Contents

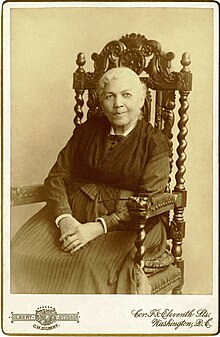

Jean Fagan Yellin (September 19, 1930 – July 19, 2023) was an American historian specializing in women's history and African-American history, and Distinguished Professor Emerita of English at Pace University.[1] She is best known for her scholarship on escaped slave, abolitionist, and author Harriet Jacobs.

Life and career

Yellin was born to Sarah and Peter Fagan. She was married to Ed Yellin and together, they published a memoir entitled In Contempt, Defending Free Speech, Defeating HUAC,[2][3][4] which documented the effect upon their lives of his legal battle for First Amendment rights, even after he had been exonerated by the Supreme Court of the United States. Her children and grandchildren include Peter, Lisa, Michael, David, Amelia, Mosé, Genevra, Benjamin, Sarah, and Blaze.[5]

Yellin received her B.A. from Roosevelt University and an M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Illinois. She began teaching at Pace University in 1968.[1] Her dissertation was published in 1972 as The Intricate Knot: Black Figures in American Literature.[6] She was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in 1990 for Women and Sisters: The Anti-Slavery Feminists in American Culture and won the 2004 Frederick Douglass Prize[1] and the Modern Language Association's William Sanders Scarborough Prize[7] for Harriet Jacobs: A Life.

Scholarship on Harriet Jacobs

Yellin is best known for her research on the former slave Harriet Jacobs and her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Although Incidents had been quite popular at the time of the American Civil War, "by the twentieth century both Jacobs and her book were forgotten".[8]

Prior to Yellin's work in the 1970s-1980s, the accepted academic opinion, voiced by such historians as John Blassingame, was that Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl was a fictional novel written by Lydia Maria Child. While re-reading Incidents in the 1970s as part of a project to educate herself in the use of gender as a category of analysis, Yellin became interested in the question of the text's true authorship. Over the course of a six-year effort, Yellin found and used a variety of historical documents, including from the Amy Post papers at the University of Rochester, state and local historical societies, and the Horniblow and Norcom papers at the North Carolina state archives, to establish both that Harriet Jacobs was the true author of Incidents, and that the narrative was her autobiography, not a work of fiction. At the suggestion of historian Herbert Gutman, she contacted Harvard University Press regarding publication, and her edition of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl was published in 1987 with the endorsement of Professor John Blassingame.[9]

After the publication of Incidents, Yellin engaged in further research which revealed that Jacobs had been well-known in her own time and was very involved in the abolitionist and feminist movements and in relief and education efforts in the South during and after the Civil War. Yellin decided that a biography of Jacobs was needed to "embed her appropriately in American cultural history",[10] and Harriet Jacobs: A Life was published in 2004.

While working on the biography, Yellin also conceived of the idea of the Harriet Jacobs Papers Project, a collection of documents by and about Jacobs. In 2000, an advisory board for the project was established, and after funding was awarded, the project began on a full-time basis in September 2002. Sources of funding included the Carolina State Archives, the University of North Carolina Press, Pace University, the Gladys Delmas Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), and the Center for the Study of the American South. The project won endorsement, and later a grant, from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and was named by the NEH as one of its "We the People" projects. The Harriet Jacobs Papers Project amassed approximately 900 documents by, to, and about Harriet Jacobs, her brother John S. Jacobs, and her daughter Louisa Matilda Jacobs, more than 300 of which were published in 2008 in a two-volume edition entitled The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers. The published edition of the papers is intended for an audience of students, teachers, and scholars from elementary through graduate school, as well as for the general public.[11]

Death

Jean Fagan Yellin died on July 19, 2023, at the age of 92.[12]

Fellowships and grants

- National Museum of American Art of the Smithsonian Institution fellowship [13]

- American Association of University Women Founders Fellowship[13]

- National Humanities Institute of Yale fellowship [13]

- National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship for College Teachers (1986-1987 & 1995) [14][15]

- Research fellowship form the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and the Library Company of Philadelphia (1988) [16]

- Scholar-in-Residency at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library, funded by the Ford Foundation (1989–90)[16]

- Archie K. Davis Fellowship granted by the Carolina Society at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (1991)[16]

- Fellowship at the W.E.B. DuBois Institute for Afro-American Research at Harvard University (1993–94) [16]

- National Historical Publications and Records Commission endorsement (2003) and grant (2004) [17]

- Ford Foundation grant (2004) [18]

Publications

- Yellin, Jean Fagan. The Intricate Knot: Black Figures in American Literature, 1776-1863. New York: New York University Press, 1972. ISBN 978-0-8147-9650-4

- Yellin, Jean Fagan. “Written by Herself: Harriet Jacobs’s Slave Narrative.” American Literature 53 (Nov 1981): 479-486.

- Yellin, Jean Fagan. Women & Sisters: The Antislavery Feminists in American Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-300-04515-4

- Yellin, Jean Fagan. “Through Her Brother’s Eyes: Incidents and “A True Tale.” In Harriet Jacobs and Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: New Critical Essays, ed. Deborah M. Garfield and Rafia Zafar, 44-56. Cambridge Studies in American Literature and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-521-49779-4

- Harriet Jacobs: A Life. Westview Press. 2005. ISBN 978-0-465-09289-5.

- Jean Fagan Yellin, ed. (2009). Incidents in the life of a slave girl : written by herself. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03583-6.

- Jean Fagan Yellin; Cynthia D. Bond, eds. (1991). The pen is ours: a listing of writings by and about African-American women before 1910 with secondary bibliography to the present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506203-8.

- Jean Fagan Yellin; John C. Van Horne, eds. (1994). The Abolitionist sisterhood: women's political culture in Antebellum America. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8011-9.

- Yellin, Jean Fagan, Joseph M. Thomas, Kate Culkin, and Scott Korb, eds. The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers. 2 vols. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8078-3131-1

Reviews

- Lev Grossman (February 2, 2004). "Reader, My Story Ends with Freedom". Time. Archived from the original on March 24, 2005.

- David S. Reynolds (July 11, 2004). "To Be a Slave". the New York Times.

References

- ^ a b c "Pace University - Commencement 2007 - Jean Fagan Yellin". Web.pace.edu. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- ^ Matrullo, Tom, Remembering Ed Yellin, Medium, February 23, 2020

- ^ "In Contempt".

- ^ Lange, Erin, “Who Can Define the Meaning of Un-American?” The Story of Ed Yellin and the Era of Anti-Communism, Department of History, University of Michigan, March 29, 2010

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin, Women & Sisters: The Antislavery Feminists in American Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), Dedication; Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2004), xiii; Yellin, Jean Fagan and others, eds., The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, 2 vols. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), dedication.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2004), 267.

- ^ "Professor Yellin Honored by Modern Language Association". pacepress.org. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2010.

- ^ H.Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Ed. J.F.Yellin, Cambridge 2000, p. xxvii.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2004), xv-xx; Yellin, Jean Fagan and others, eds., The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, 2 vols. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), xxiii.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2004), xx; Yellin, Jean Fagan and others, eds., The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, 2 vols. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), xxiii.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2004), xx, 268; Yellin, Jean Fagan and others, eds., The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, 2 vols. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), xxiv-xxvi, xxix.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin, Who Uncovered a Slavery Tale’s True Author, Dies at 92 (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Jean Fagan Yellin, Women & Sisters: The Antislavery Feminists in American Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), xix.

- ^ "Incidents in the Life of an Abolitionist: The Harriet Jacobs Papers Project". Neh.gov. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2004), xii; Yellin, Jean Fagan and others, eds., The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, 2 vols. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), xxiii.

- ^ a b c d Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2004), xii

- ^ "New York". August 15, 2016.

- ^ "Grant furthers Jacobs Project at Pace". pacepress.org. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2010.

External links

- "Harriet Jacobs website", Yale University

- "The Harriet Jacobs Papers" website, Pace University

- "Professor Sheds Light on Harriet Jacobs' Path to Freedom", NPR

- "Transcript: Interview: Professor Jean Fagan Yellin shares the remarkable story of Harriet Jacobs", NPR, Tavis Smiley, May 4, 2004

- "A Celebration of the Harriet Jacobs Papers", Pace Press, October 7, 2004

- "Up from slavery: Jean Fagan Yellin tells heroic story of former slave Harriet Jacobs", Harvard Gazette

- "Professor's discovery honored by University", Pace Press, November 4, 2008