Contents

Fort Hull was an earthen fort built in present-day Macon County, Alabama in 1814 during the Creek War.[1] After the start of hostilities, the United States decided to mount an attack on Creek territory from three directions. The column advancing west from Georgia built Fort Mitchell and then clashed with the Creeks. After a pause in operations, the column from Georgia continued its march and built Fort Hull. The fort was used as a supply point and was soon abandoned after the end of the Creek War.

History

Background

The Creek War began after factions of the Creek tribe joined forces in opposing the United States and allied Choctaw, Cherokee, and Creek warriors. The Creeks who were hostile to the United States, known as Red Sticks, were angered over the consolidation of tribal government and selling of traditional tribal lands. The American-allied Creeks, known as White Sticks, were engaged in a civil war with the Red Sticks prior to United States involvement. After the start of the War of 1812, the United States hoped to prevent Great Britain from allying with and supplying the Red Sticks. In response to their attacks on settlers, the United States began a military campaign against the Red Sticks in 1813.[2]

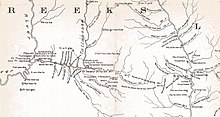

After the Fort Mims massacre, the United States planned a three-pronged attack on the Creek heartland. The initial plan called for troops to march south from Tennessee under the command of Andrew Jackson, east from Georgia under the command of John Floyd, and up from the southwest under Ferdinand Claiborne. Along with White Sticks under the command of William McIntosh, Floyd set out from Georgia in the later part of 1813. After crossing the Chattahoochee River, his troops constructed Fort Mitchell. Floyd's forces continued marching westward, culminating in the Battle of Autossee. Floyd was injured in the battle and his forces retreated back to Fort Mitchell.[2]

After recuperating, gathering supplies, and raising new recruits, Floyd left Fort Mitchell on January 17, 1814 with eleven hundred Georgia militia, six hundred allied Creeks, and cannons.[3] Floyd's force marched westward along the Federal Road, planning to construct forts to protect their extended supply lines.[2] Travel was slow due to recent rains, so on January 20 Floyd made the decision to stop near the junction of Persimmon Creek and Calebee Creek and construct a fort to serve as the first supply point.[3][4]

Construction

Captain Jett Thomas, an engineer officer and artillery commander, led the construction of Fort Hull.[5] The fort was named for Commodore Isaac Hull.[6] No drawing or description of Fort Hull exists, but it is likely it was built in a similar style to other forts built on the Federal Road (such as Fort Bainbridge), with an earth work surrounded by a palisade.[7] The fort likely had at least one blockhouse, officers quarters, and a magazine.[6] A spring that fed into Persimmon Creek was used as the water source for the fort.[8]

Fort Hull was constructed over four days.[9] The four days of construction allowed the roads leading to and from the fort to dry, but construction was also slow due to rationing. In protest over lack of rations and entrenching tools, troops slowed their work. This forced Floyd to reinstate full rations prior to completion of the fort.[4]

While the fort was being constructed Captain John P. Harvey was ordered by Floyd to lead a raid on the plantation of Alexander Cornells, Benjamin Hawkins' former interpreter. Cornells' daughter had led runaway slaves to the plantation with plans to rally other slaves to help the Red Sticks. Harvey's raid captured Cornells' daughter and nine slaves and brought them back to Fort Hull.[10]

Military use

On January 25, Floyd felt the Federal Road was passable, so he set out for the Creek town of Tukabatchee and left one hundred men in charge of Fort Hull.[10] Fort Hull was located 15 mi (24 km) to the east of Tukabatchee[11] and 24 mi (39 km) east of the Creek town of Hoitlewaule (also spelled as Othlewallee or Hoithlewalli).[12] American commanders were concerned that Red Stick warriors were concentrating in these two towns and planned to attack the towns as soon as possible.[10] En route to Tukabatchee Floyd's forces were slowed down by obstructions placed in the road by Red Sticks. The delay (in combination with the plan to attack the Red Sticks from an unexpected direction) led Floyd to leave the Federal Road and march northward. The force was slowed down by swampy terrain and quickly erected a temporary camp called Camp Defiance. Floyd ordered the force's tents and cooking utensils sent back to Fort Hull in supply wagons—a decision which upset many of the soldiers.[13]

On January 27, Red Stick warriors made a surprise attack on Camp Defiance in what became known as the Battle of Calebee Creek.[14] After the battle, Floyd remained at Camp Defiance until February 1 treating the wounded and burying the dead.[15] Due to lack of supplies and nearing the end of his soldiers' terms of service Floyd returned to Fort Hull.[16][17][18] Spies that were left at Camp Defiance warned Floyd that the Red Sticks who were still in the surrounding area were planning to attack Fort Hull.[19] Floyd's soldiers were relieved to find seven supply wagons awaiting them at Fort Hull.[18][19] Even with the new supplies, the soldiers grew impatient as their terms of service were ending on February 22. On February 16, Floyd made the decision to march his force back to Fort Mitchell and muster his men out of service.[18]

After Floyd's departure, Colonel Homer V. Milton of the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment was placed in command of Fort Hull.[18][20] Captain John Broadnax from Putnam County, Georgia raised an infantry corps and Lieutenant Fort Adaroin from Franklin County, Georgia raised a rifle corps from the volunteers that remained at the fort. These volunteers were then reinforced by militia from North and South Carolina under the command of Brigadier General Joseph Graham and Thomas Crawford.[8] A US Army company under the command of Captain David E. Twiggs arrived at the fort prior to the North and South Carolina militia.[21] Thomas Simpson Woodward wrote that he was also in command of the fort for a short time.[22] During this time, various raids were conducted on Red Stick camps.[23] While Milton was in command, Fort Hull had a garrison of one hundred to three hundred men, but increased up to six hundred once the fort was better supplied.[24] This force included the Carolina militia, allied Creeks, fifty regular infantry, and four pieces of artillery.[25]

Due to Fort Hull being deep in Creek territory, it was difficult to ensure that supplies would arrive from Fort Mitchell. In March 1814, General Graham constructed Fort Bainbridge on the Federal Road.[26] Fort Bainbridge allowed supply wagons to split the distance between Fort Mitchell and Fort Hull into one-day intervals.[24] After the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, Jackson planned to destroy any remaining Red Stick villages. He planned to gather his forces at Hickory Ground to attack Hoitlewaule with soldiers and supplies from Fort Hull, but this attack was never carried out.[17] Milton then left Fort Hull in March 1814 to construct Fort Decatur further to the west on the Tallapoosa River.[25]

After Milton's departure, only a small number of South Carolina militia remained at Fort Hull. Their terms of service ended in July 1814 after which they returned home. After the militia departed, Fort Hull was under the command of a hospital steward and quartermaster sergeant. Even so, the fort still had a supply of ammunition and rations.[27]

Fort Hull had no military association after 1815 and was soon abandoned.[27][28]

Postwar

Mail was received at a stop known as "Fort Hull" as early as 1818, but there was never a postmaster at the site.[29]

Nearby the fort site was a church and school that were named Fort Hull Church and Fort Hull School.[9]

As late as 1952 a historical marker for the fort was located south of Tuskegee on U.S. Route 80, but no historical marker exists today.[30]

Present

The original site of Fort Hull is unmarked and on private land.[31] The site has been damaged by relic collecting.[32]

References

- ^ Harris 1977, pp. 42.

- ^ a b c Braund, Kathryn. "Creek War of 1813-1814". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ^ a b Blackmon 2014, pp. 31.

- ^ a b Weir 2016, pp. 319.

- ^ O'Brien 2003, pp. 119.

- ^ a b Brannon, Peter A. (April 17, 1932). "Fort Bainbridge, In Russell". The Montgomery Advertiser. Montgomery, Alabama. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ Waselkov & Christopher 2012, pp. 206.

- ^ a b Brannon 1929, pp. 6.

- ^ a b Brannon 1924, pp. 236.

- ^ a b c Weir 2016, pp. 320.

- ^ Jackson 1926, pp. 467.

- ^ Jackson 1926, pp. 457.

- ^ Weir 2016, pp. 321.

- ^ Weir 2016, pp. 324.

- ^ Weir 2016, pp. 330.

- ^ Woodward 1859, pp. 89.

- ^ a b Blackmon 2014, pp. 36.

- ^ a b c d Owsley 2008, pp. 59.

- ^ a b Weir 2016, pp. 331.

- ^ Blackmon 2014, pp. 32.

- ^ Woodward 1859, pp. 90.

- ^ Woodward 1859, pp. 147.

- ^ Waselkov & Christopher 2012, pp. 189.

- ^ a b Owsley 2008, pp. 60.

- ^ a b Waselkov & Christopher 2012, pp. 208.

- ^ Waselkov & Christopher 2012, pp. 222.

- ^ a b Waselkov & Christopher 2012, pp. 209.

- ^ Brannon 1929, pp. 10.

- ^ Brannon, Peter A. (July 12, 1936). "Old Fort Hull Days". The Montgomery Advertiser. Montgomery, Alabama. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ Owen 1952, pp. 268.

- ^ Bunn, Mike; Williams, Clay. "The Canoe Fight". The Creek War and the War of 1812. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ Braund 2012, pp. 250.

Sources

- Blackmon, Richard (2014). The Creek War 1813-1814 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 978-0-16-092542-9.

CMH Pub 74-4

- Brannon, Peter (1929). "Fort Hull of 1814". Arrow Points. 14 (1).

- Brannon, Peter (1924). "Journal of James A. Tait for the Year 1813". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. VIII (3).

- Braund, Kathryn E. Holland (2012). Tohopeka: Rethinking the Creek War & the War of 1812. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-5711-5.

- Harris, W. Stuart (1977). Dead Towns of Alabama. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-1125-4.

- Jackson, Andrew (1926) [Composed 10 October 1813]. Bassett, John Spencer (ed.). Correspondence of Andrew Jackson. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington.

- O'Brien, Sean Michael (2003). In Bitterness and in Tears: Andrew Jackson's Destruction of the Creeks and Seminoles. Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press. ISBN 1-59228-681-X.

- Owen, Marie Bankhead, ed. (1952). "Monuments and Markers". The Alabama Historical Quarterly. 14 (3).

- Owsley, Frank Lawrence Jr. (2008). Struggle for the Gulf Borderlands. Gainesville, Florida: Library Press@UF. ISBN 978-1-947372-34-4.

- Waselkov, Gregory; Christopher, Raven (April 2012). Archaeological Survey of the Old Federal Road in Alabama (Technical report). Montgomery, Alabama: Alabama Department of Transportation.

Submitted by the Center for Archaeological Studies University of South Alabama.

- Weir, Howard (2016). A Paradise of Blood: The Creek War of 1813–14. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme. ISBN 978-1-59416-270-1.

- Woodward, Thomas (1859). Woodward's Reminiscences of the Creek, or Muscogee Indians, Contained in Letters to Friends in Georgia and Alabama. Montgomery, Alabama: Barrett and Wimbish.