Contents

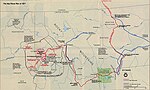

The Attack on Looking Glass Camp was a military attack carried out on July 1, 1877 as part of the Nez Perce War by Captain Stephen G. Whipple of the United States Army on the village of the Native American chief Looking Glass, located near the Clearwater River, near the present-day town of Kooskia. Glass had refused to join the other Nez Perce factions hostile to the Americans, so General Oliver Otis Howard, relying on reports that Glass posed a threat, gave the order to arrest him and his group.

When the Americans arrived, Looking Glass told them they were living in peace and asked them to leave, but a shot fired by one of the civilian volunteers accompanying the soldiers precipitated the confrontation. Surprised by the attack, the Amerindians fled their village and took refuge in the surrounding hills. The soldiers then ransacked the camp, capturing nearly 700 horses and taking them back to Mount Idaho.

Although Looking Glass's camp was destroyed, the mission was a failure for the Americans, since Whipple was unable to capture the group of Native Americans. Moreover, Looking Glass, furious at the way he had been treated by the Americans, chose to join the other groups of hostile Nez-Percés, complicating the American army's task.

Context

In 1855, the Nez Perce signed a treaty with the United States that established the boundaries of a reservation encompassing much of their traditional lands.[1] In 1863, however, following the discovery of gold within the reservation, the U.S. government imposed a new treaty on the Nez Perce, reducing the size of the reservation by almost 90%.[2] Several groups, including Looking Glass, refused to sign the "Treaty of Flight" and continued to live outside the reservation until the spring of 1877. In May 1877, after several incidents between settlers and the Nez-Percés, General Oliver Otis Howard, head of the Columbia Department, gave the rebels 30 days to return to the reservation.[3] On June 14, 1877, as the various groups of Nez Perces gathered near Tolo Lake before finally rejoining the reservation, several young Nez Perces belonging to White Bird's group set out along the Salmon River to avenge the death of a relative killed by whites a few years earlier. Back at camp, they announced that they had killed four men and wounded another.[4] Over the next two days, some sixteen Nez Perces, carried away by the fury of war, launched new raids on the surrounding villages, killing 18 whites and severely wounding 6 others.[5]

Knowing that the army would respond to these attacks, most of the Amerindians prepared to leave. The Looking Glass group returned to their lands within the boundaries of the reservation, near the Clearwater, hoping to avoid any confrontation with the soldiers.[4] The groups of Chief Joseph, Toohoolhoolzote and White Bird gathered not far from the mouth of Cottonwood Creek,[6] then planned to settle near Looking Glass's camp. Furious with White Bird for not having been able to prevent the young men of his group from committing these attacks, Looking Glass opposed their coming and addressed these words to them:[7]

My hands are clean of white men's blood, and I want you to know they will so remain. You have acted like fools in murdering white men. I will have no part in these things, and have nothing to do with such men. If you are determined to go and fight, go and fight yourselves and do not attempt to embroil me or my people. Go back with your warriors; I do not want any of your band in my camp. I wish to live in peace.

Chief Joseph, Toohoolhoolzote and White Bird then set off for White Bird Canyon, some forty kilometers to the south.

When General Howard received news of these incidents on June 15 at Fort Lapwai, he sent two companies of cavalry under the command of Captain David Perry to assist the inhabitants of Grangeville and Mount Idaho, some 80 km from Lapwai.[8] While there, Perry was persuaded by the people of Grangeville to pursue the Indians before they crossed the Salmon River. At dawn on June 17, American troops entered White Bird Canyon, while the Nez Perce stood ready to confront them. The ensuing battle was a heavy defeat for the American army; Perry lost 34 of his men, while the Nez Perce suffered no casualties.

Having learned of the scale of the defeat, General Howard mobilized troops and took charge of the campaign.[9] Certain that the Americans would be back in force, the Amerindians preferred to retreat to the other side of the Salmon River, even if it meant re-crossing at another point if the soldiers decided to pursue them. On June 29, just as Howard was about to cross, he received word that Looking Glass and his party posed a threat and might join the conflict.[10] Volunteers from Mount Idaho reported that Nez Perces from Looking Glass's group had looted two properties near the Clearwater and set fire to one of them,[11][note 1] and reports suggested that at least twenty of them had joined the hostile Native Americans, when in fact only a few had actually participated in the battle of White Bird Canyon.[12] Other rumors claimed that Looking Glass and his warriors were preparing to attack the surrounding villages.[13] Until then, Howard had always been skeptical that Looking Glass could play a role in the conflict, and was satisfied that he had chosen to stay on his land,[14] but this latest information changed his mind and he ordered Captain Stephen Girard Whipple to "arrest Indian Chief Looking Glass, and all other Indians who may be encamped with or near him, between the arms of the Clearwater, and imprison them at Mount Idaho, turning them over to the volunteer organization of that place for safe keeping".[11]

Forces involved

United States Army

The soldiers sent by General Howard formed Companies E and L of the 1st Cavalry Regiment, totaling 67 men,[11] plus twenty civilian volunteers in Mount Idaho were led by Darius B. Randall.[15] Company L was commanded by Captain Stephen G. Whipple, with Edwin H. Shelton as first lieutenant and Sevier M. Rains as second lieutenant.[15] Company E was led by Captain William H. Winters, with Albert G. Forse as first lieutenant and William H. Miller as second lieutenant.[15] The troops initially carried two Gatling guns, but these were left at Mount Idaho before reaching the Native American camp.

Nez Perces

The Looking Glass camp was situated on the banks of Clear Creek, not far from its confluence with the Central Branch of the Clearwater, near the present-day town of Kooskia and some thirty kilometers northeast of Mount Idaho.[15] It was home to a dozen tipis and, on the day of the attack, probably fewer than twenty warriors, as well as around 120 women, children and elderly people.[16] Most of the inhabitants were followers of the Waashat Religion, and as July 1 was a Sunday, some of them went to Kamiah to take part in a religious ceremony.[16]

The Amerindians called this place Kamnaka, where they grew potatoes, corn, squash and melons, and some of them raised dairy cows.[15][17]

Prelude

The two American cavalry companies left the Salmon River at 9 p.m. on June 29, heading for Mount Idaho, which they reached at dawn on June 30.[11] There, Whipple left his two Gatling guns and a few men to maneuver them, and after giving the rest of the troops several hours to rest, he set off again in the late afternoon, accompanied by twenty civilian volunteers led by Darius B. Randall.[18] Whipple planned to ride at night, hoping to arrive at the Native camp before dawn to take its occupants by surprise,[note 2] but due to the rugged nature of the terrain and a miscalculation (the camp was fifteen kilometers further away than planned), they didn't arrive until 7 a.m. on the morning of July 1, well after sunrise.[15] The American troops dismounted and positioned themselves on the crest of a hill, some 400 m west of the Amerindian village from which they were separated by Clear Creek.[16]

Alerted by the arrival of the soldiers, Looking Glass, who was having breakfast in his tepee with several of his men, sent Peopeo Tholekt to tell them that they were living here in peace, and asked them to leave them alone.[20] The young warrior mounted his horse, crossed Clear Creek and climbed the hill where the Americans were stationed.[16] One of the volunteers welcomed him in nez perce, and Peopeo Tholekt delivered Looking Glass' message.[21] As he talked to the interpreter, other – apparently drunk – volunteers approached and one of them asked him in English: "You Looking Glass?", poking him in the ribs with the barrel of his rifle.[21] After the interpreter had convinced him that it wasn't Looking Glass, he asked Peopeo Tholekt to inform his boss so that he could come and negotiate in person.[22]

Having seen how the Americans had treated Peopeo Tholekt, and fearing that they might kill their leader, the Nez Perces advised Looking Glass not to go.[22] He asked Peopeo Tholekt, and Kalowet who spoke a little English, to return to the American troops and ask them once again to leave.[23] After planting a flagpole between the Looking Glass tepee and Clear Creek, on which a white flag was hung as a white flag, the two Amerindians went back to the Americans and repeated their message of peace.[23] Again, the same volunteer threatened to kill Peopeo Tholekt, certain that he was Looking Glass, but the interpreter pointed out that he was too young to be Looking Glass and made him lower his weapon.[24] This time, one of the officers,[note 3] accompanied by two or three men and the interpreter, returned to the camp with Peopeo Tholekt and Kalowet and asked to see Looking Glass.[22] As they arrived at the white flag, someone – probably one of the volunteers – fired a shot in the direction of the camp and wounded an Amerindian in the hip, putting an end to all attempts at negotiation.[22]

Attack

After the first shot, the Americans accompanying the Amerindians to the camp turned their horses around and hurried back to the rest of the troops.[22] A general fusillade broke out in the camp, causing panic among its occupants.[19] Despite the late hour, the attack took the Amerindians by surprise, and very few attempted to fight back.[25] In small groups, they fled to the north and east of the village, seeking cover from the soldiers in the bushes.[25] Soon, however, the firing ceased and the American soldiers came down the hill in tirailleur formation, across Clear Creek and into the deserted camp.[25] The Nez-Percés had taken refuge upstream from Clearwater and on a hill to the east of the village, out of range of American fire.[25]

At the same time, Lieutenants Forse and Shelton, accompanied by some 20 men, captured the Nez Percés' herd of horses.[26] The Americans then ransacked the Amerindians' camp, searching their tipis for the few valuables and destroying the rest of their possessions. The soldiers then attempted to set fire to the tipis, but only two actually caught fire.[26] The Americans finally returned to Mount Idaho, taking with them more than 600 horses belonging to the Nez-Percés.[note 4]

Results and consequences

We thus stirred up a new hornet's nest.

Général Oliver Otis Howard Brown (1967), p. 168

The attack was a major blow to the Nez-Percés of Looking Glass. Their homes and most of their possessions were destroyed, as were their vegetable gardens, which were ransacked and trampled by the Americans' horses.[27] They also lost most of their horses and cattle.[27] According to Peopeo Tholekt, three or four Nez-Percés were wounded, one fatally.[22] A woman and her baby were also killed while attempting to cross the Clearwater north of the village, when their horse was swept away by the current.[22] The Americans suffered no casualties.[26]

In a report, Whipple states that "an opportunity was given Looking Glass to surrender, which he at first promised to accept, but afterward defiantly refused, and the result was that severals Indians were killed"[16] but Peopeo Tholekt insists that at no time did Looking Glass agree to surrender and that he instead sought to avoid meeting the soldiers.[28]

Despite Whipple's apparent success, General Howard was not entirely satisfied with the outcome.[29] Due to the late arrival at the camp and the loss of the element of surprise, the main objective of capturing Looking Glass and his group was not achieved.[29] Worse still, the American army's task was complicated by the fact that Looking Glass, furious at having been treated in this way, chose to join the other Nez-Percés factions hostile to the Americans,[29] as did the Palouse chief Husishusis Kute and his group based not far from Looking Glass's camp.[22] This not only strengthened the ranks of the Nez-Percés fighters, but also gave them, in Looking Glass, a recognized and respected military leader who was familiar with the Montana lands to which the Amerindians would later head.[30]

Places of remembrance

Since 1966, the site of the Looking Glass camp has been occupied by a fish hatchery run by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. On July 1, 2000, a wildlife observation trail was inaugurated around the site, and in 2003, a replica of an ancient bronze historical marker originally erected in 1928 was installed to commemorate the July 1, 1877 attack.[31] A historical sign has also been installed along U.S. Route 12.

Notes

- ^ Brown (1967), pp. 164–166 asserts that the looting was committed by whites, and suggests that the reports were formulated to enable volunteers to attack the Looking Glass group.

- ^ This was a tactic regularly used by the American army against Native Americans at the time, particularly when small encampments were involved Greene (2000), p. 52.

- ^ Later identified as Lieutenant Sevier M. Rains (Brown (1967), p. 168).

- ^ What happened to the horses is uncertain. Brown 1967, p. 168 suggests that they escaped shortly afterwards.

References

- ^ Greene (2000), p. 8

- ^ West (2009), pp. 85–94

- ^ Greene (2000), pp. 12–24

- ^ a b Greene (2000), p. 30

- ^ West (2009), p. 126-130

- ^ McDermott (2003), p. 12

- ^ Cozzens, Peter (2001). Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars, 1865-1890: the wars for the Pacific Northwest. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books. p. 467. ISBN 978-0-8117-0573-8. OCLC 45248304..

- ^ West (2009), p. 131

- ^ Greene (2000), p. 44

- ^ McDermott (2003), p. 124

- ^ a b c d Greene (2000), p. 51

- ^ Howard (1978), p. 184

- ^ Howard (1978), pp. 184–185

- ^ Greene (2000), pp. 50–51

- ^ a b c d e f Greene (2000), p. 52

- ^ a b c d e Greene (2000), p. 54

- ^ Mcwhorter (2001), p. 272

- ^ Greene (2000), pp. 51–52

- ^ a b Greene (2000), p. 55

- ^ Brown (1967), pp. 167–168

- ^ a b Mcwhorter (2001), p. 265

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brown (1967), p. 168

- ^ a b Mcwhorter (2001), p. 266

- ^ Mcwhorter (2001), p. 267

- ^ a b c d Greene (2000), p. 56

- ^ a b c Greene (2000), p. 57

- ^ a b Mcwhorter (2001), p. 270

- ^ Mcwhorter (2001), p. 170-171

- ^ a b c Greene (2000), p. 58

- ^ West (2009), p. 143

- ^ "Looking Glass Village Site" (PDF). fws.gov. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

Bibliography

- Brown, Mark Herbert (1967). The flight of the Nez Perce. New York: Putnam. ISBN 0803260695. OCLC 633657.

- Forczyk, Robert (2011). Nez Perce 1877: the last fight. Oxford: Osprey Publishin. ISBN 978-1-84908-192-4. OCLC 709777768.

- Greene, Jerome A. (2000). Nez Perce summer, 1877: the U.S. Army and the Nee-Me-Poo crisis. Helena: Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-917298-68-4. OCLC 43951833.

- Howard, Helen Addison (1978). Saga of Chief Joseph. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7202-6.

- Josephy, Alvin M. (1997). The Nez Perce Indians and the opening of the Northwest. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-85011-4. OCLC 36170547.

- McDermott, John D. (2003) [1978]. Forlorn Hope: The Nez Perce victory at White Bird Canyon. Cadwell: Caxton Press. ISBN 0-87004-435-4. OCLC 758476617.

- Mcwhorter, Lucullus Virgil (2001) [1952]. Hear Me, My Chiefs!: Nez Perce History and Legend. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers. ISBN 978-0-87004-310-9. OCLC 71826048.

- West, Elliott (2009). The last Indian war: the Nez Perce story. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513675-3. OCLC 255902883.

- Wolf, Yellow; Mcwhorter, Lucullus Virgil (1940). Yellow Wolf: his own story. Caldwell: The Caxton Printers, Ltd. OCLC 29580343.

External links

- "Looking Glass' 1877 Camp History". nps.gov.