Contents

Fort Mifflin, originally called Fort Island Battery and also known as Mud Island Fort, was commissioned in 1771 and sits on Mud Island (or Deep Water Island) on the Delaware River below Philadelphia, Pennsylvania[nb 1] near Philadelphia International Airport.

During the American Revolutionary War, the British Army bombarded and captured the fort as part of their conquest of Philadelphia in autumn 1777. In 1795, the fort was renamed for Thomas Mifflin, a Continental Army officer and the first post-independence Pennsylvania governor.[3]

The U.S. Army began rebuilding the fort in 1794, and continued to garrison and build on the site into the 19th century. Fort Mifflin housed prisoners during the American Civil War. The U.S. Army decommissioned Fort Mifflin for active duty infantry and artillery in 1962.

While the older portion of the fort was returned to the City of Philadelphia, a portion of the fort's grounds are still actively used by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, making it the oldest fort in use by the U.S. military. Historic preservationists have restored the fort, which has been named a National Historic Landmark.

History

Colonial defense of Philadelphia

Built in 1681 in Philadelphia near the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, Fort Mifflin was recognized as strategically important because of the role it played in defense of the settlement.[4] However, William Penn, a Quaker with religious objections to military life, left Philadelphia undefended. When European colonists established permanent settlements, they also traditionally provided protection of those settlements, but Quakers founded the only significant European settlements without any such fortifications.[5] Since the Quakers rejected the military, they instead sought to make peace with Native American tribes in the area and avoid any need to fortify their settlements militarily. While other colonies suffered from conflict and warfare, Philadelphia prospered.

By the 1740s, Fort Mifflin ranked as the richest British port in the New World. French and Spanish privateers then entered the Delaware River, threatening the city. During King George's War between 1744 and 1748, Benjamin Franklin raised a militia because the legislators of the city, most of whom were Quakers, were opposed to military engagement and refused to defend Philadelphia "either by erecting fortifications or building Ships of War". Franklin raised money to create earthwork defenses and to buy artillery.[6]

At the end of the war, commanders disbanded the militia and left derelict the defenses of the city.[7] With renewed colonial warfare in the 1750s, especially the French and Indian War, plans were drawn up for a fort on Mud Island, but no fort was built.[8] Only in the 1770s did the city acquire permanent fortifications.

By 1771, Philadelphia ranked as the largest British port and dockyard in North America. Locals then rose in protest against British economic policies and imports. In response to complaints by the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Pennsylvania governor John Penn asked General Thomas Gage to send someone capable of designing defenses for the city. He intended to have a fort on Mud Island that would help regulate traffic entering and exiting the port.[8] Gage assigned Captain John Montresor of the British Corps of Engineers to the task. Montresor presented six designs to Penn and the Board of Commissioners; the board proposed constructing a fort on Mud Island (also known as Deep Water Island).[9][nb 2]

The commissioners reviewed the plans, found them all too expensive, and insisted on economy despite Montresor's protestations about the budget.[10] Montresor stated that his preferred plan cost about £40,000 and that he intended to mount "32 pieces of cannon, 4 mortars and 4 royal howitzers ... which at 6 men each make 240 men required, 160 musketry, in all 400 garrison."[10] The colonial Provincial Assembly passed a bill releasing £15,000 for the construction of the fort and the purchase of Mud Island from Joseph Galloway, the Speaker of the House.[11] The board instructed Montresor to begin construction but failed to provide him with the funds that he considered necessary to do so properly.

The rooms in the farthest interior of "Casemate #11" probably date from the original construction in 1771. On 4 June 1772, Montresor left the head workman in charge of the construction project and returned to New York disgruntled. The project floundered onward for about a year, when it stopped for lack of guidance and funding.[12] The crews completed only the east and south walls, built in stone.[13]

American Revolutionary War

Following the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, Benjamin Franklin headed a committee to provide for the defense of the revolutionary capital of Philadelphia. The Philadelphia Committee of Public Safety soon restarted construction on the fort and finally completed it in 1776.

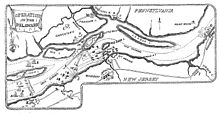

The committee simultaneously also built Fort Mercer in New Jersey, on the eastern bank of the Delaware River across from Fort Mifflin.[14] The Americans intended to use Fort Mifflin and Fort Mercer to control the activity of the British Navy on the Delaware River, guarding against General Howe and Admiral Reynolds' advance naval fleet on the Delaware.[15]

Defenders of Philadelphia assembled chevaux de frise obstacles,[14] placed in tiers spanning the width of the Delaware between Forts Mercer and Mifflin. These defenses comprised wooden-framed "boxes", 30 feet square, constructed of huge timbers and lined with pine planks. Defenders lowered these frames onto the riverbed and filled each with 20 to 40 tons of stone to anchor it in place. They placed two or three large timbers tipped with iron spikes into each frame, set underwater and facing obliquely downstream. They then chained the boxes together to maintain continuity. The chevaux de frise presented a formidable obstacle that could impale unwitting ships. The system's design included gaps to allow passage of friendly shipping. Only a select few patriot navigators knew the locations of safe passage through this barrier. Soldiers at Forts Mercer and Mifflin could fire at anyone attempting to dismantle these obstacles. Similar obstacles were built downriver at Fort Billingsport, New Jersey, but that area fell to the British on October 2, 1777.[16]

After Washington's defeat at the Battle of Brandywine, the British took control of Philadelphia in September 1777 during their Philadelphia campaign. The British forces then laid siege to Fort Mifflin and Fort Mercer in early October 1777, unsuccessfully attacking the latter by land and river in the Battle of Red Bank on October 22.[17] The British Army intended the siege to open up its supply line via the Delaware River.[14] Captain John Montresor, earlier designer and constructor of Fort Mifflin, planned and built the siege works used against Fort Mifflin.[12] He then led the siege and destroyed much of the fort.[14] During the siege, four hundred American soldiers held off more than two thousand British troops and 250 ships until November 10, 1777, when the British intensified their assault, launching an incessant barrage of cannonballs into the fort.[14] Among those stationed at the fort was private Joseph Plumb Martin, who later wrote an account of the battle.

Defending the riverway Commodore John Hazelwood with a sizable fleet of galleys, sloops, and fire-vessels launched several raids on British positions on shore, constantly harassing British river operations while patrolling the waters around the fort. On November 15, 1777, the American troops evacuated the fort. Their stand effectively denied the British Navy free use of the Delaware River and allowed the successful repositioning of the Continental Army for the Battle of White Marsh and subsequent withdrawal to Valley Forge.[14] Fort Mifflin experienced the heaviest bombardment of the American Revolutionary War. The siege left 250 of the 406 to 450 men garrisoned at the Fort Mifflin killed or wounded.[18] Comrades-in-arms ferried these dead and wounded to the mainland before the final evacuation.[19] Fort Mifflin never again saw military action.[15]

Of the original Fort Mifflin, only the white stone walls of the fort survive today. The pockmarks in these stone walls evidence the intensity of the British bombardment of 1777. Local residents know this siege and massive bombardment as the Battle of Mud Island.

Reconstruction during War of 1812

The ruins of Fort Mifflin lay derelict until 1793, when rebuilding began under what was later called the first system of U.S. coastal fortifications. In 1794, Pierre L'Enfant, also responsible for planning Washington, D.C., supervised the reconstruction, including the design and rebuilding of the fort. Reconstruction work began on the fort in 1795, under the auspices of engineer officer Louis de Tousard, who from 1795 to 1800 traveled along the coast between Massachusetts and the Carolinas working on coastal defenses.[20] The initial goal was to rebuild the fort to accommodate 48 guns.[21] The army probably built the outer room of "Casemate #11" during the reconstruction of the fort from 1794 through 1798 and used it as a "proof room" to make cannon charges. The buildings at Fort Mifflin included barracks for soldiers in the 1790s, measuring 117 feet (36 m) by 28 feet (8.5 m) and consisting of two stories. The original barracks contained seven rooms, five of them each designed to house 25 men. The army officially named the fort after Thomas Mifflin, a Continental Army officer and the first post-independence Governor of Pennsylvania, in 1795.[3][22] Rebuilding the fort consumed $94,000 of a total fort budget of $278,000 in 1798 and 1799 alone (in 1799 money).[23] Also, the US Congress met in Philadelphia until 1800 and Fort Mifflin was well garrisoned until then, usually with two companies.[24]

Over a cross-shaped hole in the ground previously designated as a last-ditch defensive area near the center of the fort, the army built the extant citadel structure to house the commandant in 1796. Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Rochefontaine replaced Pierre Charles L'Enfant as chief engineer at Fort Mifflin in 1798 and completed the citadel structure to house the commandant. Lieutenant Colonel Rochfontaine used and improved original designs of L'Enfant. The Commandant's House exemplifies Greek Revival architecture, rare on Army installations in the United States. The army also built the six cavelike casemates as defensive structures in the case of an enemy siege during the reconstruction of 1798–1801. Soldiers used a "bake oven" just inside the main gate and the entrance to the bomb-proof casemate for baking bread, as a chapel, and as a mess hall. The army designed the largest casemate (#1) as a barracks. The three smaller casemates were used for storage. The architects intended Casemate #5, about half the size of Casemate #1, as the headquarters of Fort Mifflin in the time of attack.

The army built the blacksmith shop before 1802; it is probably the oldest surviving complete structure at Fort Mifflin.[25] In 1814, a two-story officers' quarters, measuring 96 feet (29 m) by 28 feet (8.5 m), was built.[26]

In the 1811 annual report of the secretary of war, Fort Mifflin was described as "...mounting 29 heavy guns, with a water battery without (outside) the works, mounting 8 heavy guns... with brick barracks for 100; within 3/4 of a mile... (is) the Lazaretto, which are good barracks for 400 men."[27]

Pre-Civil War period

The U.S. Army built a one-story brick structure, 24 feet (7.3 m) by 44 feet (13 m), in 1815–1816 as a guardhouse and prison. Around 1819, north of the walls of the fort, the army also built a building used as a hospital (2nd floor) and mess hall (ground floor).

After the construction of Fort Delaware in 1820, Fort Mifflin was relegated to secondary status. During the 19th century the area around the fort was drained and filled until Mud Island connected with the western bank of the Delaware River.[15] Nevertheless, the building and garrisoning of Fort Mifflin continued. In the early 1820s, the army began meteorological observations at the fort.

The soldiers' barracks building was extensively renovated in 1836, along with the officers' quarters. At a later date the soldiers' barracks was again renovated, at which time the roofline was changed to add the second floor. (HABS # PA-1225E). In 1837, the hospital and mess hall building was converted to a meetinghouse[28] and an artillery shed, for the storage and protection of cannon, was built on an interior raised platform.[29]

By 1839, the army designated the one-story brick guardhouse-prison as an arsenal.[30] On December 27, 1842 the army completed a brick, one-story sutler building/storehouse measuring 55 feet (17 m) by 20 feet (6.1 m).[31]

During the 1840s, a two-story kitchen wing was added to the officers' quarters building.

American Civil War

During the Civil War, the Union used Fort Mifflin to house Confederate prisoners of war, as well as Union soldiers and civilian prisoners. Numerous Confederate prisoners occupied Fort Mifflin from 1863 to 1865 and were housed in Casemate #1. The Union Army used three smaller casemates to hold political prisoners during the same period. Various people wrote graffiti inside the cell doors and on the inner walls of "Casement #11" during the 1860s. They also left a wine token and penny, both dated 1864 and in remarkable condition.

The Union Army accused William H. Howe, one of its soldiers, of desertion, found him guilty of murder, and imprisoned him famously at Fort Mifflin from January 1864. Howe led an attempted escape of two hundred[32] prisoners from Casemate #5 in February 1864. Afterwards, Howe was housed in a solitary confinement cell in Casemate #11, where he left his signature. Despite his illiterate reputation, Howe twice wrote letters (filled with bad grammar and run-on sentences) to President Abraham Lincoln asking for clemency, signing them with his own hand. In April 1864, Howe was transferred to Eastern State Penitentiary but, on 26 August of the same year, was transferred back to Fort Mifflin. The condemned prisoner was briefly held in the fort's wooden guardhouse prior to his execution on the gallows, which were steps away from the guardhouse. Howe's hanging was before an audience of persons who paid for tickets to watch the execution. Of the three other men executed at Fort Mifflin, none had a paid public audience.[33]

The army proposed adding a sally port on the west side in 1864.

On November 24, 1864, the Union Army sent Lieutenant Colonel Seth Eastman, the American Western frontier painter, to Fort Mifflin to supervise the discharge of all civilian and military prisoners, then numbering more than two hundred. On January 2, 1865, Eastman reported that his garrison consisted of B Company, 186th Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment, a detachment of recruits, and the hospital staff.

After the Civil War

On August 20, 1865, Captain Thomas E. Merritt with A Company, 7th United States Veteran Volunteers, relieved Lieutenant Colonel Eastman. The army completed the west sally port by 1866.[34] In 1866, the 7th USVV vacated the fort and the District Engineer Office, Corps of Engineers, replaced the company. The fort passed in and out of use several times in its subsequent history.[3]

Between 1866 and 1876, the Corps of Engineers intermittently repaired and modernized Fort Mifflin and upgraded its armament. The army worked on the detached high battery south of the fort from 1870 to 1875 but never finished it. The army built a torpedo (underwater mine) casemate in 1874–1875; its entrance sealed off access to the unused magazine, "Casemate #11", preserving a trove of historical artifacts. These artifacts include pottery, a tin cup, a tin chamber pot, period buttons, and dozens of animal bones. The 1875 Annual Report, "The construction of the torpedo casemate has commenced," notes the east magazine torpedo casemate. The army constructed this casemate in 1876.

From 1876 to 1884, the Philadelphia District Office of the Corps of Engineers took custodial responsibility of Fort Mifflin. The east magazine (torpedo casemate) first appears on a map in 1886.[35] During World War I the fort was used to store munitions.[3]

The army removed the two-story kitchen wings from the officers' quarters building sometime before the 1920s.[36] They were restored in the early 1990s in a major restoration of the building.

In 1923, the Marine Barracks held the first recorded USMC Birthday dance.[37]

World War II

During World War II, the U.S. Army stationed anti-aircraft guns at Fort Mifflin to defend the nearby Fort Mifflin Naval Ammunition Storage Depot (NASD) and the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard. Marine Corps units from the naval shipyard guarded the Naval Ammunition Storage Depot at the northern end of the former Mud and Cabin Islands, and the U.S. Army assigned troops to defend the fort. In April 1942, the U.S. Army stationed Battery H of the 76th Coast Artillery Regiment (Antiaircraft) (Semimobile) (Colored),[38] the first African-American Coast Artillery unit in U.S. military history, at the fort.[nb 3] On May 24, 1942, the 76th Regiment was relieved and moved to California to prepare for overseas deployment; the U.S. Army then stationed the 601st Coast Artillery Regiment (Antiaircraft) (Semimobile) at Fort Mifflin.[39]

Post-war renovations

In 1954, Fort Mifflin was decommissioned as an active military post. Several documents reference an old magazine entrance in the location of Casemate #11, and the number 11 comes from a 1954 map associated with the old magazine entrance. Fort Mifflin closed, ranking among the oldest forts in continuous use in the nation's history. The fort's interior was renovated in 1960. In the 1980s, Harold Finigan, then executive director of the fort, renovated its exterior.

Decommissioning and restoration

In 1962, the federal government deeded Fort Mifflin to the City of Philadelphia.[14] In 1969, architect John Dickey was responsible for restoring the Blacksmith Shop's bellows and forge.

Fort Mifflin is still an active base for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and is currently the oldest active U.S. military base and the only base in use that predates the Declaration of Independence.

In the late 1970s, the Commandant's House at the Fort was destroyed by an accidental fire started by camping Boy Scouts.[40]

In the 1980s and early 1990s, Harold Finigan, the fort's executive director, worked with architects John Dickey and John Milner to restore the fort's artillery shed, hospital, mess hall, officers' quarters, kitchen wings, arsenal, soldiers' barracks, and north and west sally ports and seawall, and to construct a bridge over the moat at the fort's main gate. During restoration, it was determined that the exterior of the buildings had been yellow washed during Civil War era.[41]

In 2006, Wayne Irby rediscovered and unearthed the recently named Casemate #11 at Fort Mifflin. In August 2006, Dr. Don Johnson and a small group of volunteers uncovered and rediscovered the complexity of the fort's inner rooms and a trove of historical artifacts inside Casemate #11.

Standing buildings

- Arsenal

- Artillery Shed

- Blacksmith Shop

- Sutler Building/Storehouse

- Soldiers' Barracks

- Officers Quarters

- Commandant's House

- Hospital/Messhall

- West Sallyport

- Casemates

- East Magazine

- Casemate #11

See also

- Eastwick

- Frankford Arsenal

- Harbor Defenses of the Delaware

- List of coastal fortifications of the United States

- List of forts

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Philadelphia

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Southwest Philadelphia

- Philadelphia International Airport

- Philadelphia Lazaretto

- Schuylkill Arsenal

- Seacoast defense in the United States

References

- Explanatory notes

- ^ The island's back channel has since been filled in.

- ^ The details for the six different designs can be found at the David Library; "Montresor Papers" catalogued by Harold Finigan.

- ^ The oral history of one of these soldiers, Mr. Isaac Wright, has been preserved in the Ralph J. Bunche Oral History Collection (RJB #665) at Howard University.

- Citations

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "PHMC Historical Markers". Historical Marker Database. Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Roberts 1988, pp. 686–687.

- ^ Dorwart 1998, p. 7.

- ^ Dorwart 1998, p. 9.

- ^ Dorwart 1998, pp. 9–11.

- ^ Dorwart 1998, p. 12.

- ^ a b Dorwart 1998, p. 13.

- ^ Scull 1881, pp. 414–415.

- ^ a b Scull 1881, pp. 415–416.

- ^ Scull 1881, pp. 416–417.

- ^ a b Scull 1881, p. 417.

- ^ Liggett & Laumark 1979, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b c d e f g City of Philadelphia. "The History of Fort Mifflin, the Fort that saved America". Phila.gov. Archived from the original on February 8, 2014. Retrieved on 25 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Liggett & Laumark 1979, p. 41.

- ^ Roberts 1988, pp. 505–506.

- ^ Jackson 1986

- ^ Boatner 1966, p. 384.

- ^ "Olde Fort Mifflin Historical Society: A few facts about Fort Mifflin". Olde Fort Mifflin Historical Society. 2007. Archived from the original on November 1, 2008. Retrieved October 28, 2008. Retrieved on 28 October 2008.

- ^ Wilkinson 1960–1961, p. 179

- ^ Wade 2011, p. 17.

- ^ Dorwart 1998, p. 29.

- ^ Wade 2011, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Wade 2011, pp. 78–79, 87, 224–225.

- ^ (RG77 NAB)

- ^ (#475, RG 77, NAB)

- ^ Wade 2011, p. 244.

- ^ (ASP 7:632)

- ^ (As cited in a report from the Engineers Dept, 28 Nov 1837; American State Papers 7:580)

- ^ (Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) #PA1225.)

- ^ (Tompkins to Jessup, Consolidated Correspondence, Box 662, RG 92 NAB)

- ^ "Philadelphia Inquirer" February 26, 1864 "Excitement at Fort Mifflin"

- ^ Stop the Evil: A Civil War History of Desertion and Murder, by Robert I. Alotta, Presidio Press, 1996. Original from the University of Michigan. Digitized Sept. 19, 2008. ISBN 0-89141-018-X, 9780891410188, 202 pages

- ^ (B-566, RG 77, NAB)

- ^ (RG77, NAB)

- ^ (HABS #PA-1225F)

- ^ "USMC Birthday". Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ Stanton 1991, p. 463.

- ^ Stanton 1991, p. 474.

- ^ American State Papers 1:11

- ^ #41

Bibliography

- Boatner, Mark Mayo (1966). Cassell's Biographical Dictionary of the American War of Independence, 1763–1783. London: Cassell & Company. ISBN 0-304-29296-6.

- Dorwart, Jeffery (1998). Fort Mifflin of Philadelphia: An Illustrated History. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1644-8.

- Jackson, John (1986). Fort Mifflin: Valiant Defender of the Delaware. Old Fort Mifflin Historical Society Preservation Committee.

- Liggett, Barbara; Laumark, Sandra (1979). "The Counterfort at Fort Mifflin". Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology. 11 (1). Association for Preservation Technology International (APT): 37–74. doi:10.2307/1493677. JSTOR 1493677.

- Roberts, Robert B. (1988). Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: The Military, Pioneer, and Trading Posts of the United States. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-926880-X.

- Scull, G. D., ed. (1881). "The Montresor Journals". Collection for the Year 1881. Collections of the New-York Historical Society ... 1881. Publication fund series.[v. 14]. New York Historical Society.

- Stanton, Shelby L. (1991). World War II Order of Battle. Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-775-9.

- Wade, Arthur P. (2011). Artillerists and Engineers: The Beginnings of American Seacoast Fortifications, 1794–1815. CDSG Press. ISBN 978-0-9748167-2-2.

- Wilkinson, Norman B. (1960–1961). "The Forgotten "Founder" of West Point". Military Affairs. 24 (4). Society for Military History: 177–188. doi:10.2307/1984876. JSTOR 1984876.

Further reading

- Alotta, Robert I, "Old Fort Mifflin: The Chain of Command" Shackamaxon Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America 1977, 20 pages

- Alotta, Robert I, "The Spirit of the Men of Mifflin" Shackamaxon Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America 1971,

- Alotta, Robert I, "The Men of Mifflin" Shackamaxon Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America 1971

- Alotta, Robert I, "Old Fort Mifflin (1772-77 to 1972-77) Living History: A Meaningful Bicentennial" Shackamaxon Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America 1972 10 pages

- Alotta, Robert I, "Old Fort Mifflin: The Defenders" Shackamaxon Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America 1973

- Alotta, Robert I, "Old Fort Mifflin: The Buildings and Structures" Shackamaxon Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America 1973 36 pages

- Alotta, Robert I, "Historic Old Fort Mifflin" Shackamaxon Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America 1973

- Alotta, Robert I, "A Glossary of Fortification Terms as they relate to Old Fort Mifflin" Shackamaxon Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America 1972 12 pages

- Alotta, Robert I, "A Fort Mifflin Diary" Shackamaxon Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America 1973 36 pages

- Hardway, Ronald V., Benjamin Lemasters of Nicholas County, West Virginia : his ancestry, his war record, his descendants

- Jackson, John, The Pennsylvania Navy, 1775-1781 Rutgers University Press

- Martin, Joseph Plum, Private Yankee Doodle Western Acorn Press, 1962

- McGuire, Thomas J., The Philadelphia Campaign, Vol. II: Germantown and the Roads to Valley Forge, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pa., 2006. ISBN 978-0-8117-0206-5, pages 181 to 222.

- Selletti, Anthony L, Fort Mifflin: A Paranormal History, Selletti Press, Chester, Pa., 19013 October 2008, ISBN 0-615-22847-X, 9780615228471 248 pages

External links

- Fort Mifflin official website

- American History Fort Mifflin

- Fort Mifflin Historical Society

- Attack on Fort Mifflin

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) documentation:

- HABS No. PA-1225, "Fort Mifflin, Mud Island, Marine & Penrose Ferry Roads, Philadelphia, Philadelphia County, PA", 74 photos, 10 color transparencies, 9 measured drawings, 130 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HABS No. PA-1225-A, "Fort Mifflin, Guard House", 6 photos, 2 measured drawings, 6 data pages, supplemental material

- HABS No. PA-1225-B, "Fort Mifflin, Artillery Shed", 7 photos, 5 measured drawings, 6 data pages, supplemental material

- HABS No. PA-1225-C, "Fort Mifflin, Commandant's House (Headquarters)", 33 photos, 8 measured drawings, 12 data pages

- HABS No. PA-1225-D, "Fort Mifflin, Storehouse", 5 photos, 2 measured drawings, 5 data pages, supplemental material

- HABS No. PA-1225-E, "Fort Mifflin, Soldiers' Barracks", 16 photos, 5 measured drawings, 8 data pages

- HABS No. PA-1225-F, "Fort Mifflin, Officers' Quarters", 17 photos, 6 measured drawings, 8 data pages

- HABS No. PA-1225-G, "Fort Mifflin, Powder Magazine", 13 photos, 3 measured drawings, 9 data pages

- HABS No. PA-1225-H, "Fort Mifflin, Smith's Shop", 12 photos, 4 measured drawings, 6 data pages, supplemental material

- HABS No. PA-1225-I, "Fort Mifflin, Hospital", 4 photos, 6 measured drawings, 7 data pages

- HABS No. PA-1225-J, "Fort Mifflin, Frame Guard House", 1 photo, supplemental material