Contents

The assassination of Jean Jaurès, French deputy for Tarn and Socialist politician, took place on Friday, July 31, 1914, at 9:40 pm, as he dined at the Café du Croissant on rue Montmartre in Paris's 2nd arrondissement, in the heart of the Republic of the Croissant, not far from the headquarters of his newspaper, L'Humanité. He was hit by two gunshots: one bullet pierced his skull and the other nestled in woodwork. The famous politician collapsed, mortally wounded.

Committed three days before France's entry into World War I, this murder put an end to the desperate efforts Jaurès had made since the Sarajevo bombing to prevent a military explosion in Europe. It precipitated the rallying of the majority of the French left to the Sacred Union, including many socialists and trade unionists who had previously refused to support the war. The Sacred Union ceased to exist in 1919 when his assassin, Raoul Villain, was acquitted. The transfer of Jaurès's ashes to the Panthéon in 1924 underlined another political split within the Left, between communists and socialists.

Context

After the attack on Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, the European states were gradually drawn into a new international crisis by the play of alliances, leading to the outbreak of World War I within a month. Throughout these four weeks, Jaurès, the most prominent opponent of the war, felt the tension rising inexorably, and tried until his death to oppose it.

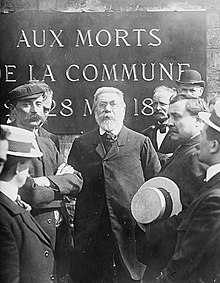

At the age of fifty-four, Jean Jaurès was the leading figure in the French socialist movement, the SFIO (French Section of the Workers' International), and a celebrated figure in international socialism, particularly since the death in 1913 of August Bebel, the leader of German social democracy. Jaurès, who entered politics in 1885 as a Republican deputy, an admirer of Gambetta, and a supporter of the Jules Ferry government, was very attached to the defense of the fatherland, as he explained in his book L'Armée nouvelle, published in 1911, criticizing Marx's famous phrase: "proletarians have no fatherland".[1] He was convinced, however, that wars were caused by the clash of capitalist interests, and that it was the duty of the working class to oppose them.[2]

Along with the Socialist group, he supported the Viviani government, which he felt was genuinely hostile to the war. On July 14, at the SFIO's extraordinary congress, which met until the 19th, he expressed confidence in the will of the working class and its representatives in the main countries to oppose the conflict, including through the weapon of the general strike. He supported the Keir-Hardie-Vaillant motion, the names of a British and a French socialist, which called for a strike in the event of imminent conflict: "rather insurrection than war", to which Jaurès added that the strike should be "simultaneously and internationally organized".[3] This earned him an attack from a newspaper like Le Temps, which on July 18 accused him of supporting the "abominable thesis that would lead to disarming the nation at a time when it was in peril", to which he replied in L'Humanité that "the strike would also paralyze the aggressor".[4]

He learned with concern of the growing number of commitments made as part of the Franco-Russian Alliance to be celebrated in St Petersburg by President Poincaré and Prime Minister Viviani between July 20 and 23. For months, Jaurès' entire strategy had been to condemn the alliance with despotic Russia and to seek mediation and rapprochement with England – in vain. When he was informed of the breakdown of diplomatic relations between Austria and Serbia on July 24, he realized the seriousness of the threat. On July 25, he came to support Marius Moutet, the Socialist candidate in a by-election in Vaise, a suburb of Lyon, and gave a speech denouncing the "massacres to come".[5] As he confessed to Joseph Paul-Boncour, Viviani's chief of staff, he was overcome by pessimism when he expressed himself fatalistically:

Ah, do you think you'll do everything to prevent this slaughter?... Besides, we'll be killed first, and we may regret it later.[5]

Believing he could still put pressure on the government, he maintained a certain reserve with regard to the demonstration organized by the CGT in Paris on July 27. The Socialist Party executive, which met on July 28 at the instigation of Jaurès, again expressed its support to the government.

Hoping that Paris and Berlin would be able to retain their mutual alliances, he attended the emergency meeting of the International Socialist Bureau of the Second International, which met in Brussels on July 29 and 30, at the request of the French Socialists. The aim was to urge the German and French leaders to take action against their allies. The board decided to convene the congress of the Socialist International on August 9 in Paris, instead of August 23 in Vienna. In a somewhat surreal atmosphere, most of the delegates, including Hugo Haase, co-chairman of the German SPD, expressed confidence in the ability of the people to avoid war. On the evening of the 29th, at the Cirque Royal, Jaurès and Rosa Luxemburg were acclaimed at a massive anti-war rally. The International Socialist Bureau voted unanimously to call for more anti-war demonstrations.[6]

Jaurès wanted to use the power of trade union and political forces, but without paralyzing government action. To this end, on July 30 he persuaded Léon Jouhaux to postpone the day of demonstrations planned by the CGT on August 2 until the 9th.[7]

The greatest danger at the moment is not, if I may say so, in the events themselves [...]. [...] It lies in the growing restlessness, in the spreading anxiety, in the sudden impulses born of fear, acute uncertainty and prolonged anxiety. [...] What matters above all is continuity of action, the perpetual awakening of working-class thought and consciousness. That is the real safeguard. That is the guarantee of the future.

— Jean Jaurès – Extracts from his last article in L'Humanité, July 31, 1914[8]

Friday, July 31, 1914, 9:40 pm: the assassination

When he returned to Paris on the afternoon of July 30, he found out that Russia was mobilizing. At the head of a socialist delegation, he obtained an audience with Viviani at around 8 pm, who revealed to him the state of preparation of the troops on the borders. Jaurès implored him to avoid any incidents with Germany.[9] Viviani replied that he had ordered French troops to retreat ten kilometers from the border to avoid any risk of incident with Germany.

On the morning of July 31, the Parisian press was unanimous in seeing Europe "on the brink of collapse". After consulting with friends and family such as Charles Rappoport and Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, Jaurès went to the Chamber of Deputies, where he was informed of the Austrian mobilization and the declaration of a state of threat of war (Kriegsgefahrzustand) in Germany.

He decided to meet again with the President of the Council, who was also Minister of Foreign Affairs, but saw only the Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Abel Ferry, nephew of Jules Ferry. At the same time, Viviani was unavailable, as he was receiving the German ambassador, Count von Schoen, who had come to convey his government's ultimatum to France: to say by 1 p.m. on August 1 whether it was in solidarity with Russia. He realized that conflict could no longer be avoided. At the same time, prefects warned all French mayors to have horses and carriages ready for requisition orders. According to Pierre Renaudel, who witnessed his meeting with Abel Ferry, Jaurès declared that if the government persisted in going to war "(he) would denounce the crazy-headed ministers". Abel Ferry, in a distressed – and by no means threatening – tone, simply replied, "But my poor Jaurès, we'll kill you at the first street corner! ... ". Abel Ferry was killed at the front, mortally wounded by shrapnel in 1918.

At the end of the day, he went to his newspaper's headquarters to prepare an anti-war mobilization article for the August 1 issue. Beforehand, he went out to dinner at the Café du Croissant on rue Montmartre, with his newspaper colleagues, including Pierre Renaudel, Jean Longuet, Philippe Landrieu, Ernest Poisson and Georges Weill. He sat with his back to the open window, separated from the street by a simple screen. Observing from the street the café room where he had spotted Jaurès dining, hidden by the curtain, the assassin fired two shots: the first penetrated the parietal region of the head, the second lost itself in the woodwork surrounding a mirror.[10] Jaurès was almost killed instantly by a cerebral haemorrhage.[11] In the confusion, Madame Poisson, wife of L'Humanité contributor Ernest Poisson, shouted: "Jaurès is dead! She was later credited with the exclamation "Ils ont tué Jaurès!" (They've killed Jaurès!), echoed by the workers, who lamented, ""They've killed Jaurès. It's war!" It is this apocryphal version blaming the nationalists that has survived.[12]

The murderer was Raoul Villain, a 29-year-old from Rémois, an archaeology student at the École du Louvre, and above all a member of the Ligue des jeunes amis de l'Alsace-Lorraine, a nationalist, pro-war student group close to Action Française.[13] He was arrested and declared that he had acted alone to "suppress an enemy of his country". This theory of an isolated act was repeated unchanged in the indictment drawn up on October 22, 1915.[13] He is described as an unassuming, calm and pious character, blond-haired, blue-eyed and youthful in appearance. Without ever having seen Jaurès, he gradually took it into his head to kill the traitor, the German.[14] Doubtless convinced of the necessity of his action since the previous December, he matured his deed throughout July, bought a Smith & Wesson revolver, practiced shooting, wrote a few incoherent letters, located the socialist leader's home, his newspaper, the café where he was a regular.[14]

For many months, even years, the nationalist press and representatives of the "patriotic" Leagues (such as Léon Daudet and Charles Maurras) had been raging against Jaurès' pacifist declarations and his internationalism, and singling him out as the man to be shot, because of his past commitment to Alfred Dreyfus. Statements of this kind abounded in the preceding weeks.[13]

Tell me, on the eve of war, do you think that the general who ordered [...] citizen Jaurès to be pinned to the wall and shot point-blank with the lead missing from his brain would not have done his most elementary duty?

— Maurice de Waleffe in L'Écho de Paris of July 17, 1914.

But the outrageousness of the written word merely concealed the gradual rise of nationalism in public opinion, which Jaurès and the Socialists seemed unwilling to recognize. Since the crises in Morocco and the Balkans in recent years, confrontation with Germany had become inevitable, as Clemenceau sensed. In the winter of 1913 and spring of 1914, the two men clashed fiercely over his hostile stance against the three-year military service law. In May 1912, Council President Poincaré's decision to declare Joan of Arc's feast day a national holiday was symbolic. Similarly, the rallying of many radicals to the Republicans and representatives of right-wing parties to elect Poincaré as President of the Republic in January 1913 also testified to the political shift underway.[15]

In his 1968 book Ils ont tué Jaurès (They killed Jaurès), François Fontvieille-Alquier notes the troubling relationship between Raoul Villain and the Imperial Russian ambassador Izvolsky. On several occasions, people close to Jaurès accused the Russian services of colluding with Raoul Villain, who may have been manipulated. In fact, Izvolsky generously showered the nationalist and warmongering press with money, prompting Jaurès to describe its financing as being in the pay of "that scoundrel Izvolsky".[16] However, the reality of Villain's manipulation has never been formally proven.[16]

Political consequences

Reactions

While the assassinated leader's relatives and socialist activists in Paris and Carmaux were shocked ("They've killed Jaurès"), and some right-wing extremists rejoiced loudly, all historical research shows that the population generally reacted with sadness to an event that symbolized the tipping point into uncertainty and fear of the horrors of the now inevitable war.[17]

The government, which met during the night, initially feared violent reactions in the major cities, and detained two cuirassier regiments in the capital, awaiting their departure for the border.[8] However, the reports received by Interior Minister Louis Malvy soon led him to believe that the left-wing organizations would not trigger any unrest. At the same time, the leadership of the Socialist Party announced that it would not be calling for demonstrations.

The assassination of Mr. Jaurès caused only a relative stir. Workers, shopkeepers and the bourgeoisie are painfully surprised, but are much more interested in the current state of Europe. They seem to see Jaurès's death as linked to much more dramatic current events.

— Xavier Guichard], director of the Paris municipal police, report sent on August 1, 1914 at 10:25 to the Ministry of the Interior.[18]

On the morning of Saturday August 1, President Poincaré sent a message of condolence to Madame Jaurès, and the government put up a poster condemning the assassination, in which the President of the Council, recalling the memory of the late leader, paid tribute, on behalf of the government, to "the socialist republican who had fought for such noble causes and who, in these difficult days, in the interests of peace, supported the patriotic action of the government with his authority".[18]

On August 1, at 2:25 pm, so as not to prevent workers from rallying to the war by decapitating the unions, and reassured by the reaction of the CGT's national bodies, Interior Minister Louis Malvy decided, in a telegram addressed to all prefects, not to use the notorious Carnet B, kept by the gendarmerie in each département, listing anarchist, syndicalist or revolutionary leaders who were to be arrested in the event of conflict, having expressed the intention of hindering the war effort.

At 4.25 pm, a handwritten yellow poster was posted at the Prefecture de Police, post offices and public monuments. In the hours that followed, white posters calling for mobilization with tricolored flags were affixed to the walls of every town hall in France.

On Sunday August 2, as Jean-Jacques Becker, who has compiled a wide range of sources, puts it, the French were "almost equidistant from consternation and enthusiasm, combining resignation and a sense of duty".[8]

On August 3, Germany declared war on France; the following day, England declared war in its turn.

Sacred Union

From August 1 onwards, there were many signs that the French left was rallying behind the war. Even some of the most die-hard anti-militarists switched over. Gustave Hervé's newspaper La Guerre Sociale published a special edition with three headlines: Défense nationale d'abord, Ils ont assassiné Jaurès, Nous n'assassinerons pas la France ("National defense comes first, they assassinated Jaurès, we won't assassinate France"). Le Bonnet rouge, Almereyda's anarchist newspaper, titled: Jaurès est mort ! Vive la France ("Jaurès is dead! Long live France"). La Bataille syndicaliste, a CGT organ, adopted the same tone.[8] At the Salle Wagram on August 2, at the Socialist Party meeting convened by Jaurès, Édouard Vaillant, the Commune's old revolutionary, declared: "In the face of aggression, socialists will do their duty. For the Fatherland, for the Republic, for Internationality".[19]

On the morning of August 4, Jaurès was officially buried. A catafalque was erected on the corner of Avenue Henri-Martin. Present in front of a huge crowd were all the authorities of the Republic, including the President of the Council, Viviani, the President of the Chamber of Deputies, Paul Deschanel, most of the ministers, leaders of the entire socialist and trade union left, and even the nationalist opposition, led by Maurice Barrès. It was the first demonstration of the national union. Léon Jouhaux, General Secretary of the CGT, made the most impressive speech, calling for arms. He shouted his hatred of war, imperialism and militarism.

Jaurès was our comfort in our passionate action for peace; it is not his fault that peace did not triumph. [...It's the fault of the emperors of Germany and Austria-Hungary...]. We pledge to sound the death knell of your reigns. I make this pledge in the name of the workers who have left, and those who will leave, before we head for the great slaughter.

On the same day, the President's desire for "union" was reported to both chambers by Council President René Viviani: "In the war that is beginning, France [...] will be heroically defended by all her sons, nothing of whom will break the Sacred Union before the enemy". At the Palais Bourbon, the Socialists voted unanimously for military credits.[20]

After the funeral ceremony, Jean Jaurès's body was taken by train to Albi,[21] where he was buried two days later in the Planques cemetery.[22]

On August 26, Viviani formed a government of national unity. Socialists, including the old revolutionary leader Jules Guesde, Minister of State, and Jaurès' close associates such as Marcel Sembat, Minister of Public Works, took part. In a manifesto dated August 29, the leadership of the SFIO Socialist Party asserted that "since it is not a question of ordinary participation in a bourgeois government [...but] of the future of the Nation, the party has not hesitated".[23] Only a small minority, including socialist Charles Rappoport and trade unionist Pierre Monatte, rejected the war and the union sacrée. The majority of German socialists also rallied to the sacred union. In December 1914, the only German MP to oppose the vote on war credits was Karl Liebknecht, who with Rosa Luxemburg helped found the Spartacus League of anti-war socialists.

Raoul Villain trial

Raoul Villain was incarcerated awaiting trial throughout World War I. After fifty-six months of pre-trial detention, when the war was over, his trial was organized before the Seine Cour d'assises. Villain was lucky enough not to be tried until 1919, at his request,[24] in a climate of ardent patriotism. At the hearings from March 24 to 29, his lawyers, including the great criminal lawyer Henri Géraud, argued that he was insane. They also argued that he was a lone man, as evidenced by his interrogation by Célestin Hennion, the Paris Prefect of Police, on the night of July 31, 1914.[25] Among the witnesses on his behalf was Marc Sangnier, who came to defend the "moral value" of a former disciple.[26] Raoul Villain was acquitted on March 29, 1919 by eleven votes out of twelve, one juror even finding that he had done his country a service: "If the war's adversary, Jaurès, had prevailed, France would not have been able to win the war. Jaurès's widow was ordered to pay the costs of the trial.[27]

On March 14, 1919, a fortnight earlier, the 3rd Paris Council of War, a military court, sentenced Émile Cottin, the anarchist who had shot Clemenceau several times on February 19, to death.[28]

In reaction, Anatole France wrote: "Workers, Jaurès lived for you, he died for you. A monstrous verdict proclaims that his assassination is not a crime. This verdict outlaws you and all those who defend your cause. Workers, watch out!".[29] On April 6, Paris socialist and trade union sections organized a demonstration to protest the verdict and honor Jaurès the pacifist. 100,000 people marched, and clashes with the police resulted in two deaths.[30]

Death of the assassin

Raoul Villain went into exile on the island of Ibiza. Shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936, the island fell into francoists hands, only to be recaptured by the Republicans, who soon left. Anarchist groups then took over, but the island was bombed by Franco's air force, and in the chaos of September 13, 1936, the anarchists executed Villain for spying for Franco's army, although it was not known whether they knew who he was.[31]

Jean Jaurès' remains are transferred to the Panthéon

Jaurès' official funeral, held on August 4, 1914, the first day of the war, was a sober affair. The 1919 verdict had shocked the left. Between 1921 and 1924, more than seven statues in tribute to Jaurès were inaugurated in various French towns. On June 3, 1923, at the inauguration of the Carmaux statue by his friend Anatole France, Édouard Herriot, leader of the Radical Party, suggested to the government that Jaurès' remains be transferred to the Panthéon.[32]

In 1924, Herriot became President of the Council of the Cartel of Leftists government, supported by the socialist SFIO party on the basis of a pacifist, anticlerical and social program against the policies of the National Bloc. Herriot saw the opportunity to give himself a symbolic foothold, while paying tribute to the man who had tried to prevent the war.[33] Édouard Herriot, Paul Painlevé, as well as Léon Blum and Albert Thomas, supporters of this government, had begun their political careers during the Dreyfus affair, and these Dreyfusards had been strongly influenced by Jaurès. The bill was passed by the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies on July 31, 1924, the tenth anniversary of Jaurès's assassination, despite opposition from a section of the Right, and also from the Communists, who protested against the confiscation of Jaurès by the "Cartel of Death".

The ceremony, initially set for September 4 or September 22, the anniversaries of the creation of the Third and First Republics respectively, was finally decided for Sunday November 23, 1924. Léon Blum wanted a majestic ceremony, while a number of enthusiastic Socialists favored a particular emphasis, and the Radicals did not want to overdo it. The ceremonial was finally entrusted to Firmin Gémier, founder of the Théâtre National Populaire in 1920, who entrusted the execution to musician Gustave Charpentier and poet Saint-Georges de Bouhelier.

The day before the ceremony, the coffin was taken from Albi by train to the Gare d'Orsay, accompanied by miners from Carmaux. It was then taken to the Salle Casimir-Perier at the Palais Bourbon. In addition to family and friends, the wake was attended by officials: Édouard Herriot and his ministers, cartel deputies and senators, and delegations from the CGT and the Human Rights League.

On Sunday November 23, 1924, his remains were taken to the Panthéon, in an official procession attended by all left-wing political movements except the Communist party.

The official procession, preceded by the red banners of the socialist sections, was opened by delegations from party organizations mingling with the constituted bodies. The Carmaux miners followed. Jaurès's coffin, perched atop a spectacular hearse, was carried to the Panthéon via the boulevards Saint-Germain and Saint-Michel. Newspapers reported a crowd of 80,000 to 100,000.[34]

Herriot delivered a speech in the nave of the Panthéon to an audience of 2,000, followed by the reading of a poem by Victor Hugo. The ceremony ended with an oratorio sung by a 600-strong choir.

The Communists had wanted to pay tribute to Jaurès by organizing a separate delegation. Following the first procession, they followed the same route, singing L'Internationale. Carrying red flags and placards reading "War on war through proletarian revolution", "Let's institute the dictatorship of the proletariat" and "Against the fascist leagues, let's oppose the proletarian centuries", they chanted slogans such as "Long live the soviets", "Long live the dictatorship of the proletariat" and "Down with the bourgeois parliament!" The police prefecture counted 12,000 organized demonstrators, joined by tens of thousands of spectators.[35]

In the November 24 issue of L'Humanité, Paul Vaillant-Couturier wrote of the days of May 1871:

As you march past the Panthéon, salute, with the memory of Jaurès, one of the bloodiest battles of the Commune. The Versailles bourgeoisie is still in power. You can only drive it out with weapons in your hands.

To underline the fact that there was no (or no longer any) national consensus, Action Française organized a tribute on the same day to Marius Plateau, general secretary of the Camelots du Roi, assassinated in January 1923 by Germaine Berton, an anarchist militant who had justified her act by saying she had wanted to avenge Jaurès. Accompanied by representatives of the clergy, a crowd of leaders and militants made their way to the Vaugirard Cemetery to hear Léon Daudet celebrate their martyrdom.[36]

In literature

- In Roger Martin du Gard's fresco Les Thibault, the event is described as follows:

A brief clatter, the burst of a tire, interrupted him; followed, almost immediately, by a second bang and a crash of glass. A pane of glass on the far wall had shattered.

A second of stupor, then a deafening sound. The whole room stood up and turned to the shattered glass: "Someone shot through the glass! – "Who? – Where? – From the street!"

...

At that moment, Madame Albert, the manageress, ran past Jacques' table. She shouted, "Mr. Jaurès has been shot!— Roger Martin du Gard in L'été 1914, 7th volume of Thibault.

References

- ^ Mehring, Franz, Vie de Karl Marx (in French), 1984, p. 581.

- ^ Becker 2004, p. 98.

- ^ Lacouture 1977, p. 127.

- ^ Becker 2004, p. 99.

- ^ a b Vovelle 2004.

- ^ Nettl, J.P., La Vie et l’œuvre de Rosa Luxemburg (in French), Maspéro, 1972, p. 583.

- ^ Becker 2004, p. 104.

- ^ a b c d Rioux 2003.

- ^ Auclair 1959, p. 322.

- ^ Appriou, Daniel (2011). Le fin mot de l'histoire (in French). Place des Éditeurs. p. 57..

- ^ Poisson, Ernest, « L’assassinat de Jean Jaurès », in Bulletin de la Société des études Jauressiennes (in French), April 1964.

- ^ Lalouette 2014, p. 221.

- ^ a b c Broche, François, Jaurès, Paris 31 juillet 1914.

- ^ a b Auclair 1959, p. 312.

- ^ Dupeux, G., in L’Histoire de France, under the direction of Georges Duby, Larousse, 1970, p. 486.

- ^ a b Ferry 1920.

- ^ Becker 1977.

- ^ a b Rabaut 2005, p. 73.

- ^ Becker 1977, p. 108.

- ^ Lacouture 1977, p. 132.

- ^ "Les obsèques de Jaurès". Le Petit Parisien. Paris. 5 August 1914. p. 2. Retrieved 11 March 2020..

- ^ "Les obsèques de Jean Jaurès à Albi". L'Homme Libre. Paris. August 7, 1914. p. 2. Retrieved March 11, 2004..

- ^ Lacouture 1977, p. 133.

- ^ « Pourquoi Raoul Villain a-t-il été acquitté ? » in humanite.fr.

- ^ Source: Police Prefacture archives..

- ^ Lalouette 2014, p. 88.

- ^ "Raoul Villain". cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ Clemenceau got the President of the Republic to commute the sentence to ten years' imprisonment. In: Michel Winock, Clemenceau, p. 428.

- ^ L'Humanité, « 1914 : Jaurès est assassiné », by Michel Vovelle, historian, article published on April 24, 2004.

- ^ Ben-Amos 1990.

- ^ Rabaut 2005, p. 150.

- ^ Agulhon, Maurice, Jaurès et la classe ouvrière, Éditions ouvrières, pp. 169-182.

- ^ Ben-Amos 1990, p. 4.

- ^ Ben-Amos 1990, p. 13.

- ^ Ben-Amos 1990, p. 16.

- ^ Ben-Amos 1990, p. 9.

Bibliography

Sources used for the writing of this article:

- Accoce, Pierre (1999). Ces assassins qui ont voulu changer l'histoire (in French). Paris: Plon. ISBN 978-2-259-18987-3. BNF: 370787626..

- Auclair, Marcelle (1959). Jean Jaurès. Paris: Le Seuil.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques (2004). L'Année 14 (in French). Paris: Armand Colin. ISBN 978-2-200-26253-2. BNF: 39201543.

- Becker, Jean-Jacques (1977). 1914, comment les Français sont entrés dans la guerre: contribution à l'étude de l'opinion publique, printemps-été 1914. Paris: Presses de la Fondation nationale des sciences politiques. ISBN 978-2-7246-0397-2. BNF: 34612817..

- Becker, Jean-Jacques and Kriegel, Annie, 1914. La guerre et le mouvement ouvrier français, Paris, Armand Colin, coll. Kiosque, 1964.

- Ben-Amos, Avner (October 1990). "La panthéonisation de Jaurès". Terrain (15).

- Broche, François, Jaurès, July 31, 1914, Balland, Paris, 1978.

- Ferry, Abel (1920). La Guerre vue d'en bas et d'en haut. Paris. BNF: 32102408.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Fonvieille-Alquier, François, Ils ont tué Jaurès !, Robert Laffont, Paris, 1968.

- Henri Guillemin, L’arrière-pensée de Jaurès, Gallimard, Paris 1966.

- Annie Kriegel, « Jaurès en juillet 1914 », Le Mouvement social, No. 49, October–December 1964, pp. 63-77.

- Lacouture, Jean (1977). Léon Blum.

- Lalouette, Jacqueline (2014). Jean Jaurès: L'assassinat, la gloire, le souvenir (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-03661-4. BNF: 43810210.

- Rabaut, Jean (2005). 1914, Jaurès assassiné (in French). Bruxelles: Complexe. ISBN 978-2-8048-0051-2. BNF: 400120303.

- Rioux, Jean-Pierre (October 2003). "La dernière journée de paix". L'Histoire.

- Vovelle, Michel (April 24, 2004). "1914 : Jaurès est assassiné". L'Humanité (in French). Archived from the original on 31 August 2007.