Contents

The Battle of Galveston Harbor was fought at Galveston, Texas on October 4, 1862, during the American Civil War. After attempts to blockade the Texas coastline were unsuccessful, the Union Navy decided to attempt to capture the port of Galveston. While Galveston was defended by Confederate forces, most of the cannons in the city's defenses were removed, as Galveston was thought to be indefensible. On October 4, five Union naval vessels commanded by Commander William B. Renshaw approached Galveston, and a single ship, USRC Harriet Lane was sent into Galveston Bay under a flag of truce.

The Confederates, commanded by Colonel Joseph J. Cook, could not get a boat to Harriet Lane in a timely manner, and the Union ship left the bay. The Confederate boat headed for the Union fleet, which moved towards the bay under flags of truce to meet it. Misunderstandings led to artillery fire, although a four-day truce was eventually made. The terms of the truce were unclear, and the Confederates used the truce to evacuate the city, which was initially objected to by Renshaw. At the expiration of the truce, Union troops landed in Galveston and raised the United States flag over the city. The Confederates recaptured Galveston on January 1, 1863, in the Battle of Galveston. The battlefield has lost historical integrity due to development and changes in the shoreline.

Background

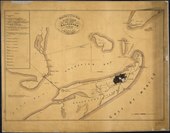

When the American Civil War began in April 1861, President of the United States Abraham Lincoln declared a naval blockade of the coastline and ports of the Confederate States of America, with the goal of cutting the Confederates off from foreign trade. At the time, the most significant port on the Texas portion of the Confederate coastline was Galveston. After the blockade order was issued, Union Navy ships were sent to the Texas coast, but the blockade was not immediately effective. Under international law of the time, a blockade needed to be effective in order to be legal, and in December, HMS Desperate visited Galveston and saw no US Navy presence. William McKean, commander of the Gulf Blockading Squadron, doubted the accuracy of the British report but forwarded the information to the United States Secretary of the Navy.[1] Because of the shape of Galveston Bay, blockading the port would require at least two ships.[2]

Under the supervision of Major General John B. Magruder, Confederate forces under W. W. Hunter had been placing artillery batteries, digging trenches, and obstructed harbor channels to ready the defense of Galveston. The defenses were not particularly imposing, though, and Confederate officer Xavier Debray wrote in a letter than the city was not defensible.[3] The Union blockade still struggled with ineffectiveness, and the decision was made to capture some Confederate ports in order provide more bases for Union ships and fewer for blockade runners.[4] On May 17, 1862, the captain of the USS Santee sailed to Galveston, and demanded the surrender of the town, threatening to begin bombarding the place on May 23; the threatened attack did not occur.[5] In August, Union Admiral David Glasgow Farragut ordered Commander William B. Renshaw[6] to destroy blockade runners and capture Galveston if practicable.[4]

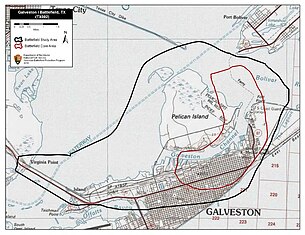

Galveston Island itself was defended by a single artillery regiment, under the command of Colonel Joseph J. Cook. The island was connected to the mainland by a bridge, which had a terminus on the mainland at a place known as Virginia Point. Union intelligence believed that Virginia Point was strongly defended, but it was not. Confederate defenses at Fort Point, which commanded the northern entrance to Galveston Bay, were also weak. Confederate naval forces near Galveston were negligible. Additional Confederate troops were in the Houston area and along the rail line between Houston and Galveston, bringing the total number of Confederate troops in the region to about 5,000.[2] Many of the cannons in the city's defenses had been removed, as Confederate Brigadier General Paul Octave Hébert believed the city was indefensible.[7]

Battle

Renshaw moved towards Galveston with five ships[a] and approached the city by early October.[5][2][8] The five Union ships were USS Westfield (the expedition's flagship), USRC Harriet Lane, USS Owasco, USS Clifton, and the mortar schooner USS Henry Janes.[9] Westfield and Clifton were sidewheel steamers converted from ferry boats,[10][11] Harriet Lane was also a sidewheel steamer,[12] and Owasco was a screw steamer serving as a gunboat.[13] Harriet Lane was sent into Galveston Bay early on October 4, with a flag of truce. After waiting in vain for Confederate messengers to reach the ship and reply, a boat of officers from Harriet Lane was sent to shore, where they met with Cook, who agreed to send a delegation to the Union fleet to discuss surrender terms. Cook's men had difficult finding a boat, and were delayed until 13:00.[14] By then, Lieutenant Commander Jonathan Mayhew Wainwright, commanding Harriet Lane,[15] had become impatient and left Galveston Bay.[14]

The approaching Confederate boat was visible to Renshaw's fleet outside of the bay, and the Union vessels began to move into the bay, visibly flying flags of truce. A Confederate cannon on Fort Point fired a warning shot across the bow of one of the Union vessels,[7] which was interpreted by the Union fleet as a hostile action. Union return fire quickly knocked the single Confederate cannon at Fort Point out of action,[7] while Confederate artillery at Galveston fired on the Union vessels, despite the range being too far to be effective.[16]

The Union ships were still flying truce flags while firing, and Renshaw realized that continue to fire would be against the laws of war, so he ordered the ships to cease fire. Both Renshaw and Cook believed that the other side's shots had represented deliberate hostile actions.[17] Cook's messengers reached and boarded Westfield,[8] and Renshaw demanded immediate surrender, and threatened a further attack if it was not agreed to. The Confederates declined and reminded that Renshaw would be responsible for any damage to private property or civilian fatalities in the case of an attack.[17]

The two sides formed a verbal agreement for a four-day truce. The terms were that the Union vessels would not get any closer to Galveston, and that the Confederates would not work on new or existing fortifications. The verbal truce was interpreted differently: Renshaw thought that it guaranteed the military status quo would remain, while Cook thought he had the option of evacuating Galveston. As a result, the Confederates used the truce to evacuate supplies and cannons from the city. Renshaw thought that the Confederates were purposefully violating the terms of the truce, but after contacting Cook and hearing his explanation, accepted the removal of the material; it was of low value and Renshaw believed he could not prevent the Confederates from removing the cannons anyway.[18]

After the truce ended, Renshaw ordered three signal shots fired, and the mayor and city council of Galveston traveled to Westfield and surrendered the city. A detachment of 150 men led by the commander of Harriet Lane raised the United States flag over the city,[19] as there were no longer any Confederate defenders there.[20] The only cannon the Confederates had left behind was the one disabled during the October 4 bombardment; several fake cannons known as Quaker guns were left in the abandoned defenses.[15] The National Park Service states that there were no casualties incurred during the action,[8] while the Civil War Battlefield Guide states that casualties are unknown.[21]

Aftermath

Shortly after Galveston fell, the Union Navy was able to gain control of the waters outside of Corpus Christi and Sabine City, leading to Union control of most of the Texas coastline.[20] Lack of cooperation from Major General Benjamin F. Butler resulted in difficulties in getting Union infantry to hold Galveston. Two minor incidents in November also resulted in the capture of small detachments from Henry Janes and Owasco.[22] An infantry garrison finally arrived on December 25 in the form of 264 men from the 42nd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment.[23] On January 1, 1863, a Confederate force under Magruder attacked Galveston and defeated the Union forces defending it in the Battle of Galveston. Renshaw was killed by an explosion while scuttling Westfield, and Harriet Lane was captured; the Confederates regained control of Galveston.[24] A 2010 study by the American Battlefield Protection Program noted that development from Galveston and changes to shorelines mean that the current landscape does not resemble the landscape present during the war, and that the site does not retain historical integrity.[25]

Notes

References

- ^ Cumberland 1947, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b c Cumberland 1947, p. 111.

- ^ Trexler 1931, pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b Cumberland 1947, p. 110.

- ^ a b Trexler 1931, p. 113.

- ^ Frazier 1995, p. 175.

- ^ a b c d Barr 1961, p. 13.

- ^ a b c "Galveston I". National Park Service. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ Tucker 2005, p. 137.

- ^ "Westfield". DANFS. Naval History and Heritage Command. October 27, 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ "Clifton". DANFS. Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ "Harriet Lane". DANFS. Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ "Owasco". DANFS. Naval History and Heritage Command. August 18, 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ a b Cumberland 1947, pp. 111–112.

- ^ a b Howell 2009, p. 117.

- ^ Cumberland 1947, p. 112.

- ^ a b Cumberland 1947, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Cumberland 1947, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Howell 2009, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b Cumberland 1947, p. 115.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, p. 138.

- ^ Cumberland 1947, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Barr, Alwyn. "Galveston, Battle of". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 138–139.

- ^ American Battlefield Protection Program 2010, p. 5.

Sources

- Barr, Alwyn (July 1961). "Texas Coastal Defense, 1861–1865". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 65 (1): 1–31. JSTOR 30236188.

- Cumberland, Charles C. (October 1947). "The Confederate Loss and Recapture of Galveston, 1862–1863". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 51 (2): 109–130. JSTOR 30236128.

- Frazier, Donald S. (October 1995). "Sibley's Texans and the Battle of Galveston". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 99 (2): 174–198. JSTOR 30239013.

- Howell, Kenneth Wayne (2009). The Seventh Star of the Confederacy: Texas During the Civil War. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas Press. ISBN 9781574412598.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Trexler, H. A. (October 1931). "The "Harriet Lane" and the Blockade of Galveston". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 35 (2): 109–123. JSTOR 0235394.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2005) [2002]. A Short History of the Civil War at Sea. Lanham, Maryland: Scholarly Resources. ISBN 9780842028684.

- "Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation's Civil War Battlefields: State of Texas" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: American Battlefield Protection Program. May 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2021.