Contents

Natural disasters in Nigeria are mainly related to the climate of Nigeria, which has been reported to cause loss of lives and properties.[1] A natural disaster might be caused by flooding, landslides, and insect infestation, among others.[2] To be classified as a disaster, there is needs to be a profound environmental effect or human loss which must lead to financial loss.[3] This occurrence has become an issue of concern, threatening large populations living in diverse environments in recent years.[4][5][6]

Nigeria has encountered several forms of disaster, which range from flooding, soil and coastal erosion, landslides, tidal waves, coastal erosion, sand-storms, oil spillage, locust/insect infestations, and other man-made disasters.[7][8] It can be said that the country's under protected and expansive environment contributed to making the people especially vulnerable to these disasters. Other dangers include northern dust storms, which is usually from northern states to southern, causing damages through large deposits of dust and dirt from these regions. Hail is another cause, which rarely occurs in parts of Nigeria, leading to damage of crops and properties.[9][10]

Types

Drought and Desertification

Drought

Drought stands as a significant contributor to desertification. The absence of a universally accepted, precise, and objective definition for drought has posed a substantial challenge in studying this phenomenon. It's crucial to recognize that differing definitions can yield distinct conclusions concerning drought. For instance, if the definition relies on rainfall levels, it's conceivable that when summarizing rainfall statistics over a calendar year, no drought may be apparent, even though moisture supply during the growing season may indicate otherwise. In the context of food security, drought can be defined as a naturally occurring phenomenon, often exacerbated by human activities, which persists over a specific period in a particular region, leading to a substantial drop in precipitation levels, resulting in land degradation and significantly reduced agricultural yields. However, it's important to emphasize that due to drought's multifaceted impact on various societal sectors, the need for multiple definitions exists.[11] Factors such as the specific problem being investigated, data availability, and climatic and regional characteristics play a role in determining the appropriate definition for an event.

Research characterized drought as a situation marked by insufficient water availability.[12] Many researchers offer context-specific definitions of drought. Another author described drought as prolonged deficiencies in both surface and sub-surface water, which disrupt the normal functioning of natural ecosystems.[13] Notably, these definitions did not emphasize the shortage of precipitation, moisture content, or water demand; instead, they focused on deficits in surface water (such as streamflow) and groundwater. It is this sustained insufficiency of water that leads to drought. The primary factor responsible for drought is inadequate precipitation, with the severity influenced by factors like timing, distribution, and the intensity of rainfall.[13]

In recent years, droughts have resulted in a greater number of environmental refugees than any other period in human history and have caused more deaths than any other natural disaster in the latter half of the 20th century.[14]

Socio-economic activities and environmental degradation can occur concurrently. For instance, over-exploitation of natural resources may be a coping strategy in response to extreme climate events.[15] Drought has profoundly impacted the social lives of farmers in semi-arid Bangladesh, where farmers perceive an increase in drought frequency due to climate change.[16] However, the perception of climate change among rural farmers is influenced by factors such as their level of education, means of livelihood, and geographic location.[17]

Drought can be categorized and defined using several criteria, including meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, and socio-economic aspects.

- Meteorological Drought: This type of drought occurs when the level of precipitation falls below the long-term normal recorded levels. It is primarily related to deviations from expected rainfall patterns.

- Agricultural Drought: Agricultural drought arises when the soil moisture content is insufficient to satisfy the requirements of crops during a specific period. This directly impacts agricultural productivity.

- Hydrological Drought: Hydrological drought is characterized by a shortage of water supply due to the reduction or absence of both surface and subsurface water sources. It pertains to imbalances in the availability of water resources.

- Socio-economic Drought: This form of drought is linked to human activities and occurs when various human endeavors are hindered due to reduced precipitation or water availability. It has social and economic implications.

In essence, drought typically results from inadequate seasonal precipitation, an extended dry season, or a sequence of below-average rainy periods.[18] The defining feature of drought is a substantial reduction in water availability within a particular timeframe and geographic area. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) (1994) characterizes drought as a naturally occurring phenomenon that emerges when precipitation significantly falls below the recorded normal levels, causing significant hydrological imbalances that adversely impact land resource systems. Continued land mismanagement during drought exacerbates land degradation. Insufficient rainfall and prolonged periods of low water flow can have severe consequences for water management and utilization, affecting various aspects such as river pollution, ecological considerations, reservoir planning and operation, irrigation, small-scale power generation, and drinking water supply. The demand for water is particularly critical during severe and widespread drought episodes in the future.[19]

Impact of drought in Nigeria

Drought has been a persistent issue in West Africa for numerous decades, but it didn't garner significant attention until the occurrence of the severe Sahelian droughts during the 1970s.[20] In recent years, the documentation of drought has been inadequate, and the consequences are becoming more pronounced in terms of both scale and complexity. The regions most severely affected by drought and desertification are concentrated in the northeastern part of Nigeria.[19][21][20] Rain-fed agriculture serves as the primary source of food production and livelihood for many impoverished rural farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa, including Nigeria.[22] In the Manga Grasslands of northeastern Nigeria, subsistence farmers primarily rely on agriculture for their sustenance and have been grappling with recurrent droughts since the 1970s.[23] The frequent occurrence of drought has also presented formidable challenges to traditional farming systems in northeastern Nigeria, where the predominant economic activities revolve around subsistence farming and nomadic livestock herding.[23]

The Sahel region was profoundly affected by severe drought during the 1970s, resulting in widespread famine and leaving millions of people in a state of starvation.[24] These drought episodes persisted for approximately five to six years, affecting millions of individuals in northern Nigeria. The consequences of these episodes were dire, leading to famine and the displacement of millions of people, effectively creating environmental refugees.[24] Various Sahelian nations, including Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, and Niger Republic, garnered substantial international attention and support in response to these crises. Notably, the number of people affected in northern Nigeria surpassed the combined impact on the other Sahelian countries.[24] The relatively limited international media coverage can be attributed to Nigeria's economic stability, largely due to its national oil wealth. The northern Nigerian states that were severely impacted by the 1970s droughts are those adjacent to Niger Republic. Agriculture, which contributes 18.4% to the national GDP in Nigeria, witnessed a sharp decline following the 1970s droughts, plummeting to a mere 7.3% of GDP. Consequently, many Nigerians in the northern region fell into dire poverty and experienced acute food shortages.[25]

Droughts are common in Nigeria, especially in the northern and central parts of the country, where the climate is semi-arid or arid. Some of the severe droughts that have affected Nigeria include:[26]

- The 1913–1914 drought that caused famine and starvation in northern Nigeria.[27]

- The 1942–1944 drought that affected most parts of Nigeria and caused food shortages and malnutrition.[27]

- The 1972–1974 drought that affected the Sahel region and caused famine and starvation in northern Nigeria and other countries. It was one of the worst droughts in Africa’s history, affecting about 100 million people and killing about 250,000 people.[27] The drought of 1972 and 1973 was attributed to the death of 13% of animals in the north-eastern Nigeria and an annual agricultural yield loss of more than 50%.[28]

- The rainfall trend between 1960 and 1990 in northeast Nigeria has steadily declined by about 8 mm/year.[29]

- Nigeria's most recent drought was between 1991 and 1995.[29][30]

Rainfall in northeastern Nigeria between the period 1994 to 2004 shows that the total annual rainfall range from 500 to over 1000 mm.[29]

Drought problem is accelerating desertification.[31]

Desertification

The concept of desertification was initially discussed by European and American scientists before Aubrevile in 1949. This discussion revolved around increased sand movement, desiccation, desert encroachment, and human-induced desert formation. According to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), desertification refers to land degradation occurring in arid, semi-arid, and humid regions due to various factors, including climate variations and human activities.[32] Several crucial aspects contribute to the definition of desertification:

- Climate and human activities as the underlying causes

- The susceptibility of arid and semi-arid lands

- The consequences of land degradation and loss of biodiversity.

Desertification is a process that results in land degradation due to prevailing climatic conditions and human activities, rendering the environment unable to sustain the demands imposed by socio-economic systems at existing technological and economic levels.[33][34][35] Desertification involves the formation and expansion of degraded areas of soil and vegetation cover in arid, semi-arid, and seasonally dry regions, influenced by climate variations and human activities.[36] It entails the stripping and degradation of once-fertile land, initiating a self-perpetuating cycle that leads to long-term changes in soil, climate, and biota within an area.[37]

Desertification can be viewed as a process in which the productivity of arid or semi-arid land decreases by 10% or more.[38] Mild desertification signifies a 10 to 25% reduction in productivity, while serious desertification indicates a 25 to 50% decline, and severe desertification denotes a productivity drop exceeding 50%. Desertification represents an advanced stage of land degradation where soil loses its capacity to support human communities and ecosystems. In regions experiencing desertification, people, in their pursuit of sustenance and livelihoods for the population, engage in land management and farming practices that deplete soil nutrients, organic matter, and promote erosion. This includes overgrazing of rangelands and the felling of trees and shrubs for fuel and other purposes.[39]

The direct consequence of desertification on land degradation manifests as either reduced land productivity or the complete abandonment of agricultural land, ultimately contributing to the food crises frequently witnessed in arid and semi-arid regions, especially in Africa. There is a direct correlation between drought, desertification, and food security. These environmental challenges result in diminished soil quality, which in turn leads to reduced agricultural productivity—a pivotal factor affecting food security.

Key features of a desertification process encompass:

- The impoverishment of vegetative cover

- Diminished availability and accessibility of soil moisture

- Deterioration of soil texture, structure, and nutrient status

- Reduced biodiversity and the prevalence of xeric biota

- Increased soil erosion.

The Nigerian environment and extent of desertification

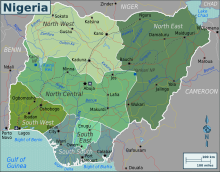

Nigeria is situated between approximately latitudes 4o and 14o north of the equator and longitudes 2o 2' and 14o 30' east of the Greenwich Meridian. It shares its borders with the Republics of Niger and Chad to the north, the Republic of Cameroon to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and the Republic of Benin to the west. Nigeria is a vast country with a population estimated at over 160 million people. A substantial portion of its land area extends into the Sudano-Sahelian belt, which, along with the neighboring northern Guinea savannah, constitutes the drylands of the country. The country covers an estimated total surface area of 909,890 km2. Approximately 40% of this land remains unused for settlement, agriculture, and other human purposes.[40] Nigeria experiences a warm tropical climate with relatively high temperatures typical of the tropics and two distinct seasons: the dry and wet seasons. While the extreme southern tip of the country hardly experiences a dry season, the northeastern part has a wet season lasting no longer than three months. Annual rainfall varies widely, from over 2,500 mm in the south to less than 400 mm in parts of the extreme north.[41] Northern Nigeria is located in semi-arid regions bordering the Sahara Desert, receiving an average annual rainfall of less than 600 mm.[42] This rainfall pattern has contributed to desertification encroachment in the northernmost states of Nigeria.

The extent and severity of desertification in northern Nigeria have not been fully determined, and the rate of progression remains inadequately documented. However, there are reports suggesting a desertification progression rate of approximately 0.6 km per year, with recent estimates indicating that approximately 351,000 km2 of land in northern Nigeria has already been affected by desertification.[43] According to the desertification map of the world jointly produced by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), and UNESCO, roughly 15% of Nigeria's land is susceptible to desertification.[44]

A visible sign of this phenomenon is the gradual transformation of vegetation from grasses, bushes, and occasional trees to primarily grass and bushes. In the final stage, expansive areas of desert-like sand become prevalent. It has been estimated that between 50% and 75% of states in Nigeria, including Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Jigawa, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, Yobe, and Zamfara, are affected to varying degrees by desertification. There are 15 desertification frontline states in Nigeria out of the total of 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory. These states collectively account for about 63.83% of Nigeria's total land area with a moderate to severe rate of desertification. Approximately 62 million Nigerians are either directly or indirectly impacted by desertification-related issues.

Causes of drought and desertification

The causes of both drought and desertification are multifaceted and intricate, stemming primarily from the intricate interplay between climatic factors and human activities in the environment. These causes encompass:

Climatic Variability: Climatic variations serve as a significant catalyst for numerous environmental degradation issues. Modifications in climatic conditions give rise to natural events like drought and desertification. The surge in greenhouse gases, which leads to global warming, intensifies climate variability. These alterations in climatic conditions manifest as follows:

- A reduction in rainfall in arid and semi-arid regions, rendering these areas more susceptible to desertification.

- Elevated temperatures, coupled with decreased rainfall, leading to the depletion of water resources and resulting in drought.

- Hindered growth of vegetation, culminating in conditions akin to desert formation. A study spanning from 1901 to 2005 revealed that Nigeria is not exempt from the effects of climate variability and global warming. These phenomena have had discernible localized impacts, particularly in highly industrialized urban centers and northern Nigeria. The observed environmental degradation includes an increase in average temperatures by 1.1 °C and a decrease in annual rainfall by an average of 81 mm.[45]

Anthropogenic Activities: Human actions have been a primary contributor to desertification, much like various other ecological degradation problems. Humans play a role in desertification through ill-advised land utilization practices and the mounting pressure placed on finite resources due to population growth. Essentially, human-induced desertification is a result of the exploitation of "non-ideal lands," excessive resource exploitation, unsustainable practices, and the failure to replace or allow adequate time for the natural regeneration of depleted resources. Human activities leading to desertification include:

- Deforestation: This involves the conversion of forested regions into non-forested areas to fulfill various human needs. Logging, expansion of agricultural croplands, urbanization, fuel wood collection, mining, and resource extraction, as well as fire-hunting and slash-and-burn practices, have been identified as key drivers of deforestation. Nigeria holds the unfortunate distinction of being one of the world's most severely deforested countries, having lost approximately 55.7% of its primary forests. Between 1990 and 2010, Nigeria witnessed a nearly 50% reduction in its primary forest cover, with an annual deforestation rate of 3.67% between 2000 and 2010. Alarmingly, the situation is dire, with the FAO stating that Nigeria's forests may disappear by 2020 if the current rate of depletion persists unabated.[45] Deforestation in drylands leads to the removal of trees and vegetation that stabilize the soil. Given the prevailing climatic conditions in drylands, the potential for vegetation regeneration is low, thereby contributing to desertification.

- Extensive Cultivation: The expansion of agricultural lands to meet the growing food demands of the burgeoning population has resulted in land degradation in Northern Nigeria. New lands are cleared of trees and other vegetation to establish agricultural croplands in dryland areas. Many of these lands are unable to recover, leading to desertification. Overgrazing and over-cultivation have been identified as the causes of the conversion of 351,000 hectares of land into desert each year in Nigeria.

- Overgrazing: Overgrazing is particularly prevalent in regions where the socio-economic viability heavily depends on an extrinsic system of animal husbandry. The drylands of Nigeria are said to support a significant portion of the country's livestock economy, hosting about 90% of the cattle population, approximately two-thirds of the goat and sheep population, and nearly all the donkeys, camels, and horses. In the Sudan and Sahel zones, which house a substantial livestock population, nomadic herders graze their livestock extensively across the area, constantly seeking suitable pastures. Natural rangelands are further strained by livestock from neighboring countries, notably Cameroon, Chad, and Niger. Overgrazing depletes vegetation cover, which safeguards the soil from erosion,[46] and degrades natural vegetation, contributing to desertification and a decrease in the quality of rangelands. Between 1950 and 2006, the Nigerian livestock population expanded from 6 to 66 million, an eleven-fold increase. The forage needs of livestock surpass the carrying capacity of its grasslands.[47]

- Cultivation of Marginal Land: Cultivation of marginal areas is one of the contributors to desertification. Marginal lands are areas incapable of sustaining permanent or intensive agriculture and are prone to degradation following cultivation. During periods of heavy rainfall, people tend to extend farming into these marginal areas. If these rainy periods are followed by sudden dry spells, the exposed land with minimal vegetative cover becomes susceptible to wind erosion, potentially leading to desertification. Reversing these effects may be challenging unless a carefully planned rehabilitation program is implemented.

- Bush Burning: Slash-and-burn agricultural practices and fire-hunting are significant contributors to desertification in northern Nigeria. The combination of low relative humidity and dry harmattan winds in the region results in frequent bushfires during dry seasons. Frequent bushfires can hinder vegetation regeneration, expose soil to erosion, and contribute to soil degradation.

- Fuelwood Extraction: Due to the socio-economic status of inhabitants in Nigeria's drylands, the felling of trees for fuelwood continues to rise unless alternative sources of energy are provided in the Sudano-Sahelian zone. The demand for fuelwood leads to the removal of trees, shrubs, herbaceous plants, and grass cover from fragile land, accelerating soil degradation to desert-like conditions. In Nigeria, over 70% of the population depends on fuelwood. In a northern state like Katsina, over 90% of energy is derived from fuelwood. In Kano City, 75,000 tonnes of fuelwood are transported by truck and donkey within a 20 km radius, depleting woodlands.

- Faulty Irrigation Management: Irrigation systems are commonly used in northern Nigeria. Many farmers lack the necessary skills for designing and managing irrigation systems, resulting in desertification-like conditions on several irrigated farmlands due to waterlogging and salinization. Some irrigation projects in Nigeria, such as the Bakolori Irrigation, South Chad Irrigation, and Hadejia – Jamaare Irrigation Projects, are already experiencing these problems. The drying up of Lake Chad, initiated during the Sahelian drought of 1972 to 1973, was exacerbated by poorly managed irrigation systems in the Chad Basin. This led to the lake's reduction from 25,000 m2 in 1963 to about 3,000 m2 in 1986, prompting the government to cease all irrigation projects in the basin in 1989 because the lake level had dropped 3 meters below the critical threshold.

- Urbanization: Rapid economic growth and urbanization have been linked to desertification. This issue is more complex and severe in developing countries. Land clearance to accommodate the growing population and essential infrastructure in northern Nigeria is often carried out without due consideration for the environment. This results in the removal of vegetation cover, contributing to desertification. Urbanization in Kano City, for example, has been estimated to be growing at a rate of 5% to 10% annually.[41] Around 20,000 hectares of land are cleared annually for construction.

Impacts of desertification in Nigeria

1. Ecological Impact

- Habitat Destruction and Biodiversity Loss: The process of desertification threatens many species and leads to a reduction in biodiversity, as the composition, abundance, distribution, and relationships among living organisms in arid and semi-arid ecosystems are disrupted.[48] Notably, various animal and plant species important to humankind, such as the sitodunga antelope, cheetah, giraffe, lion, and elephants in northern Nigeria, are now endangered due to desertification.[49]

- Changes in Phenology: Desertification also impacts the timing of biological events (phenology) for living organisms, affecting their behaviors, such as reproduction, mating, feeding, and migration, in response to altered climatic and environmental conditions.

2. Health Impacts

- Heat Waves: With the loss of dense vegetation cover due to desertification, the incidence of heat waves in northern Nigeria has increased, posing health risks to the population. These heat waves can lead to health problems, including heat exhaustion and cardiovascular diseases.[50]

- Cancer: Excessive exposure to direct sunlight, a consequence of reduced vegetation cover, is linked to skin diseases and cancer. Skin malignancies are more prevalent in areas affected by severe desertification, with regional variations in Nigeria.[51]

- Vector-Borne Diseases: Desertification, which alters temperature, precipitation, and climatic patterns, influences the range and seasonality of vector-borne diseases. Additionally, insufficient water supply in desertifying areas leads to increased contamination of available water sources, enhancing the transmission of waterborne diseases such as typhoid, infectious hepatitis, and cholera.[52]

- Loss of Medicinal Plants: Desertification has contributed to the loss of plants with medicinal properties, particularly woody species, which are sources of medicine for local communities. These medicinal plants are at risk of extinction, especially in arid and semi-arid lands.[53][54]

3. Geochemical Impacts

- Global Warming: Desertification disrupts the carbon sequestration capacity of vegetation and soil, increasing carbon levels in the atmosphere and exacerbating global warming.[55] In northern Nigeria, this has been associated with an average temperature increase of at least 1 °C.[56]

- Increased Erosion: Loss of soil's natural vegetation cover due to desertification is a major driver of soil erosion, with wind and water erosion causing widespread degradation (Katsina State survey). Gully erosion, previously less significant in Nigeria, has increased significantly, resulting in damage to agricultural lands.[57]

- Soil Salinization: In arid northern Nigeria, agricultural sustainability often relies on irrigation, which predisposes areas to saline soils and reduced crop productivity if not properly managed.[58]

4. Hydrological Impacts

- Reduced Water Supply: Desertification affects water availability, with over-exploitation of groundwater and drying up of wetlands and water sources, increasing water scarcity in affected regions. The decline in water resources can significantly impact ecosystem resilience.[59]

- Over-Exploitation of Groundwater: To meet the demands of growing populations, northern Nigeria heavily relies on groundwater, which is often extracted faster than it can be naturally replenished. This excessive use leads to a decline in groundwater levels and can result in land subsidence (sinking) (cone of depression) or aquifer collapse on a broader scale.

5. Socio-economic Impacts

- Reduced Agricultural Productivity and Food Insecurity: Desertification leads to reduced agricultural output, exacerbating food insecurity, as agriculture is the main source of livelihood for many people in Nigeria.[57] In areas affected by desertification, like Yobe State, farmlands have been covered by sand dunes, affecting the livelihood of thousands of farmers.

- Economic Loss and Reduced Economic Growth: Desertification weakens communities, making them more vulnerable to global economic factors. Reduced agricultural productivity leads to lower tax receipts, affecting government finances and necessitating increased reliance on food imports. The government spends substantial resources on mitigating the effects of desertification, which could have been allocated to other development projects (Sokoto and Borno States).

- Migration: Desertification often leads to population migration as people abandon unproductive rural areas in search of employment in urban centers. This migration can lead to family separation and increased disease transmission (Hadejia/Nguru/Kirri-Kissama wetland project).

- Resource Use Conflict: Competition for limited, seasonally critical resources such as land and water resources often lead to conflicts between different groups, such as farmers, herders, and fishermen, notably in northern Nigeria (Plateau State, Benue State, etc.).

- Unemployment: Migration due to desertification often results in unemployment in urban areas, leading to the creation of slums and socioeconomic difficulties (slums).[60][61]

Flood

Flooding can arise from intense precipitation or when rivers and seas breach their usual boundaries due to elevated tides, submerging land areas. This occurs when lakes, ponds, riverbeds, soil, and vegetation are unable to absorb all the water, leading to an excess that flows over the land, overwhelming stream channels or surpassing the capacity of lakes, natural ponds, or man-made reservoirs. The situation can be worsened by an increased number of impermeable surfaces, as well as natural events like wildfires or deforestation that diminish the vegetation available to absorb rainfall.[62] Floods have various causes and types. Flash floods, characterized by swiftly rising and perilous water traveling at high velocities, can occur suddenly. Coastal flooding in oceans is driven by storm surges, hurricanes, and tsunamis. Failures of dams or other water-retention structures can also lead to flooding. In recent years, climate change and global warming have emerged as significant contributors to flooding.[63]

Climate change poses a threat to impeding progress out of poverty in developing nations, particularly in Africa.[64] Regardless of their scale, an uptick in disasters jeopardizes advancements in development.[65] Anticipated repercussions of climate change include heightened disaster risk in the next decade, characterized by more frequent and severe hazardous events, amplifying the vulnerability of communities already susceptible to these hazards.[65] Presently, there is a heightened focus on the Sustainable Development Goals, one of which involves addressing climate change and its ramifications by enhancing resilience, reducing climate-related hazards, and mitigating natural disasters.[66] The consequences of flooding in Nigeria mirror those experienced in various other countries like Mali, Senegal, Burkina Faso, and Niger,[67] though the response strategies may differ. Floods result in substantial losses encompassing property, infrastructure, businesses, and an escalated risk of diseases. When floods occur naturally away from human habitation, they offer numerous advantages.[68] However, if flooding takes place in areas extensively developed by humans, particularly densely populated regions, what was once a natural occurrence transforms into a catastrophe. Shortly after flooding, sanitation deteriorates, and the risk of disease outbreaks, particularly among displaced individuals, escalates (WHO n.d.). The contamination of drinkable water by pollutants from overflowing sanitation facilities raises the probability of waterborne illnesses like typhoid fever, cholera, leptospirosis, and hepatitis A (WHO n.d.). Frequently, those in poverty are more susceptible and severely impacted.[69] Health impacts resulting from floods are divided into short- and long-term effects.[70] Globally, mortality rates often rise by up to 50% in the first year following a major flood event, and psychological distress can persist for up to 2 years after the flood disaster, affecting 8.6% to 53% of the population.[70]

Recurrent flood in different parts of Nigeria had led to considerable socio-economic damage, injury and loss of life. Some of the negative consequences of flood include loss of human life, damage to properties, public transportation systems, power supply, crops, and livestock.[71]

2022

The 2022 Nigeria floods affected many parts of the country. From the Federal Government Data, the floods had displaced over 1.4 million people, killed over 603 people, and injured more than 2,400 people. About 82,035 houses had been damaged, and 332,327 hectares of land had also been affected.[72]

While Nigeria typically experiences seasonal flooding, this flood was the worst in the country since the 2012 floods.[73]2021

In August, a flood happened in Adamawa state, affecting 79 communities in 16 local government areas. Reports says that seven people lost their lives and about 74,713 others displaced became homeless;[74][75] While 150 farmlands and about 66 houses were destroyed according to Adamawa state Emergency Management Agency (ADSEMA).[76]

2020

In 2020, 68 people died and 129,000 people were displaced due to the 2020 flood incidences. This is according to the NEMA Director-General, Muhammadu Muhammed.[77][78]

2017

The 2017 Benue State flooding took place in September 2017 in Central Nigeria.[79] Weeks of rainfall led to flash floods, discharges and river flowing in Benue State. It displaced 100,000 people,[80][81] and damaged around 2,000 homes.[82]

2012

2010

Around 1000 residents of Lagos and Ogun states region of Nigeria were displaced due to flood associated with heavy rainfalls, which was further exacerbated by the release of water from the Oyan Dam into the Ogun River[87]

About 250,000 Nigerians were affected by the flooding in 2016, while 92,000 were affected in 2017[88][89][90]

2023

On 3 March 2023, there was a heavy downpour and rainstorm in Oke-Ako in the Ikole Local Government Area of Ekiti State. The situation lasted for over two hours and destroyed about 105 houses. The heavy downpour of rain also destroyed some electricity infrastructure across the town, subjecting the residents to total blackout.[91]

The Ekiti State governor, Mr. Biodun Oyebanji, through his deputy Mrs. Monisade Afuye, described the incidents as devastating and assured the victims that government would give all the necessary support to mitigate whatever effect this situation must have caused them. [92]

Farmers and community efforts to mitigate floods in Nigeria.

Annual flooding is increasing in intensity, leaving farmers more exposed to the adverse impacts of climate change. A study carried out in Akwa Ibom, Ondo, and Rivers states revealed that farmers commonly employ land management practices, particularly utilizing mounds, to alleviate the effects of flooding. Approximately 30% of male farmers and 39% of female farmers utilize this approach.[93]

In the wetland areas of Ondo state, farmers cultivate flood-resistant or flood-tolerant crop varieties. Additionally, farmers have diversified their sources of income to adapt to environmental hazards. Fishing communities in Akwa Ibom, Ondo, and Rivers states have adjusted to flooding and rising sea levels by fishing farther from the shore and equipping themselves with deep freezers to preserve their catch during extended periods at sea.[94]

A study investigated the Ilajes, Itshekiris, and Ijaw tribes residing in coastal rural communities.[95] This study revealed that these communities possess traditional knowledge of local meteorological patterns based on observation and traditional practices, aiding them in predicting flooding on a seasonal and long-term basis.

Efforts made by institutions and government agencies to mitigate flood in Nigeria.

Numerous workshops were organized across the country to brainstorm flood management strategies aligned with global best practices. The Flood Research Group at the Federal University, Otuoke, located in Bayelsa state within the Niger Delta region, which was among the states affected by the 2012 flood, collaborated with the Bayelsa state government of Nigeria to host a post-flood management workshop. The proposed flood impact, control, and mitigation strategies include implementing effective drainage systems, constructing buffer dams strategically, planning house construction to prevent obstruction of natural drainages and waterways, preventing siltation of creeks, rivers, and other water bodies through dredging, establishing a well-organized community flood preparedness program, conducting sensitization campaigns, and managing floods on a regular basis. This program should encompass continuous monitoring of soil saturation and water levels, enhancing grassroots awareness of weather forecasts, conducting necessary evacuation drills, and providing emergency self-help and survival training for communities.[96]

To mitigate the impact of flood disasters in the nation, the federal government initiated an early warning system after major flood incidents in prominent cities such as Lagos, Kano, and Kaduna. This system underwent an upgrade in 2014. The Federal Ministry of Environment deployed 307 web-based flood warning systems nationwide. Furthermore, community-based flood warning systems were set up in various states, including Ondo, Niger, Cross River, Imo, Anambra, Lagos, Oyo, Osun, Ogun, Nassarawa, Rivers, Kwara, Akwa Ibom, Abia, and Enugu. The ministry also procured and installed four standalone automated functional flood early warning facilities along Alamutu, Eruwa, and Owena River basins.[97]

To notify the public about impending flooding dangers, the federal government empowered the Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NIMET) to provide precise weather forecasts. Additionally, a sum of N17 billion was disbursed to affected states and other relevant stakeholders to alleviate the effects of the 2012 floods. Plans are underway to construct multipurpose dams like Kashimbilla/Gamovo, Ose Dam, and a hydropower project in Taraba state to manage the excessive water flow from Cameroon whenever it occurs. These dams will serve to mitigate flooding, generate electricity, create employment, enhance irrigation, and boost agricultural production in Nigeria.[98]

The government has taken steps to relocate individuals residing in flood-prone areas. In South-eastern Benue, government authorities relocated forty communities to safer locations.[99] The Kogi state government advised residents of communities along riverbanks to relocate following a warning of water release from Kainji and Jebba Dams. The government also urged state residents to clear their drainages to enable unobstructed water flow and prevent flooding.[100]

The lessons gleaned from the 2012 flood guided agencies like the Red Cross in enhancing their emergency response. The Nigerian Red Cross trained 22,000 volunteers and stocked warehouses with relief supplies. The National Environmental Management Agency urged dam management officials to lower water levels in a timely manner, emphasizing not waiting for water levels to breach the dams before releasing it to minimize flooding risks. Flood-prone communities received training and basic equipment to facilitate swift evacuation.[99] The National Space Research and Development Agency (NASRDA) produced a floodplain and vulnerability map, utilized by the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) to aid in the rehabilitation of those affected by the 2012 flood.[101]

Landslides

Landslides are not very common in Nigeria, but they do occur occasionally in some parts of the country, especially in hilly or mountainous areas with steep slopes or unstable soils.[102] Some of the major landslides that have occurred in Nigeria include:

- The 2006 Abeokuta landslide that killed over 20 people when a hill collapsed on a residential area after heavy rainfall.[citation needed]

- The 2010 Owerri landslide that killed over 10 people when a hillside collapsed on a hotel building after heavy rainfall.[103][104]

- The 2012 Agwagune landslide that killed over 40 people when a cliff collapsed on a fishing village after heavy rainfall.[105]

- The 2017 Mokwa-Jebba landslide that blocked a major highway linking northern and southern Nigeria after heavy rainfall.[106][107]

- The 2018 Nanka landslide that destroyed several houses and farmlands after heavy rainfall.[108]

Earthquakes

Earthquakes happen worldwide, and different countries experience varying levels of seismic activity. Some nations have frequent earthquakes, while others rarely encounter them, and a few are entirely free from such events. Nigeria is among the countries that have experienced relatively low and infrequent seismic activity. While most of the recorded earthquakes in Nigeria have been of small to medium magnitudes, there have also been a few instances of medium to large magnitude earthquakes documented. This seismic activity in Nigeria is attributed to the country's geological setting, which is situated within the mobile belt of Africa, positioned between the Congo Craton and the West Africa Craton. Significant damage and deformations were documented within this region in the past, which had some impact on the neighboring craton. This pertains to the Pan-African orogeny, a geological event that occurred approximately 600 to 100 million years ago and is considered the most recent of its kind. This geological history may explain why Nigeria has historically experienced very few earthquakes.[109]

In the past, it was widely believed that Nigeria was entirely immune to seismic hazards because no seismic events were recorded in its history. However, seismic events have occurred in Nigeria in recent years, challenging this belief. Many of these seismic incidents, such as tremors, went unrecorded in the past due to the lack of adequate seismic monitoring equipment in Nigeria at the time. Subsequently, earthquakes and tremors have been observed and recorded in the country. As we consider the seismic activity in Nigeria, it's important to note that any potential future earthquakes are likely to happen along the fault lines within Nigeria. Recent developments have also indicated that both West Africa and Nigeria are at risk of experiencing devastating earthquakes in the future.[110][111] Numerous earthquakes and tremors have been documented in Nigeria over the years, and these seismic events are scattered across the country's geopolitical zones. Nigeria is divided into six geopolitical zones, each with its own distinct geographical characteristics. These zones are known as the North-Central Zone (NC), North-East Zone (NE), North-West Zone (NW), South-East Zone (SE), South-South Zone (SS), and South-West Zone (SW). A detailed breakdown of these six geopolitical zones in Nigeria is provided by[112] as follows:

- North Central (commonly referred to as the Middle Belt): This zone includes the states of Benue, Kogi, Kwara, Nasarawa, Niger, Plateau, and Abuja.

- North East: Encompassing the states of Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba, and Yobe.

- North West: Consisting of Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, and Zamfara states.

- South East: Comprising the states of Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, and Imo.

- South South: This zone includes the states of Akwa Ibom, Cross River, Bayelsa, Rivers, Delta, and Edo.

- South West: Encompassing Ekiti, Lagos, Ogun, Ondo, Osun, and Oyo states.

Earthquakes are rare in Nigeria, but they do occur occasionally in some parts of the country, especially in areas with active or dormant fault lines or volcanic activity. Some of the minor earthquakes that have been recorded in Nigeria include:[113]

- The 1933 Biu earthquake that measured 5.8 on the Richter scale and caused some damage in Borno state.[114][115]

- The 1984 Kaduna earthquake that measured 4.3 on the Richter scale and caused some panic in Kaduna state.[116]

- The 1990 Ijebu-Ode earthquake that measured 4.5 on the Richter scale and caused some alarm in Ogun state.[117]

- The 2000 Abuja earthquake that measured 3.8 on the Richter scale and caused some tremors in Abuja.[118][119]

- The 2004 Kwoi earthquake that measured 4.2 on the Richter scale and caused some cracks in buildings in Kaduna state.[120]

- The 2009 Abeokuta earthquake that measured 3.9 on the Richter scale and caused some vibrations in Ogun state.[121]

- The 2016 Saki earthquake that measured 4.3 on the Richter scale and caused some shaking in Oyo state.[122][123]

- The 2018 Abuja earthquake that measured 3.0 on the Richter scale and caused some fear in Abuja.[124][125]

The very first earthquake in Nigeria was documented in 1939 in Ibadan, while the initial tremor was noted in Warri in 1933. Since then, several other earthquakes have occurred. Notably, on September 11, 2009, at approximately 03:10:30 am in Abeokuta, a significant earthquake with an intensity of VII and a magnitude of 4.8 was observed. Researchers from the National Space Research and Development Agency (NARSDA) confirmed this event, dispelling the notion that Nigeria is immune to earthquake hazards. Consequently, there has been a growing emphasis on the safety of the nation's infrastructure.[126]

The southwestern region of Nigeria has witnessed a higher frequency of earthquakes compared to other geopolitical zones in the country. This suggests that this particular zone is more susceptible to earthquakes than others in Nigeria. Recently, the Nigerian Association of Water-Well Drilling Rig Owners and Practitioners (AWDROP) urged the Nigerian government to take action aimed at mitigating or minimizing the consequences of potential earthquakes. AWDROP drew the government's attention to a prediction made by a group of researchers, led by Dr. Adepelumi Adekunle Abraham from the Department of Geology at Obafemi Awolowo University in Ile Ife. Their report, titled "Preliminary Assessment of Earth Tremor Occurrence in Shaki Area, Shaki West Local Government, Oyo State," points to an impending seismic threat. The head of AWDROP also emphasized that the unregulated extraction of underground water could potentially induce earthquakes. Consequently, strict adherence to the implementation of relevant codes of practice is essential.[127]

Probable Reasons of Earthquake Occurrence in Nigeria

Despite the past belief that Nigeria was free from seismic activities, several earthquakes have been observed in recent times. Therefore, Nigeria cannot be considered completely immune to seismic events. While there are countries like China and Japan that are actively seismic, Nigeria does not fall into this category yet. Researchers have sought to understand the underlying reasons for earthquakes in Nigeria. It has been proposed that Nigeria may experience earthquakes due to the stresses generated between the African plate and the South American plate, which apply pressure to the coastal areas within this boundary. As suggested by,[128] these stresses resulting from the movement of the African and South American plates might be transmitted to Nigeria, leading to the occurrence of earth tremors along fault lines.

Earthquake Forecast in Nigeria

In recent years, various seismic alerts and forecasts have been issued by agencies and researchers in Nigeria. Notable among these forecasts are those provided by.[128][129][130] According to the forecast by,[128] it was projected that a magnitude ≥ 5.0 earthquake might occur in the southwest region of Nigeria between 2010 and 2028. The probability of this event increased from 6% to 91.1% within that time frame.

To address the knowledge gap regarding the potential future earthquakes in Nigeria,[129][128] conducted research. Their findings revealed that Nigeria, despite being a country with low seismic activity, could experience a future earthquake with a magnitude as high as 7.2 in the southwest region. It is essential to consider that even regions with low seismicity, such as Antarctica as reported by,[131] have experienced significant earthquakes, like the 8.1 magnitude quake in 1998. Therefore, Nigeria, despite its low seismic activity, could indeed experience earthquakes as indicated by these researchers' forecasts.

Seismic Stations in Nigeria

The occurrence of recent earth tremors in Nigeria has come as a significant surprise to many Nigerians. West Africa is traditionally perceived as a region with low seismic activity and is often seen as stable in terms of seismic events. Worldwide, millions of earthquakes of varying magnitudes occur each year, ranging from minor tremors detectable only by sensitive recording instruments to large quakes capable of causing significant human and infrastructural damage. The global distribution of earthquakes provides valuable insights into the seismicity of different regions around the world.

Earthquakes and volcanic activities are typically associated with the boundaries of tectonic plates, as outlined by the plate tectonics theory. However, there are recorded instances of intraplate earthquakes occurring. Despite the relative distance of West Africa from tectonic plate boundaries, some of its regions have experienced destructive earthquakes. One significant challenge in Nigeria has been the lack of comprehensive earthquake data collection efforts, which has persisted for a considerable period. This data gap has had a notable impact on the seismic records for the country.

While numerous tremors have been officially recorded in Nigeria from as far back as 1933 to recent times, it's important to acknowledge that many tremors have likely gone undetected due to limited recording technology during certain periods in the country's history.[132]

Nigeria has adopted a gradual approach to enhance its seismic data collection capabilities, resulting in the establishment of five active seismic stations within the country. However, the nation has ambitious plans to further expand the distribution of seismic stations across its territory. The Center for Geodesy and Geodynamics (CGG) in Toro is responsible for monitoring and researching seismic events in Nigeria. The currently operational seismic stations are equipped with advanced 24-bit 4-channel data acquisition systems and broadband seismometers. It is anticipated that telemetry equipment will soon be integrated into these stations' features.

Fire Outbreak

A fire outbreak can be considered a natural disaster when it is ignited and spreads due to natural factors like lightning strikes, volcanic eruptions, or wildfires caused by natural conditions such as drought or high winds. When fire is primarily driven by natural forces and occurs in wildland areas, it is often referred to as a "wildfire." Wildfires can cause significant damage to ecosystems, property, and can pose serious threats to human life, making them natural disasters. However, not all fire outbreaks are natural disasters. Human activities, such as accidental fires, arson, or industrial incidents, can also lead to fires. In these cases, the fire outbreak is not a natural disaster but is instead a human-made or anthropogenic disaster. The distinction between a natural disaster and a human-made disaster lies in the primary causes and factors that lead to the disaster. A fire disaster can be defined as an event that takes place when a flammable substance makes contact with oxygen, resulting in the release of light, heat, and smoke. It is essentially a chemical reaction where the stored heat in a combustible material is unleashed along with the emission of light and smoke. While fire offers numerous advantages, its potential for widespread destruction poses a significant threat to a nation's fragile economy. Fire outbreaks are among the most common and devastating disasters worldwide, and they have been a persistent issue, particularly in developing countries. Given the detrimental impact of fires on both the environment and the economy, there has been a growing emphasis on strategies aimed at preventing, controlling, or extinguishing them when they occur.[133]

The spread of fire within a structure often involves the occurrence of diffusion flames. Pyrolysis products are released from heated solid fuel and mix with the surrounding air at the combustion point. Sometimes, this mixing happens at a significant distance from the solid fuel source. When fuel and air combine before the actual combustion, the ignition of this fuel-air mixture can release a substantial amount of energy. Successful combustion requires the correct proportion of fuel and oxygen, as well as sufficient heat energy to initiate the reaction. Heat serves as the necessary energy to raise the fuel's temperature to a point where enough vapors are emitted for ignition to take place. However, in many cases, this process is notably more complex. For instance, in a typical building fire, the diverse array of fuels such as furniture, clothing, paper, plastics, and other household combustibles, combined with limited ventilation, generates a complex, toxic, and flammable mixture of solids, gases, and vapors through an oxidation reaction.[134][135]

Fires occur naturally when the essential elements are present and properly mixed, and a fire can be prevented or extinguished by removing any one of the elements in the fire triangle. For example, covering a fire with a fire blanket eliminates the oxygen component of the triangle and can extinguish the fire. While the fire triangle consists of fuel, heat, and oxygen, other materials can significantly influence how a fire progresses. Non-combustible materials absorb heat energy, slowing down the ignition and combustion processes. A straightforward way to illustrate this concept is by taking two sheets of newspaper, spraying one with a fine mist of water, and attempting to ignite each sheet. The moist sheet becomes challenging, if not impossible, to burn due to the need for the heat source to raise the water's temperature and vaporize it from the fuel. Materials that absorb heat but do not actively participate in the combustion reaction are known as thermal ballast. Understanding this concept is crucial for comprehending fire development, and it can also be effective in fire control or reducing the likelihood of a rapid fire's progression.[134]

Effects of Fire Disasters in Nigeria

The impact of a fire outbreak is profound, encompassing both emotional distress and physical damage. Fire poses a threat to both life and property, and its behavior is highly unpredictable. People are often deeply affected by what they witness during and after a fire incident. The most significant predictor of post-fire distress seems to be the frightening nature of the fire experience and the extent of the losses incurred. When a fire disaster occurs, those affected often must initially relocate their family members to a safe location, leading to a host of additional challenges. These challenges may include finding immediate shelter, securing food, water, clothing, financial resources, and permanent housing.

Unlike natural disasters, where an entire community may suffer similar losses, fires frequently target individual homes. Families forced to evacuate may need to seek refuge with extended family members, neighbors, or friends. This temporary separation can add to the overall stress of the situation. Losing one's home and personal belongings can result in depression and heightened levels of distress, potentially leading to post-traumatic stress disorder. In the aftermath of a fire disaster, families may grapple with financial difficulties and health issues. Parents may find themselves bewildered and frustrated as they navigate interactions with insurance companies and disaster relief agencies. Furthermore, the cumulative emotional toll of evacuation, displacement, relocation, and rebuilding should not be underestimated.

After a fire, it's common for individuals to encounter sensory cues like sights, sounds, smells, and feelings that serve as reminders of the fire and their losses. The process of physical and emotional recovery following a fire can be an extended one. Children and families who have experienced residential fires may continue to worry about the possibility of another fire, which can lead to increased concerns about the safety of their loved ones, friends, neighbors, and more. These individuals may experience heightened distress and anxiety when confronted with reminders of the fire incident.[135]

Cases of fire outbreak in Nigeria

Based on information obtained from the Lagos State Fire Service, there were approximately 68 cases of market fires reported and addressed within Lagos State between 2012 and 2013. These incidents affected a total of 40 distinct markets across 16 Local Government Areas in the state. It's important to note that both the urban and rural areas of Lagos were affected by these significant market fires. Among the 16 local government areas in the urban region, 14 of them witnessed market fires, and among the 4 local government areas in the rural region, 2 experienced such incidents during the study period.[136]

Emergency management

National Emergency Relief Agency (NERA)

The National Emergency Relief Agency (NERA) was created by Decree 48 of 1976 in response to a devastating flood incidence between 1972 and 1973.[137][138] NERA was a post disaster management agency with sole focus on coordination and distribution of relief material to disaster victims.[138][28]

National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA)

The National Emergency Management Agency is an agency in Nigeria.[139] The agency focuses on disaster management in all parts of the country.[139] The agency was established in 1999,[140] and functions to formulate policies relating to disaster management in Nigeria.

Director generals included:

- Muhammad Sani-Sidi

- Abbas Idriss[141]

The National Disaster Management Framework of Nigeria (NDMF) framework was created in 2010 to serve as legal instruments to guide stakeholders' engagement with respect disaster management in Nigeria.[144] It was created to foster effective and efficient disaster management among Federal, State and Local Governments, Civil Society Organizations and the private sector. NDMF has 7 focus areas and a sufficiency criteria, namely:

- Institutional Capacity

- Coordination

- Disaster Risk Assessment

- Disaster Risk Reduction

- Disaster Prevention, Preparedness and Mitigation

- Disaster Response

- Disaster Recovery

- Facilitators and Enablers

National Drought Management Committee (NDMC)

The National Drought Management Committee (NDMC) was establishment in 1985 to coordinate drought management activities in Nigeria.

Nigeria Geological Survey Agency (NGSA)

The Nigerian Geological Survey Agency (NGSA) was establishment in 2006 to provide geoscientific data and information for land use planning and natural hazard management in Nigeria.

Centre for Geodesy and Geodynamics (CGG)

The Centre for Geodesy and Geodynamics (CGG) was establishment in 2008 to provide geophysical data and information for earthquake monitoring and early warning in Nigeria.[145]

See also

References

- ^ Nigeria, Guardian (2023-01-24). "Over 2 million Nigerians displaced by flood in 2022, says NEMA". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ Onu, Steve I. (2019). "Natural Hazards Governance in Nigeria". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Natural Hazard Science. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199389407.013.236. ISBN 978-0-19-938940-7.

- ^ "Impact Of Flooding In Nigeria". Leadership News. 30 November 2022.

- ^ Church, Deirdre L. (September 2004). "Major factors affecting the emergence and re-emergence of infectious diseases". Clinics in Laboratory Medicine. 24 (3): 559–586. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2004.05.008. PMC 7119055. PMID 15325056.

- ^ "Emerging Infectious Diseases". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 2019-11-19. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ Newsline, Church of the Brethren (2022-09-29). "Nigerian communities suffer natural and man-made disasters – News". Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ "man-made disasters in nigeria - Google Search". www.google.com. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ "Nigeria has encountered several forms of disaster, which range from flooding, soil and coastal erosion, landslides, tidal waves, coastal erosion, sand-storms, oil spillage, locust/insect infestations, and other man-made disasters. - Google Search". www.google.com. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ "Katsina residents panic over two-day hailstone". Punch Newspapers. 2022-09-12. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ^ pulse.ng. "It's raining ice in Abuja and residents are over the moon". Pulse.ng.

- ^ Wilhite, Donald A.; Glantz, Michael H. (1985). "Understanding: the Drought Phenomenon: The Role of Definitions". Water International. 10 (3): 111–120. Bibcode:1985WatIn..10..111W. doi:10.1080/02508068508686328. ISSN 0250-8060.

- ^ A.F. Van Loon, G. Laaha. Hydrological drought severity explained by climate and catchment characteristics. J. Hydrol., 19 (2014), pp. 1-12

- ^ a b A. Yaduvanshi, K.S. Prashant, A.C. Pandey. Integrating TRMM and MODIS satellite with socio-economic vulnerability for monitoring drought risk over a tropical region of India. Phys. Chem. Earth, 6 (2015), pp. 8-22

- ^ S.M. Vicente-Serrano, S. Beguería, L. Gimeno, L. Eklundh, G. Giuliani, D. Weston, A. El Kenawy, J.I. López-Moreno, R. Nieto, T. Ayenew, D. Konte. Challenges for drought mitigation in Africa: the potential use of geospatial data and drought information systems. Appl. Geogr., 34 (2012), pp. 471-486

- ^ B. Shiferaw, T. Kindie, K. Menale, A. Tsedeke, B.M. Prasanna, M. Abebe. Managing vulnerability to drought and enhancing livelihood resilience in sub-Saharan Africa: technological, institutional and policy options. Weather and Climate Extremes, 3 (2014), pp. 67-79

- ^ U. Habiba, S. Rajib, Y. Takeuchi. Farmer's perception and adaptation practices to cope with drought: perspectives from northwestern Bangladesh. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 1 (2012), pp. 72-84

- ^ C.T. West, C. Roncoli, F. Ouattara. Local perceptions and regional climate trends on the Central Plateau of Burkina Faso. Land Degrad. Dev., 19 (3) (2008), pp. 289-304

- ^ Sheikh BA, Soomro GH (2006). Desertification: Causes, Consequences and Remedies. Pak. J. Agric. Agric. Eng. Vet. Sci. 22(1): 44-51.

- ^ a b T.E. Olagunju. Drought, desertification and the Nigerian environment: a review. J. Ecol. Nat. Environ., 7 (7) (2015), pp. 196-209

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b H.G. Abdullahi, M.A. Fullen, D. Oloke. Socio-economic effects of drought in the semi-arid Sahel: a review International Journal of Advances in Science Engineering and Technology, 1 (2016), pp. 95-99

- ^ E. Elijah, M. Ikusemoran, K.J. Nyanganji, H.U. Mshelia. Detecting and monitoring desertification indicators in Yobe State, Nigeria. Journal of Environmental issues and Agriculture in Developing Countries, 9 (1) (2017), pp. 22-34

- ^ P.J.M. Cooper, J. Dimes, K.P.C. Rao, B. Shapiro, S. Twolmlow Coping better with current climatic variability in the rain-fed farming systems of sub-Saharan Africa: an essential first step in adapting to future climate change? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 126 (1–2) (2008), pp. 24-35

- ^ a b A.B. Alhassan, R.C. Carter, I. Audu Agriculture in the oasis of the Manga Grasslands of semi-arid north-east Nigeria: how sustainable is it? Outlook Agric., 32 (3) (2003), pp. 191-195

- ^ a b c M. Mortimore Adapting to Drought: Farmers, Famine and Desertification in West Africa Cambridge University Press (1989)

- ^ I.U. Abubakar, M.A. Yamusa Recurrence of drought in Nigeria: causes, effects and mitigation Int. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol., 4 (3) (2013), pp. 169-180

- ^ Abubakar, I.U; Yamusa, M.A. "Recurrence of Drought in Nigeria: Causes, Effects and Mitigation". International Journal of Agriculture and Food Science Technology. 4 (2249–3050): 169–180.

- ^ a b c "The 1913–1914 drought that caused famine and starvation in northern Nigeria. – Google Search". www.google.com. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ a b Disaster management and data needs in Nigeria (PDF). 2014.

- ^ a b c "Federal Republic of Nigeria" (PDF). knowledge.unccd.int. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ "The 1913–1914 drought that caused famine and starvation in northern Nigeria. – Google Search". www.google.com. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ "What is desertification? Discover its causes and consequences". Iberdrola. Retrieved 2023-10-19.

- ^ UNCCD (1997). United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. http://www.unccd.int

- ^ Campbell DJ (1986). The prospect for desertification in Kajiado district, Kenya. Geogr. J. 152:44-55.

- ^ Mortimore M (1989). Adapting to drought: farmers, famines, and desertification in West Africa. Cambridge University Press. pp.12. ISBN 978-0-521-32312-3

- ^ Oladipo EO (1993). A comprehensive approach to drought and desertification in Northern Nigeria. Nat. Hazards 8(3): 235-261.

- ^ Wright RT and Nebel BJ (2002). Environmental Science: Towards A Sustainable Future. New Jersey. Pearson Education Inc.

- ^ Cunningham WP, Cunningham M, Saigo B (2005). Environmental Science: A Global Concern. New York. McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Miller GT (1999). Environment Science: Working with Earth. New York. Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- ^ Acosta-Michlik L, Klein RJT, Compe K (2005). How vulnerable is India to climatic stress? Measuring vulnerability to drought using the Security Diagrams concept. Human Security and Climate Change 1:21-23

- ^ National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) (2010). Annual Abstract of Statics 2010. pp. 4

- ^ a b Federal Ministry of Environment of Nigeria (1994). A report on National Action Programme to Combat Desertification in Nigeria

- ^ Folaji MB (2007). Combating Environmental Degradation in Nigeria: A Case Study of Desertification in Kano State. A College paper submitted to the Armed Forces Command and Staff College Jaji Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) (2006).

- ^ Nwafor JC (2006). Environmental Impact Assessment for sustainable Development. Enugu. EDPCA Publishers

- ^ Emodi EE (2013). Drought and Dsertification as they affect Nigerian Environment. J. Environ. Manage. Saf. 4(1): 45-54

- ^ a b Onyeanusi AE, Otegbeye GO (2012). The impact of Deforestation on Soil Erosion and on the Socio-economic Life of Nigerians. Sustainable Environmental Management in Nigeria, Book Builders publisher, Nigeria. pp. 315-331.

- ^ UNCCD (2011). Desertification: A visual Synthesis. GRAPHI 4 Press, Bresson France. pp. 1-52.

- ^ Lester RB (2006). The Earth is shrinking: Advancing Deserts and Rising Seas Squeezing Civilization. Earth Policy Institute. www.earthpolicy.org/update.

- ^ Bullock P, Le Houerou H (1994). Land degradation and Desertification, Chapter 4, pp. 173-185.

- ^ NAP (2000). The National Action Programme to Combat Desertification and Mitigate the Effect of Drought Federal Ministry of Environment, Abuja, Nigeria.

- ^ Bell ML, Goldberg R, Hogrefe C, Kinney PL, Knowlton K, Lynn B (2007). Climate Change, ambient ozone, and health in 50 US cities. Clim. Change 82 (1-2): 61-76.

- ^ McMichael AJ, Githeko A (2001). Human Health. In: Climate Change: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the IPCC.

- ^ Betterton C, Gadzama NM (1987). Effects of Drought on Public Health. In: V. O. Sagua et al (eds) Ecological Disasters in Nigeria: Drought and Desertification Federal Ministry of Science and Technology, Lagos. pp. 204-210.

- ^ Kafaru E (1994). Immense Help from Natutres's Workshop. Elikaf Health Services Ltd. p.212.

- ^ Otegbeye GO, Otegbeye EY (2002). Socio-economics. In: Agroforestry and Land Management Practices Diagnostic Survey of Katsina State of Nigeria, G.O. Otegbeye, editor, Katsina State Agricultural and Rural Development Authority, Katsina, pp. 63-79.

- ^ Bruce JP, Lee H, Haites EF (1996). Climate Change: Economic and Social Dimensions of Climate Change. Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Olagunju TE (2015b). Forest Transition: Towards Modulating Climate Change. Nat. Sci. 13(5): 86-91

- ^ a b Toye O (2002). Desertification Threatens Economy, Food Security. TerraViva; the unofficial record of the United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development. An IPS-Inter Press Service Independent Publication. Johannesburg, South Africa, 26 August Issue.

- ^ Jibrin JM, Abubakar SZ, Suleiman A (2008). Soil Fertility Status of the Kano River Irrigation Project Area in the Sudan Savanna of Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. 8: 692-696.

- ^ Batanouny KH (1998). Biodiversity strategy and Rangelands in the Arab World. Paper presented at the Workshop on National Biodiversity Planning, Arabian Gulf University, 12–14 October 1998, Bahrain. p.17.

- ^ Pasternak D, Schlissel A (2001). Combating desertification with plants. Springer. p.20. ISBN 978-0-306-46632-8.

- ^ Briassoulis H (2005). Policy integration for complex environment problems: the example of Mediterranean desertification. Ashgate publishing. p.161. ISBN 978-0-7546-4243-5

- ^ Ayooso, S. (2012). How to Check Floods in Nigeria, The Tide [Online] Available: http://www.thetidenewsonline.com/2012/07/05/how-to-check-floods-in-nigeria/

- ^ Famous, F.O. (2012). Mitigating the impact of flood disasters in Nigeria. Pointblank News. [Online] Available: http://pointblanknews.com/pbn/articles-opinions/mitigating-the-impact-of-flood-disasters-in-nigeria/

- ^ Lemos, M.C. & Tompkins, E.L., 2008, ‘Responding to the risk from climate related disasters’, id21 highlights Climate Change. UK: IDS, page 1-4

- ^ a b ISDR, 2008, Disaster risk reduction strategies and risk management practices: Critical elements for adaptation to climate change, viewed 20 December 2013, from www.unisdr.org/.../risk-reduction/climate-change/.../IASC-ISDR_paper_cc_and_ DDR.pdf

- ^ UN, 2017, The sustainable development goals report 2017, United Nations, New York, viewed 19 August 2018, from http://sdgactioncampaign.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/TheSustainableDevelopmentGoalsReport2017.pdf.

- ^ OCHA, 2016, West Africa: Impacts of the floods, viewed 19 August 2018, from https:// www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/ documents/files/wca_a4_l_impact_of_floods_20160822.pdf.

- ^ Opperman, J.J., Galloway, G.E. & Duvail, S., 2013, ‘The multiple benefits of riverfloodplain connectivity for people and biodiversity’, in S. Levin (ed.), Encyclopedia of biodiversity, 2nd edn., pp. 144–160, Academic Press, Waltham, MA.

- ^ Yamin, A., 2014, Why are the poor the most vulnerable to climatic hazards (e.g. floods)? A case study of Pakistan., Term paper. University of Potsdam, Germany pp. 1–19.

- ^ a b Alderman, K., Turner, L.R. & Tong, S., 2012, ‘Foods and human health: A systematic review’, Environment International 47, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint</. 2012.06.003

- ^ Ajumobi, Victor Emeka; Womboh, SooveBenki; Ezem, Sebhaziba Benjamin (January 2023). "Impacts of the 2022 Flooding on the Residents of Yenagoa, Bayelsa State, Nigeria". Greener Journal of Environmental Management and Public Safety. 11 (1): 1–6.

- ^ Oguntola, Tunde (2022-10-17). "2022 Flood: 603 Dead, 1.3m Displaced Across Nigeria – Federal Govt". Retrieved 2022-11-07.

- ^ Maclean, Ruth (17 October 2022). "Nigeria Floods Kill Hundreds and Displace Over a Million". The New York Times.

- ^ "7 killed, 74,000 displaced by flood in Adamawa". Vanguard News. 2021-08-26. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- ^ Ochetenwu, Jim (2021-08-26). "Floods claim 7, displaces 74, 713 Adamawa people in 2 weeks". Daily Post Nigeria. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- ^ "Flood sacks Adamawa community, destroys 150 farmlands, 66 houses". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. 2021-08-14. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- ^ "Flooding affects 129,000 across Nigeria, kills 68 — NEMA". 2020-12-07. Retrieved 2021-10-22.

- ^ "Floods killed 68, displaced 129, 000 in 35 states, FCT, in 2020 — NEMA". Vanguard News. 2020-12-07. Retrieved 2021-10-22.

- ^ "More than 100,000 displaced by flooding in central Nigeria". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- ^ "Nigeria – Thousands Displaced by Floods in Benue State – FloodList". floodlist.com. Copernicus. 5 September 2017. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- ^ Al Jazeera (1 September 2017). "Nigeria floods displace more than 100,000 people". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- ^ "Flood Hits Makurdi, Ravages Over 2,000 Homes • Channels Television". Channels Television. 2017-08-27. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- ^ Susan, Agada. "A serious flooding event in Nigeria in 2012 with specific focus on Benue State: a brief review".

- ^ "NIGERIA: Worst flooding in decades". IRIN Africa. October 10, 2012. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ "Nigeria floods test government's disaster plans". The Guardian. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ "2012 flood disaster cost Nigeria N2.6tn –NEMA". punchng.com. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ Chioma, Olanrewaju C.; Chitakira, Munyaradzi; Olanrewaju, Oludolapo O.; Louw, Elretha (18 April 2019). "Impacts of flood disasters in Nigeria: A critical evaluation of health implications and management". Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies. 11 (1): 557. doi:10.4102/jamba.v11i1.557. PMC 6494919. PMID 31061689.

- ^ "Nigeria Struggling to Cope With Rising Natural Disasters". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2021-10-22.

- ^ "Nigerian and U.S. Flooding Similar, Linked to Climate Change". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Why does Nigeria keep flooding?". BBC News. 2018-09-26. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Ekiti: Rainstorm wreaks havoc, destroys 105 buildings, several homeless". 7 March 2023.

- ^ "Many homeless as rainstorm destroys houses in Ekiti". 5 March 2023.

- ^ Umoh, G. S. (2013), Adaptation to Climate Change: Agricultural Ecosystems and Gender Dimensions, Xlibris Corporation, 121-129.

- ^ Umoh, G. S. (2013), Adaptation to Climate Change: Agricultural Ecosystems and Gender Dimensions, Xlibris Corporation, 121-129

- ^ Fabiyi, O.O., & Oloukoi, J. (2013). Indigenous Knowledge System and local adaptation strategies to flooding in coastal rural communities of Nigeria. Journal of Indigenous Social Development, 1(2), 1-19, [Online] Available: http://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/handle/10125/29817/v2i1_05fabiyi.pdf?sequence=1

- ^ Federal University, Otuoke. (2013). FU Otuoke collaborates with Bayelsa State Govt on flood management. [Online] Available: http://www.fuotuoke.edu.ng/news/2013-09/fu-otuoke-collaborates-bayelsa-state-govt-flood management

- ^ Okoruwa, E. (2014). FG Installs 307 flood warning systems nationwide. Leadership. [Online] Available: http://leadership.ng/news/378685/fg-installs-307-flood-warning-systems-nationwide

- ^ Anugwara, B., & Emakpe, G. (2013). Will FG save Nigerians from another` Tsunami’? [Online] Available: http://www.mynewswatchtimesng.com/will-fg-save-nigerians-another-tsunami/

- ^ a b The Guardian. (2013). Nigeria floods test government’s disaster plans. [Online] Available: http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2013/aug/28/nigeria-floods-disaster

- ^ Anugwara, B., & Emakpe, G. (2013). Will FG save Nigerians from another` Tsunami’? [Online] Available: http://www.mynewswatchtimesng.com/will-fg-save-nigerians-another-tsunami

- ^ Odeh, O. (2014). 2012 flood disaster: Nigeria still not free. Daily Independent. [Online] Available: http://dailyindependentnig.com/2014/03/2012-flood-disaster-nigeria-still-not-free/

- ^ Bamisaiye, O. A. (July 2019). "Landslide in parts of southwestern Nigeria". SN Applied Sciences. 1 (7). doi:10.1007/s42452-019-0757-0. S2CID 197557409.

- ^ Nigeria, Guardian (2020-05-01). "Eight storey building under construction collapses in Owerri". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ "8-story building gave way in Nigeria: At least 2 casualties". www.thestructuralengineer.info. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ "Agwagune Community Ravaged by Landslide". 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Lamentation of users of collapsed Jebba/Mokwa bridge". Tribune Online. 2017-06-30. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ Bissolli, P.; Ganter, C.; Li, T.; Mekonnen, A.; Sanchez-Lugo, A. (August 2018). "7. REGIONAL CLIMATES" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 99 (8): S193. Gale A556571308.

- ^ Igwe, Ogbonnaya; Una, Chuku Okoro (December 2019). "Landslide impacts and management in Nanka area, Southeast Nigeria". Geoenvironmental Disasters. 6 (1): 5. Bibcode:2019GeoDi...6....5I. doi:10.1186/s40677-019-0122-z. S2CID 189980873.

- ^ M. S. Tsalha, U. Lar, T. A. Yakubu, U. A. Kadiri and D. Duncan, "The Review of the Historical and Recent Seismic Activity in Nigeria," Journal of Applied Geology and Geophysics, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 48-56, 2015.

- ^ A. K. Umar, A. Y. Tahir, U. A. Ofonime, D. Duncan and U. E. Saturday, "Towards an integrated seismic hazard monitoring in Nigeria using geophysical and geodetic techniques," International Journal of the Physical Sciences, pp. 6385-6393, 2011.

- ^ J. Oluwafemi, O. Ofuyatan, A. Ede, B. Ngene, S. Oyebisi and O. Oshokoya, "Simulated Response of Buildings to Earthquake In The South-Western Region of Nigeria," International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology, 2018 (in-press).

- ^ T. C. Eze, C. S. Okpala and J. C. Ogbodo, "Patterns of Inequality in Human Development Across Nigeria‟s Six Geopolitical Zones," Developing Country Studies, pp. 97-101, 2014.

- ^ Nwankwoala, H. O.; Orji, O. M. (12 December 2018). "An Overview of Earthquakes and Tremors in Nigeria: Occurrences, Distributions and Implications for Monitoring". International Journal of Geology and Earth Sciences. 4 (4): 56. doi:10.32937/IJGES.4.4.2018.56-76. S2CID 187570345.

- ^ "Earthquakes in Biu, Borno, Nigeria - Most Recent". earthquaketrack.com. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ "Latest Earthquakes in Biu, Borno State, Nigeria, Today: Past 24 Hours". www.volcanodiscovery.com. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ "Earth tremors in Kaduna State". Daily Trust. 2016-09-13. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ "The 1990 Ijebu-Ode earthquake that measured 4.5 on the Richter scale and caused some alarm in Ogun state. - Google Search". www.google.com. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ Nigeria, Guardian (2018-09-23). "Abuja earth tremor as warning signal". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ "The 2000 Abuja earthquake that measured 3.8 on the Richter scale and caused some tremors in Abuja. - Google Search". www.google.com. Retrieved 2023-07-11.

- ^ "The 2004 Kwoi earthquake that measured 4.2 on the Richter scale and caused some cracks in buildings in Kaduna state. - Google Search". www.google.com. Retrieved 2023-07-11.