova, serving under Russian commanders. His own subordinates included two future conservative polemicists, Grigore Lăcusteanu[52] and Dimitrie Papazoglu.[53] Băleanu was stationed in Bucharest in 1831, when Wallachia was hit by the second cholera pandemic. As reported by Lăcusteanu, Russian overseer Pavel Kiselyov held Băleanu and Ioan Odobescu responsible for the poor hygiene at Filantropia Hospital. Both were "arrested inside the hospital" and only released following its complete sanitation. According to Lăcusteanu, they relied on take-out food and slept at a local pub.[54]

While his father was a sponsor of the conservative poet Grigore Alexandrescu,[55] Băleanu Jr was sympathetic to Wallachian liberalism, and welcomed in his home Teodor Diamant, who actively campaigned in favor of Fourierism.[56] He consolidated his standing in 1831, taking over as Wallachia's Great Hatman; simultaneously, in the election of 1831 he acquired a seat in the Ordinary National Assembly.[28] The Prince nominated him and Constantin Bălăceanu to settle a long-running conflict between regular Wallachian Jews and their government-sanctioned leader, or Staroste. They failed to reach an understanding, simply reconfirming the Staroste to his position, where he remained for the next decade.[57] Meanwhile, Băleanu, Ioan Câmpineanu, Grigore Cantacuzino and Iancu Ruset presided over a liberal faction sometimes labeled as "National Party", and by 1834 produced designs on how to rewrite Regulamentul into a set of reformist policies.[58] By then, Băleanu had also helped set up a Philharmonic Society, which promoted culture along with liberal ideas.[59]

As a member of the Assembly, Băleanu also reported on the status of Romani slaves. Mainly as a tactic for enlarging the state's fiscal revenues over a longer period, he proposed that government purchase and manumit slaves owned by the boyars. In order to provide funds for this initial effort, he instituted a custom whereby the Romanies, whether slaves or not, were to be assimilated with tenant farmers, and subjected to a poll tax; between 1833 and 1839, 185 slaves were emancipated using this system.[60] The Băleanus were otherwise still committed to the preservation of traditional institutions, including slavery. The family owned eight villages (four of which were in Dâmbovița), which in 1833 fetched them a total of 53,300 thaler in rents.[61] In January 1837, Grigore sold off a family of Romanies to a Stavrache Iacov.[62]

In 1832,[63] Băleanu married Alina Bagration, daughter of a Russian officer and Bagratid descendant. She had a public affair with Kiselyov, and went with him to Russia in 1834. Băleanu consented to a divorce in 1836, after which Alina moved in with Kiselyov and his wife Zofia Potocka.[64] He held on to his Assembly seat following the 1836 election, which saw his father taking over as chief minister.[48] According to Ion Ghica, the Nationals' "four-man party" controlled a majority of the Assembly seats, earning backing from Ilarion Gheorghiadis and other hierarchs of the Wallachian Church.[65] As members of the Assembly, both Emanoil and Grigore supported the state religion and opposed attempts by the regime to infringe upon its liberties and privileges.[66] From June of that year, Băleanu Jr, Câmpineanu, Ruset and Alecu "Căciulă-Mare" Ghica joined the Regulamentul revision committee.[67] While researching the matter, they discovered that Russian officials had forged Regulamentul, tying to the original text an "additional article", which indicated that the legislation could not be modified by the Wallachians alone. Although the article remained in place and was recognized as valid by the Ottomans, the scandal was helped to consolidate Romanian nationalism and anti-Russian sentiment throughout Wallachia.[68]

Travel notes left by the Frenchman Stanislas Bellanger suggest that the former Hatman attended subversive meetings with Xavier Vilacrosse and other expatriates, where they discussed founding a Wallachian magazine; Bellanger notes that Băleanu wanted the publication to be non-political.[69] By 1838, Băleanu, Câmpineanu, Ruset and Costache Faca were members of the Assembly's financial board, questioning government's spending practices and attempting to draw more funds into education.[70] In 1839, Prince Ghica appointed Băleanu as his Minister of Justice, or Great Logothete, although he subsequently reassigned him to Internal Affairs, as Vornic.[28] In July of that year, a commission comprising Băleanu, Ioan Slătineanu and Petrache Poenaru was sent by Ghica to inspect the Austrian–Wallachian border on the Cerna, after numerous reports that Austria was violating the Treaty of Sistova. The Austrians snubbed them as negotiators, informing them that they would only settle border issue with imperial Ottoman envoys.[71]

1842 election

Băleanu soon joined the anti-Ghica faction, which by then included brothers Bibescu and Știrbei among its leaders.[72] Speaking at the closure of the Assembly in December, the monarch made disgruntled allusions to Băleanu and Câmpineanu, claiming that both had lied in petitions they sent to foreign governments.[73] However, in 1840, he appointed Băleanu as one of the efori (caretakers) of Wallachia's schools, alongside Apostol Arsache, Ion Heliade Rădulescu, and "Căciulă-Mare";[74] he was also assigned to the appellate commercial court.[27] On January 29, 1841, after noting his "disrespectful statements" in the Assembly, Prince Ghica ordered Băleanu into internal exile. Sources give his place of banishment as Varnița[75] or Bolintin.[76] According to notes left by Jean Alexandre Vaillant, his ouster was part of a general clampdown on subversive activities, along with the imprisonment of conspirators Mitică Filipescu and Andrey Deshov, and with Vaillant's own expulsion from Wallachia.[77] By then, Băleanu's Fourierist friends were also targets of repression: Diamant's Scăieni Phalanstery had been forcefully closed, and his attempts to contact Băleanu were thwarted.[78]

This clampdown proved to be a miscalculation of Băleanu's support by Russian diplomats and Church officials alike: Metropolitan Neofit II and consul Iakov Dashkov pressured him to withdraw the order, which Prince Ghica did on February 3.[79] Băleanu remained the central figure of the opposition.[80] In March 1841 he oversaw a ceremony for Kiselyov's retirement. Kiselyov was granted Wallachian citizenship on the occasion, prompting speculation that Băleanu was grooming him for the princely throne.[81] As reported at the time by Vaillant, Băleanu conceived of the naturalization as a personal revenge against Ghica.[82] Returning as Logothete, he joined "Căciulă-Mare", Slătineanu, Vilara and Ioan Filipescu-Vulpache on the Commission which validated the Assembly elections of January 1841.[83] In June, he proposed that a monument to Kiselyov be completed using funds from the national reserve, which implied tapping into the farmers' tax revenue. As noted by the Erdélyi Híradó correspondent, "Prince Ghika was very incensed at this, and could hardly be restrained from taking further steps against Baliano."[84]

During its final months, the Ghica regime still relied on support from the elder Băleanu, who served as Vornic in June 1842.[85] Following Ghica's ouster, Băleanu Jr presented himself for the princely election, also serving as an elector; his father was also listed as "fit to be Prince", but died of coronary artery disease before the electors convened.[86] Băleanu Jr took most votes (79) in the third section.[87] However, he redirected these toward his "intimate friend" Bibescu,[88] who emerged as the winner. On June 29, 1843,[89] Băleanu entered the princely cabinet as State Secretary, or Postelnic. His office unified the attributes of a civil registrar, censor, and Foreign Minister.[90] In this capacity, Băleanu countersigned orders to expand and modernize the port of Brăila (August 1843) and protect insolvent farmers (June 1845), as well as publishing a firman confirming free trade between Wallachia and the Ottoman Empire (October 1843).[91] His brother had by then established himself as one of Wallachia's leading textile manufacturers, using Austrian know-how to set up a modern factory in Tunari.[92]

During the election, Băleanu had been favored by the French consul Adolphe Billecocq, who deeply disliked the "Gypsy" Bibescu.[93] In 1844 the Postelnic dealt with the issue of French counterfeiters in Wallachia, which, despite Billecocq's protests, were slated for extradition and execution in the Ottoman Empire.[94] From January 1845, Băleanu was involved in the beautification of Bucharest, and sketched a project for building new roads between all Wallachian towns.[95] In parallel, as members of the Extraordinary Administrative Council, Băleanu, Câmpineanu, Filipescu-Vulpache, Vilara and Costache Ghica ruled in favor of dissolving the underdeveloped Saac Country, whose territory was split between the more prosperous Prahova and Buzău.[96] Also in 1844, the Assembly appointed him, together with Vilara and Alecu Filipescu-Vulpea, to oversee the charity known as Așezămintele Brâncovenești. This had been set up for Bibescu's estranged wife Zoe Brâncoveanu, whom the prince had declared insane,[97] and who was Băleanu's cousin.[12]

On April 19, 1845, Băleanu married his third and last wife—Elena (or Sultana), daughter of his colleague Constantin Bălăceanu.[98] In May of the following year, Bibescu took him to Ruschuk, where they paid homage to their sovereign, Sultan Abdulmejid I.[99] Also that month, the Postelnic was accused by Billecocq of having failed to pay homages to Louis Philippe I on the feast day of Saint Philip. A review of this incident, published by Adevĕrul in 1893, suggests that Băleanu was framed by Billecocq, who needed a diplomatic incident to conceal his own recall and disgrace.[100] For a few days in September 1846, while Bibescu and Vilara inspected Oltenia, Băleanu was effectively the leader of the country, and ad interim Minister of Justice.[101] On February 11, 1847, Bibescu and Băleanu urged the Assembly to debate on the issue of slavery. The result of this deliberation was a partial abolition, namely the release of all Romanies held captive by the Wallachian Church.[102]

1848 Revolution

Băleanu helped Bibescu to dissolve the Assembly on March 11, 1847.[103] Fifteen days later, he was involved in disaster relief following a devastating fire in Bucharest, overseeing the reallocation of funds.[104] His own family home had been destroyed by flames.[105] On March 31, he signed his name to the customs union between Wallachia and Moldavia.[106] However, in the government reshuffle of May he lost the position of Secretary, which went to Constantin Filipescu; on May 11, he became an honorary Vornic, alongside Vilara.[107] From August, he was again efor on the national school board.[108] Băleanu returned as Minister of Justice in December 1847, when he ordered a clampdown on frivolous litigators and the clarification of mulcts.[109] By January 1848, he and Filipescu-Vulpache sat on a committee tasked with constructing a National Theater, but the entire project (supported by the Philharmonic Society)[27] was shelved before taking off.[110]

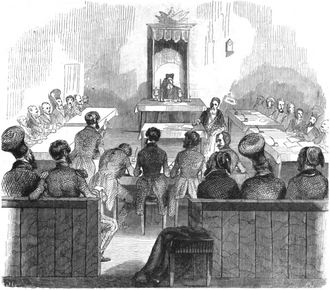

Initially, Băleanu and Bibescu were open toward the nationalist and liberal groups: by 1845, both had subscribed to Nicolae Bălcescu's literary review, Magasin Istoric pentru Dacia.[111] Within three years, the two camps had come to oppose each other openly. Early June 1848 witnessed the eruption of a Wallachia's liberal Revolution, which first limited Bibescu's authoritarian rule, then deposed him. As reported in Nemzeti newspaper, the "large crowds" gathered, which threatened to have the princely guards "stoned to death" and carried a "blue-and-white flag", also chanted messages specifically against Băleanu. As Bibescu agreed to abdicate, his courtiers also lost executive positions—Băleanu's position as Minister of Justice went to the rebel-rouser Ștefan Golescu.[112] The boyars assembled separately and elected Băleanu as Caimacam, or co-regent, alongside Neofit and Ban Teodor Văcărescu-Furtună; they were deposed after attempting to reverse the revolutionary trend.[113]

Later that month, generalized panic was created by rumors of a Russian incursion in Wallachia, and the revolutionary administration abandoned Bucharest for the more secluded town of Rucăr. On June 29, Neofit seized the opportunity and established another conservative government. Băleanu became Caimacam, alongside Filipescu-Vulpache and Văcărescu-Furtună.[114] According to Lăcusteanu, in public perception Băleanu held the "reins of government"; his army colleague Odobescu was the Minister of War.[115] During his short interval in power, he dismantled and destroyed revolutionary symbols. These famously included a Statue of Liberty, possibly by Constantin Daniel Rosenthal,[116] but also a composition depicting "free Romania".[117] Băleanu also reinstated Bibescu's police force, including a Captain Costache Chioru, who reportedly shouted his intention to exercise a brutal revenge on the revolutionaries: "I shall make myself a whip from the skins of Romanians".[118]

This return to conservatism immediately upset the lower strata: on the night of the coup, a Petre Cârciumaru of Olari mahala reportedly threatened to kill Commissioner Ion Bidu; the following morning, a group of men from Delea Veche Street, flying a flag of their own making, stormed the neighboring area and threw stones into Băleanu's townhouse.[119] On July 3, the Bucharest bourgeoisie stormed into the army barracks, forcing the government to resign.[120] The 40,000-strong crowd, led into battle by Ion Brătianu and Hieromonk Ambrozie "Popa Tun", won Odobescu's troops over to its side, without bloodshed.[121] Neofit, captured by the crowds, declared that the previous coup had been instigated by Băleanu and Iordache Zossima. This prompted the revolutionaries to vandalize Băleanu's home and lynch as many of his partisans as they could find[122] (part of a larger raid, which also resulted in the devastation of Zossima and Chioru's houses).[123] The revolutionary gazette Pruncul Român depicted Băleanu himself as a vandal, calling attention to his earlier artistic purge.[116] The incident was also noted by the far-left radical Bălcescu, who insisted that government make its resolutions into permanent laws. According to Bălcescu, Băleanu was to be prevented from ever returning to Bucharest.[124]

By then the deposed Caimacam had again fled to Corona, joining a conservative faction in exile. It also included Slătineanu, Scarlat Ghica, and Nicolae Suțu.[125] In September 1848, the Ottomans invaded and occupied Wallachia, which was again placed under a conservative regime. With Constantin Cantacuzino as Wallachia's new Caimacam, Băleanu, Filipescu-Vulpea and Poenaru returned as efori, and staged a clampdown on revolutionary teachers.[126] His brother Nicolae was appointed a Logothete, and served in the post-revolutionary administration of Bucharest. In October, he networked between the city guilds to ensure that the city and the Ottoman Army were properly supplied with bread.[127]

Știrbei was afterwards crowned Prince, more fully restoring the Regulamentul regime. On August 24, 1850, he made Emanoil his Minister of the Interior, within a cabinet of "relatives and intimate friends".[128] He also returned as chairman of the Assembly,[113] and, by 1851, was serving on a committee which liquidated Wallachia's debt toward Austria.[129] Nevertheless, for several years after the Revolution's defeat, Băleanu failed to impose himself in political life: the newspaper Vestitorul Românesc dismissed him as "entirely unremarkable".[28] He had by then returned to his activities as an industrialist, with a new textile factory, which employed as many as 200 workers, opened in Dragomirești.[130] He stood out among conservatives for opposing all attempt at implementing land reform, and also for resisting the projected reductions of boyar privilege.[131] Băleanu also remained a slave-owner and, in May 1850, had a runaway Romani family returned to him by the authorities in Dolj County.[132]

Triumvirate

The Regulamentul period ended during the Crimean War, which was a clash between the Principalities' Russian and Ottoman protectors. Știrbei left Wallachia, without abdicating, in October 1853 and his cabinet continued to function.[133] In April 1854, Spatharios Năsturel-Herescu sought to integrate the Wallachian army into Halim Pasha's Ottoman troops; on August 23, Omar Pasha instituted martial law, and on August 31 set up a new government, headed by Năsturel and Cantacuzino.[134] By then, Austria had effectively occupied Wallachia, and the Ottoman presence was symbolic. In that context, Nicolae Băleanu was involved in state-sponsored abolitionism, serving on a financial committee that also included Ioan Manu, and later as Chairman of the Wallachian Treasury.[135]

Știrbei returned as an Austrian protégé on September 23, creating himself a new cabinet, with Nicolae Băleanu serving as State Secretary.[136] After originally resigning in protest against Știrbei's appointment,[137] Emanoil returned as Interior Minister. As reported by Constituționalul newspaper, he was included on the cabinet in order to placate him, "for many years one of the most influential members of the opposition".[138] On December 14, 1855, both brothers, alongside Câmpineanu, Filipescu-Vulpache, Alexandru Plagino and George Barbu Știrbei, signed the decree which emancipated all of Wallachia's 200,000 slaves.[139] Emanoil then oversaw the effort to count and register the newly freed Romanies.[140] In early 1856, he rallied with anti-Știrbeist boyars and signed a formal letter of protest. In order to win him over, on February 26 (New Style: March 9) the Prince appointed him Ban of Oltenia. As reported by the poet Alexandrescu, the ceremony ended in "Homeric laughter" when Băleanu, overtaken with joy, sat down on the wrong side of the princely carriage.[141]

Meanwhile, Austrian occupation was giving way to a shared custody of Wallachia and Moldavia by a consortium of European powers, backing Ottoman suzerainty. Prince Știrbei finally resigned on June 25, 1856: from Pitești, he declared Secretary Nicolae Băleanu as the highest authority in Wallachia. On July 4, he resigned in favor of his brother's enemy, Alexandru II Ghica, who took the title of Caimacam.[142] Ghica turned increasingly liberal, and was regarded by his Austrian supervisors as "almost child-like";[143] the Băleanus, meanwhile, endured as conservative leaders. That year, poet Dimitrie Bolintineanu characterized Emanoil as a figure out of Molière's comedies and an ultra-reactionary: "he wishes to preserve all titles, honors, privileges, [and] has protection from Russia and Austria".[63] Overall, Bolintineanu contended, Băleanu was a "revolting nonentity".[144] While similarly noting Băleanu's Austrian sympathies, Franz von Wimpffen cautioned that he was also lazy, unintelligent, and corrupt.[24] With this platform and backing, Băleanu ran in the September 1857 election and took a seat in the Assembly, which had been reconstructed and enlarged as an "ad hoc Divan".[117]

On October 21, 1858,[145] Emanoil Băleanu, Manu and Filipescu-Vulpache were formally appointed as Caimacami. The firman confirming this arrangement specified that Băleanu oversaw Internal Affairs, while Vulpache was Logothete and Manu chaired the Divan.[63] Băleanu's return was especially controversial: he was now regarded as a leading adversary of the National Party, which sought to obtain a union between Wallachia and Moldavia.[146] As noted in its paper, Stéoa Dunărei, the three rulers were allowed unconstitutional, and unexplained, freedom of action. The Sublime Porte remained unresponsive as "they changed all of the country's employed officials, from Ministers and down to the lower magistrates" (aȣ ckimБaтȣ тoтȣ пeȣрconaлȣл amплoĭaцiлoр цepeĭ, de лa Minicтpiĭ пъnъ лa cȣБokъpmȣiтopĭ).[147] Băleanu and Manu clashed with the more liberal Vulpache as early as October 29, when they promoted their political friend Slătineanu as Minister of Education.[148] The two conservative Caimacami were in a position to control the new elections for the Divan, and were widely suspected of intending to manipulate results. Threats were posted on their townhouse gates, describing them as the "bandit brothers"[149] and hinting at popular revenge. An incendiary device was reportedly thrown into Manu's home.[1]

In December, after the breakdown of negotiations between foreign diplomats, the issue of electoral fraud became an international scandal.[150] Revelations had also emerged that the Caimacami had denied eligibility to some of the leading National-Party candidates, including Vasile Boerescu, Cezar Bolliac, and C. A. Rosetti. Such restrictions relied on different readings of the suffrage qualifications: while Manu and Băleanu argued that candidates needed to own landed estates, Vulpache offered a dissenting opinion, with no restrictions for burghers or industrialists; this created a definitive schism within the regency, and pushed Vulpache closer to the National Party.[151] Though they went back on some of their more controversial decisions, the other two Caimacami proceeded to govern by increasingly dictatorial means, suspending judicial independence, generalizing censorship, and ordering troops to mobilize in areas of the country that showed vocal support for unionism.[152] The regency also restricted all forms of electoral propaganda.[153]

Downfall and death

The elections doubled as a contest for the princely throne, with both Bibescu and Știrbei entering the race. Although Băleanu himself was a client of both former princes, he registered as a candidate, with his new title of Ban, also running against his father-in-law Bălăceanu.[154] On this second attempt, he was credited with minimal chances, being an "unexpected" contender.[155] As the Divan began its proceedings, he was confronted with events such as the peasants' march on Bucharest, in support of the National Party. According to reports picked up by the Pester Lloyd, his troops fired on the crowds. Several protesters were wounded or killed in this standoff; Băleanu called the soldiers off, after being reassured that the march was non-violent. He drafted an appeal to the Bucharesters, "which was given the widest possible distribution by means of comments in inns [and] postings at street-corners", asking them "not to contribute to the excitement, and not to degrade the celebration of this day". However, "as the Caimacami Mano and Baleano left the meeting hall and approached their carriages, a voice, echoed by many other voices, followed them: 'Down with Mano, down with Baleano.' One would have to reach back deep into history to find another man as detested as these two presently are."[156]

The elections produced unintended results for all of the conservative groups: backed by radicalized crowds numbering in the thousands, the National Party was able to pass resolutions in favor of union. A rallying speech by Boerescu united unionist conservatives and radicals around Alexandru Ioan Cuza, who had already carried the Moldavian election, and against conservative separatists such as Băleanu. During this process, the other deputies stripped Băleanu, Manu, Ioan Hagiadi and Mihalache Pleșoianu of their voting rights—along with Alexandru Ghica and Radu C. Golescu, who opted to step down voluntarily.[157] As reported by Alexandru G. Golescu, "that swine Manu" and "that idiot Băleanu" had to leave the Divan's hall and were heckled and threatened as they returned to their homes.[158] He also suggests that Băleanu begged the crowd for forgiveness, but was merely derided.[159]

On January 23, a crowd comprising "thousands of people", grouped under N. T. Orășanu, marched on the Caimacam's home: "it appears that E. Băleanu fainted for fear that a revolution had started".[160] A day later, the Divan elected Cuza, who was thus positioned to create the United Principalities—initially as a personal union, with himself as Domnitor. Băleanu left Wallachia during the union process, and in June 1859 had reached the Grand Duchy of Baden.[2] His final will, completed in March 1861, suggest that he no longer held, or considered relevant, any of his father's houses in Băleni; by 1873, these were in a state of advanced ruin.[161] Băleanu died in 1862, and was buried at Bolintin-Deal,[48] whose main church he had dedicated himself in 1856.[33] His widow Elena survived him until 1865.[113] Ion Ghica was appointed their executor, in which capacity he demanded a survey on the estates of Corbii and Vânătorii; in 1866–1867, his land dispute with the local peasants led the latter to riot.[162] This was contrasted by the situation in Bolintin-Deal, where, before and during the 1864 land reform, the Romanians and Romanies alike had purchased 80% of the land they had been assigned for work.[33] Băleanu was also survived by his brother Nicolae (to 1868),[163] by his sons Emanuel, who served in the Senate of Romania, and George; and by daughters Maria and Elena.[164] His niece Zoe Hagi-Moscu (1819–1904) was the wife of politician Constantin N. Brăiloiu.[12]

Notes

- ^ a b "Télégraphie privée", in Journal des Débats, December 19, 1858, p. 1

- ^ a b "Histoire de la semaine", in L'Illustration de Bade, Vol. 2, Issue 6, June 1859, p. 41

- ^ Camariano, p. 145

- ^ Chirică, p. 352; Lecca, p. 9

- ^ Potra (1990 II), p. 154

- ^ Stoicescu, pp. 114–116

- ^ Stoicescu, pp. 116–118, 135–139, 165, 173, 195–196, 215–216

- ^ Bucur, pp. 32–33, 35

- ^ Lecca, p. 9; Păduraru, pp. 98–103

- ^ Crutzescu & Teodorescu, p. 498; Ion & Berindei, p. 215; Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 231; Papazoglu & Speteanu, p. 315. See also Bogdan-Duică, p. 252; Camariano, p. 146; Lecca, p. 9

- ^ Ion & Berindei, pp. 214–215

- ^ a b c Ion & Berindei, p. 215

- ^ Merișescu & Vintilă-Ghițulescu, pp. 35–36

- ^ Merișescu & Vintilă-Ghițulescu, pp. 38–45, 50, 104–110

- ^ Ion & Berindei, pp. 215–216; Merișescu & Vintilă-Ghițulescu, pp. 50–51. See also Lecca, p. 9

- ^ Lecca, pp. 9, 85. See also Tiron, pp. 462, 468, 475, 491

- ^ Crutzescu & Teodorescu, pp. 95, 156; Potra (1990 I), pp. 221, 257, 311, 443; (1990 II), p. 29

- ^ Radu Rosetti, "Arhiva senatorilor dela Chișinău și ocupația rusească dela 1806—1812. III. Amănunte asupra Moldovei dela 1808 la 1812", in Analele Academiei Române, Vol. XXXII, 1909–1910, pp. 199–200, 202, 260–261, 266, 270, 284

- ^ Iorga (1921), p. 284

- ^ Bogdan-Duică, pp. 47, 65, 69

- ^ Dan Simonescu, "Din activitatea tipografică a Bucureștilor (1683–1830)", in Bucureștii Vechi, Vols. I–IV, 1935, p. 134

- ^ Ghica & Roman, pp. 254–256

- ^ Camariano, p. 146

- ^ a b Iorga (1928), p. 419

- ^ Camariano, passim; Dima et al., p. 13

- ^ Camariano, passim; Alexandru Elian, "Introducere", in Alexandru Elian, Nicolae Șerban Tanașoca (eds.), Izvoarele istoriei României, III: Scriitori bizantini (sec. XI–XIV), pp. XVI–XVII, XXVII. Bucharest: Editura Academiei, 1975. OCLC 769301037

- ^ a b c d Camariano, p. 147

- ^ a b c d Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 231

- ^ Cornelia Papacostea-Danielopolu, "La satire sociale-politique dans la littérature dramatique en langue grecque des Principautés (1774—1830)", in Revue Des Études Sud-est Européennes, Vol. XV, Issue 1, January–March 1977, p. 83

- ^ Crutzescu & Teodorescu, p. 216; Ghica & Roman, pp. 90, 254–256

- ^ Șerban, p. 51. See also Bucur, p. 47; Giurescu, p. 111

- ^ Camariano, pp. 146–147

- ^ a b c d Elena D. Gheorghe, Gabriel Stegărescu, "Monografia comunei Bolintinul din Deal", in Sud. Revistă Editată de Asociația pentru Cultură și Tradiție Istorică Bolintineanu, Issues 1–2/2013, pp. 29–30

- ^ Crutzescu & Teodorescu, p. 216; Ghica & Roman, p. 256

- ^ Papazoglu & Speteanu, p. 88

- ^ Gherghe, p. 56

- ^ Papazoglu & Speteanu, pp. 88–90

- ^ Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 77–78

- ^ Iorga (1921), pp. 60, 284; Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 256

- ^ Șerban, pp. 51–52

- ^ Camariano, p. 147; Dima et al., p. 246; Iorga (1921), pp. 65, 284, 341–343; Papazoglu & Speteanu, pp. 87, 90–91, 315

- ^ Bogdan-Duică, pp. 62–63; Crutzescu & Teodorescu, p. 184; Dima et al., p. 246; Papazoglu & Speteanu, p. 315

- ^ Popescu, p. 120

- ^ Vianu & Iancovici, pp. 89–89

- ^ a b Antoine Année (ed.), Le livre noir de Messieurs Delavau et Franchet, ou Répertoire alphabétique de la police politique sous le ministère déplorable, Vol. I, pp. 144–145. Paris: Moutardier, 1829. OCLC 65272072

- ^ Papazoglu & Speteanu, p. 90

- ^ Victor Taki, "Romanian Boyar Opposition to the Organic Statutes: Reasons, Manifestations, Outcomes", in Archiva Moldaviæ, Vol. V, 2013, pp. 212–214

- ^ a b c Crutzescu & Teodorescu, p. 498

- ^ Bucur, p. 44

- ^ Potra (1990 I), p. 484

- ^ Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 50

- ^ Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, pp. 55, 57, 59

- ^ Papazoglu & Speteanu, p. 148; Potra (1990 II), p. 309

- ^ Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 57

- ^ Bogdan-Duică, p. 252; Dima et al., p. 312

- ^ Ghica & Roman, pp. 292–293

- ^ L. Zuckermann, "Amintiri din trecut. Situația comunității bucureștene (2)", in Egalitatea, Issue 14/1898, p. 114

- ^ Ghica & Roman, pp. 422–423. See also Bogdan-Duică, pp. 130–133; Crutzescu & Teodorescu, p. 499; Popescu, pp. 120–121

- ^ Camariano, p. 147; Gherghe, p. 14; Ghica & Roman, p. 436; Potra (1990 I), p. 19

- ^ Daniela Rădescu Predescu, "Aspecte privind emanciparea social-juridică a țiganilor în perioada regulamentară", in Analele Universității din Craiova. Seria Istorie, Vol. XVI, Issue 1, 2011, pp. 73–74

- ^ Bucur, p. 46

- ^ Achim et al., pp. XXII, LII, 63

- ^ a b c Chirică, p. 352

- ^ (in Romanian) Florentin Popescu, "'Nebun n-am fost, dar am căzut pradă...'", in Magazin Istoric, April 2001. See also Chirică, p. 352; Andrei Pippidi, "Casa Prințesei", in Dilema Veche, Issue 194, October 2007

- ^ Ghica & Roman, pp. 422–425

- ^ Bogdan-Duică, p. 252

- ^ Bogdan-Duică, p. 132; Popescu, p. 120

- ^ Popescu, pp. 120–122; Preda, p. 218. See also Bogdan-Duică, pp. 130–133

- ^ Iorga (1929), p. 222

- ^ Bogdan-Duică, p. 244

- ^ "O cotropire de pămênt romănesc. Memoriu", in Adevĕrul, October 30, 1888, p. 2

- ^ Vintilă-Ghițulescu, p. 88. See also Andronescu et al., pp. 88–89

- ^ Vintilă-Ghițulescu, p. 44

- ^ Potra (1963), pp. 163–164

- ^ Andronescu et al., pp. 83–84; Vintilă-Ghițulescu, p. 86

- ^ Ghica & Roman, pp. 293, 438

- ^ Iorga (1929), p. 233

- ^ Ghica & Roman, p. 293

- ^ Vintilă-Ghițulescu, pp. 85–86, 194

- ^ Vintilă-Ghițulescu, p. 86

- ^ Andronescu et al., p. 84

- ^ Iorga (1929), pp. 233–234

- ^ D. Bodin, "Câteva date noi privitoare la familia Sihleanu", in Revista Istorică Română, Vol. III, Issue 1, 1933, pp. 80–81

- ^ "Ujabb tudósítások", in Erdélyi Híradó, July 2, 1841, p. 4

- ^ Cătălina Opaschi, "Un jurnal de călătorie inedit al colonelului Vladimir Moret de Blaremberg", in Muzeul Național, Vol. XVII, 2005, p. 128. See also Păduraru, p. 114

- ^ Andronescu et al., pp. 92–94, 98. See also Bogdan-Duică, pp. 33, 252

- ^ Andronescu et al., p. 94; Camariano, p. 147; Preda, p. 215. See also Iorga (1929), p. 227

- ^ Papazoglu & Speteanu, p. 170

- ^ Andronescu et al., p. 99

- ^ Hugo von Gaudi, "București. Un scurt vademecum pentru germani (II)", in Biblioteca Bucureștilor, Vol. III, Issue 7, 2000, p. 8

- ^ Bibescu, pp. 116–121, 171

- ^ Giurescu, p. 290. See also Bucur, p. 47

- ^ Iorga (1929), pp. 226–227

- ^ Potra (1990 II), p. 245

- ^ Bibescu, pp. 162–169, 567. See also Potra (1990 I), p. 292

- ^ Toma Bulat, "Documentar. Reorganizarea administrativă din 1844 a Țării Românești", in Revista de Istorie, Vol. 27, Issue 10, 1974, pp. 1501–1510

- ^ Bibescu, pp. 96, 98

- ^ Andronescu et al., p. 106. See also Chirică, p. 352; Crutzescu & Teodorescu, p. 499; Lecca, p. 9

- ^ Andronescu et al., p. 107

- ^ "Indidentul din zia de Sf. Filip la Bucureștĭ în 1846", in Adevĕrul, March 11, 1893, p. 2

- ^ Bibescu, p. 581

- ^ Bibescu, pp. 296–297, See also Crutzescu & Teodorescu, p. 499

- ^ Bibescu, pp. 269–270

- ^ Bibescu, pp. 273–277; Potra (1990 I), p. 157

- ^ Potra (1990 I), p. 221

- ^ Bibescu, pp. 241–242. See also Crutzescu & Teodorescu, p. 499

- ^ Bibescu, pp. 588–589

- ^ Bibescu, p. 591

- ^ Bibescu, pp. 593–594

- ^ Potra (1990 I), pp. 531–532

- ^ Petre P. Panaitescu, Contribuții la o biografie a lui N. Bălcescu, p. 47. Bucharest: Convorbiri Literare, 1924. OCLC 876305572

- ^ "Külföld. Oláhország", in Nemzeti, Issue 51/1848, p. 200

- ^ a b c Crutzescu & Teodorescu, p. 499

- ^ Bibescu, pp. 379–380; Crutzescu & Teodorescu, pp. 191, 499. See also Panait & Panait, pp. 92–93; Papazoglu & Speteanu, p. 315; Sumea, pp. 24–26; Totu (1976), p. 54

- ^ Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, p. 169. See also Crutzescu & Teodorescu, p. 191

- ^ a b Doina Pungă, "Repere istorice în memoria artei românești — Revoluția de la 1848", in Muzeul Național, Vol. XX, 2008, p. 94

- ^ a b Papazoglu & Speteanu, p. 315

- ^ Sumea, pp. 25–26. See also Panait & Panait, p. 93

- ^ Panait & Panait, pp. 93–94

- ^ Lăcusteanu & Crutzescu, pp. 171–175; Totu (1976), pp. 54–55. See also Giurescu, p. 136; Sumea p. 26

- ^ Sumea, p. 26

- ^ Elena Condrea, Pârvan Dobrin, "Episoade ale Revoluției de la 1848 din București, în colecția de documente a Direcției Județene Dâmbovița a Arhivelor Naționale", in Curier. Revistă de Cultură și Bibliologie, Vol. IX, Issue 2, 2002, p. 40

- ^ Panait & Panait, pp. 94–95

- ^ Dan Berindei, "Contradicțiile de clasă în desfășurarea revoluției muntene din 1848", in Studii. Revistă de Istorie, Vol. XI, Issue 3, 1958, p. 39

- ^ Xenopol, p. 428

- ^ Potra (1963), pp. 166–168

- ^ Margareta Savin, "Contribuții documentare cu privire la cunoașterea cheltuielilor pentru trupele de ocupație a Bucureștilor în anii 1848—1851", in Muzeul Național, Vol. II, 1975, p. 472

- ^ Iorga (1910), p. 51. See also Crutzescu & Teodorescu, p. 499

- ^ "Nichtamtlicher Theil", in Siebenbürger Bote, Issue 192/1851, p. 937

- ^ L. Botezan, "Problema agrară în dezbaterile parlamentare din Romînia în anul 1862", in Studia Universitatis Babeș-Bolyai. Historia, Vol. IV, Issue 1, 1961, p. 109

- ^ Xenopol, p. 426

- ^ Achim et al., pp. XXXI, LXII, 141

- ^ Iorga (1910), pp. 156–159

- ^ Iorga (1910), pp. 161–164

- ^ Achim et al., pp. 192–193, 196–197, 203–212

- ^ Iorga (1910), pp. 166–167, 187

- ^ Iorga (1929), p. 321

- ^ "Reвicтa", in Zimbrul, Vol. III, Issue 219, October 1855, p. 874

- ^ Gheorghe Sion, Suvenire contimporane, p. 53. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1915. OCLC 7270251

- ^ Achim et al., pp. 222–223

- ^ Ștefan Cazimir, Alfabetul de tranziție, p. 50. Bucharest: Humanitas, 2006. ISBN 973-50-1401-7

- ^ Iorga (1910), p. 187

- ^ Iorga (1928), p. 418

- ^ Teodor Vârgolici, Dimitrie Bolintineanu și epoca sa, p. 158. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1971

- ^ Bibescu, pp. 518–519

- ^ Chirică, pp. 353–354

- ^ "Iassii 13. Noemvrie", in Stéoa Dunărei, Vol. III, Issue 77, November 1858, p. 218

- ^ Ioan C. Filitti, "Ioan Slătineanu—Cel d'intâiu ocărmuitor al Brăilei după 1829 (Notiță biografică)", in Analele Brăilei. Revistă de Cultură Regională, Vol. I, Issues 2–3, March–June 1929, p. 82

- ^ Chirică, p. 354

- ^ Chirică, pp. 354–355

- ^ Chirică, p. 355

- ^ Chirică, pp. 355–356

- ^ Gherghe, p. 170

- ^ Chirică, p. 357

- ^ Iorga (1910), p. 139

- ^ "Politische Rundschau", in Abendblatt des Pester Lloyd, February 11, 1859, p. 2

- ^ I. Mateiu, "Semnificația Unirii", in Conferințele Extensiunii Academice, 1936, pp. 142–143

- ^ Andrei Oțetea, "Însemnătatea istorică a Unirii", in Studii. Revistă de Istorie, Vol. XII, Issue 1, 1959, pp. 36–37

- ^ N. Adăniloaiei, Matei D. Vlad, "Rolul maselor populare în făurirea Unirii Țărilor Romîne", in Studii. Revistă de Istorie, Vol. XII, Issue 1, 1959, p. 96

- ^ Maria Totu, "Masele și Unirea. Ianuarie '59 în București", in Viața Economică, Vol. IV, Issue 2, January 1966, p. 9

- ^ Păduraru, pp. 103–106

- ^ V. Mihodrea, "Frămîntări țărănești după aplicarea reformei agrare. Revoltele de la Mizil, Corbii și Vînătorii Mari, în 1866 și 1867", in Studii. Revistă de Istorie, Vol. XI, Issue 1, 1958, pp. 108–112

- ^ Tiron, pp. 464, 468, 475

- ^ Lecca, p. 9

References

- Venera Achim, Raluca Tomi, Florina Manuela Constantin (eds.), Documente de arhivă privind robia țiganilor. Epoca dezrobirii. Bucharest: Editura Academiei, 2010. ISBN 978-973-27-2014-1

- Șerban Andronescu, Grigore Andronescu (contributor: Ilie Corfus), Insemnările Androneștilor. Bucharest: National History Institute, 1947. OCLC 895304176

- Gheorghe G. Bibescu, Domnia lui Bibescu. Tomul al doilea: Legi și decrete, 1843–1848; Răsvrătirea din 1848: istoria și legenda. Bucharest: Typografia Curții Regale, F. Göbl Fii, 1894.

- Gheorghe Bogdan-Duică, Istoria literaturii române. Întâii poeți munteni. Cluj: Cluj University & Editura Institutului de Arte Grafice Ardealul, 1923. OCLC 28604973

- Bogdan Bucur, "Marea boierime valahă în procesul de tranziție de la 'vechiul regim agrar feudal' la 'era nouă burgheză revoluționară'. O perspectivă critică asupra concepției politice și economice dezvoltată de Ștefan Zeletin", in Tyragetia, Vol. V, 2011, pp. 31–54.

- Nestor Camariano, "Un pretins istoric: Emanuil Băleanu", in Revista Istorică Română, Vol. XVI, Issue 2, 1946, pp. 142–156.

- Nicoleta Chirică, "Căimăcămia de trei din Țara Românească (octombrie 1858–ianuarie 1859)", in Carpica, Vol. XXXVII, 2008, pp. 349–360.

- Gheorghe Crutzescu (contributor: Virgiliu Z. Teodorescu), Podul Mogoșoaiei. Povestea unei străzi. Bucharest: Biblioteca Bucureștilor, 2011. ISBN 978-606-8337-19-7

- Alexandru Dima and contributors, Istoria literaturii române. II: De la Școala Ardeleană la Junimea. Bucharest: Editura Academiei, 1968.

- Cosmin Lucian Gherghe, Emanoil Chinezu – om politic, avocat și istoric. Craiova: Sitech, 2009. ISBN 978-606-530-315-7

- Ion Ghica (contributor: Ion Roman), Opere, I. Bucharest: Editura pentru literatură, 1967. OCLC 830735698

- Constantin C. Giurescu, Istoria Bucureștilor. Din cele mai vechi timpuri pînă în zilele noastre. Bucharest: Editura pentru literatură, 1966. OCLC 1279610

- Narcis Dorin Ion, Dan Berindei, "Familia Berindei. Portretul unor aristocrați ai spiritului. Convorbiri cu academicianul Dan Berindei", in Cercetări Istorice, Vol. XXXIII, 2014, pp. 213–281.

- Nicolae Iorga,

- Viața și domnia lui Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei, domn al Țerii-Romănești (1849–1856). Neamul Românesc: Vălenii de Munte, 1910. OCLC 876302354

- Izvoarele contemporane asupra mișcării lui Tudor Vladimirescu. Bucharest: Librăriile Cartea Românească & Pavel Suru, 1921. OCLC 28843327

- "Cronică", in Revista Istorică, Vol. XIV, Issues 10–12, October–December 1928, pp. 418–448.

- Istoria Românilor prin călători. Volumul 3: De la 1800 până la epoca războiului Crimeii. Bucharest: Editura Casei Școalelor, 1929.

- Grigore Lăcusteanu (contributor: Radu Crutzescu), Amintirile colonelului Lăcusteanu. Text integral, editat după manuscris. Iași: Polirom, 2015. ISBN 978-973-46-4083-6

- Octav-George Lecca, Familii Boierești Române, Seria I. Genealogia a 100 de case din Țara Românească și Moldova. Bucharest, 1911.

- Dimitrie Foti Merișescu (contributor: Constanța Vintilă-Ghițulescu), Tinerețile unui ciocoiaș. Viața lui Dimitrie Foti Merișescu de la Colentina scrisă de el însuși la 1817. Bucharest: Humanitas, 2019. ISBN 978-973-50-6444-0

- Marius Păduraru, "Contribuții la istoricul curții boierești și a bisericii de la Băleni, județul Dâmbovița", in Monumentul (Lucrările Simpozionului Național Monumentul – Tradiție și Viitor, Ediția a XX-a), Part 2, 2019, pp. 97–120

- Ioana Panait, P. I. Panait, "Participarea maselor populare din București în înfrîngerea comploturilor reacțiunii din iunie 1848", in Studii. Revistă de Istorie, Vol. XIII, Issue 6, 1960, pp. 83–98.

- Dimitrie Papazoglu (contributor: Viorel Gh. Speteanu), Istoria fondării orașului București. Istoria începutului orașului București. Călăuza sau conducătorul Bucureștiului. Bucharest: Fundația Culturală Gheorghe Marin Speteanu, 2000. ISBN 973-97633-5-9

- Cristian Tiberiu Popescu, "National Identity versus 'Protective' Power", in Iulian Boldea (ed.), The Proceedings of the International Conference Globalization, Intercultural Dialogue and National Identity. Debates on Globalization. Approaching National Identity through Intercultural Dialogue, pp. 118–122. Târgu-Mureș: Arhipelag XXI, 2015. ISBN 978-606-93692-5-8

- George Potra,

- Petrache Poenaru, ctitor al învățământului în țara noastră. 1799–1875. Bucharest: Editura științifică, 1963.

- Din Bucureștii de ieri, Vols. I–II. Bucharest: Editura științifică și enciclopedică, 1990. ISBN 973-29-0018-0

- Cristian Preda, "Primele alegeri românești", in Studia Politica. Romanian Political Science Review, Vol. 11, Issue 2, 2011, pp. 201–224.

- Constantin Șerban, "Manufactura de basmale (testemeluri) de la Mărcuța (1800—1822)", in București. Materiale de Istorie și Muzeografie, Vol. III, 1965, pp. 43–52.

- N. Stoicescu, Dicționar al marilor dregători din Țara Românească și Moldova. Sec. XIV–XVII. Bucharest: Editura enciclopedică, 1971. OCLC 822954574

- O. Sumea, Ion Constantin Brătianu. Sibiu: Editura Asociațiunii, 1922.

- Tudor-Radu Tiron, "Cimitirul Bellu din București – un ansamblu de heraldică monumentală boierească (a doua jumătate a secolului XIX – prima jumătate a secolului XX)", in Monumentul (Lucrările Simpozionului Național Monumentul – Tradiție și Viitor, Ediția a VIII-a), 2007, pp. 459–491.

- Maria Totu, Garda civică din România 1848—1884. Bucharest: Editura Militară, 1976. OCLC 3016368

- Al. Vianu, S. Iancovici, "O lucrare inedită despre mișcarea revoluționară de la 1821 din țările romîne", in Studii. Revistă de Istorie, Vol. XI, Issue 1, 1958, pp. 67–91.

- Constanța Vintilă-Ghițulescu, Evgheniți, ciocoi, mojici. Despre obrazele primei modernități românești (1750–1860). Bucharest: Humanitas, 2015. ISBN 978-973-50-4881-5

- A. D. Xenopol, "Partidele politice și Revoluția de la 1848 în Principatele Române", in Analele Academiei Române, Vol. XXXII, 1909–1910, pp. 403–457.