Contents

Sycorax /ˈsɪkɒræks/ is the largest irregular satellite of Uranus. Sycorax was discovered on 6 September 1997 by Brett J. Gladman, Philip D. Nicholson, Joseph A. Burns, and John J. Kavelaars using the 200-inch Hale telescope, together with Caliban, and given the temporary designation S/1997 U 2.[1]

Officially confirmed as Uranus XVII, it was named after Sycorax, Caliban's mother in William Shakespeare's play The Tempest.

Orbit

Uranus · Sycorax · Francisco · Caliban · Stephano · Trinculo

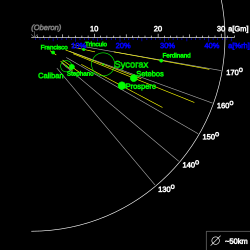

Sycorax follows a distant orbit, more than 20 times further from Uranus than the furthest regular moon, Oberon.[1] Its orbit is retrograde, moderately inclined and eccentric. The orbital parameters suggest that it may belong, together with Setebos and Prospero, to the same dynamic cluster, suggesting common origin.[11]

The diagram illustrates the orbital parameters of the retrograde irregular satellites of Uranus (in polar co-ordinates) with the eccentricity of the orbits represented by the segments extending from the pericentre to the apocentre.

Physical characteristics

The diameter of Sycorax is estimated at 165 km based on the thermal emission data from Spitzer and Herschel Space telescopes[8] making it the largest irregular satellite of Uranus, comparable in size with Puck and with Himalia, the biggest irregular satellite of Jupiter.

The satellite appears light-red in the visible spectrum (colour indices B–V = 0.87 V–R = 0.44,[12] B–V = 0.78 ± 0.02 V–R = 0.62 ± 0.01,[11] B–V = 0.839 ± 0.014 V–R = 0.531 ± 0.005[9]), redder than Himalia but still less red than most Kuiper belt objects. However, in the near infrared, the spectrum turns blue between 0.8 and 1.25 μm[clarification needed] and finally becomes neutral at the longer wavelengths.[10]

The rotation period of Sycorax is estimated at about 6.9 hours.[7] Rotation causes periodical variations of the visible magnitude with the amplitude of 0.12.[7] The rotation axis of Sycorax is unknown, though measurements of its light curve suggest it is being viewed at a near equator-on configuration. In this case, Sycorax may have a north pole right ascension around 356° and a north pole declination around 45°.[7]

Origin

It is hypothesized that Sycorax is a captured object; it did not form in the accretion disk which existed around Uranus just after its formation. No exact capture mechanism is known, but capturing a moon requires the dissipation of energy. Possible capture processes include gas drag in the protoplanetary disk and many-body interactions and capture during the fast growth of Uranus's mass (so-called pull-down).[13][9]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Gladman Nicholson et al. 1998.

- ^ Shakespeare Recording Society (1995) The Tempest (audio CD)

- ^ Benjamin Smith (1903) The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia

- ^ Goldberg (2004) Tempest in the Caribbean

- ^ "M.P.C. 102109" (PDF). Minor Planet Circular. Minor Planet Center. 14 November 2016.

- ^ a b c

Jacobson, R.A. (2003) URA067 (2007-06-28). "Planetary Satellite Mean Orbital Parameters". JPL/NASA. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Farkas-Takács, A.; Kiss, Cs.; Pál, A.; Molnár, L.; Szabó, Gy. M.; Hanyecz, O.; et al. (September 2017). "Properties of the Irregular Satellite System around Uranus Inferred from K2, Herschel, and Spitzer Observations". The Astronomical Journal. 154 (3): 13. arXiv:1706.06837. Bibcode:2017AJ....154..119F. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa8365. S2CID 118869078. 119.

- ^ a b c d Lellouch, E.; Santos-Sanz, P.; Lacerda, P.; Mommert, M.; Duffard, R.; Ortiz, J. L.; Müller, T. G.; Fornasier, S.; Stansberry, J.; Kiss, Cs.; Vilenius, E.; Mueller, M.; Peixinho, N.; Moreno, R.; Groussin, O.; Delsanti, A.; Harris, A. W. (September 2013). ""TNOs are Cool": A survey of the trans-Neptunian region. IX. Thermal properties of Kuiper belt objects and Centaurs from combined Herschel and Spitzer observations" (PDF). Astronomy & Astrophysics. 557: A60. arXiv:1202.3657. Bibcode:2013A&A...557A..60L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322047. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ a b c Maris, Michele; Carraro, Giovanni; Parisi, M.G. (2007). "Light curves and colours of the faint Uranian irregular satellites Sycorax, Prospero, Stephano, Setebos, and Trinculo". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 472 (1): 311–319. arXiv:0704.2187. Bibcode:2007A&A...472..311M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066927. S2CID 12362256.

- ^ a b Romon, J.; de Bergh, C.; et al. (2001). "Photometric and spectroscopic observations of Sycorax, satellite of Uranus". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 376 (1): 310–315. Bibcode:2001A&A...376..310R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20010934.

- ^ a b Grav, Holman & Fraser 2004.

- ^ Rettig, Walsh & Consolmagno 2001.

- ^ Sheppard, Jewitt & Kleyna 2005.

- Gladman, B. J.; Nicholson, P. D.; Burns, J. A.; Kavelaars, J. J.; Marsden, B. G.; Williams, G. V.; Offutt, W. B. (1998). "Discovery of two distant irregular moons of Uranus". Nature. 392 (6679): 897–899. Bibcode:1998Natur.392..897G. doi:10.1038/31890. S2CID 4315601.

- Grav, Tommy; Holman, Matthew J.; Fraser, Wesley C. (2004-09-20). "Photometry of Irregular Satellites of Uranus and Neptune". The Astrophysical Journal. 613 (1): L77–L80. arXiv:astro-ph/0405605. Bibcode:2004ApJ...613L..77G. doi:10.1086/424997. S2CID 15706906.

- Sheppard, S. S.; Jewitt, D.; Kleyna, J. (2005). "An Ultradeep Survey for Irregular Satellites of Uranus: Limits to Completeness". The Astronomical Journal. 129 (1): 518–525. arXiv:astro-ph/0410059. Bibcode:2005AJ....129..518S. doi:10.1086/426329. S2CID 18688556.

- Rettig, T. W.; Walsh, K.; Consolmagno, G. (December 2001). "Implied Evolutionary Differences of the Jovian Irregular Satellites from a BVR Color Survey". Icarus. 154 (2): 313–320. Bibcode:2001Icar..154..313R. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6715.