Contents

St. Stephen's Church, Coleman Street, also called "St Stephen's in the Jewry", was a church in the City of London, at the corner of Coleman Street and what is now Gresham Street (and in Coleman Street Ward), first mentioned in the 12th century. In the middle ages it is variously described as a parish church, and as a chapel of ease to the church of St Olave Old Jewry; its parochial status was defined (or re-established) permanently in 1456.

The body of the medieval church was destroyed in the Great Fire of London of 1666, and was replaced with a new structure by the office of Sir Christopher Wren.[1] This second church was destroyed by bombing in 1940 and was not rebuilt after the War.[2] Substantial records survive for the church and parish, including churchwardens' accounts (from 1486), parish registers (from 1538), tithe rate and poor rate assessments (from 1592) and vestry minutes (from 1622). There is also the "Vellum Book", a book of record mainly of church property, dated 1466.[3][4]

St. Stephen's was one of two City churches dedicated to the Christian protomartyr St. Stephen who, by tradition, suffered lapidation (death by stoning) in Jerusalem in about 35 AD. Coleman Street is named after the charcoal burners who used to live there. From its situation in the quarter of London inhabited by many Jews, John Stow asserted, incorrectly, that the building had been used as a synagogue.[5]

Medieval church

The earliest surviving reference to the church is to "the parish of St. Stephen colemanstrate" during the reign of King John. At a date between 1292 and 1303 the advowson was acquired by Butley Priory in Suffolk, without licence: Butley challenged a royal appointment made c.1438, and its rights were acknowledged in 1449. The Dean and Chapter of St Paul's put in counter-claims, but the matter was resolved in Butley's favour in 1452.[6] In around 1400 the church is recorded as a chapel of ease to St. Olave Old Jewry. It regained parochial status in the middle of the 15th century.

In 1431, John Sokelyng, who owned a neighbouring brewery called 'La Cokke on the hoop', died and left a bequest to St. Stephen's on the condition that Mass be sung on the anniversary of his death and that of his two wives.[7] The gift was commemorated by a cock in a hoop motif that would decorate the church until 1940 and can still be seen in parish boundary markers.

Seventeenth century

Early in the 17th century, St. Stephen's became a Puritan stronghold.[8][9][10] A very prominent vestryman throughout this time was Sir Maurice Abbot.[11] The church was renovated at the cost of the parishioners in 1622, and a gallery was added over the south aisle in 1629.[12] John Davenport, the vicar appointed in 1624, later resigned to become a Nonconformist pastor. It was during his Puritan incumbency that the playwright and Shakespeare collaborator Anthony Munday was buried in the church in 1633. In that year Davenport departed for the United Netherlands, but returned in 1636 and, in company with Theophilus Eaton and a company centred upon a core of parishioners of St Stephen's, in 1637 sailed for New England. Finding Boston torn by religious dissent they diverted to Long Island Sound, where they founded the plantation of New Haven Colony, Connecticut.[13]

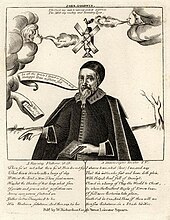

Davenport's successor, John Goodwin (instituted 1633), was also a prominent Puritan preacher.[14][15] Dame Margaret Wroth, a patron sympathetic to his views, who died in 1635 and was buried here beside her husband's parents, left benefactions for sermons to be preached on the anniversaries of her own burial and that of her daughter.[16] Goodwin was ejected from St Stephen's in 1645 for setting up a covenanted community within his parish and was briefly imprisoned after the Restoration for his political views. The five Members of Parliament impeached by Charles I repaired to Coleman Street in early 1642 when his troops were searching for them, and during the Commonwealth, communion was only allowed to those passed by a committee comprising the vicar and 13 parishioners – two of whom had signed the death warrant of Charles I.[17]

Rebuilding after the Great Fire

After its destruction in the Great Fire of London in 1666, the church was rebuilt on its old foundations.[18] Work on the exterior was completed in 1677. In 1691, further funds were provided from the coal tax to build a gallery and a burial vault. The total cost of restoration was £4,517.

The walls of the medieval tower quite substantially survived the Fire, and their old masonry remained visible on the north side in the later building, refaced with Portland Stone towards the top.[19] It stood at the north-west end corner, barely visible from the street.[20] It had a small leaded bell lantern, on top of which was a gilded vane in the form of a cock. The height of the tower to the top of the lantern was 85 feet (26 m).

Wren's church retained the plan of its medieval predecessor, which was in the form of an irregular quadrilateral that tapered towards the east. The walls were made from brick and rubble covered with stucco, only the south and east fronts being exposed. The main façade, at the east end, towards Coleman Street, was faced with Portland stone with rusticated corners, and had a circular pediment between two pineapples. Between the pediment and the large round-headed window below was a carving of a cock between two swags. The south front had five large round-headed windows.

The interior was a single space, undivided by piers or columns, with a flat ceiling,[12] coved at the sides, the coving pierced by round-headed windows.[21] The chancel was raised one step above the rest of the church.[12] The church measured about 75 feet (23 m) long and 35 feet (11 m) wide.[12] In 1676-77 the carver William Newman was employed to produce the altar-table and rails, and the altar-piece.[22] A detailed description of the interior furnishings exists.[23]

Until the early 19th century there was only one gallery, housing the organ at the west end.[24] Then however, despite the low interior – about 24 feet (7.3 m) high – further galleries, supported on iron columns, were added;[21] one in 1824, on the south side,[25] and two in 1827, one on the north side and another, for children above the organ gallery.[21][26] There was a small graveyard to the north of the church and a paved yard to the south. Over the gateway to the latter was a relief depicting the last judgement.[21]

It is possible that the explorer William Dampier was buried in the church or churchyard, as he was reported to have died in the parish in 1715.

An organ was provided by John Avery in 1775.

A notable vicar of St Stephen's was the Rev. Josiah Pratt (1768-1844), for 21 years Secretary of the Church Missionary Society.[27] His son John Henry Pratt was a noted clergyman-geologist.

Destruction

The church suffered slight damage from bombing in 1917. It was destroyed, along with all its fittings, by German bombing in the Blitz on 29 December 1940. The church was not rebuilt; instead its parish was combined with that of St Margaret Lothbury.

See also

- List of Christopher Wren churches in London

- List of churches rebuilt after the Great Fire but since demolished

References

- ^ "The City Churches" Tabor, M. p101:London; The Swarthmore Press Ltd; 1917

- ^ G. Cobb, The Old Churches of London (Batsford, London 1942).

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives, reference GB 0074 P69/STE1. Collection description at AIM25. "Vellum Book": MS 4456.

- ^ E. Freshfield, 'Some Remarks upon the Book of Records and History of the Parish of St. Stephen, Coleman Street', Archaeologia Vol. 50 (1887), pp. 17-57 (Internet Archive).

- ^ John Stow, A Svrvay of London (London 1603), p. 286 (Google).

- ^ J.N.L. Myres, W.D. Caröe and J.B. Ward Perkins, 'Butley Priory, Suffolk,' Archaeological Journal XC (1933), pp. 177–281, at p. 196 (archaeology data service pdf, p. 20).

- ^ Heulin, G. (1996). 'Vanished churches of the City of London. London: Guildhall Library Publications.

- ^ D.A. Kirby, The Radicals of St. Stephen's, Coleman Street, London, 1624-1642 (Corporation of London, 1970).

- ^ D.A. Williams, 'London Puritanism: the parish of St Stephen's, Coleman Street', The Church Quarterly Review vol 160 (1959), pp. 464-82.

- ^ A. Johns, 'Coleman Street', Huntington Library Quarterly, 71 part 1 (2008), pp. 33-54 (University of Chicago pdf).

- ^ A. Thrush, 'Abbot, Maurice (1565-1642), of Coleman Street, London', in A. Thrush and J.P. Ferris (eds), The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604-1629 (Cambridge University Press, 2010), History of Parliament Online.

- ^ a b c d Seymour, Robert (1733). A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, Borough of Southwark, and Parts Adjacent. Vol. 1. London: T. Read. p. 565.

- ^ I.M. Calder, 'Gift from St. Stephen's, Coleman Street, London', The Yale University Library Gazette Vol. 8, No. 4, Lafayette Centenary Number (April 1934), pp. 147-149 (Jstor - open).

- ^ E. More, 'John Goodwin and the origins of the New Arminians', Journal of British Studies Vol. 22 (1982), 50-70.

- ^ J. Coffey, John Goodwin and the Puritan Revolution: Religion and Intellectual Change in Seventeenth-Century England (Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2008), Google Preview.

- ^ 'Dame Margaret Wroth's Charity', Report from Commissioners: Charities in England and Wales (4) Session 21 April-23 November 1820, Vol. V (Commissioners, 1820) p. 148. Strype, Survey of London, Book 3 Chapter 4, p. 62, bungles both the date and the daughter's name.

- ^ Freshfield, 'Some Remarks upon the Book of Records',pp. 22-32 (Internet Archive).

- ^ P. Jeffery, The City Churches of Sir Christopher Wren (Hambledon Press, London 1996).

- ^ E.P. Loftus Brock, 'Notes on the Ancient Churches of London', Transactions of the St Paul's Ecclesiological Society, II (London, 1886-1890), pp. 12-18, at p. 15 (Internet Archive).

- ^ G. Cobb, London City Churches (B T Batsford, London 1977).

- ^ a b c d Godwin, George; John Britton (1839). "St Stephen's, Coleman Street". The Churches of London: A History and Description of the Ecclesiastical Edifices of the Metropolis. London: C. Tilt.

- ^ A.T. Bolton and H.D. Hendry (eds), The Parochial Churches of Sir Christopher Wren, Wren Society X Part 2 (Oxford University Press 1933), pp. 28, 31-32. Bolton and Hendry (eds), The City Churches, Vestry Minutes and Churchwardens' Accounts, Wren Society XIX (Oxford University Press 1942), p. 53.

- ^ 'Coleman Street Ward', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in London, Vol. 4: The City (Royal Commission, London 1929), pp. 71-76 (British History Online).

- ^ J.P. Malcolm, Londinium Redivivium, or, an Ancient History and Modern Description of London, Vol. IV (London 1807), p. 601.

- ^ Allen, Thomas; Wright, Thomas (1839). The History and Antiquities of London, Westminster, Southwark and Parts Adjacent. Vol. 3. London: George Virtue. p. 408.

- ^ George Godwin thought the galleries "give a mean appearance to the whole edifice"

- ^ J. Pratt and J.H. Pratt, Memoir of the Rev. Josiah Pratt, B.D., late Vicar of St. Stephen's, Coleman Street (Seeleys, London 1849) (Internet Archive).