Contents

Kialo is an online structured debate platform with argument maps in the form of debate trees. It is a collaborative reasoning tool for thoughtful discussion, understanding different points of view, and collaborative decision-making, showing arguments for and against claims underneath user-submitted theses or questions.[2][3][4][5]

The deliberative discourse platform is designed to present hundreds of supporting or opposing arguments in a dynamic argument tree[8] and is streamlined for rational civil debate on topics such as philosophical questions, policy deliberations, entertainment, ethics, science questions, and unsolved problems or subjects of disagreement in general.[3][2][9][10]

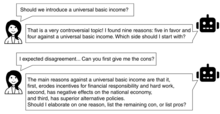

Argument-boxes are structured into hierarchical branches where the root is the main thesis (or theses) of the debate, enabling deliberation and navigable debates between opposing perspectives. A debate is divided into Pro (supporting) and Con (refuting or devaluing) columns where registered users can add arguments and rate the impact on the weight or validity of the parent claim. The arguments are sorted according to the rating average.[15]

Its argument tree structure enables detailed scrutiny of claims at all levels of the tree[16] and allows users to for example quickly understand why a decision was made or which of the aggregated arguments swayed it this way.[3] Newcomers can join a debate at any time and look back at the structured discussion history, and then weigh in at the right place with their new argument or their comment on a specific argument.[2][11][17] The design presets a structure on debates "that allows participants to easily see, process, and ultimately assess the many facets of competing claims".[16]

The word Kialo is Esperanto for "reason".[3][2] The platform is the world's largest argument mapping and structured debate site.[18][19]

Overview

Users can comment on every Pro or Con, for example for requesting sources or expansions.[9] Recent activities of a debate are shown in a panel on the right side of the respective debate.[9] Debates can be found through the search or on the Explore page through their descriptions and topic-tags.[5]

Mere comments that do not make a constructive point (a self-contained argument backed by reasoning) are not allowed and are picked up by other users and moderators.[3][5][20] "Civil language and sensible observations from opposing perspectives" can be seen also in debates about controversial topics.[21] The site by-design incentivizes fair, rigorous, open-minded dialogue.[22] Contributors making claims often also write counterpoints to their own contribution.[3] Claims need to be shorter than 500 characters and can link to external sources.[23]

Debate trees can also start off with multiple theses – such as different policy options or hypotheses. Claims can link to related debates or include segments of them.[24] In the discussion tab of each claim, users can make edit proposals (e.g. for accuracy, improving sources, or changing scope), decide if the argument should be moved or copied to another branch, call for archiving a claim, and ask for extra evidence or clarification.[25]

Debates can grow large and complex for which a sunburst diagram visualization of the topology of the debate[5][26][16][27][28][29] and the search functionality can be useful. Each debate also has a chat-box.[30][31] In cases where e.g. a "Con" is a point against multiple in the "Pros", users – through moderators – can link these arguments at the respective places to avoid duplication of content and allowing a clean chain for people to understand which points are arguments against each other.[9] Contributions of users are tracked, enabling a board of thought-leaders for every debate.[27] Other gamification elements include a feature to thank users for their contributions.[32][23]

The "Perspectives" feature allows users to see 'Impact' ratings of supporters and opposers of a thesis as well as of the debate's moderators and individual contributors.[33] It thereby enables participants to see a debate from other participants' perspectives and to sort by them.[33] In Kialo Edu, this feature lets teachers view votes for a whole class, individuals, or supporters/opponents of a specific thesis.[34] Users in both versions of Kialo can vote on the overall debate topic as well as on individual claims to express their perspectives or conclusions, with the rationale (i.e. the main causal arguments) why they voted on the veracity of the thesis as they did not being captured.[35] Voting can be done by any registered user while navigating through any debate that has voting enabled or via using the Guided Voting wizard user interface that automatically walks through branches.[36]

As of 2021, Kialo doesn't have a mobile app.[37]

Contents

A 2018 report stated the collaborative argument platform hosts more than 10,000 debates in various languages.[23] It also hosts private debates. The website claims that it has over 18,000 public debates as of July 2023, as well as over 1 million votes and over 720,000 claims.[38] Debates can be found via the site's internal search and up to six tags per debate.

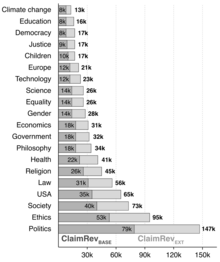

Preprint studies have scraped public debates on over 1.4K issues with over 130K statements as of October 2019[39] and 1628 debates, related to over 1120 categories, with 124,312 unique claims as of June 26, 2020.[10]

Kialo Inc.

The site is run by Kialo Inc. It was founded by German-born entrepreneur and London School of Economics and Political Science graduate Errikos Pitsos in August 2017 and is based in Brooklyn and Berlin.[3][2] According to a 2018 report, the site does not show advertisements and does not sell user's data.[3] The for-profit company was founded in 2011,[40][additional citation(s) needed] Pitsos began to develop the concept in 2012[23] and described various specifics of the system in 2014.[41] In 2018, he stated that they intend to make money by selling the platform to companies as a deliberation and decision-making tool.[23] The site is free to use for the public and in education.[11] According to the site, as of 2023 Kialo.com is a non-revenue generating site with no ads and no reselling of user data.[1]

Applications and adoption

Adopted applications

Applications of its content or the platform in society include:

- Teachers and professors, especially in high schools – including the universities Harvard and Princeton, are using Kialo for class discussions and exercises in critical thinking and reasoning,[3][37][23][17][18][35] as consolidating understanding of materials covered in recent classes,[18] more useful and engaging learning experiences,[35] for remote/e-learning,[42] for clearing up misconceptions,[12] teaching logical fallacies and rational argumentation,[43][44] for academic dialogue,[45] teaching media literacy, and for teaching to sufficiently reflect or research before posting online.[44] Like for debaters of the main site, access for schools and universities is free. Kialo Edu is the custom version of Kialo specifically designed for classroom use where debates are private and locked to invited students.[46][11][47][48][18][49]

- Kialo allows teachers to provide feedback to students on their ideas, argument structure, and research quality while it is left to other students to rate the impacts of their peers' arguments.[11]

- Students can be allowed to contribute anonymously which may be useful for controversial issues as well as for safeguarding privacy in education.[50]

- Students are or can be encouraged to back up their claims with evidence which can foster digital literacy and research skills.[11]

- Students and teachers can use it to arrange their thoughts when structuring an essay or project.[11]

- The site's name was decided on internally using the software.[2]

Prototypical and theoretical applications

Potential, theoretical, prototypical or little-used applications include:

- Education

- Improving critical thinking skills of society at large as well as facilitating deep or efficient thinking and deepening research and debates[2][26][11][17] where e.g. discussions are less shallow[16] and the well-known or many arguments have already been made and in many cases aren't unreasonably over- or underrated.

- Pitsos claimed that "we're training students to be very good test-takers instead of critical thinkers", suggesting teaching people to think things through may be more important or neglected compared to essay writing skills.[2]

- Many young people and adults are "submerged into a sea of dispersed information", "[b]rowsing and engaging in superficial thinking activities". Kialo could counteract this issue and help people develop good sane reasoning.[26]

- Three scholars from three prestigious U.S. universities outlined possible benefits in this domain, including applications beyond higher education such as for academic communication. They suggest the debate platform could be used for structuring the communication of open peer-review by helping those giving feedback to "hone in on[sic] core arguments and pieces of evidence in an even more direct way" than annotated commenting.[26][16]

- It could be used to evaluate extracted argument structures and sequences from raw texts,[16] as in a Semantic Web for arguments. Such "argument mining", to which Kialo is the largest structured source so far, could e.g. be used to assess the completeness and effectiveness of an argumentative discussion[14] or to augment it (with additional arguments, contextual information, assessments, refuting evidence or supporting data).[6]

- A security studies paper suggested it could be used for "managing arguments more effectively than traditional paragraph/bullet-point approaches". It claims that "complexity demands adaptation" but also notes that "Kialo's simplicity does pose some weaknesses and limitations, and in general current systems cannot reliably automate analysis or synthesis of arguments in the same way that statistical packages can automate analysis of data".[52]

- The site could be used by companies and government organizations as "intuitive debate software for internal discussions and decision-making".[3][26]

- It could aid in the search for the best policies and course of action,[16] including for 'wicked problems'[19] and issues where there is a large polarization. This may include "experiments of deliberative democracy inside local governments".[23]

- With a platform like Kialo, users provide "both data on what they see is in the landscape of relevant arguments but also some indication of what they think is important [or has priority] in determining their policy preferences" and "also shows which arguments the individual did not find persuasive, and possibly which rebuttals to a particular argument [was] used to discard it."[16] Current functionality of the site may still be insufficient for the latter outside of experiments.

- It could increase efficiency in knowledge acquisition, including concerning information overload on social media.[14]

- Policy-makers and scientists could use platforms and debates like these to engage with each other as well as the public[24] if they were aware of it and used it. Considering only argument trees beneath theses, its arguments-crowdsourcing and revision principles are not or less vulnerable to framing-issues, intentionally placed attackable segments, weak or missing arguments, straw man points, oversimplification, agenda-setting and other issues that may be common in contemporary public political debates.

- The debate trees can be used to identify arguments that are seen as most credible, as well as reveal which areas of argumentation lack support, precedent, or evidence,[16] which may be useful for subsequent work or more efficient and useful science (as in identifying little-supported assumptions, providing key missing data, or researching key open questions).

- General

- Writers in general, as well as possibly major other opinion leaders, could populate a Kialo debate with their arguments and release it alongside the traditional linear written format,[16] albeit such would mean the arguments would be open to scrutiny, with such being more accessible than large and fans-dominated unstructured comment sections or may already be part of an existing debate tree. They could also use the site in other ways such as for selecting questions to pose to interviewees or for selecting unexplored questions to investigate and report on.

- It could be used for legal cases.[16]

- Websites could embed read-only argument trees (or branches) from the site.[23]

- More broadly, the site's content could be used for reflective brainstorming, and as a crowdsourcing resource for points to use in other media (e.g. long-form text). It enables detailed exploration of some theses or topics as the visual reasoning through tree-based structure allows for many levels of depth and for follow-up questions in the discussion tab of each claim.[25] The founder stated that "The public debates are basically supposed to become a site where people can go and inform themselves. If a debate has over 2,000 unique arguments, it's going to be hard to find an argument that's not in there already. You can go there, similar to Wikipedia, and read."[2]

Research

Kialo is a subject of research studies and its data has been used in research as there are datasets of its contents[5][13][54][10][7] and the site allows exporting CSV files[16] as well as crawling and filtering debates.[6][51]

- Computational research on argumentation

The platform has gained attention in computational research on argumentation because of its high-quality arguments and elaborate argument trees.[14][56] Its data has been used to train and to evaluate natural language processing AI systems such as, most commonly, BERT and its variants.[61] This includes argument extraction, conclusion generation,[58][additional citation(s) needed] argument form quality assessment,[10] machine argumentative debate generation or participation,[6][7][56] surfacing most relevant previously overlooked viewpoints or arguments,[6][7] argumentative writing support[54] (incl. sentence attackability scores),[39] automatic real-time evaluation of how truthful or convincing a sentence is (similar to fact-checking),[39] language model fine tuning[62][56] (incl. chatbots),[63][64] argument impact prediction, argument classification and polarity prediction.[20][65]

- Content analysis in social science and belief studies

The contents can also be analyzed to e.g. show the most common Con rationale-types and factors in general,[39] or reveal the most contested arguments where ratings diverge the most for a given topic.

The site's founder proposed the types of arguments and ways people reason could be investigated as well as the "performance of Kialo versus long-form text in making people change their minds".[2] One study suggests arguers seem to change their viewpoints more readily when a fact they believe has evidence and is undermined when compared to prior beliefs without any specified supporting data.[39]

- The platform as a subject

A study showed that when evaluating policies via Kialo debates, "reading comments from most to least liked, on average, displays more [winning arguments] than reading comments earliest first".[66][67] Kialo has a set of different permissions that participants can have in a given debate. A preprint study makes suggestions regarding "interface design as a scalable solution to conflict management" to prevent adversarial beliefs and values of moderators to have negative impacts on the site.[33]

Reception, motivation and distinction from alternatives

In 2022, MakeUseOf named the site as one of the five best "debate sites to civilly and logically argue online about opinions"[9] and in 2019 as one of the "100+ best websites on the Internet".[68]

- Online discourse quality

The site aims to be a hub for civilized debate where shouting, rudeness or irrationality aren't allowed.[3][23] This has been described as remarkable in an "age of Trumpian tweeting".[3] The site's founder stated that he noticed early on that the Web became "ideal for bad conversations, with prominence given to the most outrageous conversations" and that he "wondered if there wasn't a better method of online discourse", claiming the site's mission is to "empower reason and to make the world more thoughtful",[3][4][69][46] describing it as a "platform where people with opposing views can meet and understand each other's thinking".[70] As of 2023, there are major concerns about online irrational or misinformation-fueled debate – for example, a researcher affirmed[21] that "Twitter was not designed or intended to be a digital town square" as part of a "functioning democracy", addressing Elon Musk's comments about the site in 2022. Instead, she claims it to be a "space for millions of town criers, but not a town square for people to come together and debate".[71] Reports suggest the site may present a more complete and complex view of reality than some other sites where "it's easy to get trapped in echo-chambers of like-minded people where your beliefs are never [meaningfully] challenged" as it shows you "the best arguments on both sides of a debate".[72][24]

- Communication formats

Standard digital formats e.g. "tend to only allow a linear progression of arguments in a stream-of-discussion format".[16] On many websites, "circuitous comment threads [often] render meaningful discussion impossible" and "formats that we use to communicate shape the way we communicate".[2] On the site, users contribute to a debate tree rather than engaging in argumentative back-and-forth commenting.[73]

Kialo may be more appropriate especially for discussions that are relatively complex and hard to visualize or oversee otherwise and allows for public ideation and structured interaction among different types of stakeholders.[24] Linking to supporting evidence is encouraged,[21] but not as strictly required as for example on Wikipedia. Kialo has advantages over structured knowledge bases and Wikipedia in "that it includes many debatable statements; many attacked sentences are subjective judgments, so fact-based knowledge sources may have limited utility".[39] Chains of reasoning can be followed "from beginning to end" with relatively little text to read, nearly no repetition or unexplained statements and without having it derailed by for example "name-calling and directionless ranting".[21] Online debates "have grown so large and acrimonious that no one realistically has the time to read everything and hence get a sense of the actually winning arguments (winners) after all points have been considered" and there is research into how to efficiently calculate the winning arguments or arguments weights and the overall conclusions.[67] Moreover, argumentations on the site are less fleeting and repetitive than debates on social media sites – they are commonly read and actively contributed to over the span of years.[11][2]

- Criticisms and current limitations

One preprint study stated that "[t]hough kialo is designed for scale, and therefore has to be not only robust but also both easy and appealing to use, it has simplified its notion of argument structure so much that there is very little flexibility left. As a commercial entity, its data [not reusable] and platform [not open source] are also closed, making wide-scale application at the science-policy interface more challenging."[74]

One study found that "Kialo's simplicity does pose some weaknesses and limitations" and found the functionality of current systems including Kialo for "synthesis of arguments" to be insufficient.[52] One study suggests the platform is structured in a way that gives insufficient capacity for users to do anything else other than to either agree or disagree with a side,[75] with there e.g. only being options to rate the veracity of the main thesis but not for proposing concrete alternatives and middle-grounds such as more nuanced policies or specifying conditional critical considerations (e.g. exceptions, applicable scopes and limitations) of one's veracity rating of the main thesis, which tend to be very brief and rarely revised.

One study points out that without 'Writer' permissions in a debate, the arguments have "to get past the gatekeepers" of it, which can in some cases be problematic as moderators' beliefs and values may play a role.[33] For instance, such can lead to some users feeling like certain perspectives (or arguments) are being excluded from a debate[33] or getting positioned inappropriately (such as not being visible at the level most relevant). There may be issues relating to framing and argument positioning, whereby for example a false claim (with or without a source) can be added as supporting a thesis which is then only addressed by a later countering claim stating the opposite beneath it – which may reduce the former's 'Impact' rating but is not shown directly at the tree level above as an 'countering' argument. Instead, only the false or weak supporting argument can be seen at the level above in such a case. Impact rating votes do not require reading the arguments beneath but voting can be turned off until the argument map has had time to sufficiently develop.[76]

- Complementarity

The founder clarified key distinctions and complementarity of the site saying "We're going to just be an added place. We're not competing with anybody out there with regards to thoughtful discourse. There are a couple of sites that are question-and-answer sites, or commenting sites, or sharing sites, but there's not a single [major] site for collaborative reasoning — a repository of the why".[2] He states that Wikipedia – another peer production site to which Kialo is sometimes compared with due to argumentative discussions on Talk pages[14] and its public collaborative knowledge integration[33][35] – "tells you the what and we tell you the why".[2]

See also

- Argumentation theory – Academic field of logic and rhetoric

- Collective intelligence – Group intelligence that emerges from collective efforts

- Dialectic – Discursive method of arriving at the truth by way of reasoned contradiction and argumentation

- Evidence-based practices – potential uses

- Public awareness of science – platform use can expose people to most relevant counterarguments and data

- Internet manipulation#Countermeasures – related risks

- Knowledge integration – argument integration

- List of logical fallacies – potential way to classify arguments or removals

- Socratic method – related educational concept

- The medium is the message – importance of platform structure-design

- Causal inference – related to identification of data needs

- r/changemyview – an unstructured debate website

- Project Debater – an AI system

References

- ^ a b "Terms of Service | Kialo". www.kialo.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n June, Audrey Williams (25 March 2018). "How to Promote Enlightened Debate Online". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Margolis, Jonathan (24 January 2018). "Meet the start-up that wants to sell you civilised debate". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ a b "About". Kialo. Archived from the original on 7 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Agarwal, Vibhor; Joglekar, Sagar; Young, Anthony P.; Sastry, Nishanth (25 April 2022). "GraphNLI: A Graph-based Natural Language Inference Model for Polarity Prediction in Online Debates". Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022. pp. 2729–2737. arXiv:2202.08175. doi:10.1145/3485447.3512144. ISBN 9781450390965. S2CID 246867079.

- ^ a b c d e f Bolton, Eric; Calderwood, Alex; Christensen, Niles; Kafrouni, Jerome; Drori, Iddo (2020). "High Quality Real-Time Structured Debate Generation". arXiv:2012.00209 [cs.CL].

- ^ a b c d e Durmus, Esin; Ladhak, Faisal; Cardie, Claire (2019). "The Role of Pragmatic and Discourse Context in Determining Argument Impact". Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP). pp. 5667–5677. arXiv:2004.03034. doi:10.18653/v1/D19-1568. S2CID 202768765.

- ^ Development Co-operation Report 2021 Shaping a Just Digital Transformation: Shaping a Just Digital Transformation. OECD Publishing. 21 December 2021. p. 327. ISBN 978-92-64-85686-8. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "5 Best Debate Sites to Civilly and Logically Argue Online About Opinions". MUO. 14 May 2022. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Skitalinskaya, Gabriella; Klaff, Jonas; Wachsmuth, Henning (2021). "Learning From Revisions: Quality Assessment of Claims in Argumentation at Scale". arXiv:2101.10250 [cs.CL].

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Edwards, Luke (7 July 2021). "What is Kialo? Best Tips and Tricks". TechLearningMagazine. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ a b Allaire, Franklin S.; Killham, Jennifer E. (1 April 2022). Teaching and Learning Online: Science for Elementary Grade Levels. IAP. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-64802-876-2. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ a b Liu, Xin; Ou, Jiefu; Song, Yangqiu; Jiang, Xin (2021). "Exploring Discourse Structures for Argument Impact Classification". arXiv:2106.00976 [cs.CL].

- ^ a b c d e Guo, Zhen; Singh, Munindar P. (2 June 2023). "Representing and Determining Argumentative Relevance in Online Discussions: A General Approach". Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media. 17: 292–302. doi:10.1609/icwsm.v17i1.22146. ISSN 2334-0770. S2CID 259427857. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ [3][9][11][5][12][13][14]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Chaudoin, Stephen; Shapiro, Jacob; Tingley, Dustin (August 2017). "Revolutionizing Teaching and Research with a Structured Debate Platform" (PDF). scholar.harvard.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-06-11. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

- ^ a b c d Mahoney, Jon. "Drawing the Line: Integrating Kialo to Deepen Critical Thinking in Debate". Archived from the original on 2023-06-11. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

- ^ a b c d Ovidiu, Acomi; Nicoleta, Acomi; Roxana, Andrei Elena; Francesca, Dadomo; Domitille, Hocq; Luis, Ochoa Siguencia; Renata, Ochoa-Daderska; Fabiola, Porcelli; Savino, Ricchiuto; Ana, Velasco Garcia (15 May 2022). "Empowering Youth to Critically Analyse Fake News. Strategies of Intervention and Good Practices". doi:10.5281/zenodo.6549573. Archived from the original on 21 July 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c De Liddo, Anna; Strube, Rosa (21 June 2021). "Understanding Failures and Potentials of Argumentation Tools for Public Deliberation". C&T '21: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Communities & Technologies - Wicked Problems in the Age of Tech. Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 75–88. doi:10.1145/3461564.3461584. ISBN 9781450390569. S2CID 235494842.

- ^ a b Agarwal, Vibhor; P. Young, Anthony; Joglekar, Sagar; Sastry, Nishanth (2024). "A Graph-Based Context-Aware Model to Understand Online Conversations". ACM Transactions on the Web. 18: 1–27. arXiv:2211.09207. doi:10.1145/3624579.

- ^ a b c d "Kialo offers online debate where nobody shouts". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ Alfano, Mark; Klein, Colin; Ridder, Jeroen de (29 July 2022). Social Virtue Epistemology. Taylor & Francis. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-000-60730-7. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Four News Startups Trying To Improve Civic Discourse". Nieman Reports. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Debating Solar Geoengineering on the Kialo Visual Reasoning Platform". geoengineering.environment.harvard.edu. 25 September 2018. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ a b [17][35][19][53]

- ^ a b c d e "Developing critical thinking skills with Kialo – Library Trends". TU Delft. 16 January 2018. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Statistics and the Infographic | Kialo Edu Help Center". support.kialo-edu.com. 5 August 2022. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ a b Anastasiou, Lucas; De Liddo, Anna (8 May 2021). "Making Sense of Online Discussions: Can Automated Reports help?". Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 1–7. doi:10.1145/3411763.3451815. ISBN 9781450380959. S2CID 233987842.

- ^ Kiesel, Johannes; Spina, Damiano; Wachsmuth, Henning; Stein, Benno (27 July 2021). "The Meant, the Said, and the Understood: Conversational Argument Search and Cognitive Biases". CUI 2021 - 3rd Conference on Conversational User Interfaces. Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1145/3469595.3469615. ISBN 9781450389983. S2CID 236203094.

- ^ Woodward, Heather; Padfield, Laura (2021). "A Blended Approach to Flipped Learning for Teaching Debate – Using Kialo Edu for EFL Debate Preparation". Journal of Multilingual Pedagogy and Practice. 1. doi:10.14992/00020487.

- ^ "Taking it to Task Volume 5, Issue 1, Summer 2021" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ Feger, Marc (May 2021). "Online argumentation and social media: What they can learn from each other". Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Beck, Jordan; Neupane, Bikalpa; Carroll, John M. "Managing Conflict in Online Debate Communities: Foregrounding Moderators' Beliefs and Values on Kialo". doi:10.31219/osf.io/cdfq7. S2CID 239864855. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Teaching students to take different perspectives with Kialo Edu". 17 May 2023. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Carroll, John M.; Sun, Na; Beck, Jordan (2019). "Creating Dialectics to Learn: Infrastructures, Practices, and Challenges". Learning in a Digital World: Perspective on Interactive Technologies for Formal and Informal Education. Springer. pp. 37–58. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-8265-9_3. ISBN 978-981-13-8265-9. S2CID 195785108. Archived from the original on 2023-06-11. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

- ^ "Guided Voting | Kialo Help Center". support.kialo.com. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Debating the Issues with Kialo | ETEC523: Mobile and Open Learning". blogs.ubc.ca. University of British Columbia. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ "Explore Popular Debates, Discussions and Critical Thinking…". Kialo. Archived from the original on 18 July 2023. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Jo, Yohan; Bang, Seojin; Manzoor, Emaad; Hovy, Eduard; Reed, Chris (2020). "Detecting Attackable Sentences in Arguments". arXiv:2010.02660 [cs.CL].

- ^ "Kialo - Products, Competitors, Financials, Employees, Headquarters Locations". CB Insights. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ "US Patent Application for Management, Evaluation And Visualization Method, System And User Interface For Discussions And Assertions Patent Application (Application #20150220580 issued August 6, 2015) - Justia Patents Search". patents.justia.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ Mishra, Lokanath; Gupta, Tushar; Shree, Abha (2020). "Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic". International Journal of Educational Research Open. 1: 100012. doi:10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100012. PMC 7832355. PMID 35059663.

- ^ Wasson, Barbara; Zörgő, Szilvia (11 January 2022). Advances in Quantitative Ethnography: Third International Conference, ICQE 2021, Virtual Event, November 6–11, 2021, Proceedings. Springer Nature. p. 34. ISBN 978-3-030-93859-8. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ a b Schiebenes, Pascal (1 November 2022). Digitale Medien für den Unterricht: Deutsch: 30 innovative Unterrichtsideen (in German). Klett / Kallmeyer. p. 54. ISBN 978-3-617-92409-9. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ Blackburn, Barbara R. (16 September 2020). "Demonstrating Learning in the Remote Classroom". Rigor in the Remote Learning Classroom: Instructional Tips and Strategies. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-24635-3. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ a b Mills, Afrika Afeni (16 June 2022). Open Windows, Open Minds: Developing Antiracist, Pro-Human Students. Corwin Press. ISBN 978-1-0718-8702-8. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ Butcher, Charity. "Creating Online Debates Using Kialo Edu" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ Lang-Raad, Nathan D. (18 April 2023). Never Stop Asking: Teaching Students to be Better Critical Thinkers. John Wiley & Sons. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-119-88754-6. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ "Try Out a Kialo Classroom Debate for High School | Kialo Edu Help Center". support.kialo-edu.com. 5 August 2022. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ "How students can benefit from Anonymous Discussions". 8 May 2023. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ a b c Betz, Gregor (2022). "Natural-Language Multi-Agent Simulations of Argumentative Opinion Dynamics". Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation. 25: 2. arXiv:2104.06737. doi:10.18564/jasss.4725. S2CID 233231231.

- ^ a b "Complexity Demands Adaptation: Two Proposals for Facilitating Better Debate in International Relations and Conflict Research". Georgetown Security Studies Review. 30 November 2022. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ Popescu, C.; Cocarascu, O.; Toni, F. (15 December 2018). "A platform for crowdsourcing corpora for argumentative". The International Workshop on Dialogue, Explanation and Argumentation in Human-Agent Interaction (DEXAHAI). hdl:10044/1/71110. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d Skitalinskaya, Gabriella; Wachsmuth, Henning (2023). "To Revise or Not to Revise: Learning to Detect Improvable Claims for Argumentative Writing Support". arXiv:2305.16799 [cs.CL].

- ^ a b Durmus, Esin; Ladhak, Faisal; Cardie, Claire (2019). "Determining Relative Argument Specificity and Stance for Complex Argumentative Structures". Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. pp. 4630–4641. arXiv:1906.11313. doi:10.18653/v1/P19-1456. S2CID 195699602.

- ^ a b c d Al Khatib, Khalid; Trautner, Lukas; Wachsmuth, Henning; Hou, Yufang; Stein, Benno (August 2021). "Employing Argumentation Knowledge Graphs for Neural Argument Generation" (PDF). Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics. pp. 4744–4754. doi:10.18653/v1/2021.acl-long.366. S2CID 236460348. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-04-08. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

- ^ Prakken, H.; Bistarelli, S.; Santini, F. (25 September 2020). Computational Models of Argument: Proceedings of COMMA 2020. IOS Press. ISBN 978-1-64368-107-8. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ a b Alshomary, Milad; Wachsmuth, Henning (2023). "Conclusion-based Counter-Argument Generation". arXiv:2301.09911 [cs.CL].

- ^ Thorburn, Luke; Kruger, Ariel (2022). "Optimizing Language Models for Argumentative Reasoning" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-03-28. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Jo, Yohan; Bang, Seojin; Reed, Chris; Hovy, Eduard (2 August 2021). "Classifying Argumentative Relations Using Logical Mechanisms and Argumentation Schemes". Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 9: 721–739. arXiv:2105.07571. doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00394. S2CID 234742133.

- ^ [5][57][58][59][54][55][6][60][7][56]

- ^ Fanton, Margherita; Bonaldi, Helena; Tekiroglu, Serra Sinem; Guerini, Marco (2021). "Human-in-the-Loop for Data Collection: a Multi-Target Counter Narrative Dataset to Fight Online Hate Speech". Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). pp. 3226–3240. arXiv:2107.08720. doi:10.18653/v1/2021.acl-long.250. S2CID 236087808.

- ^ Björklin, Hampus; Abrahamsson, Tim; Widenfalk, Oscar (2021). "A retrieval-based chatbot's opinion on the trolley problem". Archived from the original on 2023-06-11. Retrieved 2023-06-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Farag, Youmna; Brand, Charlotte O.; Amidei, Jacopo; Piwek, Paul; Stafford, Tom; Stoyanchev, Svetlana; Vlachos, Andreas (2023). "Opening up Minds with Argumentative Dialogues". arXiv:2301.06400 [cs.CL].

- ^ Lenz, Mirko; Sahitaj, Premtim; Kallenberg, Sean; Coors, Christopher; Dumani, Lorik; Schenkel, Ralf; Bergmann, Ralph (2020). "Towards an Argument Mining Pipeline Transforming Texts to Argument Graphs". IOS Press: 263–270. arXiv:2006.04562. doi:10.3233/FAIA200510. S2CID 219531343.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Young, Anthony P.; Joglekar, Sagar; Boschi, Gioia; Sastry, Nishanth (1 January 2021). "Ranking comment sorting policies in online debates". Argument & Computation. 12 (2): 265–285. doi:10.3233/AAC-200909. ISSN 1946-2166. S2CID 228956951.

- ^ a b Young, Anthony P. "Likes as Argument Strength for Online Debate" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ "The 100+ Best Websites on the Internet". MUO. 30 November 2019. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ Killenberg, G. Michael; Anderson, Rob (20 February 2023). Democracy's News: A Primer on Journalism for Citizens Who Care about Democracy. University of Michigan Press. p. 383. ISBN 978-0-472-05584-5. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ "xpmethod | Group for experimental methods in the humanities". xpmethod.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2023-06-11. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ Maddox, Jessica. "Elon Musk's comments about Twitter don't square with the social media platform's reality". techxplore.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ "10 Websites That Will Give You Superpowers". Inc.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ "Debate as pedagogy: Practices, tools, and examples from Harvard faculty – Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching (HILT)". hilt.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

Kialo, where students make "claims" about a thesis, contributing to a visual debate tree that empowers reason rather than argumentative commenting

- ^ Hahn, Ulrike; Jens Koed Madsen; Reed, Chris (2022). "Managing Expert Disagreement for the Policy Process and Beyond". arXiv:2212.14714 [cs.CY].

- ^ Althuniyan, Najla; Sirrianni, Joseph W.; Rahman, Md Mahfuzer; Liu, Xiaoqing "Frank" (2019). Design of Mobile Service of Intelligent Large-Scale Cyber Argumentation for Analysis and Prediction of Collective Opinions. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 11516. Springer International Publishing. pp. 135–149. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-23367-9_10. ISBN 978-3-030-23366-2. S2CID 195353310.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "Using Voting | Kialo Help Center". support.kialo.com. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

External links

- Kialo Edu blog, guides and ideas for applications in education

- Kialo on Twitter

- Structured online debate and conclusion-making, images and related projects

- The Role of Pragmatic and Discourse Context in Determining Argument Impact, 2019, R&D on determining argument impact