Contents

Esteban de Bilbao Eguía, 1st Marquess of Bilbao Eguía (11 January 1879 – 23 September 1970) was a Spanish politician during the dictatorship of Francisco Franco.

Family and youth

Esteban Martín Higinio de Bilbao Eguía[1] was born to a Basque mid-range bourgeoisie family. His paternal grandfather, Manuel Bilbao, ran a merchant business in his native town of Guernica (Biscay province);[2] one of his sons became a presbyter,[3] while another, Hilario Bilbao Ortúzar, moved to Bilbao and practiced as a physician.[4] He married María Concepción Matea de Eguía Galindez, descendant to a distinguished and much-branched Biscay family.[5] The couple had 6 children, with Esteban born[6] as the oldest of 2 brothers and 4 sisters.[7] All Bilbao Eguía children were brought up in a fervently Catholic ambience, though none of the sources consulted provides any information on political preferences of their parents.

The young Esteban was first educated at Instituto Provincial, the local state-run Bilbao secondary education establishment.[8] Sources provide different details of his exact academic path, though most agree that he studied law and philosophy first in the Jesuit university of Deusto in Bilbao, later moving to the prestigious Universidad de Salamanca and completing both curriculums.[9] Bilbao crowned his scientific career obtaining PhD laurels in law in Universidad Central of Madrid.[10] Having returned to his native Biscay he opened the law office[11] and in 1904 was registered as practicing abogado in Bilbao.[12] In 1913 he married María de Uribasterra e Ibarrondo (1891-1976).[13] The couple had no issue.[14]

Early public activity

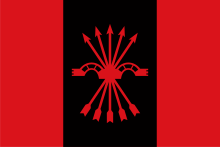

It is unclear whether Bilbao inherited the Carlist outlook from his forefathers or whether he rather embraced it during the academic years. In 1902 he was already firmly established in local Biscay structures of mainstream Carlism, and together with national pundits like Juan Vázquez de Mella toured the province, organizing meetings and delivering speeches.[15] In 1904 he ran as a Carlist[16] in elections to the Bilbao City Council and was successful;[17] some sources claim he was later nominated teniente de alcalde.[18] As he objected to presence of a Protestant minister during an official municipal act,[19] the government charged him with breaching the constitution and cancelled his mandate.[20]

Pursuing Catholic militancy against mounting secularization promoted by Madrid governments, Bilbao played pivotal role in the Biscay Juventud Católica;[21] he also threw himself into a number of other local Catholic initiatives, e.g. representing Carlism at public meetings against secular schools.[22] His activities climaxed at the turn of the decades, during public uproar caused by the so-called Ley del Candado. Forming part of the Biscay Junta Católica he took part in countless gatherings and events, the most notable of them Acto de Zumarraga of 1910.[23] As some of his harangues bordered legality he was three times trialed, though the outcome is unknown.[24]

Within the Traditionalist ranks Bilbao together with other Deusto students Victor Pradera and Julio Urquijo formed a new generation of activists, promoted by the claimant Carlos VII and the party leader marqués de Cerralbo in their bid to build a modern Carlist network.[25] In 1907 he was fielded as the official party candidate to the Cortes from the Álavese district of Vitoria. His debut turned to be a fratricidal war, since another Carlist, Enrique Ortiz de Zarate, competed backed by the youth and more militant electorate;[26] as a result, both Carlists lost.[27] In 1910 Bilbao was rumored to replace Vazquez de Mella as a Jaimist candidate in the Navarrese Pamplona, but eventually it was the latter who stood and won.[28] In the successive campaign of 1914 Bilbao ran in his native Biscay, in Durango, but lost again, this time to a conservative candidate, José de Amézola y Aspizua,[29] with ensuing riots between supporters of both candidates.[30]

Bilbao embraced the Basque self the Carlist way, defending local provincial fueros and ethnic identity as indispensable elements constituting the common Spanish political nation. He took part in the first Congreso de Estudios Vascos[31] and was given a privilege of delivering the closing address; when speaking, he commiserated with persecuted "madre Euskal Herria" and voiced in favor of a Basque university, which would carry out the work of "restauración cultural vasca".[32] He remained active also during the following congresses until the late 1920s and played vital role in its Sección de Estudios Sociales;[33] he demonstrated interest in the social question also beyond the Basque realm,[34] publishing a leaflet "La cuestion social".[35]

Cortes and Asamblea Nacional

Following unsuccessful electoral campaigns in Álava, Navarre and Biscay, in 1916 Bilbao competed in the Carlist national stronghold, the Gipuzkoan district of Tolosa. He defeated the conservative candidate[36] and formed part of the 9-member Jaimist minority in the Cortes. In 1918 he stood in the same district and was re-elected.[37] Active defending the Church, religion and Traditionalism,[38] he distinguished himself as one of the most notable Carlist orators,[39] though by some he is described as having a penchant for purple rhetoric.[40]

During the Mellista crisis Bilbao remained loyal to successive claimant Don Jaime[41] and worked closely with him, editing some of his proclamations and documents.[42] As the secession decimated the Jaimist ranks, Bilbao became the local Biscay jefe[43] and in 1919 he was fielded as provincial Jaimist candidate to the Senate.[44] Elected, he remained active working on syndical laws and autonomous status of the universities.[45] It is not clear why in 1920 he abandoned his senatorial status and decided to run for the Cortes again; this time he returned to Navarre and was elected from another Carlist stronghold, the Estella district.[46] In 1923, during the last parliamentarian campaign of the Restoration, the Carlist king ordered abstention and no official candidates were fielded.[47]

Though most Carlists welcomed the Primo de Rivera coup, considering it a stepping stone towards a traditionalist, anti-democratic monarchy, their sympathy soon evaporated and Don Jaime obliged his followers not to enter the primoderiverista institutions. Bilbao ignored the ban and remained one of the most vocal advocates of the dictatorship.[48] In 1924 he joined the new state party, Unión Patriótica;[49] in 1926 he was nominated president of Diputación de Bizkaia[50] and holding the job for 4 years he worked to negotiate the provincial concierto económico;[51] finally, in 1927 he joined the newly appointed quasi-parliament, Asamblea Nacional Consultiva[52] as a representative of diputaciones provinciales.[53] It is not clear which of these acts was the straw which broke the camel's back; Don Jaime and his political representative in Spain marqués de Villores remained firm and expulsed Bilbao from the party ranks.[54] Retaining his Carlist identity, Bilbao approached the Mellista branch of Traditionalism.[55]

He remained active also as a Catholic politician, since the early 1920s heading the Biscay section of Acción Católica;[56] he later took part in the first national congress and delivered an address.[57] In 1929 he worked to launch a new Catholic political grouping, but the initiative came to naught as it was greeted with at best lukewarm reception from the primate Segura.[58] During the Dictablanda period Bilbao approached the orphaned monarchist primoderiveristas from Unión Monárquica Nacional, speaking at their public meetings.[59]

Republic

Sources consulted provide contradictory information on Bilbao's relations with mainstream Carlism after the fall of the monarchy. Some authors claim that though many Carlists felt that advent of the militantly secular Republic required unification of various Traditionalist branches, Bilbao was not enthusiastic about returning under the command of Don Jaime.[60] Other scholars maintain that already in April 1931 he edited the claimant's proclamation, which instructed the Carlists to help maintain order and to stay alert to the threat of foreign-inspired tyranny.[61] Equally incompatible is the information that in late 1931 and early 1932 Bilbao brokered a failed dynastical agreement with the deposed Alfonso XIII.[62]

Following unexpected death of Don Jaime Bilbao dashed any doubts he might have had and together with Pradera he led the Mellistas into the united Carlist organization, Comunión Tradicionalista, becoming head of its Biscay section[63] and joining the national Junta Suprema.[64] He forged close working relation with the new claimant, Don Alfonso Carlos, co-editing a number of his proclamations and documents,[65] including those which seemed to confirm the late Don Jaime's policy of opening dynastical negotiations with the Alfonsinos.[66] Himself he was also inclined towards a dynastical pact and is listed as one of the so-called "transaccionistas".[67] He engaged in the monarchist alliance and contributed to Acción Española.[68] Some sources claim he joined the manifesto launching a new broad alliance, Bloque Nacional,[69] while other authors maintain he was one of the few leaders who did not sign.[70]

From the onset Bilbao contributed to the Carlist military buildup. In the summer of 1931 he was in touch with Comité de Acción Jaimista, an organization launched to gather vigilantes protecting religious buildings.[71] He was agreed to enter the monarchist military junta, to be headed by general Emilio Barrera, in October 1931 briefly detained[72] and in early 1932 administered 2 months of exile in Navia de Suarna (Lugo province).[73] He was at least aware of and possibly somehow involved in the Sanjurjo coup,[74] though the authorities did not identify Bilbao as complicit. Opposing dissolution of the Jesuit order and enforcement of secular schools cost him further detentions and two court trials.[75]

In 1933 Bilbao resumed his parliament duties elected as a Carlist deputy from Navarre;[76] he later defended traditional Navarrese fueros,[77] though he voiced against the autonomy of Catalonia.[78] The same year together with other party pundits like Jesús Comín he entered the 18-member Council of Culture, the body which exercised little power, but brought together Carlists of different origins and strengthened the new leadership of Manuel Fal Conde.[79] In 1935 Bilbao reached the highest level of Carlist executive when he entered the 5-member Council of the Comunión.[80] Within the already militant and fervently anti-Republican Traditionalist camp Bilbao formed an even more hawkish group; he refused to stand in the 1936 elections for his self-proclaimed hatred of parliamentarism.[81]

Civil War

It is not clear how Bilbao contributed to the military conspiracy and what was his position in Carlist debates on conditions of their access to the rebellion; during the July 1936 coup he was in his summer home in Durango.[82] Detained by the Basque authorities on the Altunamendi ship,[83] in late September, thanks mostly to the efforts of Marcel Junod, he was exchanged for the Bilbao mayor Ernesto Ercoreca[84] and made it via France to the Nationalist zone.[85] He entered Junta Nacional Carlista de Guerra and was nominated member of its Sección Politica,[86] settling close to Cuartel General del Generalissimo in Salamanca.[87]

Starting late 1936 Carlism was increasingly paralyzed by its unclear governing structure and political indecision, especially when cornered by Franco and his chief aide, Ramón Serrano Suñer. As member of the Carlist executive Bilbao took part at least in some meetings of early 1937, called to discuss the looming threat of amalgamation within a future state party. During the Insua gathering[88] he did not illude himself that a new regime would resemble the mild Primo's dictatorship; he seemed aware of the centralist, anti-regionalist design advanced by Franco and warned against "un gobierno definitivo de tipo falangista"[89] and the regime "fuerte, dictatorial y cesarista",[90] but nevertheless he tended to hesitantly accept the unification perspective against the intransigent fraction of Fal.[91] The semi-rebellious Carlist body, Junta Central Carlista de Guerra de Navarra, pursued an appeasing strategy and tried to assume leading role within the movement by suggesting a re-organization of Carlism; within this scheme, Bilbao was proposed to lead its Sección Politica.[92] Nothing came out of these plans as Franco pressed for action and soon declared his Unification Decree.

Faced with a choice between compliance of Rodezno and intransigence of Fal, Bilbao aligned himself with the Francoist unification and joined the newly established FET.[93] Though he was not among 4 Carlists who entered the first 10-member Secretariado of the party,[94] in October 1937 as one of 12 Traditionalists he was nominated into the totally decorative 50-member body, Consejo Nacional.[95] Vehemently asked by Fal Conde not to accept, Bilbao stuck to his guns[96] and in December 1937 the new regent-claimant Don Javier and Fal agreed to expulse him from the Comunión.[97] With all bridges burnt, following transformation of the Secretariat into Junta Politica, the new FET executive, Bilbao emerged as one of two top-positioned Carlists of the regime, becoming the Junta's member in October 1939. He exercised little if any influence on the emerging party; its Estatuto and internal structures were designed by Serrano,[98] who – together with his Falangist entourage – became Bilbao's chief opponent.[99] He rather excelled as a speaker, mobilising support at Vascongadas public feasts.[100]

Minister of Justice

In 1938 Bilbao became president of Comisión de codificación within the Francoist Ministry of Justice and commenced work on buildup of the Francoist legal code.[101] When his fellow Carlist, conde Rodezno, left the ministerial seat, in August 1939 Bilbao replaced him, holding the post until 1943.[102] As Minister of Justice he presided over one of the most repressive legal systems of modern Europe.[103]

In terms of number of judicial executions, early Francoist Spain exceeded Nazi Germany and was second only to the Soviet regime.[104] The number of death penalties sentenced in few years following the Civil War was 51,000,[105] though nearly half were reduced by Franco and there were some 28,000 people executed.[106] When assuming the ministry Bilbao oversaw the greatest single wave of incarcerations, which brought the number of political inmates from 100,000 at the end of the civil war to 270,000 by the end of 1939.[107] In the following years this figure dropped steadily thanks to a series of amnesties[108] and when leaving ministry he admitted to 75,000 political prisoners.[109] In the meantime, thousands of them died in overcrowded prisons.[110] Though labor camps in general remained under the military, his ministry provided juridical assistance, the end result having been some 90,000 people working in usually atrocious conditions in penal detachments.[111] Brutality of the system shocked even Heinrich Himmler.[112]

Bilbao coordinated work on the Francoist repressive legislation, with its cornerstones Ley de Responsabilidades Políticas (1939),[113] Ley de Represión de la Masonería y Communismo (1940)[114] and Ley de Seguridad del Estado (1941).[115] He developed appropriate juridical organization, e.g. setting up Tribunal Especial para la Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo.[116] As minister he contributed to legal groundwork for the so-called niños robados,[117] for Patronato Central de Redención de Penas por el Trabajo, with some 10,5 thousand children covered in 1943,[118] and for Patronato de Protección a la Mujer.[119] Under his guidance the divorce and marriage legislation of the Republic was retroactively reversed.[120]

While during Primo's dictatorship Bilbao as head of the Biscay Diputación defended local fueros, nothing is known about his stance on Francoist political penalty applied to Biscay and Gipuzkoa, considered "provincias traidoras" and stripped off any remnants of separate local establishments, especially the concierto economico.[121] However, Bilbao claims to have defended Navarrese fueros and to have prevented homogenization designs against the province, promoted by the Ministry of Economy.[122]

Dignitary

As Minister of Justice and the regime's top lawyer Bilbao gave shape to Ley Constitutiva de las Cortes (1942) and according to it he was doubly entitled – as member of Consejo Nacional and as a minister – to enter the Francoist quasi-parliament when it first assembled in 1943. As part of his balancing game, intended to keep different political groupings in check, Franco awarded the speaker role to the Carlists and handpicked Bilbao for the post.[123] He retained the position during 22 years and 8 successive turns, in 1946, 1949, 1952, 1955, 1958, 1961 and 1964,[124] until he resigned due to his age in 1965;[125] during his tenure there were some 4,000 laws adopted.[126] As Presidente de las Cortes Bilbao enjoyed one of the most prestigious and distinguished positions in the Francoist Spain, though there was very little if any political power attached. As one of the top-placed Carlists within the regime[127] Bilbao was also supposed to represent Traditionalist roots and broad political adherence to the regime.

Having sat 35 years in the Restauración parliament, the Primoderiverista Asamblea Nacional, the republican Cortes and the Francoist Cortes Españolas, Bilbao remains the longest serving 20th century Spanish deputy and one of the longest serving Spanish MPs ever.[128] His first and his last days in the diet are spanned by 49 years, which is also a record in Spanish parliamentary history.[129]

In 1947 he was the key author of Ley de Sucesión,[130] the law which officially established Spain as the monarchy and opened a vague path for royal restoration, at the same time stabilizing the rule of Franco as Jefe de Estado; it was protested by both Alfonsist and Carlist claimants, Don Juan and Don Javier.[131] According to the law, by virtue of his parliament speaker role Bilbao entered two newly established bodies: Consejo del Reino[132] and Consejo de Regencia. The former, a peculiar diarchic structure for an authoritarian monarchy proposed earlier by Primo de Rivera, was designed as a special deputy to the executive. It was supposed to assist the Head of State on matters falling into his exclusive competence and was presided by Bilbao himself.[133] The latter, composed of 3 officials, was to act as an interim regency during transition to Franco's successor or in his absence. The sole period it actually functioned was 9 days in October 1949, during the one and only Franco's foreign trip after the Civil War.[134]

Relations with Falangism

During 30 years of activity within the Francoist regime Bilbao maintained a perfectly loyal posture;[135] he was later given credit for coining the royally-sounding phrase "Francisco Franco, Caudillo de España por la gracia de Dios".[136] He is not known to have participated in any sort of conspiracy, opposition or even protest to Franco personally. His political efforts were principally directed at keeping the hardline Falangists at bay, occasionally combined with a rather timid advocacy of the monarchist idea.

In the summer of 1940 Ramón Serrano Suñer came out with Ley de Organización del Estado, a draft aimed at giving Falange central role in the totalitarian new structure. The plan elicited a letter of protest from Bilbao, who denounced "systematic interjection of the party" in the organs of the state. The dissent was shared by most monarchists and part of the army; as a result, the project was shelved and the Francoist system evolved along more hybrid lines.[137] Discontent between the Falange diehards and the monarchists made Bilbao resign as a minister early August 1942; he changed his mind having received a flattering letter from Franco.[138] Soon afterwards the Begoña incident produced a showdown between the Carlists and the Falangists, with general Varela demanding that Falange is brought into line and the monarchy restoration process begins.[139] Bilbao lent Varela his backing, but Franco outmaneuvered the dissidents and talked them into compliance,[140] though the standoff eventually led to sidetracking of Serrano and de-emphasizing of Falangism.[141] The last major confrontation between syndicalist hardliners and monarchists took place in late 1956; Bilbao compared Arrese's draft of Leyes Fundamentales to "Soviet totalitarianism" and led the coalition of monarchists, Catholic hierarchy and the military against the project;[142] the climax produced cabinet reshuffle, sidetracking of Arrese and ultimately power shifting to the technocrats.

Due to his age starting late 1950s Bilbao became sort of a decorative figure, until in 1965 he resigned from all political functions quoting his declining years.[143] As a private retiree he could have afforded more frankness and as late as 1969 he publicly expressed hardly veiled lack of enthusiasm for the perceived Falangist domination in the Cortes, be it during his presidency or afterwards.[144]

Relations with Carlism

Following his expulsion from the Comunión Bilbao's relations with mainstream Carlism were reduced to nil. When in late 1942 the Carlists dashed any hopes about preserving their identity within FET, Fal Conde declared that those previously expulsed might get re-admitted provided they break any links with Falange. Bilbao, however, was explicitly excluded from the scheme.[145] Lambasted by mainstream Carlists as double traitor who already abandoned Don Jaime in the 1920s,[146] Bilbao had even to take minor snubs in the Cortes.[147] He did not join Reclamación del poder, a protest letter signed by the Javieristas and delivered to Franco in 1943.

Though counted by Don Javier amongst "camaradas" of the treacherous Rodezno, Bilbao did not follow his course of approaching Don Juan as the legitimate Carlist claimant.[148] Instead, together with other Traditionalists like Joaquín Bau, Iturmendi or del Burgo, in 1943 he re-launched[149] the candidature of Karl Pius Habsburg, styled as Carlos VIII[150] and, within the limits permitted by the Francoist regime, he cautiously supported Carloctavismo[151] until the claimant unexpectedly died in 1953.[152] When in mid-1950s Carlism changed its strategy towards Francoism from opposition to cautious collaboration, the distance between Bilbao and the party shortened. The new breed of Carlist activists, especially the young anti-Traditionalist entourage of Don Javier's son, Carlos Hugo, were keen to use Bilbao in their own gamble for power.[153] Though they despised Bilbao as traitor,[154] in 1959 the group invited him to join Junta Directiva Central, a front-office sheltering their semi-political initiatives, like Círculos Culturales Vázquez de Mella or the Azada y asta periodical.[155]

Most probably the senile Bilbao was unaware of the power struggle already rife within Carlism, with reactionary Traditionalists confronted by the socialist Progressists. In 1963 as the Cortes speaker he sent a greeting telegram to the Carlist annual amassment at Montejurra, at that time serving as key event in the Huguista bid for power and as promotional stage for Carlos Hugo himself.[156] Already a political retiree and faced with perspective of Juan Carlos declared the future king, in 1969 Bilbao observed that it would not be intelligent to stumble twice over the same stone;[157] a year before death he voiced in favor of Don Javier.[158] The only notable Carlist present on his funeral was José Luis Zamanillo.[159]

Other, reception and legacy

Bilbao was member of many juridical bodies, first to be mentioned Real Academia de Jurisprudencia, which he led since 1946,[160] Real Academia de Ciencias Morales y Políticas[161] and Sección de Ciencias Jurídicas de la Academia de Bilbao.[162] Though he did not pursue academic career, Bilbao was temporarily professor of law at Universidad Libre de Vizcaya.[163] He presided over Asociación de antiguos alumnos de la Universidad de Deusto.[164] In 1947 awarded the Hijo Predilecto title from the Bilbao ayuntamiento[165] and the Hijo Benemerito title from the Diputación de Vizcaya;[166] in 1955 he was nominated honorary mayor of Durango.[167]

Though he is not acknowledged as a theorist and author, he wrote some works, spanning from history (La cuestión social: Aparisi y Guijarro 1941) to philosophy of law (La idea del orden como fundamiento de una filosofia política 1945), history of law (Jaime Balmes y el pensamiento filosófico actual 1949) and theory of law (La idea de la justicia y singularmente de la justicia social 1949, De la persona individual come sujeto primario en el Derecho Público 1949, De las teorias relativistas y su oposición a la idea del derecho romano 1953).[168] Collaborated with a number of newspapers and periodicals, like Diario de Navarra, El Fuerista, El Diario Vasco, El Pueblo Vasco, El Correo Español, La Gaceta del Norte, El Pensamiento Navarro and El Día.[169]

Bilbao was awarded Gran Cruz de la Orden de Isabel la Católica,[170] also decorated with Gran Cruz de Carlos III, Gran Cruz del Mérito Naval, Cruz Meritísima de San Raimunde do Peñafort and Gran Cruz de la Orden Plana.[171] In 1961 he was created Marquess of Bilbao Eguía (es:Marqués de Bilbao Eguía),[172] the title which upon his death passed to his brother, Hilario.[173] In 2006 Audiencia Naciónal, the Spanish high court, attempted to formally acknowledge Bilbao as a criminal guilty of crimes against humanity,[174] but due to procedural reasons this initiative bore no fruit. In contemporary Spanish public discourse he is sometimes referred to favorably as "Vasco de leyenda"[175] or neutrally as "en cierto modo el espécimen del politico vasco ultraconservador".[176] More frequently, however, he is highly criticized as "franquista"[177] or "fascista".[178] Leftist political groupings demand that his portrait is removed from the Spanish Cortes, where it is currently on display.[179] Bilbao has earned no monography so far, be it either a full-scale biography or a smaller piece.[180]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ not to be confused with a contemporary Basque trotskyist, Esteban Bilbao (?-1954), see marxist.org service available here

- ^ see the official service of Spanish senate, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 07.06.13, available here

- ^ see euskalnet service, available here

- ^ Eguia family explained in detail here

- ^ according to the birth certificate he was born in Bilbao, see here; some sources claim he was born in Durango, see Idioia Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry [in:] Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online, available here

- ^ see Geneallnet service available here

- ^ Gonzalo Díaz Díaz, Hombres y documentos de la filosofía española, vol. 1, Madrid 1980, ISBN 8400047265, 9788400047269, p. 591; according to another source, it was "Instituto general y tecnico", El Imparcial 16.05.28, available here2

- ^ according to Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry, he studied derecho and filosofia y letras at Deusto; according to Entrevista a Esteban Bilbao, [in:] Esfuerzo común 102 (1969), quoted after elcaballerodeltristedestino blog available here he studied filosofia y letras at Deusto, then moved to Salamanca where he graduated in law; according to Díaz Díaz 1980, p. 591 he studied filosofia and derecho at Deusto, but graduated in both in Salamanca

- ^ Entrevista a Esteban Bilbao, [in:] Esfuerzo común 102 (1969)

- ^ which in the mid-1920s would briefly employ the Basque political leader, José Aguirre, see Carlos Puerta Sesma, José Antonio Aguirre. Unidad didactica para la ESO, Donostia 2004, p. 10

- ^ Anuario Riera 2 (1904), p. 1695 available here

- ^ the spelling of her apellido is somewhat confused. When informing about the marriage, El Siglo Futuro 07.06.13 wrote "Urisbasterra", see here; when publishing her obituary, ABC 14.09.76 wrote "Uribasterra", see here, and this is the version repeated in almost all other works

- ^ see Geneallnet service available here; the euskalnet service wrongly claims that he fathered Hilario de Bilbao Eguía y Uribasterra, who was in fact Esteban's brother, see here

- ^ ABC 24.09.70, available here

- ^ from the Santiago quarter, ABC 24.09.70

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ Entrevista a Esteban Bilbao, [in:] Esfuerzo común 102 (1969); the same version is presented in El Imparcial 16.05.28, available here

- ^ namely cornerstone laying ceremony to monument of Juan Crisóstomo de Arriaga, ABC 24.09.70

- ^ Javier Sánchez Erauski, El nudo corredizo: Euskal Herria bajo el primer franquismo, Tafalla 1994, ISBN 8481369144, 9788481369144, p. 213

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 08.10.11, available here, also El Siglo Futuro 05.11.12, available here

- ^ Cristóbal Robles, Cristóbal Robles Muñoz, José María de Urquijo e Ybarra: opinión, religión y poder, Madrid 1997, ISBN 9788400076689, p. 233

- ^ see the manifesto published at nodulo.org service, available here

- ^ ABC 24.09.70; see also Robles, Robles Muñoz 1997, p. 252

- ^ José Luis Orella Martínez, El origen del primer catolicismo social español [PhD thesis at Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Madrid 2012, p. 223; in 1910 Bilbao was already president of the local Circulo Tradicionalista, see Robles, Robles Muñoz 1997, p. 246

- ^ even the Catholic hierarchs remained divided between the two, see Onésimo Díaz Hernández, La "Ley del Candado" en Alava, [in:] Sancho el Sabio 11 (1999), pp. 151-2

- ^ Díaz Hernández 1999, p. 152

- ^ La Epoca 01.05.10, available here

- ^ La Epoca 09.03.14, available here; Amézola was the 1900 Olympic pelota champion (the only one in history, since pelota was later withdrawn from the olympic games), see olimpismo blog available here

- ^ El Heraldo de Madrid 09.03.14, available here

- ^ in 1918, Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ the address was delivered in castellano, Javier G. Chamorro, Bitarte: humanidades e historia del conflicto vasco-navarro : fueros, constitución y autodeterminación, Donostia 2009, ISBN 8461307119, 9788461307111, p. 209

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ El Imparcial 16.05.28, available here

- ^ in 1920, ABC 24.09.70

- ^ see the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ see Cortes service here, see also the official deputy certificate available here

- ^ "Esteban Bilbao planteó que sólo existía la escuela socialista, la liberal y la cristiana. Las dos primeras creaban desorganización al centrarse en el Estado o en el individuo. Por eso el orador subrayaba la importancia de la Religión la única que conseguía la unidad de la humanidad bajo la luz de la solidaridad, y el problema social es principalmente un problema de solidaridad", Orella Martínez 2012, p. 223

- ^ Orella Martínez 2012, p. 223

- ^ Stanley G. Payne, The Franco Regime, Madison 2011, ISBN 0299110745, 978-0299110741, p. 235

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ Entrevista a Esteban Bilbao, [in:] Esfuerzo común 102 (1969)

- ^ Orella Martínez 2012, p. 223

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ see the official Senate service available here

- ^ see the official Cortes service available here

- ^ ABC 13.03.1923

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ Josep Carlos Clemente, Carlos Hugo: La Transición Política Del Carlismo: Documentos, 1955-1980, Madrid 2000, ISBN 9788480100786, p. 33, Orella Martínez 2012, p. 223

- ^ Díaz Díaz 1980, p. 591, see also Guía oficial de España 1927, p. 661, available here

- ^ Esteban Bilbao Eguia entry [in:] Concierto economico website, available here Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online, also Entrevista a Esteban Bilbao, [in:] Esfuerzo común 102 (1969)

- ^ see Cortes service here

- ^ Don Jaime had no problem with dictatorial nature of Primo's regime; he despised it when realized that Primo intended to support the Alfonsine monarchy. This led some authors to conclude that by accepting primoderiverista posts, Bilbao betrayed Carlism and moved to the Alfonsine camp, see José Carlos Clemente Muñoz, El carlismo en el novecientos español (1876-1936), Madrid 1999, ISBN 8483741539, 9788483741535, p. 168, the charge repeated also in Carlist propaganda of the 1950s

- ^ Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521207294, 9780521086349, p. 72; some sources suggest that Bilbao sympathised with the Mellists already during their secession, see Manuel Martorell-Perez, Nuevas aportaciones históricas a la evolución ideológica del carlismo, [in:] Gerónimo de Uztariz, 16 (2000), p. 104

- ^ the post he retained until 1933, Juan José Alzugaray Aguirre, Vascos relevantes del siglo XX, Donostia 2004, ISBN 9788474907339, p. 71

- ^ in 1930; Santiago Martínez Sánchez, El Cardenal Pedro Segura y Sáenz (1880-1957) [PhD thesis Universidad de Navarra], Pamplona 2002, p. 168

- ^ Martínez Sánchez 2002, p. 129

- ^ Robles, Robles Muñoz 1997, p. 415

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 72

- ^ Eduardo Gonzales Calleja, Contrarrevolucionarios, Madrid 2011, ISBN 9788420664552, p. 66; some consider it a reference to the Soviet Russia, some to the exiled Alfonso XIII

- ^ Galindo Herrero, Los partidos, Madrid 1954, Blinkhorn 2008, pp. 85, 324-5

- ^ Sánchez Erauski 1994, p. 213

- ^ Julio Aróstegui, Eduardo Calleja, La tradición recuperada: El requeté carlista y la insurrección, [in:] Historia Contemporanea 11 (1994), p. 35

- ^ Entrevista a Esteban Bilbao, [in:] Esfuerzo común 102 (1969), Gonzales Calleja 2011, p. 77

- ^ Gonzales Calleja 2011, p. 77

- ^ Aróstegui, Calleja 1994, pp. 35-66

- ^ Carlos Pulpillo Leiva, Orígenes del franquismo: la construcción de la "Nueva España" (1936–1941), [PhD thesis Universidad Rey Juan Carlos], Madrid 2013, p. 169

- ^ Maximiliano Garcia Venero, Historia de la Unificacion, Madrid 1970, p. 72

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 190

- ^ Gonzales Calleja 2011, pp. 69-70

- ^ ABC 17.11.31 available here

- ^ Josep Carlos Clemente, Breve historia de las guerras carlistas, Madrid 2011, ISBN 8499671705, p. 231, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 77; some sources claim the exile lasted 3 months, see ABC 24.09.70

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 88

- ^ Clemente 2011, p. 231, ABC 24.09.70

- ^ see Cortes service here

- ^ Beatriz Aizpun Bobadilla, La reposición de la Diputación Foral de Navarra, enero 1935, [in:] Principe de Viana 10 (1988), p. 18

- ^ Joaquín Monserrat Cavaller, Joaquín Bau Nolla y la restauración de la Monarquía, Madrid 2001, ISBN 8487863949, p. 54

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 208

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 215

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 204

- ^ Clemente 2011, p. 231

- ^ ABC 24.09.70

- ^ picturesque details of the exchange available here

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ Jaime Ignacio del Burgo Tajadura, Un episodio poco conocido de la guerra civil española. La Real Academia Militar de Requetés y el Destierro de Fal Conde, [in:] Principe de Viana 196 (1992), p. 492

- ^ Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936-1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 8487863523, 9788487863523, p. 238

- ^ Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis in Historia Contemporanea, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Valencia 2009, p. 30

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2009, pp. 30-31

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 126

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 31

- ^ jointly with Rodezno, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 259; the name of the body is given as "Selección Política", which is probably a typo and should read "Sección Política"

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ the 4 Carlists were conde Rodezno, Tomás Dolz de Espejo, Luis Arellano and José María Mazón, Mercedes Peñalba Sotorrío, Entre la boina roja y la camisa azul, Estella 2013, ISBN 9788423533657, pp. 51-2

- ^ Sánchez Erauski 1994, p. 213, Blinkhorn 2008, pp. 293, 361

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 187

- ^ Josep Carles Clemente, Historia del Carlismo Contemporaneo 1935-1972, Barcelona 1977, ISBN 8425307597, 8425307600, p. 125, Clemente 2011, p. 231; according to Fal Conde, Bilbao and others "han prestado colaboración en cargos políticos destacados, no sólo sin autorización de la jerarquía sino abiertamente en contra de la orientación de la Comunión", quoted after Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 187

- ^ Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, pp. 77-86

- ^ Paul H. Lewis, Latin Fascist Elites: The Mussolini, Franco, and Salazar Regimes, London 2002, ISBN 0313013349, 9780313013348, p. 85

- ^ in Bilbao, San Sebastián or Tolosa; they could have been political gatherings, military events like recruits taking the oath, or religious, like consagración de Vizcaya al Sagrado Corazón de Jesús, see Sánchez Erauski 1994, p. 213

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online; others identify the body as Comisión de Códigos, see Díaz Díaz 1980, p. 591

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ During early Francoism some 1% of the population went through jails and some 1,1‰ were judicially executed. Comparative background might be provided by similar European post-civil-war cases. In Poland (until 1953) there were 250,000 political prisoners, ca. 1% of the population, Tomasz Łabuszewski (ed.), Śladami zbrodni. Projekt edukacyjny IPN, Warszawa 2007, p. 6. Military tribunals, dealing with crimes against state, sentenced at least 5,800 to death. The number of those executed remains obscure and is estimated at few thousand, 0,2-0,3‰ of the population, Dariusz Burczyk, Igor Hałagida, Alicja Paczoska-Hauke (eds.) Skazani na karę śmierci przez Wojskowe Sądy Rejonowe w Bydgoszczy, Gdańsku i Koszalinie (1946-1955), Gdańsk 2009, ISBN 9788376290553, pp. 9, 17. In Greece there were 65,000 political prisoners, some 0,9% of the population, Minas Samatas, Greek McCarthyism: a comparative assessment of Greek post-civil war repressive anticommunism and the U.S. Truman-McCarthy era, [in:] Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora 13 (1986), p. 38. In 1949 the Athens government admitted 3,150 death sentences for contributing to the revolt; at least 1,233 have actually been executed, some 0,2‰ of the population, Bickham Sweet-Escott, Greece: A Political and Economic Survey 1939-1953, London 1954, p. 73, though some authors claim there were 5,000 executed by court-martial, which would constitute 0,7‰ of the population, Stanley G. Payne, Civil War in Europe, 1905-1949, Cambridge 2011, ISBN 9781107648159, p. 223. In both Polish and Greek cases numbers do not include death sentences on theoretically non-political charges, extrajudicial executions and – in case of Greece – death due to atrocious conditions in labor camps. In long-established democracies which experienced minor fratricidal violence, by no means comparable to a civil war, the number of politically-motivated death penalties administered by the judicial system was not negligible. In case of post-1944 Belgium there were 2,940 Nazi collaborators (some 0,4‰ of the population) sentenced to death, though the number of those actually executed was 242, Payne 2011, p. 204

- ^ official number of judicial executions during Stalinism only was 0.8m, see Stephen G. Wheatcroft, Victims of Stalinism and the Soviet Secret Police: The Comparability and Reliability of the Archival Data. Not the Last Word, [in:] Europe-Asia Studies 51/2 (1999), pp. 315–345. In Nazi Germany the number of judicial executions was relatively low; the notorious Volksgerichtshof court administered 5,2 thousand death penalties, see Alan E. Steinweis, The Law in Nazi Germany: Ideology, Opportunism, and the Perversion of Justice, Vermont 2015, ISBN 9780857457806, 0857457802, p. 65, though total number of deaths inflicted upon own citizens was much higher; the eugenics program alone produced extermination of at least 70,000 people, see Ernst Klee, Dokumente zur Euthanasie, Frankfurt a/M 1985, ISBN 3596243270, p. 232, not to mention exterminated German Jews, Germans who perished in concentration camps and victims of non-judicial terror

- ^ Stanley G. Payne, The Spanish Civil War, Cambridge 2012, ISBN 9781107002265, p. 245

- ^ in the Francoist Spain there was no death penalty for political crimes as such; most charges featured a flexibly applied category of violence, Payne 2012, pp. 223-4

- ^ Payne 2011, pp. 222-223, Payne 2012, p. 246

- ^ Payne 2011, p. 227

- ^ excluding those in labour battalions, military prisons or those incarcerated as common criminals, Paul Preston, The Spanish Civil War. Reaction, revolution and revenge, London 2006, ISBN 9780007232079, p. 527, Payne 2011, p. 223

- ^ there are 4,663 casualties listed for the 1939-1945 period, Julian Casanova, Francisco Espinosa Maestre, Conxita Mir, Francisco Moreno Gómez, Morir, matar, sobrevivir: la violencia en la dictadura de Franco, Barcelona 2004, ISBN 8484325067, 9788484325062, p. 20

- ^ Antony Beevor, The Battle for Spain; The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939, London 2006, ISBN 9780143037651, p.404, Preston 2006, p. 313

- ^ George Packer, The Spanish Prisoner, [in:] The New Yorker 31.10.05, available here

- ^ the law envisioned a fairly totalitarian structure, with alcalde, local Falange leader, local parochial priest and local Guardia Civil commander in-built into the control system; Bilbao contributed as head of codification commission, since the law was adopted in February 1939, before he assumed the ministry, Casanova, Espinosa, Mir, Moreno 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Casanova, Espinosa, Mir, Moreno 2004, p. 23

- ^ Casanova, Espinosa, Mir, Moreno 2004, p. 20

- ^ Helen Graham, The Spanish Civil War. A Very Short Introduction, Oxford 2005, ISBN 978-0192803771, p.134

- ^ Beevor 2006, p.407

- ^ Casanova, Espinosa, Mir, Moreno 2004, p. 27

- ^ Aurora G. Morcillo, The Seduction of Modern Spain: The Female Body and the Francoist Body Politic, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-8387-5753-6, p. 94

- ^ Graham 2005, p. 134

- ^ as a Francoist dignitary Bilbao used to spend summer breaks in his home in Durango. According to an anecdote, during the visit to a local barber he was approached by an old local acquaintance, who asked: "Hi Esteban, nun dittuk defenditzen izan doguzan fueruak? " (Esteban, what happened to the fueros we used to defend?). The minister ignored the question. Referred after José Luis Lizundia, De los nuevos "maeztus", [in:] El Pais 18.03.06, available here

- ^ according to his own account, Bilbao objected to the designs of Minister of Economy during the government sitting and Franco adhered to his point of view, Entrevista a Esteban Bilbao, [in:] Esfuerzo común 102 (1969)

- ^ "where he was even more useful to Franco", Lewis 2002, p. 89

- ^ see Cortes service here

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ Entrevista a Esteban Bilbao, [in:] Esfuerzo común 102 (1969)

- ^ along Antonio Iturmendi and Joaquín Bau

- ^ no systematic data is available. The longest ever serving MP identified was Práxedes Mateo Sagasta, who served more than 40 years

- ^ shared with Sagasta, who served between 1854 and 1903. Bilbao's role of a parliamentary icon remains somewhat odd, given his confessed "hatred of parliamentarism", Blinkhorn 2008, p. 204

- ^ Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, El naufragio de las ortodoxias. El carlismo, 1962-1977, Pamplona 1997; ISBN 9788431315641, 9788431315641, p. 12

- ^ Payne 2011, p. 373

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ Payne 2011, p. 372

- ^ between 18th and 27th of October, 1949; Franco at that time visited Portugal. He used to leave mainland Spain on other occasions, but always for Spanish-held territories, like during his visit to Ifni and Sahara in October 1950

- ^ Lewis 2002, p. 85; some authors observe sarcastically that Bilbao was among those who "had not let their Carlism get in the way of their careers", Jeremy MacClancy, The Decline of Carlism, Reno 2000, ISBN 9780874173444, p. 93

- ^ in street-talk mocked as "Francisco Franco, Caudillo de España por una gracia de Dios" (caudillo by the joke of God), Payne 2011, p. 235

- ^ Payne 2011, p. 260

- ^ Paul Preston, Franco. A biography, London 2011, ISBN 9780006862109, p. 466

- ^ he demanded legal action against perpetrators, their expulsion from FET, and creation of a government "of authority to rectify the errors of the past" – a veiled demand of a monarchist cabinet, Preston 2011, p. 467

- ^ Preston 2011, p. 468; Lewis 2002, p. 88 presents a slightly different view claiming that Bilbao was satisfied with the government changes, as they loosened the Falangist grip on power

- ^ Preston 2011, pp. 469 and onwards

- ^ Preston 2011, p. 662

- ^ Entrevista a Esteban Bilbao, [in:] Esfuerzo común 102 (1969)

- ^ Entrevista a Esteban Bilbao, [in:] Esfuerzo común 102 (1969)

- ^ Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, pp. 90, 143

- ^ "traidor a D. Jaime, desleal a la Regencia, puntal del actual régimen, ha sido uno de los iniciadores de la disidencia 'octavista'. No vacilamos en vaticinarlo: ni permanecerá en las filas del que llaman Carlos VIII, ni llevará a éste al triunfo. Don Esteban, igual que los que le siguen, consecuente en su deslealtad política, seguirá a las órdenes de Franco mientras éste gobierne, y luego ya buscará la manera de ponerse a las del que haya de gobernar" – quoted after Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 187

- ^ e.g. in 1948; Carlist girls from the Margaritas organization, when on tour visiting the Cortes, demonstrated their utter disrespect to Bilbao (no details known), Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 188

- ^ he did not sign Acto de Estoril, Clemente 1977, p. 299

- ^ this candidature was unofficially promoted by the so-called Carlist "cruzadistas" already in the mid-1930s

- ^ Iker Cantabrana Morras, Lo viejo y lo nuevo: Díputación-FET de las JONS. La convulsa dinámica política de la "leal" Alava (Segunda parte: 1938-1943), [in:] Sancho el Sabio 22 (2005), ISSN 1131-5350, p. 158

- ^ Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El final de una ilusión. Auge y declive del tradicionalismo carlista (1957-1967), Madrid 2016, ISBN 9788416558407, p. 87

- ^ José Carlos Clemente, Seis estudios sobre el carlismo, Madrid 1999, p. 24, Cantabrana Morras 2005, p. 158

- ^ e.g. in 1962 they requested and obtained for Carlos Hugo his formal reception by Bilbao, taken advantage of propagandawise later on, Vázquez de Prada 2016, p. 157

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2009, pp. 187, 380

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 463

- ^ MacClancy 2000, p. 153, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 430. Bilbao sent at least another telegram, this time as a private person, in 1968; it remains a curiosity that the same year similar greetings were sent by the PCE leader, Santiago Carrillo, MacClancy 2000, p. 175;

- ^ Entrevista a Esteban Bilbao, [in:] Esfuerzo común 102 (1969). However, the same year Bilbao used to give more ambiguous answers. When asked by El Correo Catalan whether he was a Javierista, Bilbao replied: "I am a Carlist, I was and I will be. A king? I am faithful to the Dios, Patria, Rey ideario, and my king is the one who serves Fatherland and God. My king will be a Catholic prince, Spanish, over 30 years.. like specified in Ley de Sucesion", quoted after Ramón María Rodon Guinjoan, Invierno, primavera y otoño del carlismo (1939-1976) [PhD thesis Universitat Abat Oliba CEU], Barcelona 2015, p. 435

- ^ Entrevista a Esteban Bilbao, [in:] Esfuerzo común 102 (1969)

- ^ ABC 26.09.70, available here

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ Díaz Díaz 1980, p. 591

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ Díaz Díaz 1980, p. 591

- ^ Orella Martínez 2012, p. 223

- ^ Alzugaray, Alzugaray Aguirre 2004, p. 71

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ ABC 24.09.70

- ^ Díaz Díaz 1980, p. 591

- ^ Estornés Zubizarreta, Esteban Bilbao Eguía entry at Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ^ Pulpillo Leiva 2013, p. 830

- ^ ABC 24.09.70

- ^ Boletin Oficial del Estado 02.10.61, available here

- ^ Boletin Oficial del Estado 07.08.72, available here

- ^ see Juzgado Central de Instrucción No 005, Audiencia Nacióñal, Auto 16.10.08, available here Archived 2012-10-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alzugaray, Alzugaray Aguirre 2004, p. 71

- ^ Sánchez Erauski 1994, p. 213

- ^ Josu Erkoreka, De la madre Maravillas a don Esteban Bilbao Eguia, [in:] josuerkoreka blog 12.12.08, available here

- ^ Dieciocho de Julio, [in:] Ahaztuak 1936-1977 blog 18.07.08, available here

- ^ see Comunicado de Izquierda Republicana sobre la retirada del busto de Manuel Azaña, [in:] Izquierda Republicana service 14.06.12, available here Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine; the portrait in question is also on the Cortes web site here

- ^ compare María Cruz Rubio Liniers, María Talavera Díaz, Bibliografías de Historia de España, vol. XIII: El carlismo, Madrid 2012, ISBN 8400090136, 9788400090135

Further reading

- Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 1975, ISBN 9780521207294

- Julian Casanova, Francisco Espinosa Maestre, Conxita Mir, Francisco Moreno Gómez, Morir, matar, sobrevivir: la violencia en la dictadura de Franco, Barcelona 2004, ISBN 8484325067, 9788484325062

External links

- Bilbao's birth certificate

- Bilbao at official Cortes service

- Bilbao at Basque encyclopaedia

- crime against humanity charge

- Memoria Histórica site dedicated to the victims of Francoism

- Bilbao's speech in the Cortes (1946) video

- Bilbao handing over to Iturmendi (1965) video

- Bilbao's obituary

- Vizcainos! Por Dios y por España; contemporary Carlist propaganda on YouTube