Contents

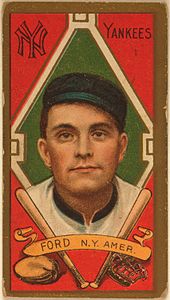

Russell William Ford (April 25, 1883 – January 24, 1960) was a Canadian-American professional baseball pitcher. He played in Major League Baseball for the New York Highlanders / Yankees of the American League from 1909 to 1913 and for the Buffalo Buffeds / Blues of the Federal League in 1914 and 1915. Ford is credited with developing the emery ball.

Born in Manitoba, Ford grew up in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where he began his baseball career. After he noticed how the ball moved after it was scuffed, he mastered how to doctor the baseball with a piece of emery paper hidden in his baseball glove. Using the pitch, Ford won 26 games in his rookie year with the Highlanders in 1910. After the pitch was outlawed in 1914, Ford's results declined, and his career ended in 1917. He is a member of the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame and the Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame and Museum.

Early life

Ford was born in Brandon, Manitoba, on April 25, 1883.[1] He was the third of five children born to Walter and Ida Ford. His mother was a second cousin of Grover Cleveland, who served as president of the United States. The Ford family moved to the United States when he was three years old,[2] and settled in Minneapolis, Minnesota when he was 10 years old.[2][3] He played sandlot ball in Minneapolis.[4]

Russ' older brother, Gene Ford, also played in the major leagues. Gene pitched in seven games for the Detroit Tigers in 1905. His younger brother, Walter, played in the minor leagues.[5]

Baseball career

Early career

Ford made his professional baseball debut in the Northern League with a team based in Enderlin, North Dakota, in 1904, but the team folded during the season. He continued playing in the 1904 season with a team in Lisbon, North Dakota.[6] After a recommendation by his older brother, Ford was signed by Bill Watkins, the manager of the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association, in July 1904.[7] In April 1905, Watkins sold him to the Springfield Senators of the Illinois–Indiana–Iowa League.[8] In 1906, he pitched for the Cedar Rapids Rabbits of the Illinois–Indiana–Iowa League.[9] At the end of the 1906 season, the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association drafted Ford from Cedar Rapids.[10]

In 1907, Ford discovered the emery ball, a pitch that was thrown with a ball that had been scuffed with a piece of emery. Ford came across the pitch by accident.[11] When warming up with catcher Ed Sweeney under a grandstand due to rain, Ford accidentally threw a ball into a wooden upright, marking the surface. Ford threw another pitch with the damaged ball, and noticed how it curved more than previous pitches.[12] He continued to study the effects of the rough patch on the wind resistance of the baseball when practicing, but did not yet begin to use it in a game.[13]

Ford returned to Atlanta for the 1908 season, and his pitching began to draw attention from major league teams.[14] The New York Highlanders of the American League purchased Ford from the Crackers.[15]

Major leagues

Ford made his major league debut for the Highlanders against the Boston Red Sox on April 28, 1909, as a relief pitcher. He pitched three innings, allowing four runs on four hits, four walks, and three hit by pitches. After the game, the Highlanders demoted Ford to the Jersey City Skeeters of the Eastern League, where he spent the rest of the 1909 season.[2] With Jersey City, he began to use the emery ball during games by hiding a piece of emery paper in his baseball glove. He pretended to be throwing a spitball, which was still legal at the time.[13]

Ford pitched for the Highlanders in 1910, and tried to disguise his emery ball as a "slide ball", a type of spitball that could move side-to-side, in addition to up and down.[16] Ford won 26 games against six losses for the Highlanders,[3] and threw complete games in all 26 wins.[17] He also had a 1.65 earned run average (ERA), which was the seventh-best in the American League, and 209 strikeouts, which was the fourth-most.[2][18] Ford also shared the secret of his emery ball with teammates Eddie Foster and Earle Gardner, who he roomed with when the Highlanders were traveling.[12]

For the 1911 season, the Highlanders paid Ford a $5,500 salary ($179,850 in current dollar terms), second-highest on the team behind only Hal Chase, the first baseman and manager.[19] In 1911, Ford won 22 games and lost 11.[17] He also had a 2.27 ERA, which was the seventh-best in the American League, and 158 strikeouts, which was the fifth-most.[2][20] In 1912, he only won 13 games while losing 21, and his strikeout total decreased to 112.[1][21] His 21 losses, 115 earned runs, and 11 home runs allowed were the most in the American League.[22] Ford had 13 wins, 18 losses, and a 2.66 ERA in the 1913 season, with only 72 strikeouts.[23] During the 1913 season, Ford announced that he was giving up the spitball because of the strain that it put on his shoulder and wrist.[24]

New York attempted to cut Ford's salary before the 1914 season,[2] so he jumped to the Buffalo Buffeds of the outlaw Federal League.[25] He had a 21–6 win–loss record for Buffalo in 1914 with 123 strikeouts; his .778 winning percentage was the best in the Federal League that year, and his 1.82 ERA was the second-best, behind Claude Hendrix.[17][26][27] He was reported to be using a knuckleball during the 1914 season.[28]

Later career

In September 1914, Ray Keating, who had learned the emery ball from Sweeney, was caught using it.[29] The major leagues decided to ban the pitch, with Ban Johnson, president of the American League, calling for a $100 fine ($3,042 in current dollar terms) and a 30-day suspension for anyone caught attempting it.[30] The other major leagues followed suit.[31][32]

Unable to use the emery ball, Ford struggled as he attempted to develop a new pitch, and was released from Buffalo during July.[33] He was re-signed later in the month.[34] Ford won five games and lost nine,[17] with a 4.52 ERA, for the 1915 season.[35]

Following the collapse of the Federal League, his contractual rights reverted to the Yankees, who gave him his unconditional release.[36] Returning to the minor leagues, Ford pitched for the Denver Bears of the Western League in 1916 and 1917. In July 1917, Denver sold Ford to the Toledo Iron Men of the American Association.[37] In 1918, he was playing in a semi-professional league.[38]

In 1922, Ford and Bee Lawler served as the coaches for the Minnesota Golden Gophers baseball team, the college baseball team representing the University of Minnesota.[39]

Personal life and honors

Ford married Mary Hunter Bethell in 1912. They had two daughters.[2]

After his retirement from baseball, Ford graduated from college.[40] His family moved to Rockingham, North Carolina, near Mary's hometown, of Reidsville,[17] in 1923. He went into banking and worked as a cashier in a local bank. In the 1930s, he worked for an engineering firm in New York City as a draftsman.[40][41]

Mary died in 1957. When she did, Ford moved back to Rockingham, and lived a quiet life in retirement. Ford died of a heart attack on January 24, 1960, in Rockingham.[2][41]

Ford was posthumously elected to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1987,[42] into the Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame and Museum in 2002,[43] and into the Manitoba Baseball Hall of Fame in 2004.[44]

See also

- List of Major League Baseball annual saves leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career ERA leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career WHIP leaders

References

- ^ a b "Russ Ford 30 Tomorrow". Saskatoon Daily Star. April 24, 1913. p. 12. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Morgan, T. Kent; Jones, David. "Russ Ford". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Mackie, John (March 6, 1999). "Baseball cards immortalize some early pros". The Vancouver Sun. p. 25. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Amateur Ball Fans: Local Enthusiasts Waiting For First Of April". Star Tribune. March 13, 1904. p. 30. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "15 Jan 1911". The Star Press. January 15, 1911. p. 10. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Gallery of Base Ball Players". The Gazette. April 3, 1906. p. 8. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Millers Make It Four Out Of Five". Star Tribune. July 22, 1904. p. 9. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Many Releases Given". Star Tribune. April 17, 1905. p. 7. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Manager Hill Gives Out Team". The Gazette. February 23, 1906. p. 5. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Russ Ford And Ronan Have Both Been Drafted". The Gazette. October 25, 1906. p. 6. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dickson, Paul (1989). The Dickson Baseball Dictionary. United States: Facts on File. p. 147. ISBN 0816017417.

- ^ a b "Sweeney Tells About The Emery Ball Discovery". Intelligencer Journal. May 19, 1916. p. 8. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b ""Emery Ball" His Secret". The Kansas City Times. January 6, 1916. p. 10. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Russ Ford Badly Wanted". Chattanooga Daily Times. August 2, 1908. p. 10. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Russ Ford to New York". The Gazette. August 28, 1908. p. 8. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Russ Ford Invents a New Curve Known as the Slide Ball". Detroit Free Press. May 8, 1910. p. 22. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e "Ford Posted 26-6 Record As Rookie". The Charlotte Observer. June 14, 1959. p. 4-F. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1910 American League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "Salary Slashes Were Justifiable". The Morning News. February 5, 1917. p. 11. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1911 American League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "1912 New York Highlanders Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "1912 American League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "1913 New York Yankees Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "Russ Ford Abandons Famous "Spit" Ball". Star Tribune. June 29, 1913. p. 18. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Buffalo Feds Get "Russ" Ford, King of Moist-Ball Pitchers". The Buffalo Courier. August 18, 2018. p. 10. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1914 Buffalo Buffeds Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "1914 Federal League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "Russ Ford As Good As Ever". The Winnipeg Tribune. July 21, 1914. p. 10. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Russell Ford Quits". Beaver County Republican. July 20, 1917. p. 3. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Emery Ball To Be Recorded As One Of The Year's Discoveries". The Miami News. October 8, 1914. p. 8. Retrieved April 28, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Sport Snapshots". The Times-Tribune. March 4, 1915. p. 15. Retrieved April 28, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cronin, R.A. (March 8, 1915). "In the Looking Glass". The Oregon Daily Journal. p. 8. Retrieved April 28, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Russ Ford Quits The Buf-Feds". The Buffalo Enquirer. July 14, 1915. p. 8. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Russ Ford Returns To Buf-Feds". The Buffalo Enquirer. July 24, 1915. p. 6. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1915 Buffalo Blues Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "Russ Ford is Let Go by Yankees". The Winnipeg Tribune. April 26, 1916. p. 12. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Russ Ford to Toledo". Evening Star. July 27, 1917. p. 13. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Russ Ford Hurling For Shipbuilders". The Atlanta Constitution. July 15, 1918. p. 6. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Sportfolio". The Minneapolis Star. November 23, 1922. p. 6. Retrieved April 25, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Barton, George A. (June 14, 1940). "Sportographs". Star Tribune. p. 22. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Russ Ford, Ex-Yankee Star, Dead". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. United Press International. January 25, 1960. p. 31. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jenkins named to Canada's baseball Hall". The Ottawa Citizen. Canadian Press. February 3, 1987. p. 52. Retrieved April 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Honoured Members Database". Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "Russel Ford". Manitoba Baseball Hall of Fame. April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball Reference

- Russ Ford at Find a Grave