Contents

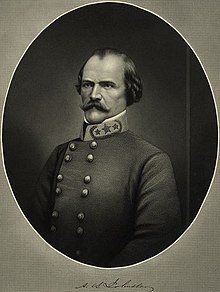

Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) was an American military officer who served as a general in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army. He saw extensive combat during his 34-year military career, fighting actions in the Black Hawk War, the Texas-Indian Wars, the Mexican–American War, the Utah War, and the American Civil War.

Considered by Confederate States President Jefferson Davis to be the finest general officer in the Confederacy before the later emergence of Robert E. Lee, he was killed early in the Civil War at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6, 1862. Johnston was the highest-ranking officer on either side killed during the entire war. Davis believed the loss of General Johnston "was the turning point of our fate."

Johnston was unrelated to Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston.

Early life and education

Johnston was born in Washington, Kentucky, the youngest son of Dr. John and Abigail (Harris) Johnston. His father was a native of Salisbury, Connecticut. Although Albert Johnston was born in Kentucky, he lived much of his life in Texas, which he considered his home.[1] He was first educated at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, where he met fellow student Jefferson Davis. Both were appointed to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, Davis two years behind Johnston.[2] In 1826,[3] Johnston graduated eighth of 41 cadets in his class from West Point with a commission as a brevet second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Infantry.[4]

Johnston was assigned to posts in New York and Missouri. In August 1827 he participated in the expedition to capture Red Bird, the rebellious Winnebago chief. Johnston later wrote: "I must confess that I consider Red Bird one of the noblest and most dignified men I ever saw... He said: 'I have offended. I sacrifice myself to save my country.'"[5] Johnston served in the brief Black Hawk War of 1832 as chief of staff to Brevet Brigadier General Henry Atkinson. The commander praised Johnston for "talents of the first order, a gallant soldier by profession and education and a gentleman of high standing and integrity."[6]

Marriage and family

In 1829, he married Henrietta Preston, sister of Kentucky politician and future Civil War general William Preston. They had three children, of whom two survived to adulthood. Their son, William Preston Johnston, became a colonel in the Confederate States Army.[7] The senior Johnston resigned his commission in 1834 to care for his dying wife in Kentucky, who succumbed two years later to tuberculosis.[2]

After serving as Secretary of War for the Republic of Texas in 1838–40, Johnston resigned and went back to Kentucky.[3] In 1843, he married Eliza Griffin, his late wife's first cousin. The couple moved to Texas, where they settled on a large plantation in Brazoria County. Johnston named the property "China Grove". Here they raised Johnston's two children from his first marriage and the first three children born to Eliza and him. A sixth child was born later when the family lived in Los Angeles, where they had permanently settled.

Texian Army

Johnston moved to Texas in 1836 and[3] enlisted as a private in the Texian Army[3] after the Texas War of Independence from the Republic of Mexico. He was named Adjutant General as a colonel in the Republic of Texas Army on August 5, 1836. On January 31, 1837, he became senior brigadier general in command of the Texas Army.

On February 5, 1837, Johnston fought in a duel with Texas Brigadier General Felix Huston, who was angered and offended by Johnston's promotion. Huston had been the acting commander of the army and perceived Johnston's appointment as a slight from the Texas government. Johnston was shot through the hip and severely wounded, requiring him to relinquish his post during his recovery.[8]

Afterwards, Johnston said he fought Huston "as a public duty... he had but little respect for the practice of dueling." He believed that the "safety of the republic depended upon the efficiency of the army... and upon the good discipline and subordination of the troops, which could only be secured by their obedience to their legal commander. General Huston embodied the lawless spirit in the army, which had to be met and controlled at whatever personal peril."[9]

Many years later, Huston said that the duel was "a shameful piece of business, and I wouldn't do it again under any circumstances... Why, when I reflect upon the circumstances, I hate myself... that one act blackened all the good ones of my life. But I couldn't challenge Congress; and President Houston, although a duelist, was too far above me in rank. Well, thank God, I didn't kill him."[10]

On December 22, 1838, Mirabeau B. Lamar, the second president of the Republic of Texas, appointed Johnston as Secretary of War. He defended the Texas border against Mexican attempts to recover the state in rebellion. In 1839, he campaigned against Native Americans in northern Texas during the Cherokee War of 1838–39. At the Battle of the Neches, Johnston and Vice President David G. Burnet were both cited in the commander's report "for active exertions on the field" and "having behaved in such a manner as reflects great credit upon themselves."[11] In February 1840, he resigned and returned to Kentucky.

United States Army

When the United States declared war on Mexico in May 1846, Johnston rode 400 miles from his home in Galveston to Port Isabel to volunteer for service in Brigadier General Zachary Taylor's Army of Occupation. Johnston was elected as colonel of the 1st Texas Rifle Volunteers but the enlistments of his soldiers ran out just before the army's advance on Monterrey, so Taylor appointed him as the inspector general of Brigadier General William O. Butler's division of volunteers. Johnston convinced a few volunteers of his former regiment to stay on and fight.

During the Battle of Monterrey, Butler was wounded and carried to the rear, and Johnston assumed an active leadership role in the division. Future U.S. general, Joseph Hooker, was with Johnston at Monterrey and wrote: "It was through [Johnston's] agency, mainly, that our division was saved from a cruel slaughter... The coolness and magnificent presence [that he] displayed on this field... left an impression on my mind that I have never forgotten."[6] General Taylor considered Johnston "the best soldier he had ever commanded."[12]

Johnston resigned from the army just after the battle of Monterrey in October 1846. He had promised his wife, Eliza, that he would only volunteer for six months' service. In addition, President James K. Polk's administration's preference for officers associated with the Democratic Party prevented the promotion of those, such as Johnston, who were perceived as Whigs:

Authorized to appoint a large number of officers in the increased military force, raised directly by the United States, an unjust discrimination was made in favor of Democrats... Not one Whig was included, and not one of the Democratic appointees had seen service in the field, or possessed the slightest pretension to military education. Such able graduates of West Point as Henry Clay, jun., and William R. McKee, were compelled to seek service through State appointments in volunteer regiments, while Albert Sidney Johnston, subsequently proved to be one of the ablest commanders ever sent from the Military Academy, could not obtain a commission from the General Government. In the war between Mexico and Texas, by which the latter had secured its independence, Johnston had held high command, and was perhaps the best equipped soldier, both by education and service, to be found in the entire country outside the regular army at the time of the Mexican war. General Taylor urged the President to give Johnston command of one of the ten new regiments. Johnston took no part in politics; but his eminent brother, Josiah Stoddard Johnston, long a senator from Louisiana, was Mr. Clay's most intimate friend in public life, and General Taylor's letter was not even answered.[13]

He remained on his plantation after the war until he was appointed by later 12th president Zachary Taylor to the U.S. Army as a major and was made a paymaster in December 1849 for a district of Texas encompassing the military posts from the upper Colorado River to the upper Trinity River.[3] He served in that role for more than five years, making six tours and traveling more than 4,000 miles (6,400 km) annually on the Indian frontier of Texas. He served on the Texas frontier at Fort Mason and elsewhere in the western United States.

In 1855, 14th president Franklin Pierce appointed him colonel of the new 2nd U.S. Cavalry (the unit that preceded the modern 5th U.S.), a new regiment, which he organized, his lieutenant colonel being Robert E. Lee, and his majors William J. Hardee and George H. Thomas.[3] Other subordinates in this unit included Earl Van Dorn, Edmund Kirby Smith, Nathan G. Evans, Innis N. Palmer, George Stoneman, R.W. Johnson, John B. Hood, and Charles W. Field, all future Civil War generals.[14] On March 31, 1856, Johnston received a promotion to temporary command of the entire Department of Texas. He campaigned aggressively against the Comanche, writing to his daughter that "the Indians harass our frontiers and the 2nd Cavalry and other troops thrash them wherever they catch them."[15] In March 1857, Brigadier General David E. Twiggs was appointed permanent commander of the department and Johnston returned to his position as colonel of the 2nd Cavalry.

Utah War

As a key figure in the Utah War, Johnston took command of the U.S. forces dispatched to crush the Mormon rebellion in November 1857. Their objective was to install Alfred Cumming as governor of the Utah Territory, replacing Brigham Young, and restore U.S. legal authority in the region. As Johnston had replaced Brigadier General William S. Harney in command, he only joined the army after it had already departed for Utah. Johnston's adjutant general, and future U.S. general in the Civil War, Major Fitz John Porter wrote: "Experienced on the Plains and of established reputation for energy, courage, and resources, [Johnston's] presence restored confidence at all points, and encouraged the weak-hearted and panic-stricken multitude. The long chain of wagons, kinked, tangled, and hard to move, uncoiled and went forward smoothly."[16]

Johnston worked tirelessly over the next few months to maintain the effectiveness of his army in the harsh winter environment at Fort Bridger, Wyoming. Major Porter wrote to an associate: "Col. Johnston has done everything to add to the efficiency of the command – and put it in a condition to sustain the dignity and honor of the country – More he cannot do… Don't let any one come here over Col. Johnston – It would be much against the wishes and hopes of everyone here – who would gladly see him a Brigadier General."[17] Even the Mormons commended Johnston's actions, with the Salt Lake City Deseret News reporting that "It takes a cool brain and good judgment to maintain a contented army and healthy camp through a stormy winter in the Wasatch Mountains."[18]

Johnston and his troops hoped for war. They had learned of the Mountain Meadows Massacre and wanted revenge against the Mormons. However, a peaceful resolution was reached after the army had endured the harsh winter at Fort Bridger. In late June 1858, Johnston led the army through Salt Lake City without incident to establish Camp Floyd some 50 miles distant. In a report to the War Department, Johnston reported that "horrible crimes… have been perpetrated in this territory, crimes of a magnitude and of an apparently studied refinement in atrocity, hardly to be conceived of, and which have gone unwhipped of justice."[19] Nevertheless, Johnston's army peacefully occupied the Utah Territory. U.S. Army Commander-in-Chief, Major General Winfield Scott, was delighted with Johnston's performance during the campaign and recommended his promotion to brevet brigadier general: "Colonel Johns[t]on is more than a good officer – he is a God send to the country thro' the army."[20] The Senate confirmed Johnston's promotion on March 24, 1858.

With regard to the relations established by Johnston with the Native American tribes of the area, Major Porter reported that "Colonel Johnston took every occasion to bring the Indians within knowledge and influence of the army, and induced numerous chiefs to come to his camp... Colonel Johnston was ever kind, but firm, and dignified to them... The Utes, Pi-Utes, Bannocks, and other tribes, visited Colonel Johnston, and all went away expressing themselves pleased, assuring him that so long as he remained they would prove his friends, which the colonel told them would be best for them. Thus he effectively destroyed all influence of the Mormons over them, and insured friendly treatment to travelers to and from California and Oregon."[21]

In August 1859, parts of Johnston's Army of Utah were implicated as participants in an alleged massacre at Spring Valley, a retaliation against an Indian massacre of an emigrant train to California. There are conflicting reports of the event and Johnston only referenced it in a November 1859 report to Scott. He wrote: "I have ascertained that three [emigrant] parties were robbed, and ten or twelve of their members, comprising men, women, and children, murdered... The perpetrators of the robbery of the first party were severely chastised by a detachment of dragoons, under the command of Lieutenant Gay. The troops failed to discover the robbers of the last two parties that were attacked. They are supposed to be vagabonds from the Shoshonee (sic) or Snake and Bannack (sic) Indians, whose chiefs deny any complicity with these predatory bands. There is abundant evidence to prove that these robber bands are accompanied by white men, and probably instigated and led by them. On that account I am inclined to believe the disclaimer of the Indians referred to, of having any knowledge of the robberies or any share in the plunder." The only evidence of the massacre is the account of Elijah Nicholas Wilson (written in 1910, about 51 years after the incident) and oral histories.[22][23]

In late February 1860, Johnston received orders from the War Department recalling him to Washington D.C. to prepare for a new assignment. He spent 1860 in Kentucky until December 21, when he sailed for California to take command of the Department of the Pacific.

Slavery

Johnston was a slave owner and a strong supporter of slavery. By 1846, he owned four slaves in Texas.[24] In 1855, having discovered that a slave was stealing from the Army payroll, Johnston refused to have him physically punished and instead sold him for $1,000 to recoup the losses. Johnston explained that "whipping will not restore what is lost and it will not benefit the [culprit], whom a lifetime of kind treatment has failed to make honest."[25] In 1856, he called abolitionism "fanatical, idolatrous, negro worshipping" in a letter to his son, fearing that the abolitionists would incite a slave revolt in the Southern states.[26] Upon moving to California, Johnston sold one slave to his son and freed another, Randolph or "Ran", who agreed to accompany the family on the condition of a $12/month contract for five more years of servitude. Ran accompanied Johnston throughout the American Civil War until the latter's death. Johnston's wife Eliza celebrated the absence of blacks in California, writing, "where the darky is in any numbers it should be as slaves."[27]

American Civil War

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Johnston was the commander of the U.S. Army Department of the Pacific[3] in California. Like many regular army officers from the Southern United States, he opposed secession. Nevertheless, Johnston resigned his commission soon after he heard of the Confederate states' declarations of secession. The War Department accepted it on May 6, 1861, effective May 3.[28] On April 28, he moved to Los Angeles, the home of his wife's brother John Griffin. Considering staying in California with his wife and five children, Johnston remained there until May. A sixth child was born in the family home in Los Angeles. His eldest son, Capt. Albert S. Johnston, Jr. was later killed in an accidental explosion on a steamer ship while on liberty in Los Angeles in 1863.[29]

Soon, Johnston enlisted in the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles (a pro-Southern militia unit) as a private, leaving Warner's Ranch on May 27.[30] He participated in their trek across the Southwestern deserts to Texas, crossing the Colorado River into the Confederate Territory of Arizona on July 4, 1861. His escort was commanded by Alonzo Ridley, Undersheriff of Los Angeles, who remained at Johnston's side until he was killed.[31]

Early in the Civil War, Confederate President Jefferson Davis decided that the Confederacy would attempt to hold as much territory as possible, distributing military forces around its borders and coasts.[32] In the summer of 1861, Davis appointed several generals to defend Confederate lines from the Mississippi River east to the Allegheny Mountains.[33] Aged 58 when the war began, Johnston was old by Army standards. He came east to offer his service for the Confederacy without having been promised anything, merely hoping for an assignment.

The most sensitive, and in many ways, the most crucial areas, along the Mississippi River and in western Tennessee along the Tennessee and the Cumberland rivers[34] were placed under the command of Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk and Brig. Gen. Gideon J. Pillow. The latter had initially been in command in Tennessee as that State's top general.[35] Their impolitic occupation of Columbus, Kentucky, on September 3, 1861, two days before Johnston arrived in the Confederacy's capital of Richmond, Virginia, after his cross-country journey, drove Kentucky from its stated neutrality.[36][37] The majority of Kentuckians allied with the U.S. camp.[38] Polk and Pillow's action gave U.S. Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant an excuse to take control of the strategically located town of Paducah, Kentucky, without raising the ire of most Kentuckians and the pro-U.S. majority in the State legislature.[39][40]

Confederate command in Western Theater

On September 10, 1861, Johnston was assigned to command the huge area of the Confederacy west of the Allegheny Mountains, except for coastal areas. He became commander of the Confederacy's western armies in the area often called the Western Department or Western Military Department.[41][42] Johnston's appointment as a full general by his friend and admirer Jefferson Davis had already been confirmed by the Confederate Senate on August 31, 1861. The appointment had been backdated to rank from May 30, 1861, making him the second-highest-ranking general in the Confederate States Army. Only Adjutant General and Inspector General Samuel Cooper ranked ahead of him.[43] After his appointment, Johnston immediately headed for his new territory.[44] He was permitted to call on Arkansas, Tennessee, and Mississippi governors for new troops. However, politics largely stifled this authority, especially concerning Mississippi.[41] On September 13, 1861, Johnston ordered Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer with 4,000 men to occupy Cumberland Gap in Kentucky to block U.S. troops from coming into eastern Tennessee. The Kentucky legislature had voted to side with the United States after the occupation of Columbus by Polk.[44] By September 18, Johnston had Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner with another 4,000 men blocking the railroad route to Tennessee at Bowling Green, Kentucky.[44][45]

Johnston had fewer than 40,000 men spread throughout Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Missouri.[46] Of these, 10,000 were in Missouri under Missouri State Guard Maj. Gen. Sterling Price.[46] Johnston did not quickly gain many recruits when he first requested them from the governors, but his more serious problem was lacking sufficient arms and ammunition for the troops he already had.[46] As the Confederate government concentrated efforts on the units in the East, they gave Johnston small numbers of reinforcements and minimal amounts of arms and material.[47] Johnston maintained his defense by conducting raids and other measures to make it appear he had larger forces than he did, a strategy that worked for several months.[47] Johnston's tactics had so annoyed and confused U.S. Brig. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman in Kentucky that he became paranoid and mentally unstable. Sherman overestimated Johnston's forces and was relieved by Brig. Gen. Don Carlos Buell on November 9, 1861. However, in his Memoirs, Sherman strongly rebutted this account.[48][49][50][51]

Battle of Mill Springs

East Tennessee (a heavily pro-U.S. region of the southern U.S. during the Civil War) was occupied for the Confederacy by two unimpressive brigadier generals appointed by Jefferson Davis: Felix Zollicoffer, a brave but untrained and inexperienced officer, and soon-to-be Maj. Gen. George B. Crittenden, a former U.S. Army officer with apparent alcohol problems.[52] While Crittenden was away in Richmond, Zollicoffer moved his forces to the north bank of the upper Cumberland River near Mill Springs (now Nancy, Kentucky), putting the river to his back and his forces into a trap.[53][54] Zollicoffer decided it was impossible to obey orders to return to the other side of the river because of the scarcity of transport and proximity of U.S. troops.[55] When U.S. Brig. Gen. George H. Thomas moved against the Confederates, Crittenden decided to attack one of the two parts of Thomas's command at Logan's Cross Roads near Mill Springs before the U.S. forces could unite.[55] At the Battle of Mill Springs on January 19, 1862, the ill-prepared Confederates, after a night march in the rain, attacked the U.S. soldiers with some initial success.[56] As the battle progressed, Zollicoffer was killed and the Confederates were turned back and routed by a U.S. bayonet charge, suffering 533 casualties from their force of 4,000 while Crittenden's conduct in the battle was so inept that subordinates accused him of being drunk.[57][58] The Confederate troops who escaped were assigned to other units as General Crittenden faced an investigation of his conduct.[59]

After the Confederate defeat at Mill Springs, Davis sent Johnston a brigade and a few other scattered reinforcements. He also assigned him Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard, who was supposed to attract recruits because of his victories early in the war and act as a competent subordinate for Johnston.[60] The brigade was led by Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd, considered incompetent. He took command at Fort Donelson as the senior general present just before U.S. Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant attacked the fort.[61] Historians believe the assignment of Beauregard to the west stimulated U.S. commanders to attack the forts before Beauregard could make a difference in the theater. U.S. Army officers heard that he was bringing 15 regiments with him, but this was an exaggeration of his forces.[62]

Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, Nashville

Based on the assumption that Kentucky neutrality would act as a shield against a direct invasion from the north, circumstances that no longer applied in September 1861, Tennessee initially had sent men to Virginia and concentrated defenses in the Mississippi Valley.[63][64] Even before Johnston arrived in Tennessee, construction of two forts had been started to defend the Tennessee and the Cumberland rivers, which provided avenues into the State from the north.[65] Both forts were located in Tennessee to respect Kentucky neutrality, but these were not in ideal locations.[65][66][67][68] Fort Henry on the Tennessee River was in an unfavorable low-lying location, commanded by hills on the Kentucky side of the river.[65] Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River, although in a better location, had a vulnerable land side and did not have enough heavy artillery to defend against gunboats.[65]

Maj. Gen. Polk ignored the problems of the forts when he took command. After Johnston took command, Polk at first refused to comply with Johnston's order to send an engineer, Lt. Joseph K. Dixon, to inspect the forts.[69] After Johnston asserted his authority, Polk had to allow Dixon to proceed. Dixon recommended that the forts be maintained and strengthened, although they were not in ideal locations, because much work had been done on them, and the Confederates might not have time to build new ones. Johnston accepted his recommendations.[69] Johnston wanted Major Alexander P. Stewart to command the forts, but President Davis appointed Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman as commander.[66][69]

To prevent Polk from dissipating his forces by allowing some men to join a partisan group, Johnston ordered him to send Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow and 5,000 men to Fort Donelson.[70] Pillow took up a position at nearby Clarksville, Tennessee, and did not move into the fort until February 7, 1862.[71][72] Alerted by a U.S. reconnaissance on January 14, 1862, Johnston ordered Tilghman to fortify the high ground opposite Fort Henry, which Polk had failed to do despite Johnston's orders.[73] Tilghman failed to act decisively on these orders, which were too late to be adequately carried out in any event.[73][74][75]

Gen. Beauregard arrived at Johnston's headquarters at Bowling Green on February 4, 1862, and was given overall command of Polk's force at the western end of Johnston's line at Columbus, Kentucky.[76][77] On February 6, 1862, U.S. gunboats quickly reduced the defenses of ill-sited Fort Henry, inflicting 21 casualties on the small remaining Confederate force.[78][79] Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman surrendered the 94 remaining officers and men of his approximately 3,000-man force, which had not been sent to Fort Donelson, before Grant's U.S. forces could even take up their positions.[78][80][81] Johnston knew he could be trapped at Bowling Green if Fort Donelson fell, so he moved his force to Nashville, the capital of Tennessee and an increasingly important Confederate industrial center, beginning on February 11, 1862.[82][83]

Johnston also reinforced Fort Donelson with 12,000 more men, including those under Floyd and Pillow, a curious decision given his thought that the U.S. gunboats alone could take the fort.[82] He ordered the fort commanders to evacuate the troops if the fort could not be held.[84] The senior generals sent to the fort to command the enlarged garrison, Gideon J. Pillow and John B. Floyd, squandered their chance to avoid having to surrender most of the garrison[85] and on February 16, 1862, Brig. Gen. Simon Buckner, having been abandoned by Floyd[86] and Pillow, surrendered Fort Donelson.[87] Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest escaped with his cavalry force of about 700 men before the surrender.[88][89][90] The Confederates suffered about 1,500 casualties, with an estimated 12,000 to 14,000 taken prisoner.[91][92] U.S. casualties were 500 killed, 2,108 wounded, and 224 missing.[92]

Johnston, who had little choice in allowing Floyd and Pillow to take charge at Fort Donelson based on seniority after he ordered them to add their forces to the garrison, took the blame and suffered calls for his removal because a full explanation to the press and public would have exposed the weakness of the Confederate position.[93] His passive defensive performance while positioning himself in a forward position at Bowling Green, spreading his forces too thinly, not concentrating his forces in the face of U.S. advances, and appointing or relying upon inadequate or incompetent subordinates subjected him to criticism at the time and by later historians.[94][95][96] The fall of the forts exposed Nashville to an imminent attack, and it fell without resistance to U.S. forces under Brig. Gen. Buell on February 25, 1862, two days after Johnston had to pull his forces out to avoid having them captured as well.[97][98][99]

Concentration at Corinth

Johnston was in a perilous situation after the fall of Ft. Donelson and Henry; with barely 17,000 men to face an overwhelming concentration of Union force, he hastily fled south into Mississippi by way of Nashville and then into northern Alabama.[100] Johnston himself retreated with the force under his personal command, the Army of Central Kentucky, from the vicinity of Nashville.[97] With Beauregard's help,[101] Johnston decided to concentrate forces with those formerly under Polk and now already under Beauregard's command at the strategically located railroad crossroads of Corinth, Mississippi, which he reached by a circuitous route.[102] Johnston kept the U.S. forces, now under the overall command of Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, confused and hesitant to move, allowing Johnston to reach his objective undetected.[103] He scraped together reinforcements from Louisiana, as well as part of Polk's force at Island No. 10, and 10,000 additional troops under Braxton Bragg brought up from Mobile.[104] Bragg at least calmed the nerves of Beauregard and Polk, who had become agitated by their apparent dire situation in the face of numerically superior forces, before Johnston's arrival on March 24, 1862.[105][106]

Johnston's army of 17,000 men gave the Confederates a combined force of about 40,000 to 44,669 men at Corinth.[105][101][107] On March 29, 1862, Johnston officially took command of this combined force, which continued to use the Army of the Mississippi name under which Beauregard had organized it on March 5.[108][109]

Johnston's only hope was to crush Grant before Buell and others could reinforce him.[105] He started his army in motion on April 3, intent on surprising Grant's force as soon as the next day. It was not an easy undertaking; his army had been hastily thrown together, two-thirds of the soldiers had never fired a shot in battle, and drill, discipline, and staff work were so poor that the different divisions kept stumbling into each other on the march.[110][111] Beauregard felt that this offensive was a mistake and could not possibly succeed, but Johnston replied "I would fight them if they were a million" as he drove his army on to Pittsburg Landing.[112] His army was finally in position within a mile or two of Grant's force, undetected, by the evening of April 5, 1862.[113][114][115][116][117]

Battle of Shiloh and death

Johnston launched a massive surprise attack with his concentrated forces against Grant at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6, 1862.[118] As the Confederate forces overran the U.S. camps, Johnston personally rallied troops up and down the line on his horse. One of his famous moments in the battle occurred when he witnessed some of his soldiers breaking from the ranks to pillage and loot the U.S. camps and was outraged to see a young lieutenant among them. "None of that, sir", Johnston roared at the officer, "we are not here for plunder." Then, realizing he had embarrassed the man, he picked up a tin cup from a table and announced, "Let this be my share of the spoils today", before directing his army onward.[119]

At about 2:30 pm, while leading one of those charges against a U.S. camp near the "Peach Orchard", he was wounded, taking a bullet behind his right knee. The bullet clipped a part of his popliteal artery, and his boot filled up with blood. No medical personnel were on the scene since Johnston had sent his personal surgeon to care for the wounded Confederate troops and U.S. prisoners earlier in the battle.[120]

Within a few minutes, Johnston was observed by his staff to be nearly fainting. Among his staff was Isham G. Harris, the Governor of Tennessee, who had ceased to make any real effort to function as governor after learning that Abraham Lincoln had appointed Andrew Johnson as military governor of Tennessee. Seeing Johnston slumping in his saddle and his face turning deathly pale, Harris asked: "General, are you wounded?" Johnston glanced down at his leg wound, then faced Harris and said his last words in a weak voice: "Yes... and I fear seriously." Harris and other staff officers removed Johnston from his horse, carried him to a small ravine near the "Hornets Nest", and desperately tried to aid the general, who had lost consciousness. Harris then sent an aide to fetch Johnston's surgeon but did not apply a tourniquet to Johnston's wounded leg. A few minutes later, Johnston died from blood loss before a doctor could be found. It is believed that Johnston may have lived for as long as one hour after receiving his fatal wound. It was later discovered that Johnston had a tourniquet in his pocket when he died.[120]

Harris and the other officers wrapped General Johnston's body in a blanket to not damage the troops' morale with the sight of the dead general. Johnston and his wounded horse, Fire Eater, were taken to his field headquarters on the Corinth road, where his body remained in his tent for the remainder of the battle. P. G. T. Beauregard assumed command of the army. He resumed leading the Confederate assault, which continued advancing and pushed the U.S. forces back to a final defensive line near the Tennessee river. With his army exhausted and daylight almost gone, Beauregard called off the final Confederate attack around 1900 hours, figuring he could finish off the U.S. army the following morning. However, Grant was reinforced by 20,000 fresh troops from Don Carlos Buell's Army of the Ohio during the night and led a successful counter-attack the following day, driving the Confederates from the field and winning the battle. As the Confederate army retreated to Corinth, Johnston's body was taken to the home of Colonel William Inge, which had been his headquarters in Corinth. It was covered in the Confederate flag and lay in state for several hours.[121]

It is possible that a Confederate soldier fired the fatal round, as many Confederates were firing at the U.S. lines while Johnston charged well in advance of his soldiers.[122] Alonzo Ridley of Los Angeles commanded the bodyguard "the Guides" of Gen. A. S. Johnston and was by his side when he fell.[123]

Johnston was the highest-ranking fatality of the war on either side and his death was a strong blow to the morale of the Confederacy. At the time, Davis considered him the best general in the country.[124]

Legacy and honors

Johnston was survived by his wife, Eliza, and six children. His wife and five younger children, including one born after he went to war, chose to live out their days at home in Los Angeles with Eliza's brother, Dr. John Strother Griffin.[125] Johnston's eldest son, Albert Sidney Jr. (born in Texas), had already followed him into the Confederate States Army. In 1863, Albert Jr. was on his way out of San Pedro harbor on a ferry after taking home leave in Los Angeles. While a steamer was taking on passengers from the ferry, a wave swamped the smaller boat, causing its boilers to explode. Albert Jr. was killed in the accident.[126]

Upon his passing, General Johnston received the highest praise ever given by the Confederate government: accounts were published on December 20, 1862, and after that, in the Los Angeles Star of his family's hometown.[127] Johnston Street, Hancock Street, and Griffin Avenue, each in northeast Los Angeles, are named after the general and his family, who lived in the neighborhood.

Johnston was initially buried in New Orleans. In 1866, a joint resolution of the Texas Legislature was passed to have his body moved and reinterred at the Texas State Cemetery in Austin. The re-interment occurred in 1867.[128] Forty years later, the state appointed Elisabet Ney to design a monument and sculpture of him to be erected at the grave site, installed in 1905.[129]

The Texas Historical Commission has erected a historical marker near the entrance of what was once Johnston's plantation. An adjacent marker was erected by the San Jacinto Chapter of the Daughters of The Republic of Texas and the Lee, Roberts, and Davis Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederate States of America.

In 1916, the University of Texas at Austin recognized several confederate veterans (including Johnston) with statues on its South Mall. On August 21, 2017, as part of the wave of confederate monument removals in America, Johnston's statue was taken down. Plans were announced to add it to the Briscoe Center for American History on the east side of the university campus.[130]

Johnston was inducted to the Texas Military Hall of Honor in 1980.[131]

In the fall of 2018, A. S. Johnston Elementary School in Dallas, Texas, was renamed Cedar Crest Elementary. Johnston Middle School in Houston, Texas, was also renamed Meyerland Middle School. Three other elementary schools named for Confederate veterans were renamed simultaneously.[132]

See also

- Albert Sidney Johnston High School, a defunct public high school in Austin, Texas

- Statue of Albert Sidney Johnston (Texas State Cemetery), a 1903 memorial sculpture by Elisabet Ney

- Statue of Albert Sidney Johnston (University of Texas at Austin), a statue by Pompeo Coppini

- List of American Civil War generals (Confederate)

- List of Confederate monuments and memorials

Notes

- ^ Glaze, Robert L. (April 2, 2021), Albert Sidney Johnston Confederate general, Britannica, retrieved October 26, 2021

- ^ a b Woodworth, p. 46.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chisholm, p. 472

- ^ Eicher, p. 322.

- ^ Johnston, William Preston (1878). The Life of General Albert Sidney Johnston: Embracing his Services in the Armies of the United States, the Republic of Texas, and the Confederate States. New York: Appleton and Company. pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b Roland, pp. 46

- ^ "W.P. Johnston biography". Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ "Dueling, and The Huston-Johnston Duel in Feb. 5, 1837".

- ^ Johnston, pp. 80

- ^ Truman, Ben C. (1908). "Albert Sidney Johnston's Duel". Confederate Veteran Magazine. XVI: 461.

- ^ Wylie, Arthur (2016). The Battles and Men of the Republic of Texas. Lulu Press. p. 44.

- ^ Taylor, Richard (1879). Destruction and Reconstruction: Personal Experiences of the Late War. New York: Appleton and Company. p. 232.

- ^ Blaine, James Gillespie, Twenty Years of Congress, Vol. 1, Ch. 4.

- ^ Johnston, pp. 185

- ^ Shaw, Arthur M. (1942). "Albert Sidney Johnston in Texas: Letters to Relatives in Kentucky, 1847–1860". Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society. 40 (132): 290–317.

- ^ Johnston, pp. 211

- ^ Roland, pp. 202

- ^ Deseret News (1858). Edition published October 13, 1858, Salt Lake City, Utah Territory.

- ^ Johnston, pp. 239

- ^ MacKinnon, William P. (2008). At Sword's Point: A documentary history of the Utah War, 1858–1859. California: Arthur H. Clark Company. p. 171.

- ^ Johnston, p. 235

- ^ Senate of the United States; First Session of the 36th Congress, 1859–60; No. 42, p. 26

- ^ Wilson, pp. 165

- ^ Roland, p. 141.

- ^ Roland, p. 166.

- ^ Roland, p. 182.

- ^ Roland, p. 242.

- ^ Johnston, p. 273.

- ^ "'Horrible Catastrophe!'". Los Angeles Star. Vol. XII, No. 52, May 2, 1863.

- ^ Johnston, pp. 185.

- ^ ""Californians in the Confederate Service,"". Los Angeles Star, Vol. XIII, No. 32, December 12, 1863.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 17–33.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 20–22

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 35, 45.

- ^ Long, p. 114.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 39, 50.

- ^ Woodworth, p. 39.

- ^ Long, p. 115.

- ^ a b Woodworth, p. 51.

- ^ Long, p. 116.

- ^ Eicher, Civil War High Commands. p. 807. From General Command Line List. Weigley, p. 110. McPherson, p. 394.

- ^ a b c Woodworth, p. 52.

- ^ Long, p. 119.

- ^ a b c Woodworth, p. 53.

- ^ a b Woodworth, p. 55.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 55–56

- ^ Long, p. 138.

- ^ McPherson, p. 394 says Johnston had 70,000 troops to defend his territory between the Appalachians and the Ozarks by the end of 1861.

- ^ The Memoirs of General W. T. Sherman (1885), Chapter IX https://www.gutenberg.org/files/4361/4361-h/4361-h.htm

- ^ Woodworth, p. 61

- ^ Woodworth, p. 65.

- ^ Long, pp. 161–162.

- ^ a b Woodworth, p. 66.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Woodworth, p. 67.

- ^ Long, p. 162.

- ^ Woodworth, p. 69.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 80, 84.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 72, 78.

- ^ Woodworth, p. 54.

- ^ Eicher, The Longest Night. pp. 111–113.

- ^ a b c d Woodworth, p. 56.

- ^ a b Long, p. 142

- ^ Weigley, p. 108

- ^ McPherson, p. 393.

- ^ a b c Woodworth, p. 57.

- ^ Woodworth, p. 58.

- ^ Long, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Eicher, The Longest Night, p. 171 says the garrison at Fort Donelson numbered 1,956 men before the Fort Henry garrison and the men under Floyd and Pillow joined them in early February 1862.

- ^ a b Woodworth, p. 71.

- ^ McPherson, p. 396.

- ^ A Confederate battery and the beginning of some fortifications were sited across the river at Fort Heiman, but these were of little value when the U.S. flotilla appeared.

- ^ Woodworth, p. 78.

- ^ After some preliminary work with Johnston, Beauregard assumed command of this force, which he named the Army of the Mississippi, on March 5, 1862, while at Jackson, Tennessee. Like the other Confederate commander, he had to withdraw to the south after the fall of the forts or be surrounded by the advancing U.S. forces. Long, p. 178.

- ^ a b Woodworth, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Long, p. 167.

- ^ Long, pp. 166–167

- ^ Weigley, p. 109.

- ^ a b Woodworth, p. 79.

- ^ Loing, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Woodworth, p. 80.

- ^ McPherson, pp. 400–401.

- ^ Floyd was able to ferry his four Virginia regiments out of the fort with him but left his Mississippi regiment behind to surrender with the rest of the garrison. Pillow escaped only with his chief of staff. Woodworth, p. 83. Long, p. 171.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 82–84.

- ^ Woodworth, p. 84.

- ^ McPherson, pp. 401–402.

- ^ This included about 200 men not in Forrest's immediate command. Weigley, p. 111

- ^ Long, p. 172.

- ^ a b Weigley, p. 111.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Weigley, p. 112.

- ^ McPherson, pp. 405–406.

- ^ Davis defended Johnston, saying: "If Sidney Johnston is not a general, we had better give up the war, for we have no general." McPherson, p. 495.

- ^ a b Woodworth, p. 86.

- ^ Long, p. 175.

- ^ McPherson, p. 402.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b McPherson, p. 406.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 86–88.

- ^ Woodworth, p. 88.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 90, 94.

- ^ a b c Woodworth, p. 95.

- ^ Long, p. 188.

- ^ Eicher, The Longest Night, p. 223.

- ^ Long, 190.

- ^ Eicher, Civil War High Commands p. 887 and Eicher, The Longest Night p. 219 are nearly alone in referring to this army as the Army of Mississippi. Muir, p. 85, in discussing the first "Army of Mississippi", includes this army as one of three in the article with that title but states: "Historians have pointed out that the Army of Mississippi is frequently mentioned in the Official Records as the Army of the Mississippi." Contemporaries, including Johnston and Beauregard, and modern historians call this Confederate army the Army of the Mississippi. "'The war of the rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies.'"., Volume X, Part 1, index, pp. 96–99; 385 (Beauregard's report on the Battle of Shiloh, April 11, 1862, from Headquarters, Army of the Mississippi) and Part 2, p. 297 (Beauregard's announcement on taking command of Army of the Mississippi); p. 370 (Johnston General Orders of March 29, 1862, assuming command and announcing the army would retain the name Army of the Mississippi); pp. 405–409. Beauregard, p. 579. Boritt, p. 53. Connelly, Army of the Heartland: The Army of Tennessee, 1861–1862. p. 151. ("The Army retained Beauregard's chosen name...") Connelly, Civil War Tennessee: Battles And Leaders. p. 35. Cunningham, pp. 98, 122, 397. Engle, p. 123. Hattaway, p. 163. Hess, pp. 47, 49, 112 ("...Braxton Bragg's renamed Army of Tennessee (formerly the Army of the Mississippi)..."). Isbell, p. 102. McDonough, pp. 60, 66, 78. Kennedy, p. 48. Noe, p. 19. Williams, p. 122.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Long, p. 192

- ^ McWhiney; Jamieson, p. 162.

- ^ Woodworth, p. 97.

- ^ Long, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Weigley, p. 113.

- ^ McPherson, pp. 406–407.

- ^ Johnston did not achieve total surprise as some U.S. pickets were alerted to the Confederate presence and provided warning to some U.S. units before the attack began.

- ^ Chisholm, p. 473

- ^ "CMH Remembers the Battle of Shiloh | CMH".

- ^ a b "Battlefield Tours: Full Tour Shiloh". Civil War Landscapes Association. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ^ Sword, pp. 270–273, 443–446; Cunningham, pp. 273–276; Smith, pp. 26–34. Sword offers evidence that Johnston lived as long as an hour after receiving his fatal wound.

- ^ Sword, p. 444.

- ^ "'From Rebeldom,'". Los Angeles Star, Vol. XII, No. 30, November 29, 1862.

- ^ Dupuy, p. 378.

- ^ "Johnston, Eliza Griffin". Texas State Historical Association. June 15, 2010.

- ^ "Los Angeles Star, vol. 13, no. 2, May 16, 1863".

- ^ "Los Angeles Star, vol. 12, no. 33, December 20, 1862".

- ^ Cartwright, Gary (May 2008). "Remains of the Day". Texas Monthly. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ "Albert Sidney Johnston". Texas State Cemetery. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ "Confederate Statues on Campus" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 21, 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ "Hall of Honor". Texas Military Forces Museum.

- ^ Smith, Corbett (June 13, 2018). "See ya, Stonewall: Dallas ISD begins to remove Confederate leaders' names from 4 schools". DallasNews.com. The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

References

- Beauregard, G. T. The Campaign of Shiloh. p. 579. In Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. I, edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence C. Buel. New York: Century Co., 1884–1888. OCLC 2048818.

- G. S. Boritt (1999). Jefferson Davis' Generals. Oxford University Press on Demand. ISBN 978-0-19-512062-2.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 472–473.

- Thomas Lawrence Connelly (2001). Army of the Heartland: The Army of Tennessee, 1861–1862. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2737-7.

- Thomas Lawrence Connelly (1979). Civil War Tennessee: battles and leaders. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0-87049-284-6.

- O. Edward Cunningham (2007). Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862. Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-932714-27-2.

- Dupuy, Trevor N., Curt Johnson, and David L. Bongard. Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography. New York: HarperCollins, 1992. ISBN 978-0-06-270015-5.

- David J. Eicher (2001). The longest night: a military history of the Civil War. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Civil War high commands. Stanford University Press. 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Stephen Douglas Engle; Bison Book (2005). Struggle for the Heartland: The Campaigns From Fort Henry To Corinth. Bison Books. ISBN 978-0-8032-6753-4.

- Hattaway, Herman, and Archer Jones. How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983. ISBN 0-252-00918-5.

- Earl J. Hess (2012). The Civil War in the West: Victory and Defeat from the Appalachians to the Mississippi. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3542-5.

- Shiloh and Corinth: Sentinels of Stone. University Press of Mississippi. 2007. ISBN 978-1-934110-08-9.

- William Preston Johnston (1878). The life of Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston: embracing his services in the armies of the United States, the republic of Texas, and the Confederate States. D. Appleton.

- Frances H. Kennedy; Conservation Fund (Arlington, Va) (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Long, E. B. The Civil War Day by Day: An Almanac, 1861–1865. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971. OCLC 68283123.

- James Lee McDonough (1977). Shiloh, in Hell Before Night. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0-87049-199-3.

- McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York : Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503863-7.

- David Stephen Heidler; Jeanne T. Heidler; David J. Coles (2002). Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04758-5.

- Noe, Kenneth (2001). Perryville. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2209-0.

- Smith, Derek (2005). The Gallant Dead: Union and Confederate Generals Killed in the Civil War. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0132-7.

- Sword, Wiley (1992). The Confederacy's Last Hurrah: Spring Hill, Franklin, and Nashville. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0650-4.

- Russell F. Weigley (2000). A great Civil War: a military and political history, 1861–1865. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33738-2.

- T. Harry Williams (1995). P. G. T. Beauregard: Napoleon in Gray. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-1974-7.

- Woodworth, Steven E. (1990). Jefferson Davis and His Generals: the Failure of Confederate Command in the West. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0461-8.

- McWhiney, Grady; Jamieson, Perry D. (1984). Attack and Die: Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0229-0. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- Roland, Charles Pierce (1964). Albert Sidney Johnston: Soldier of Three Republics. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-9000-6.

Further reading

- Larry J. Daniel (1997). Shiloh: the battle that changed the Civil War. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80375-5.

- Kendall D. Gott (2003). Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry-Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0049-8.

- Albert A. Nofi (2001). The Alamo: And the Texas War for Independence September 30, 1835 to April 21, 1836 : Heroes, Myths and History. Hachette Books. ISBN 978-0-306-81040-4.

- Charles Pierce Roland (2000). Jefferson Davis's Greatest General: Albert Sidney Johnston. McWhiney Foundation Press. ISBN 1-893114-20-1.

External links

![]() Media related to Albert Sidney Johnston at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Albert Sidney Johnston at Wikimedia Commons

- Eliza Johnston, Wife Of Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston

- Albert Sidney Johnston at Handbook of Texas Online

- Albert Sidney Johnston Collection finding aid at University of Texas at Arlington Libraries Special Collections via Texas Archival Resources Online (TARO)