Contents

| Part of a series on the |

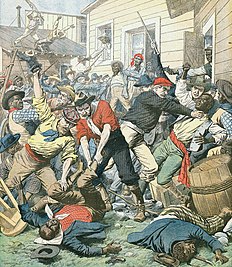

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

|

The lynching of Isadore Banks occurred in Marion County, Arkansas, in 1954. No investigation ever occurred and no murderers were found.[1]

Isadore Banks was a wealthy African-American man in Arkansas. Nobody was ever charged for his death, and it remains one of the cold cases of the Civil Rights era.[2]

Isadore Banks

Isadore Banks was a land-owning veteran of World War I. He was born on July 15, 1895, when racial violence in Arkansas was rising.[2] During this time period of lynchings, African Americans were removed from politics and silenced.[2] Jim Crow laws contributed to this, allowing white people to treat African Americans with contempt.[2]

In 1918, Banks joined the U.S. Army. After the war's conclusion, he returned to Arkansas and worked for a utility company.[2] Numerous race riots in 1919 and the return of the Ku Klux Klan to Arkansas led to African Americans organizing throughout the area.[2] Through all of this, Banks rose to become "a prominent and respected leader, a Freemason, and one of the wealthiest African-American landowners in this region of Arkansas."[2] He provided support to other black farmers in the form of tools or farm supplies, along with supporting local black schools.[2]

Lynching

Isadore Banks disappeared on June 4, 1954. His body was found on June 8, "mutilated and burned beyond all recognition."[2] He was identified by the presence of his empty truck nearby, with "his loaded shotgun and coat still inside." Banks had been tied or chained to a tree, doused in fuel, and set on fire from the knees up, leaving behind very little. No evidence as to who murdered him was found.

Reaction and aftermath

Local law enforcement did not pursue the case, leaving it to gather dust. The Grant Co-Op Gin, a group of prominent black citizens of the county which Banks was a member of, offered a reward for any information, but none was ever provided.[2] The NAACP also tried to help the investigation, but still nothing was done to try and find Banks's murderers. Julian Fogleman, the civil attorney for Marion at the time, "could not recall whether a coroner's inquiry was even performed."[2]

Banks's death had a marked impact on his community. In the aftermath of his death, community members checked in on each other and tried to piece together what had happened amongst themselves.[3] The lynching also succeeded in scaring the black populace; fears that white people would descend upon them and kill them for any perceived slight rose, along with fears for their children.[3] His death was also a heavy blow to the organization of African-Americans in Crittenden County.[1]

Multiple theories exist as to the reason for his murder. One posits that Banks had repeatedly rejected offers to sell his land to white farmers, who were "angered by his repeated refusals and became violent."[2] The second holds that he was renting land from "a white woman," and was killed by white farmers who wanted access to it. Yet another theory suggests that Banks had been romantically involved with a white woman, a common trope used across lynchings. Mirroring that, it has also been suggested that Banks "had an altercation" with some white men who had propositioned his daughter, leading to his murder.[2] Finally, it is possible he was murdered for being too successful as a black man in the South.[1]

Pop culture significance

In 2020 a podcast called Unfinished: Deep South was released by Market Road Films and Stitcher Radio about Isadore Banks's death. The podcast, produced by Taylor Hom and Neil Shea and spanning 10 episodes, attempted to determine who had actually committed the murder by going to Marion and meeting the surviving members of Isadore's family.

The podcast covered a wide variety of topics important to the event, including the Jim Crow South and what a lynching is.[4] It also interviewed many of the townsfolk who still lived in the town. While some people in the town did seem to know who had killed Banks, they either did not speak for fear of a lawsuit or were simply drunk.

See also

Citations

- ^ a b c "May 2019 – UAB Institute for Human Rights Blog". sites.uab.edu. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Encyclopedia of Arkansas". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ a b Portwood, Shirley J. (1999). "In Search of My Great, Great Grandparents: Mapping Seven Generations of Family History". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 92 (2): 95–118. ISSN 1522-1067. JSTOR 40193211.

- ^ "Unfinished: Deep South". www.stitcherstudios.com. Retrieved March 22, 2024.