Contents

Railroad land grants in the United States made in the 1850s to 1870s, were instrumental in the building the nation's railway network in the Central United States west of Chicago. They enabled the rapid settlement of new farm and ranch lands as well as mining centers. Overall, government land grants to Western US railroads during the 1850s to 1880s played a crucial role in shaping the economic, social, and geographic landscape of the United States, laying the foundation for much of the nation's modern transportation infrastructure and facilitating the westward expansion of settlement and industry.

History

The federal government operated a land grant system between 1850 and 1871, through which new railway companies in the west were given millions of acres they could sell to prospective farmers or pledge to bondholders. A total of 129 million acres (520,000 km2) were granted to the railroads before the program ended, supplemented by a further 51 million acres (210,000 km2) granted by the states, and by various government subsidies.[1] This program enabled the opening of numerous western lines, especially the Union Pacific-Central Pacific with fast service from San Francisco to Omaha and east to Chicago. West of Chicago, many cities grew up as rail centers, with repair shops and a base of technically literate workers.[2]

The Illinois Central Railroad in 1851 was the first railroad to receive a federal land grant. The grant was part of the Land Grant Act of 1850, which provided 3.75 million acres of land to support railroad projects. The Illinois Central received nearly 2.6 million acres of land in Illinois.[3]

The main laws, known as the Pacific Railroad Acts, were passed in 1862.[4] The highest priority at the time was to open speedy communications with the new state of California, to avoid going on foot or by a sea voyage that took six months.

The main factor, Republicans argued, was the immediate military emergency.[5] The Civil War was underway and was not going well for the Union; no one knew how many years it would last or which side would win. Furthermore there was a serious risk that Britain and France might enter in support of the Confederacy--there was a war scare with Britain in late 1861, and France was now favoring the Confederacy.[6] A war would cut off the ocean route to California (and its gold). The Confederate army was already marching toward California and there were fears that pro-Confederate political elements would take control of California, or it might split off as an independent country. A transcontinental railway thus was a military necessity.[7] The transcontinental link finally became operational in May 1869, four years after the Civil War ended.[8]n Nationwide, railroad mileage doubled from 35,085 miles in 1865 to 70,268 in 1873.[9]

Railroads for military, settlement, and economic needs

The government granted vast tracts of land to railroad companies as an incentive to build railways across the undeveloped western half of the country. They came during the Civil War of 1861–1865, when most of the cash budget was devoted to military expenses, and the gold mined in California was urgently needed. There was a military danger: in 1862 the Confederacy was attempting an invasion of California from Texas through New Mexico and Arizona. Furthermore, war with Britain and France was a serious possibility, which would cut off the oceanic connection to the West Coast. Financially, these land grants acted as a form of non-cash subsidy, making the construction of extremely expensive rail lines across a thousand miles of unsettled land financially feasible for private companies. Economically they would allow the creation of many thousands of new farms, ranches, mines and towns. [10]

The land grants were made in twenty- or fifty-mile strips, with alternate sections of public land given for each mile of track built. The federal government kept the in-between sections, which were open to homesteaders and land speculators. After the success of the Illinois Central grant of 1851, Congress extended the program in 1862-1872 to help new railroads that planned to link to California. It gave out 123 million acres. All together 1850 TO 1872 Washington gave 223 million acres, of which 35 million were forfeited. Washington also loaned cash for every mile built by these lines, at the rate of $16,000 for flatlands to $48,000 in the mountains. These loans were used to pay the construction crews, and were all fully paid back with interest by 1900. The largest grant went to the Northern Pacific, which obtained 40 milion acres (about the size of New England). [11]

After the policy of giving land grants was ended. one profitable transcontinental railroad was built in the 1880s and 1890s without subsidies, the Great Northern Railway. However, its system did absorb a small line that was given 3 million acres in 1857.[12]

Settlement of the Great Plains

The availability of railroad transportation made previously remote areas more accessible to settlers, encouraging westward migration and the establishment of new communities. This expansion of settlement helped to populate and develop the frontier regions of the United States.

In addition to buying from the railroads, prospective farmers could use the homestead law to obtain free land from the federal government. They had to file a claim and then work the land for five years. Or they could purchase from speculators who bought many homestead claims or bought land from the railroads. In general the railroads offered the best land with the best credit terms, but at slightly higher prices. Married couples planning a permanent family farm were usually the buyers. Single women were also eligible on their own for a free homestead from the government.[13]

In the Great Plains the population of the six states of the West North Central region ((Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota) soared from 988,000 in 1860 to 6,253,000 in 1890. The far West grew from 619,000 to 3,134,000.[14]

The amount of improved farmland in the West North Central states soared tenfold from 11.1 million acres in 1860 to 105.5 million acres in 1890.[15]

The land rush climaxed in the 1870s in Minnesota, Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas, as the population more than doubled from 1.0 million in 1870 to 2.4 million in 1880, while the number of farms tripled from 99,000 to 302,000, and the improved acreage quintupled from 5.0 million acres to 24.6 million.[16] Selling corn, wheat and cattle provided the cash for paying off the loans and taxes, and savings--the savings often went into speculative purchases of more farmland. For the family table, the housewife and the older daughters cultivated potatoes and vegetables, and cared for the chickens and the milch cow.[17][18][19]

Union Pacific Railroad

In addition to charges for freight and passenger service, the Union Pacific Railroad (UP) made its money from land sales to farmers and ranchers. The UP land grant gave it ownership of 12,800 acres per mile of finished track. The government kept every other section of land, so it also had 12,800 acres to sell or give away to speculators and homesteaders. The UP's goal in this regard was not to make a profit, but rather to build up a permanent clientele of farmers and townspeople who would form a solid basis for routine sales and purchases.[20]

Northern Pacific Railroad

The Northern Pacific Railway (NP) was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western states, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by Congress in 1864 and given nearly 40 million acres (62,000 sq mi; 160,000 km2) of land grants, which it used to raise money in Europe for construction. Construction began in 1870 and the main line opened all the way to the Pacific in September, 1883. The railroad had about 6,800 miles (10,900 km) of track and served a large area, including extensive trackage in the states of Idaho, Minnesota, Montana, North Dakota, Oregon, Washington, and Wisconsin. In addition, the NP had an international branch to Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. The main activities were shipping wheat, cattle, timber, and minerals; bringing in consumer goods, transporting passengers; and selling land.[21]

During the existence of the Dakota Territory (1861 to 1889, when it split into the states of North Dakota and South Dakota), the population first increased very slowly. Then it grew very rapidly with the "Dakota Boom" from 1870 to 1880.[22] The surge can largely be attributed to the growth of the Northern Pacific Railroad and its vigorous promotion in the U.S. and Europe. Settlers came from other western states as well as many from northern and western Europe. They sold their old farm and bought much larger farms on credit. They included large numbers of Norwegians, Germans, Swedes, and Canadians.[23][24] Cattle ranching on the vast open ranges became a major industry. With the advent of the railroad agriculture intensified: wheat became the main cash crop. Economic hardship hit in the 1880s due to lower wheat prices and a drought.[25]

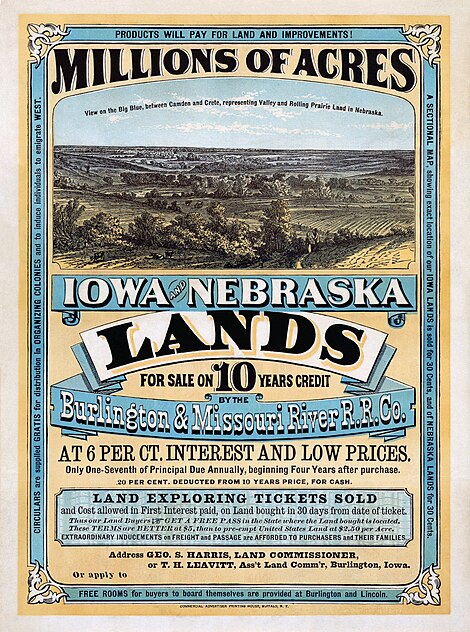

Migration from Europe

The railroads wanted experienced European farmers who could sell small farms in Germany or Scandinavia and use the gold to buy much larger farms. The railroads subsidizes travel for prospective buyers and their families and machinery. The sold farmland on good credit terms, such as 10% down and ten years to pay.[26] For example, the Union Pacific, the Burlington, Illinois Central, and the other western lines, opened sales offices in the East and in Europe, advertised heavily,[27] They offered attractive package rates for farmer to sell out and move his entire family, and his tools, to the new destination. In 1870 the UP offered rich Nebraska farmland at five dollars an acre, with one fourth down and the remainder in three annual installments.[28] It gave a 10 percent discount for cash.

A homestading farmer could get 160 acres free from the federal government after five years. However speculators controlled the best farmland and they charged more than the raillroads. Railroad sales were improved by offering large blocks to ethnic colonies of European immigrants. Germans and Scandinavians, for example, could sell out their small farms back home and buy much larger farms for the same money. European ethnics comprised half of the population of Nebraska in the late 19th century.[29]

Stimulus for economic growth

Railroads were crucial for connecting the resource-rich Western territories with Eastern markets. By providing land grants, the government facilitated the construction of railroads, which in turn spurred economic development in the West by making it easier to transport goods, people, and resources.[30]

The historians' debate about the wisdom of providing railroad land grants in the 1860s centered on the government's strategy, with discussions focusing on the potential benefits, drawbacks, and implications of this policy. At issue was the wisdom and fairness of giving land to railroads, as well as the resulting land speculation that made land more expensive for farmers. The government's intention was to promote railroad construction, which would in turn give military protection to the West Coast, facilitate cross-country movement of goods and passengers, stimulate population growth, and boost commerce, mining and industry. There were historical precedents on a small scale. However, the scale of land grants in the 19th century was much larger. [31]

Lloyd J. Mercer attempts by the use of econometrics to determine the values of railroad land grants of the 19th century to the railroads and to society as a whole. Mercer summarizes and criticizes previous treatments of this subject and then discusses his own findings. Using only data from the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific systems, Mercer concludes that the railroad owners received unaided rates of return which substantially exceeded the private rate of return on the average alternative project in the economy during the same period. Thus the projects turned out to be profitable although it was generally expected by contemporary observers that the roads would be privately unprofitable without the land grant aid. The land grants did not have a major effect, increasing the private rate of return only slightly. Nevertheless, it is contended that the policy of subsidizing those railroad systems was beneficial for society since the social rate of return from the project was substantial and exceeded the private rate by a significant margin.[32]

Integration of the nation

The new western railroads played a key role in uniting the country geographically and economically. The construction of transcontinental railroads, such as the Union Pacific and Central Pacific, facilitated travel and trade between the East and West coasts, reducing travel times and costs while promoting national cohesion.[33][34]

Cattle drives

Land grant railroads facilitated the integration of the Southwest into the national economy. After the Civil War the cattle industry expanded rapidly in Texas, but it lacked rail connections to the main packinghouses in Chicago. The solution of a cattle drive across unoccupied federal land north to the railheads in Kansas. Two railroads competed for the business, the Santa Fe and the Kansas Pacific. There were several well-travelled routes; the most popular was the Chisholm Trail with a destination in Abeline, Kansas. A typical drive would start with a herd of 2000 cattle (and a hundred or so horses), with a dozen cowboys, a cook and a trail master. They trekked about 15 miles a day, stopping at water holes and giving the cattle the chance to graze so they would not be losing weight. The cowboys made sure the cattle did not wander. There was no cost to use federal land, but when they went across Indian Territory (Oklahoma), they paid the Indians for their passage with some cattle.[35][36]

Finally after a month or two on the trail they reached a destination where the herd was sold to local dealers who shipped them east to packinghouses in Chicago. The cowboys were paid off when they reached their destination. Abilene and Dodge City were the most famous cattle towns, along with Newton, Caldwell and Wichita.[37] Theirreputation for violence was much exaggerated by Hollywood in films like "Twelve O'Clock High".[38]

The cattle drives flourished in the 1870s, and slowly moved west as the old paths were taken over by settlers. The cattle drives died out in the 1880s, as quarantines were imposed to stop the tick disease some herds carried. Furthermore cattle ranches in Kansas, Nebraska and the Dakotas grew rapidly in size, and produced better quality beef cattle which could be shipped east on the other land grant railroads.

See also

- Central Pacific Railroad

- Dakota Territory

- First transcontinental railroad

- History of Iowa#Transportation:Railroad Fever

- History of Kansas

- History of Nebraska#Land sales

- History of rail transportation in the United States

- Illinois Central Railroad

- Kansas Pacific Railway

- Northern Pacific Railway

- Pacific Railroad Acts

- Union Pacific Railroad

- Public Land Survey System

- see also Wikipedia articles on rail lines receiving land grants

Notes

- ^ Paul Gates, History of Public Land Law Development (1968, government document and not copyright) online; railroad land grants on pp 341–386.

- ^ James R. Shortridge, Cities on the plains: The evolution of urban Kansas (UP of Kansas, 2004).

- ^ John F. Stover History of the Illinois Central Railroad (Macmillan, 1975), pp. 15–30 online.

- ^ Heather Cox Richardson, The greatest nation of the Earth: Republican economic policies during the Civil War (Harvard UP, 2009) pp.170–208.

- ^ Richardson, p. 178.

- ^ Stève Sainlaude, France and the American Civil War: A Diplomatic History (2019) p.160.

- ^ Brian Schoen, "Containing Empire," in Kristin Hoganson and Jay Sexton, eds. The Cambridge History of America and the World: Volume 2, 1820-1900 (2021) p. 363.

- ^ Walter R. Borneman, Iron Horses: America's Race to Bring the Railroads West (2010) pp. 31–44.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970 (1976) p.731.

- ^ Richard White, Railroaded: The transcontinentals and the making of modern America (WW Norton, 2011) pp.9–21.

- ^ Richard White A New History of the American West (1991) pp 140–141.

- ^ John B. Rae, "The Great Northern's land grant." Journal of Economic History 12.2 (1952): 140-145. online

- ^ Patterson-Black, Sheryll (1976). "Women homesteaders on the Great Plains frontier". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 1 (2): 67–88. doi:10.2307/3346070. JSTOR 3346070.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970 (1977) p.22–32.

- ^ David R. Meyer, "The national integration of regional economies: 1860–1920." in North America: The historical geography of a changing continent (1987): 321-345 at 327.

- ^ Gilbert Fite, The Farmers’ Frontier, 1865–1900 (1966) pp 53–54.

- ^ Fite, pp. 46–53.

- ^ Gilbert C. Fite, "Great Plains farming: A century of change and adjustment." Agricultural History 51.1 (1977): 244-256.

- ^ David J. Wishart, ed. Encyclopedia of the Great Plains(U of Nebraska Press, 2004) pp. 35–39, 56, 217–25, 807–808.

- ^ Maury Klein, Union Pacific: 1862-1893 (1987) pp. 324–328.

- ^ James Blaine Hedges, Henry Villard and the Railways of the Northwest (Yale UP, 1930) pp. 112-132. online

- ^ Howard R. Lamar, ed., The New Encyclopedia of the American West. (Yale UP, 1988) p. 282

- ^ John H. Hudson, “Migration to an American Frontier.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 66#2 (1976), pp. 242–65, at 243–244; online

- ^ James B. Hedges, "The Colonization Work of the Northern Pacific Railroad" Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1926) 13#3 pp. 311-342 online

- ^ Lamar, The New Encyclopedia of the American West, p.282

- ^ "Land Grants and the Decline of the Railroads" Nebraska Public Media (2024) online

- ^ Berens, Charlyne; Mitchell, Nancy (2009). "Parallel Tracks, Same Terminus: The Role of Nineteenth-Century Newspapers and Railroads in the Settlement of Nebraska". Great Plains Quarterly: 287–300.

- ^ Fite, Gilbert C. (1966). The Farmers' Frontier, 1865-1900. pp. 16–17, 31–33.

- ^ Luebke, Frederick C. (1977). "Ethnic group settlement on the Great Plains". Western Historical Quarterly. 8 (4): 405–430. doi:10.2307/967339. JSTOR 967339.

- ^ Brian Gurney, and Joshua P. Hill. "Leveraging Railroad Land Grants and the Benefits Accruing in The New Economic Landscape." Journal of Transportation Management 30.1 (2019): 5+ online

- ^ Heywood Fleisig, "The Union Pacific Railroad and the railroad land grant controversy" Explorations in Economic History (1975). 11 (2): 155–172.

- ^ Lloyd J. Mercer, "Land Grants to American Railroads: Social Cost or Social Benefit?" Business History Review 1969 43(2): 134-151. online

- ^ Sarah Gordon, How the Railroads Transformed American Life, 1829-1929 (1997) pp 347–349.

- ^ David R. Meyer, "The national integration of regional economies: 1860–1920." in North America: The historical geography of a changing continent (1987): 321-345.

- ^ Howard R. Lamar, ed., The Reader's Encyclopedia of the American West (Yale UP, 1977), pp. 172–185, 268–272. online.

- ^ Wayne Gard, The Chisholm Trail (1969) online,

- ^ Robert R. Dykstra, The Cattle Towns. A Social History of the Kansas Cattle Trading Centres (Knopf, 1968)online.

- ^ Dykstra, Robert. "The Last Days of 'Texan' Abilene: A Study in Community Conflict on the Farmer's Frontier." Agricultural History 34.3 (1960): 107-119 online.

Further reading

- Athearn, Robert G. Union Pacific Country (U of Nebraska Press, 1971) online.

- Cochran, Thomas C. "North American Railroads: Land Grants and Railroad Entrepreneurship" Journal of Economic History, Vol. 10, Supplement. (1950), pp. 53-67. online

- Cronon, William. Nature's Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (1991) on the economic hinterland based on railroads

- Daly, Aiden Thomas. "Homes for the Industrious in the Garden State of the West: The Illinois Central Railroad's Role in the Economic, Environmental, and Agricultural Development of Illinois, 1850–1861" (PhD dissertation, Iowa State University; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2022. 29261430).

- Dykstra, Robert R. The Cattle Towns. A Social History of the Kansas Cattle Trading Centres (Knopf, 1968)online.

- Fite, Gilbert C. The Farmers' Frontier, 1865-1900 (1966) online

- Gates, Paul. The Illinois Central Railroad and Its Colonization Work (1934) online

- Gates, Paul Wallace. “The Promotion of Agriculture by the Illinois Central Railroad, 1855-1870.” Agricultural History 5#2 (1931), pp. 57–76. online

- Greever, William S. "A Comparison of Railroad Land-Grant Policies." Agricultural History 25.2 (1951): 83–90. online

- Gurney, Brian, and Joshua P. Hill. "Leveraging Railroad Land Grants and the Benefits Accruing in The New Economic Landscape." Journal of Transportation Management 30.1 (2019): 5+ online

- Hannah, Matthew G. Governmentality and the mastery of territory in nineteenth-century America(Cambridge UP, 2000).

- Hedges, James B. "The Colonization Work of the Northern Pacific Railroad," Mississippi Valley Historical Review 113#3 (1926), pp. 311–342 online

- Hill, Howard Copeland. "The Development of Chicago as a Center of the Meat Packing Industry" Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1923) 10#2 pp. 253–273. online

- Hughes, Jonathan. American Economic History (3rd ed. 1990; see ch. 14 on "Railroads and Economic Development" pp. 266–284 for review of the historiography.

- Lamar, Howard R. ed., The Reader's Encyclopedia of the American West (Yale UP, 1977) online.

- Overton, Richard C. Burlington Route, a History of the Burlington Lines (Knopf, 1965). online

- Petrowski, William R. The Kansas Pacific: a study in railroad promotion (Arno Press, 1981).

- Rae, John B. "Commissioner Sparks and the Railroad Land Grants." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 25.2 (1938): 211–230. online

- Richardson, Heather Cox. The greatest nation of the Earth: Republican economic policies during the Civil War (Harvard UP, 2009) pp.170–208, detailed history of passage of the Pacific Railroad Acts.

- Riegel, Robert Edgar. The Story of the Western Railroads (1926) online

- Shortridge, James R. Cities on the plains: The evolution of urban Kansas (UP of Kansas, 2004).

- Stover, John. History of the Illinois Central Railroad (1975) online

- Stover, John. Iron Road to the West: American Railroads in the 1850s (1978) online

- Stover, John. The Routledge historical atlas of the American railroads (1999) online

Financial and legal history

- Allen, Douglas W. "Establishing economic property rights by giving away an empire." The Journal of Law and Economics 62.2 (2019): 251-280.

- Ellis, David Maldwyn. "The Forfeiture of Railroad Land Grants, 1867-1894." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 33.1 (1946): 27–60. online

- Engerman, Stanley L. "Some economic issues relating to railroad subsidies and the evaluation of land grants." Journal of Economic History 32.2 (1972): 443–463.

- Fleisig, Heywood. "The Union Pacific Railroad and the railroad land grant controversy". Explorations in Economic History (1975). 11 (2): 155–172. doi:10.1016/0014-4983(73)90004-1.

- Fogel, Robert William. The Union Pacific Railroad: A case in premature enterprise (1906), econometrics

- Gates, Paul. History of Public Land Law Development (1968, government document and not copyright) railroad land grants on pp 341–386. online

- Henry, Robert S. "The railroad land grant legend in American history texts." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 32.2 (1945): 171–194. favorable to railways online

- Kammer, Sean M. "Railroad land grants in an incongruous legal system: Corporate subsidies, bureaucratic governance, and legal conflict in the United States, 1850–1903." Law and History Review 35.2 (2017): 391–432.

- Kammer, Sean M. "Land and law in the age of enterprise: A legal history of railroad land grants in the Pacific Northwest, 1864-1916" (PhD dissertation, U of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2015). online

- Mercer, Lloyd J. Railroads and land grant policy: a study in government intervention (1982) online

- Mercer, Lloyd J. "Rates of return for land-grant railroads: The central pacific system." Journal of Economic History 30.3 (1970): 602–626. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700086241

- Swenson, Robert W. "Railroad Land Grants: A Chapter in Public Land Law." Utah Law Review (1956): 456+.

External links

- Railroad History Bibliography by Richard J. Jensen, Montana State University