Contents

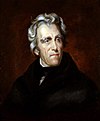

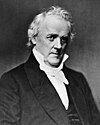

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782 – June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He was also the 1848 Democratic presidential nominee. A slave owner himself,[1] he was a leading spokesman for the doctrine of popular sovereignty, which at the time held the idea that people in each U.S state should have the right to decide on whether to permit or prohibit slavery, believing in the idea of states rights.

Born in Exeter, New Hampshire, he attended Phillips Exeter Academy before establishing a legal practice in Zanesville, Ohio. After serving in the Ohio House of Representatives, he was appointed as a U.S. Marshal. Cass also joined the Freemasons and would eventually co-found the Grand Lodge of Michigan. He fought at the Battle of the Thames in the War of 1812 and was appointed to govern Michigan Territory in 1813. He negotiated treaties with American tribes to open land for American settlement as part of the belief in the 19th century phrase “manifest destiny” at the time, and led a survey expedition into the northwest part of the territory.

Cass resigned as governor in 1831 to accept appointment as Secretary of War under Andrew Jackson. As Secretary of War, he helped implement Jackson's policy of Indian removal. After serving as ambassador to France from 1836 to 1842, he unsuccessfully sought the presidential nomination at the 1844 Democratic National Convention; a deadlock between supporters of Cass and former President Martin Van Buren ended with the nomination of James K. Polk. In 1845, the Michigan Legislature elected Cass to the Senate, where he served until 1848. Cass's nomination at the 1848 Democratic National Convention precipitated a split in the party, as Cass's advocacy for popular sovereignty alienated the anti-slavery wing of the party. Van Buren led the Free Soil Party's presidential ticket and appealed to many anti-slavery Democrats, possibly contributing to the victory of Whig nominee Zachary Taylor.

Cass returned to the Senate in 1849 and continued to serve until 1857 when he accepted appointment as the Secretary of State. He unsuccessfully sought to buy land from Mexico and sympathized with American filibusters in Latin America. Cass resigned from the Cabinet in December 1860 in protest of Buchanan's handling of the threatened secession of several Southern states. Since his death in 1866, he has been commemorated in various ways, including with a statue in the National Statuary Hall.

Early life

Cass was born on October 9, 1782, in Exeter, New Hampshire, near the end of the American Revolution. His parents were Molly (née Gilman) Cass and Major Jonathan Cass, a Revolutionary War veteran who fought under General George Washington at Bunker Hill.[2]

Cass attended the private Phillips Exeter Academy. In 1800, the family moved to Marietta, Ohio, part of a wave of westward migration after the end of the war and defeat of Native Americans in the Northwest Indian War. Cass studied law with Return J. Meigs Jr., was admitted to the bar, and began a practice in Zanesville.

Beginning of Cass's career

In 1806, Cass was elected to the Ohio House of Representatives. The following year, President Thomas Jefferson appointed Cass as the U.S. Marshal for Ohio.[3]

He joined the Freemasons, an increasingly popular fraternal organization in that period, being initiated as an Entered Apprentice in what was later American Union Lodge No.1 at Marietta on December 5, 1803.[4] He achieved his Fellow Craft degree on April 2, 1804, and his Master Mason degree on May 7, 1804. On June 24, 1805, he was admitted as Charter member of the Lodge of Amity 105 (later No.5), Zanesville. He served as the first Worshipful Master of the Lodge of Amity in 1806.[4] Cass was one of the founders of the Grand Lodge of Ohio, representing the Lodge of Amity at the first meeting on January 4, 1808. He was elected Deputy Grand Master on January 5, 1809, and Grand Master on January 3, 1810, January 8, 1811, and January 8, 1812.[4]

War of 1812

Engagement at bridge near Fort Malden

When the War of 1812 began against the United Kingdom, Cass took command of the 3rd Ohio Volunteer Regiment. In America's invasion of Canada, Cass conducted military operations in Canada. On July 16, 1812, a contingent of the British 41st Regiment – about 60 militia troops and some Indians – were posted near a bridge near British Fort Malden. Cass and Army Colonel James Miller with their troops were in concealed positions. The British detected the American reconnaissance force commanded by Cass and Miller. The British sent a party of Indians over the bridge to draw the Americans out; however, once the Indians crossed, the concealed Americans opened fire wounding two Indians and killing one. The American officers send word to allow the American reconnaissance force to take the fort and hold it until reinforcements arrived. But American commander Hull was very unsupportive and indecisive of this opportunity. So the reconnaissance force under Cass and Miller withdrew back to American lines.[5]

Second engagement at bridge near Fort Malden

On July 19, 1812, Colonel Duncan McArthur with a reconnaissance force combined with 150 Ohio infantry troops under Cass were near the bridge leading to Fort Malden. Two British artillery guns fired on the Americans and took out an American cannon. Cass and his fellow Americans captured two British troops after they crossed the bridge. All of the Americans safely withdrew with their prisoners.[6]

Hit-and-run attack on bridge at the Riviere aux Canards

On July 28, 1812, Colonel Cass conducted a hit-and-run attack at the Rivière aux Canards driving back a band of Native Americans. The Americans killed one Native American and scalped him. Cass and his fellow Americans then withdrew safely.[7]

Battle of the Thames

Cass became colonel of the 27th United States Infantry Regiment on February 20, 1813. Soon after, he was promoted to brigadier general in the Regular Army on March 12, 1813. Cass took part in the Battle of the Thames, a defeat of British and Native American forces. Cass resigned from the Army on May 1, 1814.

Territorial Governor of Michigan

As a reward for his military service, Cass was appointed Governor of the Michigan Territory by President James Madison on October 29, 1813, serving until 1831. As he was frequently traveling on business, several territorial secretaries often acted as governor in his place. During this period, he helped negotiate and implement treaties with Native American tribes in Michigan, by which they ceded substantial amounts of land. Some were given small reservations in the territory.

In 1817, Cass was one of the two commissioners (along with Duncan McArthur), who negotiated the Treaty of Fort Meigs, which was signed on September 29 with several Native American tribes of the region, under which they ceded large amounts of territory to the United States.[8] This helped open up areas of Michigan to settlement by Euro-Americans. That same year, Cass was named to serve as Secretary of War under President James Monroe, but he declined the appointment.

In 1820, Cass led an expedition to the northwestern part of Michigan Territory, in the Great Lakes region in today's northern Minnesota. Its purpose was to map the region and locate the source of the Mississippi River. The headwater of the great river was then unknown, resulting in an undefined border between the United States and British North America, which had been linked to the river. The Cass expedition erroneously identified what became known as Cass Lake as the Mississippi's source. It was not until 1832 that Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, the Cass expedition's geologist, identified nearby Lake Itasca as the headwater of the Mississippi.

Though the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territory, which included what later became Michigan Territory, a small number of slaves continued to reside in Michigan until it achieved statehood.[9] Despite his later claims to the contrary, as territorial governor, Cass is known to have owned at least one slave, a household servant, as evidenced by 1818 correspondence between him and Alexander Macomb.[10] Slavery continued in Michigan until admission to the Union in 1837, when its first state constitution outlawed slavery statewide.[9]

Secretary of War and expediter of Indian removal

In 1830, Cass published an article in the North American Review that argues passionately that Indians are inherently inferior to whites, and incapable of being civilized and thus should be removed from the eastern United States.[11] This article caught the attention and approval of Andrew Jackson. On August 1, 1831, Cass resigned as governor of the Michigan Territory to take the post of Secretary of War under President Andrew Jackson, a position he would hold until 1836. Cass was a central figure in implementing the Indian removal policy of the Jackson administration; Congress had passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830. While it was directed chiefly against the Southeastern tribes, especially the Five Civilized Tribes, it also affected tribes in Ohio, Illinois, and other areas east of the Mississippi River. Most were forced to Indian Territory in present-day Kansas and Oklahoma, but a number of bands negotiated being allowed to remain in Michigan.[2]

U.S. Minister to France

At the end of his term, President Jackson appointed Cass to succeed Edward Livingston as the U.S. Minister to France on October 4, 1836. He presented his credentials on December 1, 1836, and served until he left his post on November 12, 1842, when he was succeeded by William R. King, who later became the 13th Vice President of the United States under President Franklin Pierce.

Presidential ambitions and U.S. Senate

In the 1844 Democratic convention, Cass stood as a candidate for the presidential nomination, losing on the 9th ballot to dark horse candidate James K. Polk.

Cass was elected by the state legislature to represent Michigan in the United States Senate, serving in 1845–1848. He served as chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs in the 30th Congress.

In 1848, he resigned from the Senate to run for president in the 1848 election. William Orlando Butler was selected as his running mate.[12] Cass was a leading supporter of the doctrine of popular sovereignty, which held that the American citizens who lived in a territory should decide whether to permit slavery there.[13] His nomination caused a split in the Democratic Party, leading many antislavery Northern Democrats to join the Free Soil Party, which nominated former President Martin Van Buren.

After losing the election to Zachary Taylor, Cass was returned by the state legislature to the Senate, serving from 1849 to 1857. He was the first non-incumbent Democratic presidential candidate to lose an election and the first Democrat who was unsuccessful in his bid to succeed another Democrat as president. Apart from James Buchanan's election to succeed Franklin Pierce in 1856, subsequent Democrats who attempted election to succeed another Democrat as president all failed in their bid to do so.

Cass made another bid for president in 1852 but neither he nor rival Democratic contenders Buchanan and Stephen Douglas secured a majority of delegates’ votes at the Democratic Convention in Baltimore, and the party went with Franklin Pierce instead.

U.S. Secretary of State

On March 6, 1857, President James Buchanan appointed Cass to serve as Secretary of State as a consolation prize for his previous presidential runs. Although retaining incumbent Secretary of State William L. Marcy was considered the best option by many, Buchanan made it clear that he did not want to keep anyone from the Pierce Administration. Moreover, Marcy had opposed his earlier presidential bids, and was in poor health in any event, ultimately dying in July 1857. Cass, aged 75, was seen by most as too old for such a demanding position and was thought to likely be little more than a figurehead. Buchanan, weighing many of the other options for Secretary of State, considered that Cass was the best choice to avoid political infighting and sectional tensions. Buchanan wrote a flattering letter offering him the post of Secretary of State, commenting that he was remarkably active and energetic for his advanced age. Cass, who was retiring from the Senate, but not eager to leave Washington and return home to Michigan, immediately accepted.

Taking the position, Cass promised to refrain from making anti-British remarks in public (having served in the War of 1812, Cass had a low opinion of London). Most assumed Cass was a temporary Secretary of State until a younger, more fit man could be found, however, he ultimately served for all but the final four months of Buchanan's administration. As expected, the aged Cass largely delegated major decision-making to subordinates, but eagerly signed his name on papers and dispatches penned by them.[8]

While sympathetic to American filibusters in Central America, he was instrumental in having Commodore Hiram Paulding removed from command for his landing of Marines in Nicaragua and compelling the extradition of William Walker to the United States.[14] Cass attempted to buy more land from Mexico, but faced opposition from both Mexico and congressional leaders. He also negotiated a final settlement to the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty, limiting U.S. and British control of Latin American countries.[3] The chiefs of Raiatea and Tahaa in the South Pacific, refusing to accept the rule of King Tamatoa V, unsuccessfully petitioned the United States to accept the islands under a protectorate in June 1858.[15]

Cass resigned on December 14, 1860, because of what he considered Buchanan's failure to protect federal interests in the South and failure to mobilize the federal military, actions that might have averted the threatened secession of Southern states.[16]

Personal life

On May 26, 1806, Cass married Elizabeth Spencer (1786–1853), the daughter of Dr. Joseph Spencer Jr. and Deborah (née Seldon) Spencer.[8] Her paternal grandfather was Joseph Spencer, a Continental Congressman who was a major general in the Continental Army.[17] Lewis and Elizabeth were the parents of seven children, five of whom lived past infancy:[18]

- Isabella Cass (1805–1879), who married Theodorus Marinus Roest van Limburg, a Dutch journalist, diplomat, and politician.[19]

- Elizabeth Selden Cass (1812–1832)[19]

- Lewis Cass Jr. (1814–1878), who served as an army officer and as U.S. Chargé d'Affaires and Minister to the Papal States.[19]

- Mary Sophia Cass (1812–1882), who married Army officer Augustus Canfield, an officer of the Corps of Topographical Engineers.[19]

- Matilda Frances Cass (1818–1898), who married Henry Ledyard, the mayor of Detroit.[19]

- Ellen Cass (1821–1824), who died young.[19]

- Spencer Cass (1828-1828), who died in infancy.[19]

Cass died on June 17, 1866, in Detroit, Michigan. He is buried in Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit.

Descendants

Through his daughter Mary, he was the great-grandfather of Cass Canfield (longtime president and chairman of Harper & Brothers, later Harper & Row).[20]

Through his daughter Matilda, he was the grandfather of Elizabeth Cass Ledyard (wife of Francis Wayland Goddard);[21] Henry Brockholst Ledyard Jr. (who was president of the Michigan Central Railroad);[22][23] Susan Livingston Ledyard (wife of Hamilton Bullock Tompkins);[24] Lewis Cass Ledyard (a prominent lawyer with Carter Ledyard & Milburn who was the personal counsel of J. Pierpont Morgan);[25][26] and Matilda Spancer Ledyard.[27]

Cass's great-great-grandson, Republican Thomas Cass Ballenger, represented North Carolina's 10th Congressional District from 1986 to 2005.[28]

Monuments and Commemoration

- A statue of Lewis Cass is one of the two that were submitted by Michigan to the National Statuary Hall collection in the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. It stands in the National Statuary Hall room.[29]

- The Liberty ship SS Lewis Cass[30]

- He is the eponym of the village of Casstown, Ohio,[31] the community of Cassville, West Virginia,[32] Cassopolis, Michigan, and Cass County, Michigan, as well as Cass City, Michigan, and the Cass River that runs around the surrounding area.

- Cass Avenue in Detroit.[33] Cass Avenue in Mt. Clemens.[34]

- The Lewis Cass Legacy Society, which supports The Michigan Masonic Charitable Foundation, was named for his support of Michigan Freemasonry.[35]

- Bartow County, Georgia, was originally named Cass County after Lewis Cass, but was changed in 1861 after Francis Bartow died as a Confederate war hero and due to Cass's alleged opposition to slavery, even though he was an advocate of states' rights via the doctrine of popular sovereignty. Cassville, Georgia is an unincorporated community in the same county, was originally the county seat before the name was changed from Cass County. The seat was moved to Cartersville, Georgia after General Sherman destroyed Cassville in his Atlanta Campaign of 1864.

- Cass Technical High School in Detroit, Cass High School in Bartow County, Georgia, Lewis Cass High School in Walton, Indiana, and Lewis Cass Elementary in Livonia, Michigan, were named in honor of Lewis Cass.

- Cass Street in Milwaukee, WI was named in honor of Lewis Cass.[36]

- The Lewis Cass Building, a principal state office building in the Lansing, Michigan capitol government complex. It was renamed on June 30, 2020, to the Elliott-Larsen Building.[37]

- Lewis Cass is the namesake of counties in the following states: Indiana, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Illinois, Michigan, and Texas. However, Cass County, North Dakota, was named for his nephew.

- Lewis Cass is the namesake of Cass Street in Green Bay, Wisconsin.

- Cass Street in Monroe, Michigan, was named in honor of Lewis Cass. (However, Cass Street in Traverse City, Michigan, and in Cadillac, Michigan, were named for his nephew, George Washington Cass.)

Other honors and memberships

- Elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1820.[38]

- Elected a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1826.[39]

Publications

- Cass, Lewis (1840). France, its King, Court and Government. New York: Wiley and Putnam.

See also

References

- ^ "Congress slaveowners", The Washington Post, 2022-01-13, retrieved 2022-07-04

- ^ a b "Lewis Cass - People - Department History". history.state.gov. Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs United States Department of State. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Biographies of the Secretaries of State: Lewis Cass (1782–1866)". Office of the Historian. U.S. State Department. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ a b c "Past Grand Masters - 1810 Lewis Cass". Grand Lodge of Ohio. Archived from the original on 2016-09-21. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ^ "The War of 1812: A Complete Chronology with Biographies of 63 General Officers" by Bud Hannings Page.38.

- ^ "The War of 1812: A Complete Chronology with Biographies of 63 General Officers" by Bud Hannings Page.39.

- ^ "The War of 1812: A Complete Chronology with Biographies of 63 General Officers" by Bud Hannings Page.42.

- ^ a b c Heidler, David S., and Heidler, Jeanne T. (eds) (2004). Encyclopedia of the War of 1812, pp. 83-84. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-362-4.

- ^ a b "Anti-Slavery Movement in Michigan". Michiganology.org. Lansing, MI: Michigan History Center. 2023. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ Klunder, Willard Carl (1996). Lewis Cass and the Politics of Moderation. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0-8733-8536-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lewis Cass. Removal of the Indians

- ^ Kleber, John E. (ed.) (1992). The Kentucky Encyclopedia, p. 146. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0, ISBN 978-0-8131-1772-0.

- ^ Klunder (1996), pp. 266–67

- ^ "Collier, Ellen C. (1993) "Instances of Use of United States Forces Abroad, 1798 - 1993" CRS Issue Brief Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, Washington DC". Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ Flude, Anthony G. (March 2012). "Manuscript XXIII: A Raiatean Petition for American Protection". The Journal of Pacific History. 47 (1). Canberra: Australian National University: 111–121. doi:10.1080/00223344.2011.632982. OCLC 785915823. S2CID 159847026.

- ^ Cass’s resignation statement, quoted in McLaughlin, Andrew Cunningham (1899) Lewis Cass Houghton, Mifflin, Boston, pp. 345–346, OCLC 4377268, (standard library edition, first edition was published in 1891)

- ^ Whittelsey, Charles Barney. "Historical Sketch of Joseph Spencer - Sons of the American Revolution, Connecticut". www.connecticutsar.org. Historian Society of the Sons of the Revolution in the State of Connecticut. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Burton, Clarence Monroe; et al. (1922). The City of Detroit, Michigan, 1701–1922. Vol. 2. Detroit, MI: S. J. Publishing Company. p. 1367.

- ^ a b c d e f g The City of Detroit, Michigan, 1701-1922, p. 1367.

- ^ "Cass Canfield, a Titan of Publishing, Is Dead at 88". The New York Times. 28 March 1986. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Island, National Society of the Colonial Dames of America Rhode (1897). First record book of the Society of Colonial Dames in the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations: Ending August 31, 1896. Snow & Farnham, printers. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Clarence Monroe Burton; William Stocking; Gordon K. Miller (1922), The city of Detroit, Michigan, 1701-1922; Volume 4, The S. J. Clarke publishing company, pp. 5–6

- ^ "Ledyard Given Quiet Funeral," Detroit Free Press, May 28, 1921, pg. 11.

- ^ Tompkins, Hamilton Bullock (1877). Biographical Record of the Class of 1865, of Hamilton College. Hamilton College. p. 73. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Psi Upsilon (1932), The diamond of Psi Upsilon, vol. 18, Psi Upsilon Fraternity, pp. 170–171

- ^ Marquis, Albert Nelson (1911). Who's Who in America | A Biographical Directory of Notable Living Men and Women of The United States | Vol VI 1910-1911. London: A. N. Marquis & Co. p. 1134. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Ledyard, Henry. "Guide to the Henry Ledyard collection 1726-1899 and undated (bulk 1840-1859)" (PDF). library.brown.edu. Redwood Library and Athenaeum. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ United States Congress (2005). Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774–2005. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 604. ISBN 978-0-16-073176-1.

- ^ "Lewis Cass statue, Statuary Hall, the Capitol at Washington". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

- ^ "Michigan Military and Vetarans Hall of Honor | Lewis Cass". www.mimilitaryvethallofhonor.org. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

- ^ The History of Miami County, Ohio: Containing a History of the County; Its Cities, Towns, Etc. Windmill Publications. 1880. p. 396.

- ^ Kenny, Hamill (1945). West Virginia Place Names: Their Origin and Meaning, Including the Nomenclature of the Streams and Mountains. Piedmont, WV: The Place Name Press. p. 159.

- ^ www.mapquest.com https://www.mapquest.com/us/mi/detroit/48226/grand-river-ave-and-cass-ave-42.334536,-83.054404. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Cass Ave · Mt Clemens, MI". Cass Ave · Mt Clemens, MI. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

- ^ "Michigan Masonic Legacy Society Gala - Michigan Masons". michiganmasons.org. 2019-11-27. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

- ^ "Welcome to Cass Street". VoiceMap. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

- ^ Haddad, Ken (2020-06-30). "Michigan governor: Lansing's Lewis Cass Building renamed to 'Elliott-Larsen Building'". WDIV. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

- ^ "MemberListC | American Antiquarian Society". www.americanantiquarian.org. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2021-04-06.

Bibliography

- United States Congress. "Lewis Cass (id: C000233)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Klunder, Willard Carl. ”Lewis Cass, Stephen Douglas, and Popular Sovereignty: The Demise of Democratic Party Unity,” in Politics and Culture of the Civil War Era ed by Daniel J. McDonough and Kenneth W. Noe, (2006) pp. 129–53

- Klunder, Willard Carl (1991). "The Seeds of Popular Sovereignty: Governor Lewis Cass and Michigan Territory". Michigan Historical Review. 17 (1): 64–81. doi:10.2307/20173254. JSTOR 20173254.

- Silbey, Joel H. Party Over Section: The Rough and Ready Presidential Election of 1848 (2009), 205 pp.

- Bell, William Gardner (1992). "Lewis Cass". Secretaries of War and Secretaries of the Army. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH pub 70-12. Archived from the original on 2007-12-14. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- Elmwood Cemetery Biography Archived 2009-01-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Cleland, Charles E. ”Rites of Conquest: The History and Culture of Michigan's Native Americans”. University of Michigan Press (1992).

External links

- Lewis Cass papers, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

- Lewis Cass at Find a Grave