Qizhuang (Chinese: 旗裝; pinyin: qízhuāng; lit. 'Banner dress'), also known as Manfu (Chinese: 滿服; pinyin: Mǎnfú; lit. 'Manchu clothes') and commonly referred as Manchu clothing in English, is the traditional clothing of the Manchu people. Qizhuang in the broad sense refers to the clothing system of the Manchu people, which includes their whole system of attire used for different occasions with varying degrees of formality.[1] The term qizhuang can also be used to refer to a type of informal dress worn by Manchu women known as chenyi, which is a one-piece long robe with no slits on either sides.[1][2] In the Manchu tradition, the outerwear of both men and women includes a full-length robe with a jacket or a vest while short coats and trousers are worn as inner garments.[3]

The Manchu people have a history of about 400 years; however, their ancestors have a history of 4000 years.[2] The development of qizhuang, including the precursor of the cheongsam, is closely related to the development and the changes of the Manchu Nationality (and their ancestors) throughout centuries, potentially including the Yilou people in the Warring States Period, the Sushen people in the Pre-Qin period, the Wuji people in the Wei and Jin period, the Mohe people from the Sui and Tang dynasties, and the Nuzhen (known as Jurchen) in the Liao, Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties.[2][4] The Qing dynasty was a period when the Manchu's clothing development stage reached maturity.[2] In the Qing dynasty, the clothing culture of the Manchu people contradicted and collided with the clothing culture of the Han Chinese due to their cultural differences and aesthetic concepts.[4] Some Qing dynasty court dress preserved features and characteristics which are distinct from the clothing worn by the Manchu prior to their conquest of the Ming dynasty.[5]: 42 The Qing dynasty officials also wore court dresses, which were variants of Manchu clothing at the court.[5]: 41

Characteristics and cultural significance

Characteristics

Manchu clothing contrasted to the Hanfu, Han Chinese clothing, worn in the Ming dynasty; "in contrast to the ample, flowing robes and slippers with upturned toes of the sedentary Ming, the Manchu wore the boots, trousers, and functional riding coats of nomadic horsemen".[5]: 39

Manchu of both sexes wore trousers to protect their legs from the horse's flanks and from the elements.[5]: 40 Their boots had rigid soles to facilitate archery on horseback by allowing the riders to stand in the iron stirrups.[5]: 40 The Manchu people also wore hoods which provided insulation and were essential to protect the wearer from the cold Northeast Asian winters.[5]: 39–40

Manchu coats (and robes) were typically closed fitting and had 4-slits opening on 4 sides (2 sides of the garment, back and front) to facilitate ease of movements when horseback riding;[5]: 40 [6] their sleeves were long and tight with their sleeves cuff ending in the shape of a horse's hoof, referred as matixiu (Chinese: 马蹄袖; pinyin: mǎtíxiù; lit. 'horse hoof cuff'), which was meant to protect its wearer's back of the hands from the wind.[5]: 40 [6][7] The Manchu's robes were overlapping in the form of a lute-shaped (or slant/curved) front, a Manchu innovation which was used, distinguished the Manchu robes from similar-looking clothing worn by the Mongol and by those worn by the Han Chinese.[7] Manchu robes were fastened with loop and toggle buttons at the centre front of the neck area, right of the clavicle, under the right arm and along the right seam; this ways of closing their clothing differed from the Han Chinese who fastened a knotted button at the right neck opening near the shoulder line.[7] Matixiu and slanted opening remained main features of Manchu dress until the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911.[7]

Their male traditional hairstyle is the queue, which is called bianzi in Chinese and soncoho in Manchu language.[8]: 59

Emphasis on Manchu cultural identity

The Manchu elites perceived themselves and the emperor as being Manchu first with a long tradition rooted in riding horses, shooting arrows, and hunting; they saw their clothing as having been designed to be suitable for their lifestyles and practices.[9]: 147 Their clothing was associated with martial vigour;[5]: 40 Manchu clothing allowed greater ease of movement while the Han Chinese wide and long-sleeved robes limited movements.[5]: 40

According to the Documents of History of Qing Dynasty by Yufu zhi: "Manchu people are good at riding and shooting. If we adopt Han people's clothes easily and gradually lose the skill of archery and horse riding and no longer worship martial arts, isn't that a pity that we will keep these weapons but have no reasons to practice them".[4]

The Manchu elites saw these characteristics of the Manchu culture as very important features which needed to be preserved, fully emphasized and expressed in their rule.[9]: 147 Therefore, in the early Qing dynasty, the Manchu rulers emphasized that the Han Chinese had to follow the dress code of the Manchu.[4]

However, not every Han Chinese were required to wear Manchu clothing under the Tifayifu policy due to another mitigation policy adopted by the Qing court typically referred as the "ten rules that must be obeyed and ten that need not be obeyed", advocated by Jin Zhijun.[4]

Ethnic markers between Manchu and Han Chinese women

Through a mitigation policy to the Tifayifu, Han Chinese women were allowed to keep the style and characteristics of the Ming dynasty's women clothing; allowing the coexistence of both Manchu and Han Chinese women's clothing.[4] Manchu and Han Chinese women differed from each other in their dress style.[6]

Han Chinese women followed the long tradition of liangjie chuanyi (Chinese: 两截穿衣; pinyin: liǎngjié chuānyī), which refers to the wearing of two-part top-bottom garment style, when wearing their hanfu. This tradition persisted throughout centuries up to the early 1920s.[1] Liangjie chuanyi-style clothing became one of the ethnic markers of the Han Chinese women's identity.[1]

On the other hand, Manchu women wore a one-piece long dress.[1][3] However, they borrowed some elements from each other in the Qing dynasty, for example, wide robe sleeves which are typical features in the Han Chinese women's clothing was adopted in the informal daily outfits of the Manchu women.[6] Manchu women's clothing was therefore influenced by the Han Chinese clothing culture.[4] Manchu women also had natural feet and did not engage in foot binding as opposed to the Han Chinese women.[8]: 59

Pre-Manchu history

Sushen/Yilou people

In the Shang and Zhou dynasties, the earliest ancestors of the Manchu were the Sushen people who lived in the Songhua river basin in China.[2] Their clothing culture was influenced by their productivity and geographical environment; the Sushen people lived on fishing and hunting; therefore, their clothing were made out of wild animal fur.[2] According to Guo Pu's commentary in Shanhaijing, the Sushen people resided north of the Liaodong Commandery lived in caves and only wore pig hides for clothing and in winter, they would smear grease on their bodies to protect themselves from the wind and cold.[10]: 191

According to the Book of Jin, the Sushen (also known as Yilou) lived north of the Changbai Mountain; a Sushen man would stick feathers in a woman's hair and if the woman accepted, he would propose her to be his wife and marry her in a formal and respectful way; a custom which was passed down to the Yuan and Ming dynasties.[11]: 42

Mohe people

In the 7th century Tang dynasty, the descendants of the ancient Sushen people were known as the Heishui Mohe (Chinese: 黑水靺鞨; pinyin: Hēishuǐ mòhé; Korean: 흑수말갈; Hanja: 黑水靺鞨; RR: Heuksu Malgal).[12] Another descendants branch of the Sushen, Yilou, and Wuji people were the Sumo Mohe who established the Bohai kingdom;[13]: 55 a kingdom which was made up of a large number of Mohe tribesmen in terms of population while the ruling class was composed mostly of Goguryeo people.[14]: 72, 89 [15]: 36 Some Mohe people however managed to become part of the ruling elite of Bohai.[14]: 89 [15]: 36 Bohai eventually fell under the Khitans in 926 and the Goguryeo elites of Bohai became refugees in Goryeo leaving the indigenous Mohe people behind, who then became the subjects of the Liao dynasty.[14]: 91

The Heishui Mohe had the customs of using wild boar tusks and pheasant tail feathers for their headdress.[11]: 42 According to the Old Book of Tang, the New Book of Tang, and the Book of Sui, Mohe men wore clothing of leather and decorated their hats with pheasant feathers.[16]: 138 The Mohe people, who lived in the northern regions and eastern regions of Bohai, lived through hunting and fishing and wore clothing made out of fur (including sable, bear, and tiger) to protect against the cold with fur attached to the clothing.[16]: 145–146

Jurchen/Nuzhen history

The ancestors of the Manchu, the Jurchen people[13]: 55 , also fully reflected the characteristics of the Manchu people as nomadic people; their clothing were zuoren (closing to the left) and their sleeves had horse-hoof cuff.[2] The Jurchen clothing also reflected some fusion of Han and Manchu culture.[2] Throughout the Jin, Liao and early Qing dynasties, the Jurchen retained their traditional customs of wearing feather caps and coats.[11]: 42 The young Jurchen girls would wear a tube-shaped, five-colour beads which were engraved with ornamental design made of bird-neck bone.[11]: 42

Five dynasties and ten Kingdoms, Liao dynasty, Song dynasty

During the Five dynasties period, the Mohe people started to be referred as the Jurchen people (Chinese: 女真; pinyin: Nǚzhēn),[17]: 338 they were referred as such by the Khitans who had founded the Liao dynasty.[18]: 85 The Liao dynasty had subdued the Heishui Mohe who lived along the Heilongjiang river, the Songhua River, and in the Changbai Mountains.[18]: 85 The Jurchens, therefore, emerged from the Mohe tribes who lived south and west of the Changbai mountains and north to the Bohai kingdom.[19]: 56

In the early history of the Jurchen, the Jurchen liked to wear white clothing and shaved the front of their head above the temples while the rest of their hair hung down to their shoulders.[17]: 40 They could also shave their hair at the back of the head and bundled it with coloured silk; they also wore golden locks as their ornaments.[17]: 40 The wealthy Jurchen used pearls and golds as ornaments.[17]: 40 Jurchen women braided their hair and wound them into a hair bun without wearing a hat.[17]: 40 The Jurchen wove hemp as they did not raise silkworms; they used the fineness of hemp cloth to indicate their wealth.[17]: 40 In winter, fur coats were used by both the rich and the poor to keep themselves warm.[17]: 40

Jin dynasty

The sheng (Chinese: 生; lit. 'raw') Jurchens lived a relatively primitive and indigenous lifestyle based on hunting and herding similar to the lifestyle of their ancestors.[19]: 56 The Jurchens founded the Jin dynasty in 1115 and eventually overthrew the Liao dynasty.[19]: 56 Some remnants of the Bohai people became the subjects of the Jin after it overthrew the Liao dynasty; and by the mid-Jin dynasty, the Bohai people lost their distinct identity with assimilation.[13]: 55 Soon after having founded the Jin dynasty, the Jurchen elites abandoned their sheng ways of life having been first influenced by Bohai and later on by gaining much of northern China and the former Song dynasty population which were large in numbers.[19]: 57 The Jurchens who lived in the Jin dynasty quickly adopted Han Chinese culture,[19]: 56, 68 and by the late 12th century, Hanfu had become the standard form of clothing throughout the Jin society, in particular by the elites.[19]: 61

After having conquered northern China, in 1126, a proclamation was issued by the Grand Marshal's office stipulating that the Jurchens had conquered all and it would be therefore appropriate to unify the customs of the conquered people to make them conform to the Jurchen norms; therefore the Chinese men living in the conquered territories were ordered to shave their hair on the front of their head and to dress only in Jurchen-style attire under the threat of execution to display their submission to the Jurchens.[20]: 228 [21] This shaving hair order and adopting Jurchen clothing was however cancelled just a few months after it was stipulated as it was too difficult to enforce.[21] In general, the Jin dynasty Jurchen clothing were similar to those worn by the Khitans in Liao, except for their preference for the colour white. Yuanlingpao with tight sleeves (closing to the left side, with pipa-shaped collar) were worn by men with leather boots and belts.[22]: 136 Jurchen women liked to wear jackets (either dark red or dark purple) which closed to the left side with long flapped skirts.[22]: 136–137 It is also recorded in the section Carriages and Costumes of the History of Jin Dynasty that Jurchen clothes were decorated with bears, deer, mountains and forest patterns.[22]: 136

In 1127, the Jin dynasty occupied the Northern Song capital and the territories of the Northern Song and the Han Chinese became the majority population of the Jin dynasty; the Han Chinese were allowed to practice their own culture.[19]: 68 The hair shaving and adopting Jurchen clothing imposition order on the Chinese was once again reinforced in 1129; however, it does not seem to have been strictly been enforced.[23]: 281

In the 1150, Emperor Hailing established a sinicization policy.[24]: 92 Under his reign, the Chinese in Honan were allowed to wear Chinese clothing.[23]: 281

In the late 1160s, Emperor Shizong, the successor of Emperor Hailing, attempted to revive old Jurchen culture[19]: 68 [24]: 92 and to preserve the Jurchen's cultural identity.[23]: 281 By his time, many Jurchens appeared to have adopted Chinese customs and had forgotten their own traditions.[23]: 281 As a result, Emperor Shizong also prohibited the Jurchens from adopting Han Chinese attire.[24]: 92 [23]: 281 Jurchen material culture dating about 1162 were found in the coffin of the Prince of Qi, Wanyan Yan, and his wife, where Wanyan Yan and his wife were dressed in layers of clothing in the duplicate style as those worn by Lady Wenji and the warriors who accompanied her in the painting Cai Wenji returning to Han.[19]: 61 The Prince of Qi wore earrings, drawers, padded leggings, jerkins, boots, a padded outer jacket with medallion designs at the back and front jacket; soft shoes and socks, and a small hat while his wife wore a short apron, trousers, leggings, a padded silk skirt, a robe with gold motifs, silk shoes with soft soles and turned-up toes.[19]: 62 These forms of Jurchen clothing were in the styles of the old Jurchen nobility; a style which may have been typical of the clothing of the Jin imperial elite at some point in the late 12th century during the reign of Emperor Shizong, who emphasized the values of the old sheng Jurchen and attempted to revive Jurchen culture and values.[19]: 57, 61–62 The tribeswomen in the painting Cai Wenji returning to Han wear Jurchen attires consisting of leggings, skirts, aprons made of animal hide, jackets, scarves, hats made of fur or cloth; Wenji also wears Jurchen-style attire consisting of an ochre yellow jacket, silver yunjian (a symbol of high rank), boots, and fur hat with ear flaps; the tribesmen wear typical sheng Jurchen clothing with the exception of a Han Chinese official.[19]: 58–59 However, clothes worn by the Prince of Qi and his wife were not rough-woven wool, felt, and animal-skin that the sheng Jurchen wore; instead, they wore clothing made of fine Chinese silks, with some decorated with gold thread; they also did not wear boots.[19]: 62

According to Fan Chengda who visited the Jin dynasty in 1170 following the Jin conquest of the Northern Song dynasty, he noted that the Han Chinese men had adopted Jurchen clothing while the women dressing style were still similar to the Hanfu worn in the Southern Song dynasty (although the style was outdated).[19]: 72

After the death of Emperor Shizong, the policy of Jurchenization was abandoned and sinicization returned quickly.[24]: 92 By 1191, the rulers of the Jin dynasty perceived their dynasties as being a legitimate Chinese dynasty which had preserved the traditions of the Tang and Northern Song dynasties.[24]: 92

By the 13th century, the Jurchens of Jin considered the sheng Jurchens as outsiders, barbarians, and sometimes even as their enemies.[19]: 56, 59–60

Manchu history

Ming dynasty and later Jin dynasty

Transition from Jurchen to Manchu

Manchu (and Jurchen) clothing initially looked similar to the clothing worn during the early dynasties of conquest in its core features.[5]: 39 The Jurchens and Manchu were originally hunters who made their clothing from the hides of animals they hunted.[25] They also relied on trade to obtain the cloth required to make their horse-riding clothing; their cloth coats would then often be quilted or face with fur to increase protection against the cold.[26] They wore surcoats, such as magua.[26] After 1630, their magua often reflected its wearer's association to his banner through the colour of the garment or its trimmings.[26]

Prior to the Ming dynasty conquest, the Manchu (and their predecessors[27]: 28 ) had already been bestowed with dragon robes by the Ming court as diplomatic gifts and bribes.[25][28]: 6 Thus, Manchu rulers ordered to that silk Ming dynasty dragon robes be trimmed with sable.[27]: 25 During the time of Nurharci, the highest-ranking members of the Jurchen elites wore Manchurian pearls, sable, and lynx: the highest members of the elites wore plaited sable jackets and robes of black sable, they wore Chinese-style racoon-dog or lynx fur robes; 2nd rank men wore robes or coats made of plain raccoon-dog lined with sable; and the men of the 3rd rank would wear dragon robes lined with sable in the Jurchen style.[27]: 28 Lower noblemen were dressed in squirrel and weasel fur.[27]: 28

The term "Manchu" was only adopted in 1635 by Hong Taiji[5]: 36 in an attempt to create a new identity and people who referred to them as Jurchen would be executed.[8]: 58–59 Hong Taiji had declared:[8]: 59

Originally, the name for our people [gunrun] was Manju, Hada, Ula, Yehe, and Hoifa. Ignorant people call these "Jurchens". But the Jurchens are those of the same clan of Coo Mergen Sibe. What relation are they to us? Henceforth, everyone shall call [us] by our people's original name, Manju. Uttering "Jurchen" will be a crime.

-

Illustration of a Jurchen of the 14th century.

-

A Jurchen man, Ming dynasty, 15th century.

-

Late Ming dynasty depiction of a Jurchen tribesman.

-

Painting of Nurharci, 17th century

Qing dynasty

First half of 16th century

The Manchu invaded the late Ming dynasty and overthrew the Ming dynasty to establish the Qing dynasty.[1] The Manchu, Mongol bannermen and Han bannermen in Later Jin (1616–1636) territories engaged in the practice of shaving their foreheads since 1616. When the Manchu arrived in Beijing, they passed the tifayifu policy which required Han Chinese adult men (with the exceptions of specific group of people who were part of a mitigation policy advocated by Jin Zhijun, a former minister of the Ming dynasty who had surrendered in the Qing dynasty[4][note 1]) to shave their hair (i.e. adopting the Manchu's queue as a mark of their submission to Qing dynasty rule[5]: 40–41 and dress in Manchu-style; the Han Chinese women were part of the exempted people and were therefore spared from the policy.[1][4] Women in the Qing dynasty dressed accordingly to their husband's ranks.[29] According to Chinese customs, Han Chinese men were supposed to comb their long hair and hide it under caps. The Qing imposed the shaved head hairstyle on men of all ethnicities under its rule even before 1644 like upon the Nanai people in the 1630s who had to shave their foreheads.[30][31] The men of certain ethnicities who came under Qing rule later like Salar people and Uyghur people already shaved all their heads bald so the shaving order was redundant.[32] However, the shaving policy was not enforced in the Tusi autonomous chiefdoms in Southwestern China where many minorities lived. There was one Han Chinese Tusi, the Chiefdom of Kokang populated by Han Kokang people. All members of the Eight Banners, regardless of their ethnic origins, were required to wear Manchu dress.[5]: 40 Banner women were not allowed to adopt Chinese customs such as foot binding, wear single earrings, and wear Ming-style clothing with wide sleeves.[5]: 41 Qing Manchu prince Dorgon initially canceled the order for all men in Ming territories south of the Great wall (post 1644 additions to the Qing) to shave. It was a Han official from Shandong, Sun Zhixie and Li Ruolin who voluntarily shaved their foreheads and demanded Qing Prince Dorgon impose the queue hairstyle on the entire population which led to the queue order.[33][34]

Following their conquest of the Ming dynasty, the Manchu continued the wearing the Ming-style dragons robes but altered them by adding fur at the collar and cuff and sable at the skirts.[27]: 25 In 1636, a proclamation was passed to guide the principles that the Manchu rulers had to avoid adopting the traditional clothing dress code of the Ming dynasty with the Manchu rulers reminding their people that adopting Han Chinese customs of the Ming dynasty would make their people become unfamiliar with shooting and horseback riding.[7] Hong Taiji who developed a dress code after 1636 stipulated that there was a direct connection between the adoption of Han Chinese's clothing, speech and sedentary lifestyle and the decline of the earlier Conquest dynasties (Liao, Jin, and Yuan).[5]: 40 Manchu rulers also firmly rejected the adoption of Ming dynasty's court clothing and led to the executions of people who suggest adopting the Ming dynasty court dress.[5]: 40 [35]: 60–61 [note 2]

In 1637, Hong Taijji reminded his people that the "wide robes with broad sleeves" of the Ming dynasty were completely unsuitable to the Manchu lifestyle and expressed his worries that his descendants would forget the source of their greatness (i.e. Manchu conquests were founded on their horseback riding and their archery skills) and adopt Han Chinese customs.[5]: 40 In the same year, Manchu noblemen and women were ordered by the early Qing court to wear freshwater Manchurian pearls in their headwear, including hats and hairpieces.[27]: 28

After 1644, new revisions were made on the clothing regulations: 1st rank princes had to wear 10 Manchurian pearls on their head; 8 pearls for the 2nd rank princes; 7 for the 3rd rank princes; the number of numbers were graded down until the lowest-ranking aristocrats who were only allow to wear one single pearl.[27]: 28–29

-

Daisan (1583-1648) wearing an altered Ming dynasty dragon robe (jifu), 17th century

-

Chaofu of Lin Yinzu, between 1629 and 1664

-

Jifu, Qing dynasty, 17th century

Second half of 17th century to late 18th century

In the early 1652, surcoats with insignia badges started to be worn to indicate the wearer's rank.[26] They were also wearing three-quarter length surcoats, called duanzhao, entirely lined with fur on cold weather days.[26] The duanzhao were considered luxurious, and they were eventually restricted to the members of the elites (nobles and officials of the top three ranks) and to the imperial guards; the type of fur and the lining colour was according to rank.[26]

During the Kangxi and Qianlong periods, the Manchu clothing system was continuously improved.[2] During the Qianlong reign, some banner women transgressed the ban of wearing Hanfu and Han Chinese jewelries (specifically earrings).[5]: 41 [note 4]. The Qianlong Emperor reiterated the warning of abandoning Manchu clothing to his descendants noting that every northern dynasties that had adopted Chinese robes had hats had died out within one generation after they had abandoned their native dress;[7] the Qianlong Emperor had cited Hong Taiji's earlier analogies.[5]: 40 The Manchu women's chanyi and chenyi (informal robes) both became popular in the reign of the Qianlong Emperor and were worn with a long neck ribbon called longhua.[29]

-

Man's jifu, first quarter of the 18th century

-

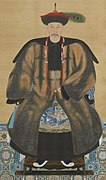

Portrait of Shang Zhixin, second half of 17th century.

-

Sunggan, late 1700s

-

Liang Chaogui, between 1788 and 1794

-

Prince Yinzhi, 3rd son of Kangxi Emperor

Standardization of Manchu imperial and court clothing in Qing dynasty

The Manchu rulers also established new dress code regulations codifying attire worn by the imperial family, the Qing dynasty court and their court officials to distinguish the members of the ruling elites from the general population.[29] The Board of Rites worked on the standardization of the Imperial clothing of the Qing dynasty. developing the sumptuary regulations throughout the 17th and early 18th centuries.[9]: 147 The Board of Rites worked on ways to create distinctions between the clothing worn by the Emperors from other members of the political circle by limiting what people could wear and not wear; they also developed the imperial clothing by drawing on both the Manchu's and Han people's traditions.[9]: 147

It is however only in the Qianlong period, that Imperial clothing became an amalgamation of Manchu-style tailoring with adopted Chinese designs.[9]: 147 The Qing Emperor would therefore be dressed in Chinese symbols and wear colours which reflect his rule as a Chinese emperor while at the same the tailoring of his robes would expressed his connection to the Manchu martial tradition of horse riding and archery.[9]: 147 The new dress code was found in the Huangchao liqi tushi (lit. 'Illustrations of Imperial Ritual Paraphernalia') commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor by the year 1759 as he was concerned that the customs of the Manchu people would be diluted by the Han Chinese ways.[25] The twelve ornaments were also reintroduced in 1759 and reappeared on the Qing dynasty court robes, first on the chaofu and later on the jifu.[25]

The Huangchao liqi tushi was therefore published and enforced by the year 1766; it contained a long section regulating the clothing worn by the emperors, princes, noblemen and their consorts, Manchu officials along with their wives and daughters, and also stipulated the dress code for Han Chinese men who became a mandarin and were serving the Manchu court, along with their wives and by the people who were waiting for an appointment.[25] The stipulated clothing was divided into official and unofficial clothing and was then subdivided into formal, semiformal and informal categories: formal official clothing and semiformal clothing were worn at the court; informal official clothing was worn when travelling on official business, when attending court entertainment and on important domestic occasions; non-official formal clothing was worn on family occasions.[25] Clothes were also regulated by the seasons.[25]

End of 18th century to first half of 19th century

In the Jiaqing and Daoguang period, Manchu clothing evolved and more decorations were used to adorn women's clothing.[2]

By the mid-19th century, the matixiu (Chinese: 马蹄袖; pinyin: mǎtíxiù; lit. 'horse hoof cuff') sleeve cuffs of Manchu women's robe became wider and the size of the cuff also became bigger, particularly on the formal festive coats worn by Manchu court women.[7]

Second half of 19th century

-

Wen-siang, between 1868 and 1870

-

Manchu lady, between 1871 and 1872.

-

1899

-

A Manchu woman's chenyi robe, 1875–99.

20th century

-

Manchu people, 1906

-

Mongol noble wore Qing-style clothing, 1910

Republic of China

By 1911, the topple of the last Qing dynasty Emperor Puyi by Sun Yat-sen and the demise of the Qing court led to the extinction of the Qing dynasty sartorial regulations.[37]: 34 When the Republic of China was established, men all over China cut their queues and wore Western-style clothing.[37]: 34 [38]: 343

The Northern Expedition entered Beijing in 1928 and held disdain towards the city; their soldiers treated people who worked in the old government as captives and wanted to "wipe out everything": they banned Manchu women's hairstyles and the wearing of magua; they also prohibited temple fairs to follow the Chinese calendar.[39]: 87

Types

According to the Manchu tradition, the outerwear of both men and women includes a full-length robe with a jacket or a vest while short coats and trousers are worn as inner garments.[3]

During the Qing dynasty, new types of clothing with elements and features which referred to the Manchu tradition also appeared, leading to changes in the cut of the formal and semi-formal attire worn by both the Manchu and the Han Chinese; for example, the Manchu robes closed to the right side of their body, 4-slits at the bottom of their garments (while the Han Chinese only wore two) which facilitated horse riding, the shape of the sleeves were changed from long and wide to narrow.[6] Some sleeves had matixiu cuffs.[6] Some court dress of the Qing dynasty preserved features and characteristics which are distinct the clothing worn by the Manchu prior to the conquest of the Ming dynasty.[5]: 42 The Qing dynasty officials wore court dresses, which were also variants of Manchu clothing at the court.[5]: 41

Some court clothing worn in the Qing dynasty were also adopted from the Han Chinese's court clothing (especially from the Ming dynasty when the early Qing emperors adopted the Ming dynasty institutions and bureaucratic system[40]) but was refitted to show Manchu characteristics.[29] Court clothing also adopted the Han Chinese adornment designs and decorations (e.g. the use of Chinese dragons, the Twelve symbols of sovereignty),[29] and the use of the Five colours symbolism (e.g. the colour blue was adopted as the Manchu's dynastic colour while red was avoided as it had been the dynastic colour of the Ming dynasty).[25][40]

Formal court dress/ Lifu / Chaofu

Lifu (礼服, lit "ritual dress") were the ceremonial or formal court dress; they were characterized by matixiu cuffs[41]: 21–22 and were the most conservative in preserving Manchu clothing features.[5]: 41–42

Chaofu (朝服, lit. "court dress"), also known as "Audience robe",[42] or "Robe of State",[43] are official formal court dress (lifu). They are worn by the emperors and court officials on the most solemn state ceremonies; such as on the day of the Emperor's ascension on the throne, imperial weddings, birthdays, New Year, winter solstices, and sacrifices to Heaven and Earth.[29]

The Qing chaofu for men was developed based on the dress of the Ming dynasty court dress; it however had additional distinctive features, such as the Manchu matixiu cuffs in its chaopao, and plain cloth insertions at the sleeves, and the shape of the collar.[29] The chaofu of for men consists of a robe, called chaopao (lit. "court robe"); there was form of summer-style chaofu and two forms of winter-style chaofu.[25] The chaopao worn with the ceremonial collar, called piling (披领)[29] or pijian, around the neck.[25][44]: 22 The emperor, princes, noblemen and high officials wore hats, called chaoguan, which were regulated and worn accordingly to the seasons (winter and summer), ranks, and gender.[25] The colours were bright yellow for the emperor, apricot yellow (杏黃 xinghuang) for the heir apparent (crown prince); golden yellow (jinhuang, which looks closer to orange in colour rather than yellow) for other sons of the emperor.[25][note 5] The first to fourth degrees princes and imperial dukes had to wear blue, brown or any other colour unless the Emperor bestowed them with a golden yellow robe.[25] Blue black was the colour worn by the lower-ranking princes, noblemen, and high-ranking officials.[25]

| Rank | Description | Colour | Images | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter-style | Summer-style | ||||

| Emperor | 5-clawed dragon, including the twelve symbols[25][45]

The first winter style is similar to the summer-style chaofu but has is trimmed with fur.[25] The second winter-style is lined with sable on cuff, side-fastening edge, and collar. It was trimmed with a deep band of fur round the hem.[25] |

It is typically bright yellow (the colour reserved for the emperor), but the emperor was allowed to wear other colours; other colours of chaofu is also used if the ceremonial occasions requires it.[25] |

|

| |

|

| ||||

| First to fourth degrees princes and imperial dukes[25] | Blue |

|

|

||

| Between third degree prince and fourth degree official | The mid-18th century sumptuary laws stipulated that only the emperor and heir apparent could wear robes with five-clawed dragons, but in the 19th century, these regulations were often not observed.[42] Other people were actually supposed to wear four-clawed dragons robes (mangfu).[43] | Dark blue[42] chaopao with either 4-clawed or 5-clawed dragons |

| ||

| Qing nobles, high-ranking civil officials and military officials, and imperial guards. | Blue black chaopao with either 4-clawed or 5-clawed dragons[43] |

| |||

| |||||

Chaofu for women consisted of a chaopao, a chaogua (朝褂), and a skirt which is worn under the chaopao called chaoqun (朝裙).[25] The chaopao, is a formal court robe for women, which is characterized with L-shaped seamed between the collar and the underarm fastening.[46] The chaogua is a long-length court vest worn over the chaopao.[25] It has deep arm openings and sloping shoulder seams[47]: 58 and opens in the front.[25] It originated from a Ming dynasty vest worn by the Ming empresses; the deep cut arm openings and sloping shoulders however appears to have been derived from animal skin constructions.[25]

| Rank | Description | Images | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chaogua | Chaopao | ||||

| Winter | Summer | Winter | Summer | ||

| Empress dowager |

|

|

|||

| Empress |

|

| |||

|

|

||||

| Imperial noble consorts |

|

||||

| Noble consorts, consorts, imperial concubines |

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

| Consorts of the crown prince | The chaopao is ripe apricot (i.e. orange-yellow) in colour [46] |

| |||

| Imperial princess |

|

||||

Festive robe/ Jifu

Jifu (Chinese: 吉服; lit. 'Auspicious dress'), also known as festive robe, used for happy festivals and ceremonies (like a banquet).[48]

Jifu longpao and jifu mangpao

The jifu Dragon robes (Chinese: 龍袍; pinyin: longpao; 5-clawed dragons) and the jifu Python robes (mangpao; robes with 4-clawed dragons),[29][25] were used for various ceremonies (such as festival banquets and military inspections),[25][40][45] as semi-formal court dress. They were worn by the members of the imperial family and lower-ranking officials.[25] Prior to the 1759 sumptuary regulations, the jifu followed the Manchu-style cut and had to comply to the laws regarding colours and the dragon-claws number; however, the distribution of dragon patterns on the jifu were not regulated and the early Qing dynasty's robe followed the Ming tradition of having large curling dragons over the chest and back regions.[25] Women also wore jifu dragon robes and python robes as a semiformal court dress. By the mid-19th century, the matixiu (Chinese: 马蹄袖; pinyin: mǎtíxiù; lit. 'horse hoof cuff') sleeve cuffs of Manchu women's robe became wider and the size of the cuff also became bigger, particularly on the formal festive coats worn by Manchu court women.[7]

The 5-clawed dragons were used for the emperor, his heir apparent, the high-ranking princes and some lesser officials whom the emperor would bestow the 5-clawed dragons to them.[25] The 4-clawed dragons were worn by third ranking princes and anyone below this rank.[25] Those rules were eventually disregarded near the end of the Qing dynasty; and, jifu with five-claws dragons started to be worn by anyone regardless of ranks.[25]

The colours were bright yellow for the emperor, apricot yellow (杏黃 xinghuang) for the heir apparent (crown prince); golden yellow (jinhuang, which looks closer to orange in colour rather than yellow) for other sons of the emperor.[25][note 6] The first to fourth degrees princes and imperial dukes had to wear blue, brown or any other colour unless the Emperor bestowed them with a golden yellow robe.[25] Blue black was the colour worn by the lower-ranking princes, noblemen, and high-ranking officials.[25]

| Name | Rank | Description | Images | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longpao | Emperor | The emperor's jifu were decorated with the 12 symbols and were embroidered with a 5-clawed dragon; thus making it a dragon robe.[45] It is bright yellow, but it can also come in other colours. |

|

|

|

| |||

| Empress Dowager/ Empress |

|

| ||

| Imperial Crown prince | 5-clawed dragon.

It is apricot yellow (杏黃 xinghuang) in colour. |

|

| |

| Empress or lower rank imperial consort | Five-clawed golden dragons[49] |

|

||

| 5-clawed dragon, blue |

|

| ||

| 5-clawed, brown |

|

|||

| 5-clawed dragon |

|

|||

| 5-clawed dragon; blue black |

|

|||

| Name | Rank | Description | Images | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mangpao | 4-clawed dragon, blue |

|

||

Jifupao

On wedding and major family occasions unrelated to the court, jifupao (吉服袍[50]) typically have matixiu cuffs and were almost the same as jifu longpao/mangpao.[25] Noblemen women and wives of officials would wear robes with eight roundels with the Chinese character shou (Chinese: 壽; pinyin: shòu; lit. 'longevity') and other motifs; they were worn with a surcoat (jifugua) decorated with 8 roundels with shou or floral patterns.[25] Both the robe and surcoat could be decorated with or without lishui at the hem and cuffs.[25]

| Name | Rank | Description | Images | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jifupao | Noble women/ Wives of officials | Eight roundels with the Chinese character shou (Chinese: 壽; pinyin: shòu; lit. 'longevity' or other motifs; can be used for wedding.[25] |

|

|

|

| |||

|

| |||

| Roundels with crane and gourd (symbol of longevity), most likely used for birthdays.[51] |

|

|||

Longgua/ Jifu gua

Longgua, also known as jifu gua (吉服褂), was the woman's surcoat worn over a semi-formal dragon robe (jifu; i.e. the festive robe).[29][52] When the Manchu established the Qing dynasty, they incorporated roundels with dragons in their official court dress.[52] After the standardization of dress code in the mid 18th century, longgua with 8 dragon roundels became reserved for the empress dowager, empress, imperials concubines (first, second, and third ranks) and for the consort of the crown prince.[52]

| Name | Rank | Description | Images | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longgua | Empress Dowager |

| ||

| Empress |

|

|||

|

| |||

| Imperial consort |

|

|||

| Imperial princess |

|

|||

| Jifu gua | Wife of imperial prince/ high-ranking clan member/ Manchu official | Roundels with 5 cranes were possibly worn by the wife of an imperial prince, a high-ranking clan member, or a Manchu official, possibly worn for birthdays.[53] |

|

|

| Noble women/ Wives of officials | Eight roundels with the Chinese character shou (Chinese: 壽; pinyin: shòu; lit. 'longevity' or other motifs; can be used for wedding.[25] |

|

| |

| Roundels with crane and gourd (symbol of longevity), most likely used for birthdays.[54] |

| |||

Gunfu

Gunfu was a form of surcoat with circular embroidered roundel, which was part of the official court dress since 1759; it was worn over the chaofu or jifu.[25] It is calf-length and made of plain satin; it closes at the front.[25] It was worn by the imperial family; people from the higher ranks would wear five-clawed dragons which face to the front while those from the lower ranks would wear five-clawed dragons in profile.[25]

| Rank | Description | Images |

|---|---|---|

| Members of imperial family[25] | Four circular roundels (on the chest, back and shoulders).[25] |

|

| ||

| Noble |

|

Bufu

Bufu (Chinese: 補服; pinyin: Bǔfú) was worn with the jifu by the Qing dynasty Court officials (both military and civil)[5]: 42 [40][55] and by the Censorate Civil Bureaucrats.[56] The bufu was the man's surcoat with a square-shape court insignia, called buzi.[29] There is one rank insignia on the front and one on the back of the bufu.[55] Civil officials typically wear rank badges with bird designs; military officials wore rank badges with beasts (or animals) designs, and the Censorate Civil Bureaucrats wear rank badges with xiezhi.[55][56] The use of buzi on clothing is a continuation of the Ming dynasty court clothing tradition.[5]: 42 Women also wore bufu which would often be the mirror image found on the insignia used on her husband's bufu; therefore, when they sat together, the animals would face towards each other symbolizing marital harmony.[57][56]

Dragon or python would be worn on the buzi of the imperial dukes and noblemen.[25] Lower-ranking noblemen who were not allowed to wear clawed dragons would wear buzi with hoofed dragon near the end of the 19th century.[25]

| Rank | Description | Images | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imperial dukes or noblemen | Python/Mang |

|

||

| Civil officials wore rank badges with bird designs. | 1st rank | Crane |

|

|

| 2nd rank | Golden pheasant | |||

| 3rd rank | Peacock | |||

| 4th rank | Wild goose | |||

| 5th rank | Silver pheasant | |||

| 6th rank | Egret | |||

| 7th rank | Mandarin duck |

|

||

| 8th rank | Quail | |||

| 9th rank | Paradise flycatcher |

|

||

| Military officials | 1st rank | Qilin | ||

| 2nd rank | Lion | |||

| 3rd rank | Leopard | |||

| 4th rank | Tiger | |||

| 5th rank | Bear | |||

| 6th rank | Panther[note 7] | |||

| 7th rank | Panther/ Rhinoceros[note 8] | |||

| 8th rank | Rhinoceros[note 9] | |||

| 9th rank | Sea horse | |||

| Censorate Civil Bureaucrats[56] | Xiezhi | |||

Fur surcoats/ duanzhao (端罩)

Fur surcoats were typically worn by high-ranking officials over the winter jifu.[25]

-

Portrait of Shi Wenying wearing a fur surcoat.

-

Qing nobleman in winter coat, 1860s

-

Yinli wearing duanzhao

Ordinary dress (Changfu)/ casual dress (Bianfu)

Changfu (常服), also known as "ordinary dress",[25][5]: 41 Changfu was typically characterized by matixiu cuffs.[41]: 21–22 The informal official clothing was worn for occasions which are not major ceremonies or government business.[25] Semiformal non-official dress for women were lavishly decorated with embroidery and used contrasting borders by the mid-19th century reflecting the influence of Han Chinese culture.[25]

Bianfu (便服) are forms of ordinary wear,[5]: 41 used as everyday and leisure wear as casual clothing and were not regulated by the Qing court.[41]: 22 [58] They typically did not feature matixiu cuffs.[41]: 21–22

| Name | Rank/ gender | Description | Images | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changfu | Semiformal non-official | Bianfu | |||

| Changfu pao (常服袍)/ Neitao | Emperor | Neitao is long-sleeved and have narrow matixiu cuffs and 4 splits (side of robes, front and back) which provided greater ease of movement when mounting and dismounting their horses; it was originally a Manchu garment, made of plain long gown of silk.[25] They were mostly plain or self-patterned.[58] Structurally, it looks similar to the jifu; it is typically blue, grey, and reddish brown in colour.[25] There were no strict rules related to their colour. |

|

| |

| Military mandarin[25][note 10] |

|

||||

| Men |

|

| |||

| Changfu pao (常服袍) | Imperial women | Changfupao looked similar to the longpao jifu, with matixiu cuffs, they were made of plain silk (some had with embroidered dragons at the neck opening and sleeves).[25] It could be decorated with woven dragon roundels.[25] |

|

||

| Changyi (氅衣) | Women | A form of Manchu's women informal dress and leisure dress worn by imperial consorts.[58] They were worn with a long neck ribbon, called longhua.[29] The changyi had slits on both sides which facilitated body movements.[29] |

|

| |

|

| ||||

| Chenyi | Women | Chenyi is a type of Manchu's women informal dress and leisure clothing worn by imperial consorts; the dress is one-piece and has no slit on either sides.[1][58] It is round neck, with a panel of fabric which crosses from the left to the right side; it is fastened at the right side with 5 buttons and loops; they are relatively straight body shaped in cut and have full sleeves.[29] It was also worn with a long neck ribbon, called longhua.[29] |

|

| |

| |||||

|

| ||||

|

| ||||

| Phoenix robes | Empress/Empress dowager | The phoenix robe is worn by the Qing dynasty empress/ empress dowager.[59][22]: 180–181 They were worn as an informal court dress.[60] |

|

|

|

| Magua | Men | An over jacket for Manchu men; in the late 17th century, it became widespread for non-Manchu men in China.[61]: 299 The sleeves are elbow-length; the length of the magua could range from waist-length to knee-length; it has front opening.[26]: 9 |

|

||

|

|||||

| Men and women | Yellow magua |

|

|||

| Changfu gua (常服褂) | Men | A form of outerjacket with front opening which closes with button; it can be found in azurite blue colour (石青色) or black.[62] It is worn over the changfu robes (常服袍).[62] |

|

||

| Women |

|

||||

|

|||||

| Kanjia/ Majia | Women |

|

|||

|

|||||

| Informal vest for Manchu women |

|

||||

| The pipa vest is a common type of vest for Manchu women; its origins appear to be related to Manchu's informal magua, which was cut short on the front left side to facilitate horse mounting.[44]: 55 |

|

||||

| Men |

|

| |||

Xinfu

Xinfu (行服) are travel clothing which were typically used on surveying trips and hunting excursions which usually involves horse riding and archery. Most of xinfu are plain in colour and lacks elaborate decorations.[58]

Headwear and hairstyles

Hairstyles

- Liangbatou[35]: 62

- Qitou[2]

- Queue - It is the original male hairstyle of the Manchu; it was also a variant of the Jurchen queue.[35]: 60

Headwear

- Dianzi (鈿子) - Informal festive Manchu headdress, used for on festive occasions such as birthdays, ceremonies, and New Year celebrations.[25]

- Qing official headwear

-

Hat worn by a 6th-rank civil official, China, Qing dynasty, late 19th to early 20th century AD.

-

Dianzi purportedly belonging to Empress Dowager Cixi (Walters Art Museum)

-

"La concubine" by Jean Denis Attiret, with the subject (purportedly Step Empress) in winter-style (fur-lined) jifu. The hat is called jifuguan (吉服冠)

-

Detail of Empress Xiaozhuangwen's official portrait showing her chaoguan (朝冠) with kingfisher feather inlay

-

Detail of Princess Shouzang of the Second Rank (Daoguang Emperor's daughter)'s official portrait in winter-style chaofu

-

Detail of Empress Xiaoshurui's official portrait in winter-style chaofu

Footwear

Manchu women did not practice foot binding;[29][8]: 59 Banner women were also forbidden from adopting foot binding customs[5]: 41 although some Manchu women did transgress this rule.[8]: 341 Manchu shoes for Manchu women include Manchu platform shoes, which were used to emulate the bound feet gait of the Han Chinese.[8]: 341

Accessories

- Chaodai: A man's woven silk belt.[47]: 58

- Chaozhu

- Earrings: Manchu and Banner women wore three earrings at each ear (which was reinforced by Qianlong's edict of "一耳三鉗" (pinyin: yīěr sānqián; lit. 'one ear three pincers')) while Han Chinese women would wear a single earring.[5]: 41

- Fadu

- Lingtou: a small, plain, stiffed collar, which was worn over the collar of garments (such as surcoats, jifu and other informal clothing).[25]

- Longhua

- Piling (披领) – ceremonial collar.[29]

- Yajin

-

Piling collar

-

Detail of Empress Xiaogongren's official portrait showing three earrings on each ear (一耳三鉗)

-

Chaozhu, Qing dynasty court necklace.

Derivatives and influences

China

Changshan

The changshan, also known as changpao (lit. "long shirt/ long gown"), worn by the Han Chinese was a derivative of the Ming dynasty clothing[25] but was modelled after the Manchu men's robe.[1] It thus adopted Manchu clothing elements by slimming their Ming dynasty's changshan, by adopting the pipa-shaped collar, and by adopting the use of loops and buttons.[25] Compared to the neitao, the changshan was adapted to a sedentary lifestyle and thus only had two slits on the side instead four. and lacked the matixiu cuffs[25] The changshan was worn by Chinese men who did not engage in labour work.[1]

Cheongsam

The cheongsam was a derivative of the Manchu robe.[7]

Tangzhuang

Korea

Gallery

-

A young Manchu man dressed in traditional clothes.

See also

Notes

- ^ The mitigation policy stipulates 10 rules which are not all related to clothing: 1. Men had to shave and braid their hair and wear Manchu clothes, while women could wear their original hairstyle and wear hanfu; 2. A living man had to wear Manchu clothing, but after his death, he was allowed to be buried in Hanfu-style clothing; 3. There is no reason to follow the customs of the Manchu people for the affairs of the Underworld and can continue to follow Buddhist and Taoist customs; 4. The officials must wear Qing official uniforms but the slaves can still wear Ming style clothing; 5. A child does not need to follow the rules of Manchu but when he grows up, he needs to follow the rules of the Manchu; 6. Ordinary people have to wear Manchu clothing, shave their hair and wear braids, but Monks are allowed to wear Ming and Hanfu-style clothing; 7. prostitutes have to wear clothing required by the Qing court, but actors are free to wear clothes of other clothes due to the role of the ancients; 8. Official management follow the system of the Qing dynasty, while marriage ceremony keep the old system of the Han people; 9. The State title changed from Ming to Qing, but the official title names remain; Taxes and official services follow the Manchu system but the language remains Chinese.

- ^ In 1654, Chen Mingxia was impeached and executed for suggesting that the Qing court had to adopt Ming dynasty clothing in order to "bring peace to the empire". Liu Zhenyu was executed for urging the return of Ming style fashion under the reign of the Qianlong Emperor.

- ^ This size of dragon compared to the garment is a continuation of the Ming dynasty design style.

- ^ In 1175, it was observed that bondservant daughters were wearing a single pendant earring instead of three (which is the Manchu custom)

- ^ Although bright yellow was reserved for the Emperor, he was actually allowed to wear whatever other colours he wanted or wear the appropriate colours based on the occasions, e.g. the Emperor can wear blue robes when worshiping at the Altar of Heaven ceremony.

- ^ Although bright yellow was reserved for the Emperor, he was actually allowed to wear whatever other colours he wanted or wear the appropriate colours based on the occasions, e.g. the Emperor can wear blue robes when worshiping at the Altar of Heaven ceremony.

- ^ Prior to 1759, it was the symbol of both the 6th and 7th rank. From 1759, it became exclusively a representation of the 6th rank

- ^ Prior to 1759, it was symbolized by a panther.

- ^ Prior to 1759, only the 8th rank was represented by a rhinoceros

- ^ Neitao for military mandarin features an extra panel found at lower hem at the right side, which is fastened with loops and ball. This extra panel is removable, e.g. when horseback riding

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Han, Qingxuan (2019-01-01). "Qipao and Female Fashion in Republican China and Shanghai (1912-1937): the Discovery and Expression of Individuality". Senior Projects Fall 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tong, Ningning; Yuan, Songmei (2015). "Study of the Strategies for the Digital Communication of the Manchu Costumes under the Theory of Media Extension". Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Education, Management, Information and Medicine. Vol. 8. Atlantis Press. pp. 714–718. doi:10.2991/emim-15.2015.141. ISBN 978-94-6252-068-4.

- ^ a b c "Manchu Style". Chinese Traditional Dress - Online exhibitions across Cornell University Library. 2020-03-31. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Su, Wenhao (2019). "Study on the Inheritance and Cultural Creation of Manchu Qipao Culture". Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Art Studies: Science, Experience, Education (ICASSEE 2019). Atlantis Press. pp. 208–211. doi:10.2991/icassee-19.2019.41. ISBN 978-94-6252-837-6. S2CID 213865603.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Rawski, Evelyn Sakakida (1998). The last emperors : a social history of Qing imperial institutions. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21289-4. OCLC 37801358.

- ^ a b c d e f "The collection of Chinese clothing from the Qing Dynasty - National Museum in Krakow". mnk.pl. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Turn back your cuffs". John E. Vollmer. 2017-10-16. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g Smith, Richard J. (2015). The Qing Dynasty and traditional Chinese culture. Lanham. ISBN 978-1-4422-2192-5. OCLC 898910891.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f Keliher, Macabe (2020). The Board of Rites and the making of Qing China. Oakland, California. ISBN 978-0-520-97176-9. OCLC 1090283580.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Major, John S. (1993). Heaven and earth in early Han thought : chapters three, four and five of the Huainanzi. 安(前179-前122) 劉. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-1585-6. OCLC 26588471.

- ^ a b c d Fu, Yuguang (2020). Shamanic and mythic cultures of ethnic peoples in northern China. Andover. ISBN 978-1-003-13240-0. OCLC 1249021960.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Guo, Shuyun; 郭淑云 (2018). "Wubuxi ben ma ma" yan jiu (Di 1 ban ed.). Shenyang. ISBN 978-7-5652-2864-3. OCLC 1100443868.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Encyclopedia of Chinese history. Michael Dillon. New York, NY. 2016. ISBN 978-1-317-81716-1. OCLC 965196638.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Lee, Ki-baik (1984). A new history of Korea. Seoul Korea: Ilchokak, Publishers. ISBN 89-337-0204-0. OCLC 36540801.

- ^ a b Rawski, Evelyn Sakakida (2015). Early Modern China and Northeast Asia : Cross-Border Perspectives. Cambridge. ISBN 978-1-107-09308-9. OCLC 910239344.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b A new history of Parhae. John B. Duncan, Tongbuga Yŏksa Chaedan, Tongbuga Yo⁺їksa Chaedan. Leiden: Global Oriental. 2012. ISBN 978-90-04-24299-9. OCLC 864678409.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Zhu, Ruixi (2016). A social history of middle-period China : the Song, Liao, Western Xia and Jin dynasties. Bangwei Zhang, Fusheng Liu, Chongbang Cai, Zengyu Wang, Peter Ditmanson, Bang Qian Zhu (Updated ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-1-107-16786-5. OCLC 953576345.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b China : five thousand years of history and civilization. Lang Ye, Zhenggang Fei, Tianyou Wang. Kowloon, Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press. 2008. ISBN 978-962-937-467-9. OCLC 1142373741.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Johnson, Linda Cooke (2011). Women of the conquest dynasties : gender and identity in Liao and Jin China. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-6024-0. OCLC 794925381.

- ^ Mote, Frederick W. (1999). Imperial China, 900-1800. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-44515-5. OCLC 41285114.

- ^ a b Routledge Handbook of Imperial Chinese History. Victor Cunrui Xiong, Kenneth James Hammond. Abingdon, Oxon. 2019. ISBN 978-1-138-84728-6. OCLC 1031045844.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d 5000 years of Chinese costumes. Xun Zhou, Chunming Gao, 周汛, Shanghai Shi xi qu xue xiao. Zhongguo fu zhuang shi yan jiu zu. San Francisco, CA: China Books & Periodicals. 1987. ISBN 0-8351-1822-3. OCLC 19814728.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d e The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 6: Alien regimes and border states, 907–1368. Herbert Franke, Denis Crispin Twitchett, John King Fairbank. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1994. ISBN 978-1-139-05474-4. OCLC 317592785.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d e Roberts, John A. G. (2011). History of China (3rd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-24984-4. OCLC 930059261.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg Garrett, Valery M. (2007). Chinese dress : from the Qing Dynasty to the Present. Tokyo: Tuttle Pub. ISBN 978-0-8048-3663-0. OCLC 154701513.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vollmer, John E. (2007). Dressed to rule : 18th century court attire in the Mactaggart Art Collection. Mactaggart Art Collection. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press. ISBN 978-1-55195-705-0. OCLC 680510577.

- ^ a b c d e f g Schlesinger, Jonathan (2017). A world trimmed with fur : wild things, pristine places, and the natural fringes of Qing rule. Stanford, California. ISBN 978-1-5036-0068-3. OCLC 949669739.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Mailey, Jean (2013). The Manchu dragon : costumes of the Ch'ing dynasty, 1644-1912. [Lieu de publication non identifié]. ISBN 978-0-300-20157-4. OCLC 1040887449.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Chinese dress in the Qing dynasty". archive.maas.museum. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990 (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 217. ISBN 0521477719.

- ^ Majewicz, Alfred F., ed. (2011). Materials for the Study of Tungusic Languages and Folklore. Vol. 15 (illustrated, reprint ed.). Walter de Gruyter. p. 21. ISBN 978-3110221053.

- ^ Dwyer, Arienne M. (2007). Salar: A Study in Inner Asian Language Contact Processes, Part 1. Vol. 37 of Turcologica Series (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 22. ISBN 978-3447040914.

- ^ Wakeman, Frederic E. (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China, Volume 1. Vol. 2 of Great Enterprise (illustrated ed.). University of California Press,l. p. 868. ISBN 0520048040.

- ^ Lui, Adam Yuen-chung (1989). Two Rulers in One Reign: Dorgon and Shun-chih, 1644-1660. Faculty of Asian Studies monographs // The Australian National University (illustrated ed.). Faculty of Asian Studies, Australian National University. p. 37. ISBN 0731506545.

Dorgon did not want to see anything go wrong in a province and this might be the main reason why the government ... When the Chinese were ordered to wear the queue , Sun and Li took the initiative in changing their Ming hairstyle to ...

- ^ a b c Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2000). Manchus & Han : ethnic relations and political power in late Qing and early republican China, 1861-1928. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80412-5. OCLC 774282702.

- ^ "Velvet Textile for a Dragon Robe 17th century". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-05-20.

- ^ a b Steele, Valerie (1999). China chic : East meets West. John S. Major. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07930-3. OCLC 40135301.

- ^ Qian, Nanxiu (2001). Spirit and self in medieval China : the Shih-shuo hsin-y and its legacy. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-6442-2. OCLC 798298041.

- ^ Dong, Madeleine Yue (2003). Republican Beijing : the city and its histories. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92763-6. OCLC 52470842.

- ^ a b c d Heroldová, Helena (2016). "The Dragon Robe as the Professional Dress of the Qing Dynasty Scholar-Official (The Náprstek Museum Collection)". Annals of the Náprstek Museum. 37 (2): 49–72. doi:10.1515/anpm-2017-0012. ISSN 2533-5685. S2CID 191643762.

- ^ a b c d Silberstein, Rachel (2020). A fashionable century : textile artistry and commerce in the late Qing. Seattle. ISBN 978-0-295-74719-4. OCLC 1121420666.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c "Man's Audience Robe (Chaofu) Second half of the 19th century". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-05-16.

- ^ a b c "Robe of State 19th century China". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-05-16.

- ^ a b Finnane, Antonia (2008). Changing clothes in China : fashion, history, nation. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14350-9. OCLC 84903948.

- ^ a b c "Emperor's twelve-symbol festival robe China". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-05-14.

- ^ a b "Woman's Robe of State 18th century China". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-05-14.

- ^ a b Lewandowski, Elizabeth J. (2011). The complete costume dictionary. Dan Lewandowski. Lanham, Maryland. ISBN 978-0-8108-4004-1. OCLC 694238143.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Imperial dresses worn by concubines in the Qing Dynasty". en.chinaculture.org. p. 3. Retrieved 2022-05-21.

- ^ "Woman's Festival Robe late 19th century China". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-05-19.

- ^ "满族红绸五彩绣八团花蝶吉服袍". www.biftmuseum.com. Retrieved 2022-05-21.

- ^ "Birthday or Ceremonial Robe with Crane Medallions 19th century". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-05-21.

- ^ a b c "Festival Overcoat 18th century China". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-05-14.

- ^ "Woman's Surcoat (China)". Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Retrieved 2022-05-19.

- ^ "Woman's coat with crane medallions 19th century". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-05-21.

- ^ a b c "Mandarin Duck Rank Badge | Denver Art Museum". www.denverartmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-05-16.

- ^ a b c d "Exchange: Qing-dynasty rank badges at the University of Michigan". exchange.umma.umich.edu. Retrieved 2022-05-17.

- ^ "Leopard Rank Badge | Denver Art Museum". www.denverartmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-05-17.

- ^ a b c d e Guo cai chao zhang : Qing dai gong ting fu shi [The Splendours of Royal Costume: Qing Court Attire] (PDF). Hong Kong Museum of History, Hong Kong. Leisure and Cultural Services Department, Gu gong bo wu yuan, 故宮博物院. Xianggang: Kang le ji wen hua shi wu shu. 2013. ISBN 978-962-7039-77-8. OCLC 858272582.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "The Brief History of Qing Dynasty Clothing - 2022". www.newhanfu.com. 2020-05-22. Retrieved 2022-05-17.

- ^ Chinese court costumes. Royal Ontario Museum of Archaeology. Royal Ontario Museum of Archaeology. 1946. OCLC 976470860.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Fashion, identity, and power in modern Asia. Kyunghee Pyun, Aida Yuen Wong. Cham, Switzerland. 2018. ISBN 978-3-319-97199-5. OCLC 1059514121.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b "石青色缎常服褂". The Palace Museum. Retrieved 2022-05-20.

![Early design of the Qing dynasty dragon robe, 17th dynasty.[36][note 3]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/72/%E6%B8%85%E6%97%A9%E6%9C%9F_%E5%BD%A9%E7%B5%A8%E9%BE%8D%E8%A2%8D%E6%96%99-Velvet_Textile_for_a_Dragon_Robe_MET_DT5688.jpg/225px-%E6%B8%85%E6%97%A9%E6%9C%9F_%E5%BD%A9%E7%B5%A8%E9%BE%8D%E8%A2%8D%E6%96%99-Velvet_Textile_for_a_Dragon_Robe_MET_DT5688.jpg)