Contents

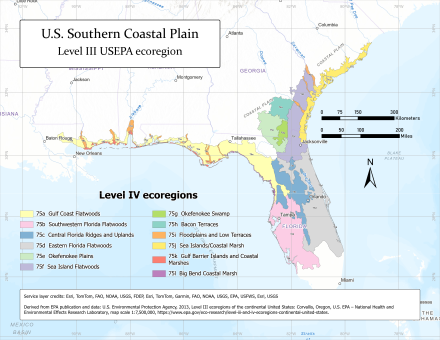

The North American Southern Coastal Plain is a Level III ecoregion designated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in six U.S. states. The region stretches across the Gulf coast from eastern Louisiana to Florida, forms the majority of Florida, and forms the coastlines of Georgia and much of South Carolina. It has been divided into twelve Level IV ecoregions.

Description

Terrain

Mostly flat plains, the region also includes barrier islands, coastal lagoons, marshes, and swampy lowlands along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts. In Florida, an area of more rolling discontinuous highlands contains numerous lakes. This ecoregion is lower in elevation with less relief and wetter soils than the Southeastern Plains ecoregion to the north. Ultisols, Spodosols, and Entisols are common, with thermic and hyperthermic soil temperature regimes and aquic and some udic soil moisture regimes.[1] Orlando

Climate

The ecoregion has a mild mid-latitude humid subtropical climate, characterized by hot humid summers and warm to mild winters.[1] In the Köppen climate classification scheme, the area is classified within Cfa: humid subtropical climates.[2] The mean annual temperature is approximately 19 °C (66 °F) to 22 °C (72 °F). The frost-free period ranges from 280 to 360 days. The mean annual precipitation is 1,338 millimetres (52.7 in), ranging from 1,170 millimetres (46 in) to 1,650 millimetres (65 in).[1]

Hydrology

In the Southern Coastal Plain, there are numerous low-gradient, perennial streams and large rivers, wetlands, and lakes.[1]

Major waterways include:

- Tangipahoa River

- Pearl River

- Pascagoula River

- Mobile River (coastal)

- Apalachicola River (south of 30°18' N)

- Alapaha River

- Suwanee River

- Santa Fe River

- Peace River

- St. Johns River

- Altamaha River (east of 81°56' W)

- Savannah River (southern half)

- Canoochee River

- Edisto River (coastal)

Major wetlands and lakes include:

- Tate's Hell Swamp

- California Swamp

- Lake Harris

- Lake Apopka

- Lake Istokpoga

- Lake Kissimmee

- Lake Tohopekaliga

- Lake George

- Okefenokee Swamp

Vegetation

Once covered mainly by longleaf pine flatwoods and savannas, this ecoregion also had a variety of other communities that supported slash pine, pond pine, pond cypress, beech, sweetgum, southern magnolia, white oak, and laurel oak forest. Near rivers, there are southern floodplain forests with bald cypress, pond cypress, water tupelo, bottomland oaks, sweetgum, green ash, and water hickory.[1]

Wildlife

Common species of the Southern Coastal Plain ecoregion include black bear, white-tailed deer, bobcat, marsh rabbit, fox squirrel, manatee, egret, blue heron, red-cockaded woodpecker, indigo bunting, Florida scrub jay, box turtle, gopher tortoise, southern dusky salamander, scrub lizard, cottonmouth, and alligator.[1]

Land Use/Human Activities

Human land uses of this region include pine plantations and forestry, pasture for beef cattle, citrus groves, tourism and recreation, and fish and shellfish production. There are some large areas of urban, suburban, and industrial uses. Larger cities from north to south include Georgetown, Charleston, Savannah, Waycross, Brunswick, Jacksonville, Hammond, Slidell, Gulfport, Biloxi, Pascagoula, Mobile, Pensacola, Gainesville, Ocala, Orlando, Tampa, St. Petersburg, and Fort Myers.[1]

Level IV ecoregions

Gulf Coast Flatwoods (75a)

In Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, the Gulf Coast Flatwoods is a narrow region of nearly level terraces and delta deposits composed of Quaternary sands and clays. Wet, sandy flats and broad depressions that are locally swampy are usually forested, while some of the better-drained land has been cleared for pasture or crops.[4]

In Florida, the Gulf Coast Flatwoods expand into a wider area, which borders the central uplands (75c) on the east, sharing the same southern terminus as the Big Bend Coastal Marsh (75l) just north of Tampa.

Settlements in the Gulf Coast Flatwoods include Hammond, Slidell, Gulfport, Biloxi, Mobile, Pensacola, and Panama City. Protected areas include Bogue Chitto National Wildlife Refuge, Apalachicola National Forest, and Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge.

Southwestern Florida Flatwoods (75b)

The Southwestern Florida Flatwoods are a relatively large region of flat topography, sandy soils, and pine scrub dominated by saw palmetto, with pockets of wetland. Brush fires have been important to maintaining this environment and preventing the formation of oak hammocks.[5] Tree species include slash pine, longleaf pine, pond cypress, bald cypress, oak, maple, southern magnolia, gum and hickory.[6] Compared to the Eastern Florida Flatwoods (75d), this region has relatively more xeric upland sands and mining/post-mining soils, and less wetland soil and open water.[7] Vulnerable wildlife species found in the area include Florida panther, Florida black bear, sandhill crane, wood stork and gopher tortoise.[8]

Settlements in the Southwestern Florida Flatwoods include Tampa, Clearwater, St. Petersburg, Sarasota, Port Charlotte, Cape Coral, Lehigh Acres, Immokalee, and the coastal edges of Bonita Springs and Naples. There are numerous (though individually small) protected areas within the region, such as the Withlacoochee State Forest, J. N. "Ding" Darling National Wildlife Refuge, Myakka River State Park, and Okaloacoochee Slough State Forest.

Central Florida Ridges and Uplands (75c)

The Central Florida Ridges and Uplands, also called Florida longleaf pine sandhills, are a sandy, elevated, somewhat disjunct region created by marine deposits. The ridges run north–south in the center of the Florida peninsula. An example of sandhills, the region is generally dry and prone to brush fires because of the fast-draining soil, with sandier, faster-draining soil in more abundance at higher elevations.[9][7] Cities in the Central Florida Ridges and Uplands include Gainesville, Ocala, Deltona, Orlando, and Lakeland. The area includes the Ocala National Forest, the Withlacoochee State Forest, Walk-In-The-Water Wildlife Management Area, and Lake Wales Ridge State Forest.

The region's southern half, latitudinally, extends southeastward from Lake Harris in a narrow ridge, called the Lake Wales Ridge, terminating near the boundary between Highlands and Glade Counties. The ridge is primarily composed of xeric upland sands, falling into adjacent, poorly draining flatwoods (75b and 75d) on either side, averaging 11.7 kilometres (7.3 mi) in width.[7] Elevation of the Lake Wales Ridge typically varies from 38 to 65 metres (125 to 213 ft) above mean sea level.[10] Sugarloaf Mountain, the highest point in peninsular Florida at 95 metres (312 ft), lies within the Lake Wales Ridge. Native vegetation was scrub with white oak, red oak, Archbold oak, Chapman oak, sand live oak, myrtle oak, turkey oak, scrub hickory, slash pine, sand pine, Florida rosemary, saw palmetto, scrub palmetto, and cutthroat grass (endemic to central Florida).[7][4] Florida's only endemic bird, the Florida scrub jay, and only endemic mammal, the Florida mouse, are extant on the Lake Wales ridge.[7] The Florida sand skink, a species with vulnerable conservation status, is endemic to the Central Florida Ridges and Uplands.[9] Approximately 78% of the ridge's xeric uplands had already been developed by the late 1980s. Human land use includes pasture, citrus groves, pine plantations, sand mining, and residential areas.[7][9]

Eastern Florida Flatwoods (75d)

The Eastern Florida Flatwoods are a region extending from Lake Okeechobee in the south to the St. Johns River estuary in the north, though not quite so far as Jacksonville. The region transitions into sandhill (75c) to the west, and features sandy beaches and Atlantic barrier islands on the eastern side. Compared to the Southwestern Florida Flatwoods (75b), this region has relatively more wetland soil and open water, and less xeric upland sands and mining/post-mining soils.[7] Etonia rosemary is an endangered plant endemic to the region.[11] The now-extinct dusky seaside sparrow was endemic to the region.[12]

Settlements in the Eastern Florida Flatwoods include St. Augustine Beach, Elkton, Palatka, Florahome, Georgetown, Flagler Beach, Daytona Beach, Kissimmee, Palm Bay, and Port St. Lucie. Protected areas include Etoniah Creek State Forest, Matanzas State Forest, Tiger Bay State Forest, Lake George State Forest, Lake Woodruff National Wildlife Refuge, St. Johns National Wildlife Refuge, Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, Everglades Headwaters National Wildlife Refuge and Conservation Area, and J.W. Corbett Wildlife Management Area.

Okefenokee Plains (75e)

The Okefenokee Plains consist of flat plains and low terraces developed on Pleistocene–Pliocene sands and gravels. These plains have slightly higher elevations and less standing water than 75g (Okefenokee Swamp), although there are numerous swamps and bays. Soils are somewhat-poorly to poorly drained. The region has mostly coniferous forest and young pine plantation land cover, with areas of forested wetland.[4]

Sea Island Flatwoods (75f)

The Sea Island Flatwoods are poorly-drained flat plains with lower elevations and less dissection than the adjacent Atlantic Southern Loam Plains (65l). Pleistocene sea levels rose and fell several times creating different terraces and shoreline deposits. Spodosols and other wet soils are common, although small areas of better-drained soils add some ecological diversity. Trail Ridge is in this region, forming the boundary with 75g. Loblolly and slash pine plantations cover much of the region. Water oak, willow oak, sweetgum, blackgum and cypress occur in wet areas.[4]

Okefenokee Swamp (75g)

The Okefenokee Swamp is a mixture of forested swamp and freshwater marsh with some pine uplands. With Trail Ridge at its eastern boundary, the swamp drains to the south and southwest and contains the headwaters for the St. Marys and Suwannee Rivers. The swamp contains numerous islands, lakes, and thick beds of peat. The slow-moving waters are tea-colored and acidic. Cypress, blackgum, and bay forests are common, with scattered areas of prairie, which are composed of grasses, sedges, and various aquatic plants. Most of this region is within the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge.[4]

Bacon Terraces (75h)

The Bacon Terraces include several relatively flat, moderately dissected terraces with subtle east-facing scarps. The terraces, developed on Pliocene–Pleistocene sands and gravels, are dissected in a dendritic pattern by much of the upper Satilla River basin. Cropland is mostly on the well-drained soils on the long, narrow, flat to gently sloping ridges paralleling many of the stream courses. The broad flats of the interfluves are often poorly drained and covered in pine, while bottomland forests are found in the wet, narrow floodplains.[4]

Floodplains and Low Terraces (75i)

Floodplains and Low Terraces are a continuation of the riverine Southeastern Floodplains and Low Terraces (65p) ecoregion across the Southern Coastal Plain. The broad floodplains and terraces of major rivers, such as the Savannah, Ogeechee, Altamaha, and Mobile–Tensaw, make up the region. Composed of stream alluvium and terrace deposits of sand, silt, clay, and gravel, along with some organic muck and swamp deposits, the region includes large sluggish rivers and backwaters with ponds, swamps, and oxbow lakes. River swamp forests of bald cypress and water tupelo and oak-dominated bottomland hardwood forests provide important wildlife habitat.[4]

In South Carolina, the Floodplains and Low Terraces are similar to the Mid-Atlantic Floodplains and Low Terraces (63n) ecoregion which lie in the state's river valleys, such as those of the Edisto River, the Santee River, and the Waccamaw River.[13]

Sea Islands/Coastal Marsh (75j)

The Sea Islands/Coastal Marsh region is a highly dynamic environment affected by ocean wave, wind, and river action.[4] Quaternary unconsolidated sand, silt, and clay has been laid down as beach, dune, barrier beach, saline marsh, terrace, and nearshore marine deposits. Mostly sandy soils occur on the barrier islands, while organic and clayey soils occur in the freshwater, brackish, and salt marshes.[13] Maritime forests of live oak, red cedar, slash pine, and cabbage palmetto grow on parts of the sea islands, and various species of cordgrass, saltgrass, and rushes are dominant in the marshes.[4] The islands' dunes are dominated by sea oats, which play a primary role in stabilizing the dune. Other dune plants include bayberry, dogfennel, bitter panic grass, broomsedge, wax myrtle, and Spanish bayonet.[13]

The island, marsh, and estuary systems form an interrelated ecological web, with processes and functions valuable to humans, but also sensitive to human alterations and pollution. The coastal marshes, tidal creeks, and estuaries are important nursery areas for fish, crabs, shrimp, and other marine species. Charleston Harbor is one of the largest container ship ports on the East Coast, and it also contains one of the largest commercial shrimp fisheries in the state, raising concerns about the health of the estuary, coastal marshes and associated flora and fauna. The Sea Islands region has a long history of human alterations. Native Americans cultivated corn, melons, squash, and beans on some of these islands. During the colonial and antebellum periods in the 1700s and 1800s, a plantation agriculture economy dominated the region, producing rice, indigo, and Sea Island cotton. While parts of the this region are now managed as wildlife refuges or estuarine research reserves, the expanding resort economy continues to broadly change land uses, water quality, and the once more isolated Gullah and Sea Island cultures.[13]

Gulf Barrier Islands and Coastal Marshes (75k)

The Gulf Barrier Islands and Coastal Marshes region contains salt and brackish marshes, dunes, beaches, and barrier islands that enclose the Mississippi Sound and Mobile Bay. Cordgrass and saltgrass are common in the intertidal zone, while xeric coastal strand and pine scrub vegetation occurs on parts of the dunes, spits, and barrier islands. Dauphin Island, one of Alabama's best birding sites, is known for the many trans-gulf migrant bird species that can be seen in spring and fall.[4]

In Louisiana, the sediments of this region are associated more with the Pearl River than Mississippi River deltaic deposits. The region east of Louisiana has salt and brackish marshes, dunes, beaches, and barrier islands. In Louisiana, tidal freshwater marshes occur, such as those on the delta plains of the larger rivers.[14]

Big Bend Coastal Marsh (75l)

The Big Bend Coastal Marsh is an extremely narrow but long region, following the Gulf coast beginning near the mouth of the Ochlockonee River (near 29° 45' N, 85° W), until just north of Tampa Bay (near 28° 14' N, 82° 45' W), a distance of approximately 280 miles (450 km), but typically penetrating only 0.5 to 1.5 miles (0.80 to 2.41 km) inland from the shore. The Big Bend marsh constitutes "the largest remaining stretch of undeveloped coastline in the continental United States"[15] as well as "the second-largest contiguous seagrass meadow in the continental United States."[16] A karst shelf is layered over with poorly draining organic soil. The Suwanee River is the largest contributor of freshwater to the ecoregion, with a discharge volume of 9460 million cubic meters, roughly 82% of freshwater inflow.[15][16]

The marsh is dominated by seagrasses, namely turtlegrass, manateegrass, and shoalgrass, with occasional stargrass, widgeongrass, and paddlegrass.[16] Oyster reefs are present in some areas and act as a food source for shorebirds such as American oystercatchers.[17]

The Big Bend Coastal Marsh generally transitions to the Gulf Coast Flatwoods (75a), which may be piney forest or swamp depending on inflow of freshwater and soil drainage. Adjacent swamps, and the coastal marsh in general, are very sensitive to tidal flooding (and baseline sea level rise), saltwater intrusion, aquatic pollution, tropical cyclones, and cold snaps (whose frequency has increased due to anthropogenic climate change). Authors of a 2018 satellite-imagery-based study characterized regional forests' status as experiencing "accelerated die-off."[15] Authors of a 15-year seagrass study which concluded in 2022 characterized Southern Big Bend's 45% decline in seagrass cover as "alarming."[16]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Griffith, Glenn (2010-05-11). "Level III North American Terrestrial Ecoregions: United States Descriptions". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Beck, Hylke E.; Zimmermann, Niklaus E.; McVicar, Tim R.; Vergopolan, Noemi; Berg, Alexis; Wood, Eric F. (2018-10-30). "Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution". Scientific Data. 5 (1). Bibcode:2018NatSD...580214B. doi:10.1038/sdata.2018.214. ISSN 2052-4463. PMC 6207062. PMID 30375988.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Weather Service. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Griffith, Glenn E.; Omernik, James M.; Comstock, Jeffrey A.; Lawrence, Steve; Martin, George; Goddard, Art; Hulcher, Vickie J.; Foster, Trish (2001). "Ecoregions of Alabama and Georgia" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- ^ "Pine Flatwoods". University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ "Withlacoochee State Forest". Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g Weekley, Carl W.; Menges, Eric S.; Pickert, Roberta L (Winter 2008). "An Ecological Map of Florida's Lake Wales Ridge: A New Boundary Delineation and an Assessment of Post-Columbian Habitat Loss". Florida Scientist. 71 (1): 45–64. JSTOR 24321468 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "Okaloacoochee Slough State Forest". Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ a b c Mushinsky, Henry R.; McCoy, Earl D. (2017). "Partners in Three Decades of Conservation Research in Florida". Journal of Herpetology. 51 (3): 287–296. doi:10.1670/16-015 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Abrahamson, Warren G.; Layne, James N. (2003). "Long-term Patterns of Acorn Production for Five Oak Species in Xeric Florida Uplands". Ecology. 84 (9): 2476–2492. Bibcode:2003Ecol...84.2476A. doi:10.1890/01-0707.

- ^ "Conradina etonia". NatureServe Explorer. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ "St. Johns National Wildlife Refuge". United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d Griffith, Glenn; Omernik, James; Comstock, Jeffrey (2002-07-31). "Ecoregions of South Carolina: Regional Descriptions". United States Environmental Protection Agency.

- ^ Daigle, Jerry J.; Griffith, Glenn E.; Omernik, James M.; Faulkner, Patricia L.; McCulloh, Richard P.; Handley, Lawrence R.; Smith, Latimore M.; Chapman, Shannen S. (2006). "Ecoregions of Louisiana" (PDF). Retrieved 2024-03-12.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c McCarthy, Matthew; Dimmitt, Benjamin; Muller-Karger, Frank (2018-10-31). "Rapid Coastal Forest Decline in Florida's Big Bend". Remote Sensing. 10 (11): 1721. Bibcode:2018RemS...10.1721M. doi:10.3390/rs10111721. ISSN 2072-4292.

- ^ a b c d Yarbro, L. A.; Carlson, P. R.; Johnsey, E. (2023-12-16). "Extensive and Continuing Loss of Seagrasses in Florida's Big Bend (USA)". Environmental Management. 73 (4): 876–894. Bibcode:2023EnMan..73..876Y. doi:10.1007/s00267-023-01920-y. ISSN 0364-152X. PMID 38103093.

- ^ Vitale, Nick; Brush, Janell; Powell, Abby (June 2021). "Loss of Coastal Islands Along Florida's Big Bend Region: Implications for Breeding American Oystercatchers". Estuaries and Coasts. 44 (4): 1173–1182. Bibcode:2021EstCo..44.1173V. doi:10.1007/s12237-020-00811-3. ISSN 1559-2723.