Contents

Arthur Otis Granger (February 14, 1846 – July 30, 1914) was an American industrialist and soldier. He manufactured and installed gasworks in Philadelphia and served as general manager of the United Gas Improvement Company, before serving as president of multiple fuel and gas light companies in the United States and Canada. He was later a mining engineer and railroad executive, and was reported to be a millionaire as of 1889. He established the Etowah Iron Company in Bartow County, had mining interests in South America, and was a business partner to Joseph M. Gazzam.

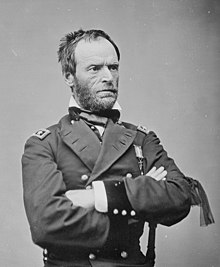

During the American Civil War, Granger was a private in the 15th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment, and became the secretary to General William Tecumseh Sherman. Granger served as part of the March to the Sea, and wrote the papers for General Joseph E. Johnston's surrender in 1865. Granger was an amateur astronomer, and his home included the largest observatory and telescope in the southeastern United States. He was a life member of the Franklin Institute, the American Institute of Mining Engineers, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the Royal Society of Arts.

Early life and military career

Arthur Otis Granger was born in Providence, Rhode Island, on February 14, 1846.[1][2][3] His parents were Sarah Rowan and the Reverend Arthur Granger,[4] the latter of whom died before Granger's birth.[3] In 1858, Granger began working as a cashier in a dry goods store in Philadelphia.[5]

At age 16 on September 8, 1862,[2] Granger enlisted as a private in the 15th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment for the Union Army during the American Civil War.[3][5] He participated in the Battle of Stones River under the command of General William Rosecrans.[2] Granger wrote in his memoirs that he was treated six weeks for typhoid fever at a hospital in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, as a result of the battle. While recovering, the hospital's operators learned of his legible handwriting, and assigned him to light duty as the chief clerk at the hospital for one year.[6] As a clerk, he served under General Washington Lafayette Elliott.[2]

After leaving the hospital, Granger reported for duty to General William Tecumseh Sherman. He departed from Atlanta on November 16, 1864, and was part of Sherman's March to the Sea.[6] Granger later became the private secretary to Sherman during the war.[1][3][7] Granger wrote that he was made a "confidential clerk" to Sherman upon arriving in Savannah, Georgia, and that he also served as Sherman's "private orderly" until his discharge in July 1865.[6] Granger wrote the papers for General Joseph E. Johnston's surrender to Sherman on April 26, 1865, then kept the inkstand and pen as mementos of the occasion.[6][8]

Industry and business career

After the war, Granger became an entrepreneur and mining engineer.[7] He was involved with the manufacture of gasworks for approximately 10 years as of 1886.[9] His A. O. Granger & Company of Philadelphia, was a subsidiary of United Gas Improvement Company as of 1883, and installed Lowe's process carburetted water gas devices.[3] He later served as general manager of the United Gas Improvement Company,[1] and was its president as of 1886.[5]

Granger was president of the Coney Island Fuel, Gas and Light Company as of 1886,[10] and was president of the Welsbach Light Company, and the Chautauqua Lake Railroad Company as of 1888.[5] He was one of several trustees to erect a building to serve as Presbyterian headquarters in Chautauqua, New York, in 1889.[11] He once operated a mercantile business in Helena, Montana, and was reported to be a millionaire as of 1889.[12]

During his Civil War service, Granger became familiar with the area near Cartersville.[7] He established the Etowah Iron Company in 1888, in Bartow County,[1][5] and owned 17,000 acres (6,900 ha) of iron ore mining lands in Georgia.[12] As of 1889, he also had mining interests in South America, and was associated with patent #779,091, for the "process of making silicofluoride of lead".[3] He was a business partner with Senator Joseph M. Gazzam, and operated the Dobbins mine in 1891. Granger constructed a railroad from the mine to the Etowah River 4 miles (6.4 km) away, where he also built a manganese processing facility. The Etowah Iron Company became the Blue Ridge Mining Company in 1900.[13]

In October 1893, Granger operated companies in Montreal and Halifax. In the same year, he was suspended as general manager of the Auer Incandescent Light Company in Montreal, amid charges that he forged power of attorney on customs documents for supplies imported from the United States.[14] Later in the year, he was re-elected manager of the company, began a libel suit against the stockholders who wanted to oust him, and a criminal suit charging conspiracy against him.[15] He later served as president of the company c. 1902 – c. 1909.[16][17]

Granger retired from business c. 1909 for health reasons.[1] At the time, he was also president of the American Gold Dredging Company, the Caribbean Company, and the Marles Carved Molding Company.[5]

Personal life

Granger married Caroline Dickson Gregory on August 15, 1870,[2][3] and subsequently lived in Philadelphia, Montreal, and Quebec.[2][18] They had six children, including five sons and one daughter.[2][3] His oldest son Henry, was a consular agent for the United States in Colombia, where he had mining and agricultural interests.[19] His second son William, was a businessman in Montreal, general manager and secretary of the Auer Incandescent Light Manufacturing Company,[16] and later president of the Montreal AAA, the Quebec Amateur Hockey Association, and the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association.[20]

The Grangers moved to Cartersville, Georgia, in 1890,[18] and purchased land on the hill where he camped while in the Union Army.[7] They lived at the west end of Main Street, later known as Granger Hill, and became involved in the social and cultural scene in Cartersville and Atlanta.[3] His wife was a founder and president of the Georgia Federation of Women's Clubs.[18] He was an amateur astronomer, took inspiration from the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, and entertained and educated house guests on astronomy.[21] He expanded his two-room house to include three floors and an observatory.[3] Their home, named "Overlook", included twenty-eight rooms and the largest observatory and telescope in the southeastern United States.[7][22]

Granger died on July 30, 1914, in Philadelphia.[1][5][23] He had taken a trip to New York City a month prior to his death, then took ill and briefly recovered.[1] His cause of death was listed as diabetes, and complications from cardiac fibrosis.[4] He was interred at Mount Moriah Cemetery in Philadelphia.[4][24]

Honors and legacy

Granger was a life member of the Franklin Institute, the American Institute of Mining Engineers, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the Royal Society of Arts.[5]

He was posthumously recognized with a scholarship in his name, donated by his widow at the Tallulah Falls Industrial School.[18] His telescope was sold to a traveling circus, and later purchased by the University of Texas at Austin. His observatory was moved to Agnes Scott College in Atlanta.[7]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "Private Secretary of Sherman is Dead". The Montgomery Daily Times. Montgomery, Alabama. August 3, 1914. p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Granger, James Nathaniel (1893). Launcelot Granger of Newbury, Mass., and Suffield, Conn. Ripol Classic. pp. 475–476. ISBN 9785880057696.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Smith, Tony. "Overlook Scope". Lowndes County Historical Society Museum. Valdosta, Georgia. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c Deardorff, Nora R. (July 31, 1914), City of Philadelphia Death Certificate, Registered number:18600, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Bureau of Vital Statistics, Department of Health

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Arthur Otis Granger Dies". The New York Times. New York, New York. July 31, 1914. p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Granger, Arthur O. "15th Regiment Cavalry Pennsylvania Volunteers: The Fifteenth at General Joe Johnston's Surrender". Pennsylvania Roots. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Arthur Otis Granger". Etowah Valley Historical Society. 2019. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "An Historic Inkstand". Knoxville Sentinel. Knoxville, Tennessee. New York Press. February 9, 1899. p. 4.

- ^ "Safety and Economy". The Boston Daily Globe. Boston, Massachusetts. February 4, 1886. p. 13.

- ^ "Annual Report of the Coney Island Fuel, Gas and Light Company". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. January 19, 1886. p. 5.

- ^ "A New Religious Association". The Post-Star. Glens Falls, New York. August 29, 1889. p. 4.

- ^ a b "Granger's Success". Helena Weekly Herald. Helena, Montana. August 8, 1889. p. 8.

- ^ Cunyus, Lucy Josephine (2001). History of Bartow County, Georgia (PDF). Greenville, South Carolina: Southern Historical Press. pp. 201–202. ISBN 9780893080051 – via United States Genealogy Network.

- ^ "Defrauded An Inventor". Cincinnati Commercial Gazette. Cincinnati, Ohio. September 27, 1893. p. 4.

; "Arrested For Conspiracy". The Boston Post. Boston, Massachusetts. October 5, 1893. p. 1.

; "Arrested For Conspiracy". The Boston Post. Boston, Massachusetts. October 5, 1893. p. 1.

- ^ "Granger Gains The Day". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. October 15, 1893. p. 5.

- ^ a b "Mr. Granger Re-elected President of Auer Co". The Gazette. Montreal, Quebec. April 17, 1902. p. 9.

- ^ 61st United States Congress (June 25, 1909), "Chapter 4", Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 61st Congress, vol. 44, Washington, DC: United States Government Publishing Office, p. 3812

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Mrs. Arthur Granger Is Claimed By Death". The Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia. February 8, 1937. p. 18.

- ^ "Asks Senator's Arrest". New-York Tribune. New York, New York. November 9, 1905. p. 11.

- ^ "William R. Granger Died in 52nd Year". The Gazette. Montreal, Quebec. April 25, 1925. p. 4.

- ^ "A Well-timed Telescope". The Morning Post. Camden, New Jersey. August 3, 1914. p. 6.

- ^ "Largest Observatory in South Located in Granger Home in Cartersville". The Atlanta Constitution. Atlanta, Georgia. February 2, 1908. p. 1.

- ^ "Granger". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. August 1, 1914. p. 6.

- ^ "Arthur Otis Granger". Friends of Mount Moriah Cemetery. 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.