Sam Houston was a slaveholder who had a complicated history with the institution of slavery. He was the president of the independent Republic of Texas, which was founded as a slave-holding nation, and governor of Texas after its 1845 annexation to the union as a slave state.[2] He voted various times against the extension of slavery into the Western United States and he did not swear an oath to the Confederate States of America, which marked the end of his political career.

Houston believed that it was more important to stand by other states and their interests than to divide the United States over slavery. He stated that the country was founded on slavery, but when it did not suit the economic needs of Northern states, those states abolished slavery. He claimed that Northern states benefited from slave labor when they bought cotton and sugar produced from Southern plantations. Although he governed Texas as a slave-holding state and was a slave owner himself, he did not feel that it was in the best interests of Texas to secede from the Union over slavery.

Houston and his wife, Margaret Lea Houston, relied on slaves to perform household, agricultural, carpentry, blacksmithing, and other duties for the family. Eliza, who came with Margaret into Houston's family, was critical to running the household and raising the children. She stayed with the daughters of Sam and Margaret until she died in 1898. The multi-skilled Joshua was important to meeting the needs of the family. Houston often hired his servants out for money and allowed them to keep a portion of the money for themselves. When Houston died, Joshua offered to give money to Margaret to help support her children.

Until they were emancipated Houston's servants did not control where and how they were employed. There were limits to how they could spend their free time. They had little power to make decisions for themselves and their children.

Evolution of Houston's attitudes

Early life

Sam Houston was born into a slaveholding family in Virginia.[3][4] His father, Samuel Davidson Houston, an American Revolutionary War veteran, died in 1806 when Houston was eleven. When he was thirteen, his mother Elizabeth Blair Paxton (1757–1831) moved the family of nine children to the wilderness of Blount County, Tennessee. He had little formal education, but read the classics like Caesar's Commentaries (Commentarii de Bello Gallico and Commentarii de Bello Civili), the Iliad, and other books that he could find.[3]

Houston's elder brother placed him in a job at a trading post. He later decided to follow his adventuresome spirit and ran away to a Cherokee village[3] led by Chief John Jolly (Cherokee: Oolooteeskee) on Hiwassee Island.[7] He was welcomed into a community of Native Americans who lived in log cabins. They were farmers and slaveholders, who had a written language. Houston, who wore the clothing of the Cherokees, lived in the village until he was about 18 years of age.[3]

After teaching and completing his education at Porter Academy,[8] Houston fought in the Creek War. He was badly injured but developed what would be a life-long friendship with Andrew Jackson, who was also his political mentor.[9]

President of the Republic of Texas (1836–1838; 1841–1844)

In 1837, a law was passed while Houston was president of the Republic of Texas that outlawed the illegal importation of slaves into the republic[10] and he prohibited slave ships from doing business in Texas. He also refused to allow bounty hunters to receive payments for capturing enslaved people who were on the run[11] and refused to enforce a law that enslaved blacks who lived in Texas for more than two years while free.[12]

U.S. Senator (1846–1859)

Prior to the 1913 Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, United States senators were chosen by their state legislatures, rather than by popular election.[13] Houston served the United States Senate for 13 years, during which he voted against the westward expansion of slavery.[14] He believed that slave labor would not be practical for the types of crops that would be grown in the Western states.[15]

He opposed John C. Calhoun's Address of the Southern Delegates in Congress, to Their Constituents of 1849.[2] A year later, he supported the Compromise of 1850 to promote harmony among the states, which "incurred the permanent wrath of pro-slavery elements".[2] By 1850, Houston was being discussed as a possible candidate for president of the United States, but his marriage to Eliza Allen (his first wife) took him out of the presidential race.[16]

Opposing fellow Southerners, Houston voted against the Kansas–Nebraska Act (1854), which would have spread slavery into western territories and states.[11] It would repeal the Missouri Compromise of 1820 that outlawed slavery north of latitude 36°30'. He warned that passing the act would lead to a civil war.[2][17]

Houston initially had the support of many of his constituents in Texas. As more slaveholders moved into the state,[18] he suffered politically for holding firm to his belief that every state should decide for itself whether it wanted to be a slave state. The only Southern Democrat to vote against the act, the Texas legislature did not reappoint him to the Senate, but allowed him to finish out his term until March 4, 1859.[2] It later earned him a spot, though, in John F. Kennedy's Profiles in Courage.[19] Houston said of his stance: "The glory of my life was that I had the moral manhood on that occasion to stand up against the influences which surrounded me, and to be honest in the worst of times."[20] Houston lost the 1857 Texas gubernatorial election against Hardin Richard Runnels, but defeated Runnels in the 1859 election, becoming the 7th Governor of Texas.[2]

Speech on slavery (1855)

Houston gave a speech on slavery on February 22, 1855, in Boston in which he stated that each of the original states relied on slave labor, although Northern states later outlawed slavery. He felt that each state should determine whether to allow slavery or not.[21]

Houston stated that progress in the United States was due to the supply of low-cost foreign labor, and if low-cost foreign labor could be sustained without the capital investment to purchase black people, slavery would die. He expressed his belief that blacks were better suited to performing long hours of hard work in hot weather in a way that white people could not sustain. Throughout his speech, Houston talked of the need for Northern and Southern states to work together for their individual and mutual interests.[22] The products of slave labor, sugar, and cotton were purchased by Northern states so that there was a mutual dependence on slavery.[21]

He felt that if slaves were to be freed altogether, they would end up living on the streets without jobs, without means to sustain themselves, and the Southern economy would be ruined.[23]

He expressed his opinion about a possible future for slaves in the Colony of Liberia:

There they can rise to the stature of man; there they are prospering and doing well, where there is no opposing race, and they are not trodden down. The slave turned loose here cannot rise to the condition of the white race, and the white race cannot sink to the condition of the black man. Hence the system of transportation to Liberia is the only one that seems to loom up in the distance, by which a provision can be made for restoring these people, at some future day, to the land of their origin.

— Sam Houston[24]

Governor of Texas (1859–1861)

Houston was elected governor when there was growing support for the secession of Texas from the Union.[27] In addition, its white citizens became particularly upset after John Brown raided Harpers Ferry (October 16–18, 1859).[15] It was a key topic of conversation at the time. Slaveholders became more fearful of slave rebellions.[28]

Houston continued to oppose secession. Fearlessly loyal to the United States, he said that he would rather have Texas destroyed than cause disharmony within the Union.[17] He warned that secession would lead to civil war, resulting in a victory by the North and ruination of the South.[29] Houston toured Texas in one last plea to stay with the Union. He said:[30]

... what fields of blood, what scenes of horror, what mighty cities in smoke and ruins – it is brother murdering brother ... I see my beloved South go down in the unequal contest in a sea of blood and smoking ruin.

— Sam Houston, 1860[31]

In San Antonio, at what is now San Pedro Springs Park, Houston spoke against secession in 1860.[32] He narrowly escaped an assassination attempt in Waco, being chased through the streets by an angry mob in late 1860.[30] Throngs of enraged malcontents surrounded the Texas Governor's Mansion in Austin. Around December 1860, Margaret closed the mansion doors to all but those with an invitation from the Houstons.[33]

Houston was the only Southern governor to oppose secession from the Union before the Civil War. On February 1, 1861, a state convention overwhelmingly voted (168 to 8) to secede from the Union. The vote was taken over Houston's opposition.[11][14] The Confederate States of America was established on February 8, 1861, and by March 2, Texas seceded from the Union. On March 16, 1861, Houston refused to swear an oath to the Confederacy.[29] In response, the Texas legislature removed him from office. The pro-Confederacy lieutenant governor Edward Clark assumed his position.[11][14]

Civil War (1861–1865)

About the civil war, Houston stated that he loved Texas too much to support what he was sure would come to it: the death of its citizens and civil strife.[34]

To secede from the Union and set up another government would cause war. If you go to war with the United States, you will never conquer her, as she has the money and the men. If she does not whip you by guns, powder, and steel, she will starve you to death. It will take the flower of the country — the young men.

— Sam Houston[34]

During August 1861, Sam Houston, Jr., enlisted in the Confederate States Army 2nd Texas Infantry Regiment, Company C Bayland Guards, sending Margaret into melancholia.[35][36] Margaret dreaded that her first-born child would never be home again.[36][37] Before Sam Jr. left, his mother gave him a pocket-sized Bible and his father gave him a Confederate uniform.[38]

Houston himself tried to help out by assuming care of their other children in between his extended visits to Galveston.[39] Margaret's fears seemed well-founded when her son was critically wounded and left for dead at the April 1862 Battle of Shiloh. A second bullet was stopped by his Bible, bearing an inside inscription from her. He was found languishing in a field by a Union Army clergyman who picked up the Bible and also found a letter from Margaret in his pocket. Taken prisoner and sent to Camp Douglas in Illinois, he was later released in a prisoner exchange and received a medical discharge in October.[40][41]

Houston's slaves

Houston owned 12 enslaved people[11]

Marriage to Margaret Lea

Before Sam married Margaret, he was the slaveholder of two men named Tom Blue and Esau (also Esaw).[43] Houston, known for having a drinking problem,[44] entered a phase of his life that "worked a complete reformation" of his character, according to Ramage.[45] He married the young Margaret Moffette Lea of Marion, Alabama, on May 9, 1840,[44][45] and he was baptized at the Baptist Church in Independence, Texas, in 1854.[29][45]

Margaret became a slave owner at the age of 14. Her father, Temple Lea, died on January 28, 1834, and in his will, he left her four enslaved people, including Eliza, who was a young girl at the time, and Joshua,[46] who was 12 at the time.[47] Vianna and Charlotte had also been with the Lea family for about as long as Joshua and Eliza.[48][b][c]

Households

Of their many households, the Houstons generally spent the summers in Cedar Point on Trinity Bay. The family lived there in a house built of logs that were weather-boarded. Separate buildings accommodated their servants. In the fall, they resided in Huntsville (at Woodland) or in a house near Baylor College in Independence. Other residences were the Texas Governor's Mansion and Raven Hill.[44][54] Joshua, who was a carpenter, managed the construction of Raven Hill.[55] The estate included the main house and a large kitchen connected to the big house by a covered walkway. There were rows of slave cabins, a smokehouse, barns, and stables. A large vegetable garden provided most of the food for the family and servants.[56] They also had a smokehouse where bacon, sausage, and ham were cured.[57] The family and servants traveled between residences for over a year.[44][54]

Due to her health, Margaret was not able to travel much with Houston. She never visited him in Washington, D.C. when he was a senator and did not accompany him on campaign trails. She created a home environment, with their family of eight children, that he longed to return to.[44]

Events leading up to the 1842 Battle of Salado Creek caused Houston to believe that Mexico was planning a full-scale invasion to re-take Texas. In response, he moved the Republic's capital farther east to Washington-on-the-Brazos[58] and sent Margaret back to her relatives in Alabama. Upon her later return, they temporarily lived with the Lockhart family at Washington-on-the-Brazos until they were able to acquire a small home there.[59] The couple's first child Sam Houston, Jr. was born in the new house on May 25, 1843.[60][61] Upon learning of her son Martin's death in a duel, Nancy Lea moved in with the Houstons, helping Margaret with the new baby, and over Houston's objections, pitching in with some financial assistance for food and household necessities.[62] Nancy received an inheritance from the Moffettes, which she invested in a cotton plantation with 50 slaves. The earnings supported the family while Temple Lea was away from home preaching the Baptist faith.[63]

Houston was concerned for his family's safety during the Civil War. Their former house in Huntsville had been sold, but they were able to rent Steamboat House beginning in 1862.[64] The Houston's lived there with their younger children until Houston died in 1863.[54]

Slave labor

Margaret Lea's parents, Temple and Nancy, had enslaved people who worked their cotton, sugar cane, and vegetable fields from sunrise to sunset. Unlike many slaveholders of the time, the Leas did not believe in corporal punishment, like whipping.[66][d] Their diet probably consisted of bread, cornmeal, pieces of meat, and greens.[66]

When women were too old to work in the fields, they took care of children in the nursery. Black children spent their first couple of years in the nursery.[66] At the age of five, children took on chores like tending to animals, maintaining the yard, and gathering water, cow's milk, and firewood. At the age of ten, children were laborers in the fields or apprenticed into trades.[66] At harvest, laborers worked 18-hour-days in the fields. Boiling down sugar cane could occur seven days a week, 24-hours a day.[69] The Leas observed the Sabbath. Sunday was not a work-day, except for the most necessary chores. Nancy Lea often invited slaves to Bible readings. Temple was a Baptist lay minister.[65] In their little leisure time, they engaged in story-telling, their domestic chores, fishing, hunting, and trapping.[65]

On plantations, the more skills that a slave possessed, the more valuable he was to his slaveholders, and consequently he received the best treatment.[70] Among African Americans, they looked up to black people who attained skills or were domestic workers; black preachers, who generally provided services in the woods; and those who successfully escaped to Canada, Mexico, or Native American villages.[65]

In November 1848, slaves at Houstons' household were assigned a plot of land to raise crops for themselves.[71] Their children were educated with the Houston's children.[72] Joshua traveled with Houston on multiple-day trips across Texas. Both men carried rifles for protection and hunting games. Joshua was responsible for ensuring that the horses were cared for if injured or ill and that any equipment was in working order, requiring him to take tools with him. They traveled through dense forests on unimproved trails, roads, and river beds. They visited people that Houston knew across the state, which allowed Joshua to meet and exchange information with other enslaved people.[73] When Margaret traveled with them in the early years of their marriage, they took a tent and a doctor to care for Margaret's health.[74]

In 1848, when Eliza was bed-ridden with scrofula and Margaret was trying to manage household affairs, several field hands were unable to keep up with the expected workload on the farm. In a letter, Houston asked Margaret to warn the field hands that he would be returning to the estate any day and that they should rely on their sense of pride to do a good job. He said to Margaret, "I will make them more careful and industrious."[75] While Thomas Gott was the farm's new overseer, Margaret became concerned about his lax management style. She was concerned with how much meat that they received, that they received visitors and went into town in the evenings. She was also concerned about gambling and drinking.[76] Once he tried to whip Joshua, who fought off receiving the punishment.[71]

Houston did not whip his slaves generally, but he whipped Jeff one time when Houston's horse "Old Pete" had reared up and Houston's daughter Nannie was thrown into the baptismal pond in Huntsville. Jeff, who was supposed to be watching out for Nannie, rescued her from the water. Nannie had earlier told Jeff to hit the vicious horse with a switch, which he did not do.[77]

Hired out

At times, Houston hired workers out for income for the family. He was one of the rare slaveholders that allowed the men and women to keep a portion of the wages for themselves.[78][79] In 1851, Prince and a woman named Mary were hired out for one year to Daniel B. Guerrant and John McAdams. During that time Mary's children were cared for and Prince, Mary, and Mary's children received clothing.[80] In 1854, Bingley was hired out and learned the carpentry trade, Jeff was hired out as a house boy, and Prince was hired out for $175 (equivalent to $5,934 in 2023) and clothing.[81] Joshua was hired out as a blacksmith and received a portion of the earnings, much of which he saved.[10][11] He occasionally hired out farm laborers and left house servants at Houston's residence.[82]

There were a couple of slaves who instigated discord within the household. Houston sometimes hired them out to create peace among the enslaved people.[83] Of African and European descent, Charlotte lived at Cedar Point,[84] until she was sold to another planter, due to the trouble that she made among the other slaves.[85] She constantly fought with Eliza.[86] Most slaveholders kept all of the wages that were earned when their slaves were hired out. Houston let his bonds people keep a portion of the wages.[83] At some point, Houston entered an arrangement with his Raven Hill overseer, Captain Frank Hatch. Instead of paying him in cash, Houston provided field hands to work Hatch's farm at Bermuda Spring.[87] Later, Hatch and Houston exchanged properties, with Houston taking ownership of Bermuda Spring.[88]

Slave laws and lack of liberty

The laws of Texas restricted what slaves could do. Unless they were with their slaveholders, they could not gather with three or more people.[89] Any time that blacks met, including at worship services, it was assumed that they were planning escapes.[38] They could not gamble, buy liquor, sell goods without their owner's permission, and they could not own and carry weapons.[89] Like Joshua, Houston's slaves were unable to marry, educate their children, purchase property, and testify in court. They were subject to abuse by others when they left the Houston property.[90] Their greatest fear was being kidnapped and sold to an unknown place.[89] Vigilante committees scoured the streets looking for blacks unaccompanied by their owners.[90] Traveling alone could result in being captured, imprisoned, or lynched.[91]

Emancipation

According to a legend, Houston told his slaves that they were free after reading the Emancipation Proclamation (September 22, 1862) to them.[11] The proclamation took effect on January 1, 1863. However, slaves in Texas were not emancipated until June 19, 1865, by the issuance in Galveston of General Order No. 3 from Union General Gordon Granger, almost two years after Houston's death. The Texas constitution in effect under the Confederacy, Section III, Article 2, prohibited manumission (a slave owner freeing his slaves). Additionally, Section I made it illegal for state laws to be enacted that would emancipate slaves.[92][93][94][95][96][97] Therefore, the Houstons could not legally manumit their slaves.[93][98] Joshua stated that he would stay with the family, and others followed suit. Due to the war and animus against blacks, they were safer together with the Houstons.[99]

| Name | Age | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Joshua | 35 | $2,000 |

| Eliza | 32 | $800 |

| Pearl | 25 | $1,200 |

| Nash | 22 | $1,200 |

| Dolly | 17 | $800 |

| Lizzie | 25 | $800 |

| Solomon | 6 | $900 |

| Lotte | 4 | $400 |

| Jeff | 13 | $700 |

| Jack | 23 | $1,000 |

| Lewis | 55 | $400 |

| Mariah | 50 | $400 |

When Houston died, his will specifically directed his debts to be paid without selling any of the slaves. Author James L. Haley speculated that listing his slaves as part of his estate, was a way of protecting them from abuse by the Confederacy, should emancipation come to fruition in Texas.[102] The provision in his will also refutes popular lore that he intended to free his slaves. He was cash poor, but land rich,[103] including owning twelve enslaved people.[11] The inventory compiled of his estate after his death listed several thousand acres in real estate, $250 cash, slaves, a handful of livestock, and his possessions. Margaret and the other executors of his estate specifically named each of the 12 slaves on the inventory, with a total valuation of $10,530 (equivalent to $260,575 in 2023).[103][e] Three slaves who worked for Houstons were not listed on the inventory of his estate when he died. Bingley was legally Nancy's slave inherited from her deceased husband, but worked with the other Houston slaves after Margaret and Sam married. It is not known what happened to Albert and Prince.

Haley states that Margaret tried her best to keep their slaves with the family.[102] Prather stated that Margaret let most of the slaves go; Eliza and Bingley wanted to stay with her and they moved with the family to Independence.[104] Margaret died on December 3, 1867, of yellow fever.[29] Houston's slaves were officially freed on Juneteenth in 1865.[105]

Biographies of slaves owned by Sam and Margaret

Albert

Albert was a servant for the Houstons. In June 1848, Margaret wrote to Houston that Albert "was so cunning that he was very near getting into the church but fortunately his hypocrisy was discovered and I fear he is planning some great act of villainy."[106] There was no work for him at their house until fodder time. Doctor Kittrell hired Albert at $20 (~$732.00 in 2023) per month in June 1852.[107] Joshua Houston and Albert maintained contact with each other until the turn of the 20th century.[108] Albert and Prince led the parade at Juneteenth celebrations, dressed "in their best frocks and top hats".[109]

Bingley

Bingley was an enslaved man owned by Temple Lea. Upon the death of Temple Lea, Bingley was inherited by Temple's widow Nancy. He went with her to Galveston, Texas, along with Polly, Jet, and Dinan. Being African Americans, they would have had to register at the Mayor's office. Galveston was a major slave market and it was common for blacks to be picked up off the street and sold at an auction. Nancy moved to Texas around the time that Margaret and Houston were married in Marion, Alabama, on May 9, 1840.[110] Bingley was later a servant to Margaret. He worked as a field hand with Joshua, Albert, and Prince.[111] In 1854, he was hired out and learned the carpentry trade.[81] Following Houston's death, Bingley decided to stay with Margaret, as did Eliza.[104] He was with her when she died of yellow fever in Independence. He buried her promptly in the middle of the night next to her mother Nancy.[112]

Charlotte

Charlotte had been owned by Temple and Nancy Lea and was born about the same year as Joshua.[43] She was one of the women, along with Vianna, whose work was managed by Eliza. Charlotte had a bad temper, which got out of hand at times.[43] In late 1849, Margaret decided to sell Charlotte, who had become too disruptive.[113] She was sold for $500 to Colonel James Gillespie,[72][114] who was aware of her temperament and thought that he could control her.[114]

Eliza Revel

Eliza was purchased from an auction block in Mobile, Alabama. Margaret had accompanied her father on a trip and as they passed the village square, she saw a black girl that seemed to be about her age. She begged her father Temple Lea to buy the girl.[46] Eliza said that she lived on a plantation in the Tidewater area of Virginia and was lured away by a friendly white man who offered Eliza and her friends a ride in his buggy.[48][f] She went with them, was placed on the auction block, and was purchased by Temple Lea.[46]

"Aunt" Eliza Revel was Margaret's close companion and body servant.[115][116] She managed five domestic servants and she was the main cook.[44][116][117] Margaret's mother, Nancy Lea, often lived with the family until 1853. Eliza and Nancy managed most of the household affairs. Margaret, who was not interested in mundane tasks,[44][117] relied on Eliza, particularly when she was not well or during her pregnancies.[116] Eliza had a collection of herbal medicines that she used to care for the family.[118][g] Eliza helped raise Margaret's children and some of her grandchildren.[46]

Aunt Eliza could not be more devoted to your interest if you were her own child… Often I think of a remark which dear Wes made about her—that 'she was an example to all of us'. She never forgets the comfort or fancies of any one and is a mother to everything on the place.

— The Houston's daughter, Nannie[121]

In the summer of 1848, Eliza became quite ill with scrofula, which concerned Margaret and Sam and disrupted the management of the household.[122] At some point, she went to the mineral springs of Sour Lake, Texas, which helped her recover.[98] Eliza never learned how to read or write. Valued for her many skills, a sugar plantation owner offered Margaret $2,000 (equivalent to $73,248 in 2023) to purchase Eliza, which was rejected.[79]

After Margaret's death, Eliza helped her daughters Maggie in Independence and Nannie in Georgetown raise the youngest of Margaret's children.[123] Eliza died at Maggie's house in Houston on March 9, 1898.[121] As requested, she was buried just a few feet away from Margaret at the family plot in Independence.[105][121][124] Her headstone reads, Aunt "Eliza Faithful unto Death".[124]

Jeff Hamilton

Jeff Hamilton was born a slave on April 16, 1840, on the Singleton Gibson Plantation in the Jones community of Shelby County, Kentucky.[125][126] Mary Brown Gibson moved to Fort Bend, Texas, with her husband, who was killed. She married a drinker and gambler named James McKell.[126] McKell put Jeff up for sale in October 1853 in Huntsville.[125][126] His owner sold him so that he could pay a debt for two barrels of whiskey.[10] Houston, having taken a trip into town, saw Jeff crying on the auction block while he was being teased by white children. Although he did not need more slaves, Houston saw the boy's distress; he appeared tired, hot, and thirsty.[127] Houston paid $450 for Jeff under the stipulation that he could buy his mother and siblings, which was ignored. Jeff did not see his mother again for 25 years.[10]

Jeff was accustomed to a diet of cornbread and hoecakes, but his first meal at the Houstons included pork, sweet potatoes, cracklin' bread, and tripe. The boy was brought to Joshua's cabin, where he slept. He fed the farm animals, including cows and pigs. He was also responsible for tending to the hopper of fireplace ashes, which was wetted down by rain and generated lye, which was used to make soap.[128] He had a close relationship with the family. He played with the Houston children and sat in on family lessons about religion and responsibility. He learned reading, writing, and arithmetic.[125]

He later worked for the Houstons as a bodyguard, valet, and driver.[125] When Houston went back on the campaign trail, which included 67 speaking engagements, he took Jeff with him. They occasionally slept under the stars on blankets.[130] When Houston became governor in 1859, Jeff was his office boy.[125] Houston became seriously ill in 1863 and Joshua drove him to the mineral springs in Sour Lake, Texas.[131] Jeff was also said to have looked after him at the spa. Without any improvement in Houston's condition, they returned to the Steamboat House in Huntsville. Houston died on July 26, 1863.[129]

Jeff stayed with the family until Margaret Houston's death. From 1889 to 1903, he worked at Baylor College as a janitor. When the female college moved to Belton, Hamilton moved there, too. It is now Mary Hardin-Baylor University, where a historical marker honors Jeff. Jeff died in 1941. There is also a historical marker at his gravesite.[125] He asked to be buried at Houston's feet.[105]

In his memoir My Master – The Inside Story of Sam Houston and His Times, Hamilton said that he could not have imagined that Houston would "make him the trusted servant of a great leader, one who believed in the just and humane treatment of my people."[10]

Joshua Houston

Joshua Houston was born a slave in 1822, likely in the home of Temple Lea, Margaret's father, in Marion, Alabama. Temple died in 1834 and left Joshua to his daughter Margaret.[132] At twelve years of age, Joshua worked as hard as grown men, working from the break of day until sunset in the vegetable, cotton, and sugar cane fields. He tended to the animals and performed chores.[47] He was apprenticed out for several trades.[47] Joshua had a relationship with Anneliza, and they had a son Joe in 1836 and in Texas, he fathered more children with Anneliza, Margaret Green, and Sylvester.[132]

He was a coachman, blacksmith, carpenter, wheelwright, gardener, and architect.[11] Joshua was enslaved by Temple Lea. He came with Margaret upon her marriage to Sam Houston. He became a trusted servant, devoted to both Margaret and Sam Houston.[51] He also managed the farm when Houston was away.[63] In 1845, Joshua managed and performed construction on Raven Hill, a family house in the countryside,[55] 11 miles (18 km) from Huntsville.[133]

When Houston died, the family was land rich and cash poor.[134] Joshua visited Margaret Lea Houston and her eight children in Independence, Texas. He arrived with two thousand dollars (equivalent to $45,780 in 2023) for her that he had saved up.[h] She refused the offer, stating that the money should go towards the education of his children.[11] Joshua visited the Houstons from time-to-time to help her.[135]

Joshua worked as a blacksmith. During the Reconstruction era, Joshua was a county commissioner, city councilman, founder of a college, and trustee of three churches. He was the subject of the book From Slave to Statesman, by Pat Prather and Jane Monday.[11] He did give his children a good education. One of his sons became the president of Sam Houston Manual Training School. After he died, he was interred in the Huntsville cemetery near Sam Houston.[135]

Mary

Mary was hired out in 1851 by Daniel B. Guerrant or John McAdams. Her children went with her and were cared for while Mary worked. Mary and her children received clothing as part of the agreement.[80] In 1848, two weeks after Nancy Lea's servant Vianna died of pneumonia, Mary was believed to have been consumptive, which concerned Margaret. A doctor was called in to care for her.[136] Mary and Eliza joined the Baptist Church in Huntsville. The servants sat in a balcony above the white congregation.[137]

Prince

In 1848, it is believed that Prince and Joshua built the wooden coffin for Vianna, who had been with the Lea family for almost 20 years.[138] That year, Prince was one of three field hands, along with Bingley and Joshua. Due to having just a few laborers, Margaret did not expect a good crop that year. All but thirteen sheep and three goats had scattered and were lost. They harvested the spring crops over a while and began planting vegetables for the summer, which was completed on July 4.[139] In 1851, Prince and a woman named Mary were hired out for one year to Daniel B. Guerrant and John McAdams. The family would receive $200 and Prince and Mary were outfitted with summer and winter clothing, including shoes. Mary’s children were to be cared for and given clothing as well. If they were still alive at the end of the contract, they were to be returned to the Houstons.[80] Prince, Houston's foreman by 1853, tended to the farm animals.[57]

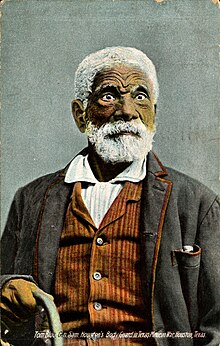

Tom Blue

Tom Blue was of West Indian and European descent. He was said to have had a good education and went with Houston to Washington, D.C. When he was in Texas, he drove Margaret in Houston's big yellow coach.[93]

Tom and Esau

Houston was Tom's and Esau's slaveholder before he married Margaret.[43] Esau was known for his ability to mix drinks for Houston, something he did often until Houston's 1840 marriage to Margaret Lea.[141] With Joshua, the men turned Houston's bachelor cabin in Cedar Point to a home befitting the newlyweds, Sam and Margaret Houston.[43]

According to William Seale, Esau was at work on the farm at Cedar Point in the summer of 1840 with Margaret. Houston decided to hire out some of the men as the result of infighting. Tom and Esau went missing during that time and ended up in Mexico.[4][142] In September 1840, Sam wrote to Margaret that Tom and Esau had been found in the town of Houston.[143] Esau was with Sam and Margaret in 1842.[144]

Noah Smithwick states that Tom was a light "Quadroon boy" who worked in Houston's office. Tom was described as literate with a sophisticated vocabulary. Smithwick states that there was another black man-servant named Shadwick (perhaps Esau Shadwick). He stated that Tom ran away with Shadwick, taking two of Houston's horses and money from his office till. Tom portrayed himself as Mr. Thomas Houston, Houston's son, and Shadwick's master.[145]

On January 8, 1843, General Ampudia marched into Guadaloupe, a town about 5 miles (8.0 km) from Matamoros. There he met with people from Matamoros, including Esau and Tom, who were identified as former slaves of Sam Houston. When Esau met General Ampudia, they embraced like good friends. Esau, suited to be a field hand, was generally introverted. Tom was more comfortable engaging with the Texans.[146]

In May 1844, a newspaper item stated that two of Sam Houston's slaves, Tom and Esau, ran away and were both were working in Matamoros as barbers. The men were said to previously have been sources of information about the workings of the Texan government when they worked for Houston.[147] Esau is said to have become a hotelier in Matamoros.[4]

In the fall of 1862, Blue ran away from Houston's Huntsville residence with a young black boy named Walter Hume. They headed for Mexico and Blue sold Walter for $800. When he had spent all the money, he returned to Texas. At the end of his life, he was reportedly a beggar on the streets of Houston.[93]

See also

Notes

- ^ The reconstructed Cherokee farm house is one of the structures at the Red Clay State Historic Park in Bradley County, Tennessee.[5]

- ^ Margaret brought four enslaved people with her to the marriage: Vianna; two girls, Charlotte and Eliza; and a boy named Jackson, who was later traded to Nancy Lea for Frankey, a field hand.[45][49] Eliza traveled with Margaret to Texas. The three others traveled with Margaret's brother Martin.[50] Roberts said that Margaret arrived in Texas with a young man named Joshua, a trusted long-term servant, and Eliza.[51]

- ^ Nancy Lea, Margaret's mother, moved to Texas around the time of Margaret's and Sam's marriage. Accompanying her were enslaved servants Bingley, Jet, Polly, and Dinan.[52]

- ^ Some slaveholders felt that they "had to beat somebody every day." Randolph Campbell, author of An Empire for Slavery: the peculiar institution in Texas, 1821–1865 stated that "Slaves were whipped for many reasons, including running away, stealing, fighting, insolence, and failure to complete their work on time and to their masters' satisfaction."[67] According to the Texas penal code of 1860, whippings and death were the only punishments for slaves. In one case, a slave was to receive 750 lashes of the whip, but Houston, governor at the time, pardoned him to stop the punishment.[68]

- ^ a b The interpretation of the names and amounts are best guesses. The actual names and amounts may vary. This list totals $10,600. It is not clear how the total of $10,530 was derived.

- ^ Roberts states that Eliza did not know her age, her family name, or where she was from. She had been tricked by some slave catchers to come with them from outside her mother's cabin.[46] Judy Routh of the Sam Houston Memorial Museum states that she was born free and was enslaved at four years of age.[105]

- ^ When Margaret was ill with a bad cough that she thought might be consumption, she became afraid that she would not survive the illness and the birth of her fourth child. She asked Eliza to promise that if she should die, Eliza would raise her children.[119] After Margaret delivered the baby, a daughter they named Mary William Houston, she remained shut in her bedroom for five weeks, cared for by Eliza who was "kind and faithful".[120]

- ^ a b Joshua Houston was said to have accumulated life savings of $175,000 (equivalent to $4,005,750 in 2023) in gold in the 1860s, including money that he made working as a blacksmith while enslaved.[10][11]

References

- ^ "Portrait of Sam Houston". Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

- ^ a b c d e f Kreneck, Thomas H. "Houston, Sam". Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ^ a b c d Ramage 1894, pp. 310–311.

- ^ a b c Williams 2018, p. PT207.

- ^ Shelton, S. Danielle (February 2019). "Red Clay State Park Cultural Landscape Inventory & Assessment" (PDF). MTSU Center for Historic Preservation. Middle Tennessee State University. p. 30. Retrieved 2021-01-09.

- ^ Gregory 1996, pp. 10–11.

- ^ "History of Hiwassee Island" (PDF). The Center for Historic Preservation, Middle Tennessee State University. April 2019. Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ Haley 2004, p. 7.

- ^ Ramage 1894, p. 312.

- ^ a b c d e f g Russell, George H. (2021-06-18). "Sam Houston despised slavery". Associated Press. Retrieved 2021-07-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Krystyniak, Frank. "Houston, the Emancipator – Today@Sam – Sam Houston State University". Sam Houston State University. Retrieved 2021-07-10.

- ^ "Sam Houston: A Study in Leadership" (PDF). Constitutional Rights Foundation. p. 2. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ "Senators". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- ^ a b c Klein, Christopher. "7 Things You May Not Know About Sam Houston". HISTORY. Retrieved 2021-07-10.

- ^ a b "Sam Houston: A Study in Leadership" (PDF). Constitutional Rights Foundation. pp. 2–3. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ Krystyniak, Frank. "Sam Houston Biography: Presidential Ambitions". Sam Houston State University. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- ^ a b Maher 1952, p. 449.

- ^ Ramage 1894, p. 320.

- ^ "Summary of Sam Houston (Chapter V) from Profiles in Courage by John F. Kennedy". U.S. Senate. Retrieved 2021-07-10.

- ^ Maher 1952, p. 448.

- ^ a b Houston 1943, pp. 167–171.

- ^ Houston 1943, pp. 175–177.

- ^ "Sam Houston: A Study in Leadership" (PDF). Constitutional Rights Foundation. pp. 2–3. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ Houston 1943, p. 172.

- ^ "Treasured Artworks at the Texas Capitol: Portraits". Traditional Fine Arts Organization. Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ "Painting of Sam Houston, by William Henry Huddle, in the House of Representatives chamber in the Texas Capitol in Austin, Texas". Library Of Congress Public Domain Search. Library Of Congress. 2014-01-01. Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ Ramage 1894, p. 321.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d "Sam Houston". Texas State Library and Archives Commission. 2015-03-19. Retrieved 2021-07-14.

- ^ a b Ryan, Terri Jo. "Brazos Past: Sam Houston's visit to Waco". WacoTrib.com. Retrieved 2021-07-12.

- ^ Haley 1993, p. 328.

- ^ Huddleston, Scott (2019-12-08). "San Pedro Springs Park, with a rich, colorful history and ties to San Antonio's beginnings, will get an extensive overhaul in 2020". San Antonio Express News. Retrieved 2022-01-02.

- ^ Haley 2006, p. 292.

- ^ a b "Quotes by Sam Houston". Sam Houston State University. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ Houston & Roberts 1996d, p. 387.

- ^ a b Seale 1992, pp. 213–215.

- ^ Houston & Roberts 1996d, pp. 394–395.

- ^ a b Prather 1993, p. 68.

- ^ Seale 1992, pp. 218–221.

- ^ Haley 2004, pp. 402–404.

- ^ Roberts 1993, pp. 313–314, 318.

- ^ "Margaret Lea Houston". Sam Houston State University Library. Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ a b c d e Prather 1993, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g Seale, William. "Houston, Margaret Moffette Lea". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ^ a b c d Ramage 1894, pp. 320–321.

- ^ a b c d e Roberts 1993, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Prather 1993, p. 2.

- ^ a b Prather 1993, p. 10.

- ^ Seale 1992, pp. 17, 40.

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 32.

- ^ a b Roberts 1993, p. 38.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 9.

- ^ "Woodland, Huntsville, Texas". National Parks Gallery, National Park Service. Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ a b c "History of Margaret Lea (timeline)". Sam Houston State University. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ a b Roberts 1993, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Roberts 1993, p. 141.

- ^ a b Prather 1993, p. 48.

- ^ "The Capitals of Texas". Texas Almanac. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- ^ Seale 1992, pp. 70–72, 75.

- ^ Roberts 1993, p. 99.

- ^ Seale 1992, pp. 83–86.

- ^ Houston & Roberts 1996a, p. 286.

- ^ a b Seale 1992, p. 109.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 70.

- ^ a b c d Prather 1993, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d Prather 1993, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Campbell 1989, p. 146.

- ^ Campbell 1989, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 3.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 4.

- ^ a b Prather 1993, p. 40.

- ^ a b Prather 1993, p. 43.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 14.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 16.

- ^ Roberts 1993, p. 173.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 39.

- ^ Prather 1993, pp. 49, 72.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 15.

- ^ a b Seale 1992, p. 55.

- ^ a b c Prather 1993, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Prather 1993, p. 50.

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 132.

- ^ a b Seale 1992, p. 15.

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 40.

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 128.

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 45.

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 121.

- ^ Seale 1992, pp. 122–123.

- ^ a b c Prather 1993, p. 13.

- ^ a b Prather 1993, p. 66.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 74.

- ^ "Constitution of Texas:Article VIII: Slaves". Tarlton Law Library. Retrieved 2021-07-14.

- ^ a b c d Roberts 1993, p. 319.

- ^ Campbell, Randolph B. (July 1984). "The End of Slavery in Texas: A Research Note". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 88. The Portal to Texas History: 71–80.

- ^ "Juneteenth". Texas State Library and Archives Commission. Retrieved 2016-03-18.;"Article VIII, Section 2". Texas Constitution amended 1861. Tarlton Law Library. Retrieved 2016-03-18.

- ^ Porterfield, Bill (July 1973). "Sam Houston, Warts and All". Texas Monthly. 1 (6): 67.

- ^ Cox, Mike. "Sam's Will". Texas Escapes. Blueprints For Travel, LLC. Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- ^ a b Prather 1993, p. 71.

- ^ Prather 1993, pp. 70–71.

- ^ "Inventory of Sam Houston's Estate". digital.library.shsu.edu. Retrieved 2021-07-23.

- ^ "Sam Houston, Warts and All". Texas Monthly. 1973-07-01. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ^ a b Haley 2004, p. 418.

- ^ a b Haley 2004, p. 417.

- ^ a b Prather 1993, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b c d Wulfson, Michelle (2021-02-09). "Telling the complete history of Sam Houston". The Item. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ Prather 1993, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Prather 1993, pp. 39, 46.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 186.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 175.

- ^ Prather 1993, pp. 9–10, 25.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 37, 46.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 102.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 42.

- ^ a b Houston 1996c, p. 147.

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Weaver, Briana. "Woodland Home Kitchen". East Texas History, Sam Houston State University. Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ^ a b Seale 1992, pp. 40, 55.

- ^ Seale 1992, p. 65.

- ^ Roberts 1993, p. 197.

- ^ Roberts 1993, p. 205.

- ^ a b c Roberts 1993, p. 358.

- ^ Roberts 1993, pp. 170–173, 177.

- ^ Roberts 1993, p. 357.

- ^ a b Haley, James L. (2015-04-10). Sam Houston. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-8061-5215-8.

- ^ a b c d e f "A Guide to the Jeff Hamilton Interview, 1938". legacy.lib.utexas.edu. Retrieved 2021-07-12.

- ^ a b c "Hamilton, Jeff · Notable Kentucky African Americans Database". nkaa.uky.edu. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ^ Roberts 1993, p. 263.

- ^ Prather 1993, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b Roberts 1993, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Roberts 1993, pp. 263–264.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 72.

- ^ a b Prather 1993, pp. xv–xvii.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. xv.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. Prologue.

- ^ a b Roberts 1993, p. 336.

- ^ Prather 1993, pp. 37, 39.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 51.

- ^ Prather 1993, p. 37.

- ^ Prather 1993, pp. 37–38.

- ^ "Tom Blue, General Sam Houston's bodyguard". University of Houston Libraries Special Collections. Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ^ Williams 2018, p. PT197.

- ^ McCutchan 2014, p. 67.

- ^ Roberts 1996, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Roberts 1996, pp. 235, 238n.

- ^ McCutchan 2014, p. 68.

- ^ McCutchan 2014, pp. 67–68.

- ^ "Fugitive slaves – Tom and Esau, two of General Houston's men". The Weekly Despatch. 1844-05-11. Retrieved 2021-07-13 – via digital.sfasu.edu.

Bibliography

- Campbell, Randolph B. (1989). An empire for slavery : the peculiar institution in Texas, 1821–1865. Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-1505-3.

- Gregory, Jack Dwain (1996). Sam Houston with the Cherokees, 1829–1833. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-8061-2809-2.

- Haley, James L. (1993). Texas: From Spindletop Through World War II. St. Martin's Press.

- Haley, James L. (2004). Sam Houston. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3644-8.

- Haley, James L. (2006). Passionate Nation: The Epic History of Texas. New York, New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-684-86291-0.

- Houston, Sam (1943). "Extracts from a Speech on Slavery, Tremont Temple, Boston on February 22, 1855". The writings of Sam Houston, 1813–1863. Austin, Texas. pp. 167–171. hdl:2027/uva.x030132331.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Houston, Sam; Roberts, Madge Thornall (1996a). The Personal Correspondence of Sam Houston – Vol. 1: 1839–1845. University of North Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-57441-000-6.

- Houston, Sam (1996c). The Personal Correspondence of Sam Houston: 1848-1852. University of North Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-57441-063-1.

- Houston, Sam; Roberts, Madge Thornall (1996d). The Personal Correspondence of Sam Houston – Vol. 4: 1852–1863. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-57441-084-6.

- Maher, Edward R. (1952). "Sam Houston and Secession". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 55 (4): 448–458. ISSN 0038-478X. JSTOR 30237605.

- McCutchan, Joseph D. (2014-03-01). Mier Expedition Diary: A Texan Prisoner's Account. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-78091-0.

- Ramage, B. J. (1894). "Sam Houston and Texan Independence". The Sewanee Review. 2 (3): 309–321. ISSN 0037-3052. JSTOR 27527811.

- Prather, Patricia Smith (1993). From slave to statesman : the legacy of Joshua Houston, servant to Sam Houston. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-929398-47-1.

- Roberts, Madge Thornall (1993). Star of Destiny: The Private Life of Sam and Margaret Houston. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas Libraries. Retrieved July 11, 2021 – via The Portal to Texas History.

- Roberts, Madge Thornall (1996). The Personal Correspondence of Sam Houston, Volume 1: 1839–1845. pp. 18–20.

- Seale, William (1992) [1970]. Sam Houston's Wife: A Biography of Margaret Lea Houston. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8061-2436-0.

- Williams, John (2018). Sam Houston. New Word City. ISBN 978-1-64019-148-8.

Further reading

- Hamilton, Jeff; Hunt, Lenoir (1992). My Master: The Inside Story of Sam Houston and His Times. State House Press. ISBN 978-0-938349-84-6.

- "Speech of Hon. Sam Houston, of Texas, on the subject of Compromise of 1850. In the Senate of the United States, February 8, 1850". Hathi Trust. 1850.

External links

- The Sam Houston Memorial Museum located in Walker County's City of Huntsville curates exhibits that highlight the lives of General Sam Houston's enslaved workforce. The grounds of the institution also features some of the land the enslaved persons worked.

- "Plays depict slave life in Houston household". www.shsu.edu.