Contents

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

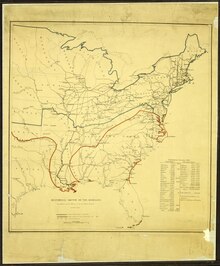

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required the monitoring of 3,500 miles (5,600 km) of Atlantic and Gulf coastline, including 12 major ports, notably New Orleans and Mobile. Those blockade runners fast enough to evade the Union Navy could carry only a small fraction of the supplies needed. They were operated largely by British citizens, making use of neutral ports such as Havana, Nassau and Bermuda. The Union commissioned around 500 ships, which destroyed or captured about 1,500 blockade runners over the course of the war.

The blockade was largely successful in reducing 95% of cotton export in the South from pre-war levels, devaluing its currency and severely damaging its economy. However, it was less successful in preventing war material from being smuggled into the South. Throughout the conflict, at least 600,000 arms (mostly British Pattern 1853 Enfield rifles)[1] were smuggled by blockade runners to the Confederacy, 330,000 of them into the Gulf ports.[2] Historians have estimated that supplies brought to the Confederacy via blockade runners that made it past the Union blockade lengthened the duration of the conflict by up to two years.[3][4][5]

Proclamation of blockade

On April 19, 1861, President Lincoln issued a Proclamation of Blockade Against Southern Ports:[6]

Whereas an insurrection against the Government of the United States has broken out in the States of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas, and the laws of the United States for the collection of the revenue cannot be effectually executed therein comformably to that provision of the Constitution which requires duties to be uniform throughout the United States:

And whereas a combination of persons engaged in such insurrection, have threatened to grant pretended letters of marque to authorize the bearers thereof to commit assaults on the lives, vessels, and property of good citizens of the country lawfully engaged in commerce on the high seas, and in waters of the United States: And whereas an Executive Proclamation has been already issued, requiring the persons engaged in these disorderly proceedings to desist therefrom, calling out a militia force for the purpose of repressing the same, and convening Congress in extraordinary session, to deliberate and determine thereon:

Now, therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, with a view to the same purposes before mentioned, and to the protection of the public peace, and the lives and property of quiet and orderly citizens pursuing their lawful occupations, until Congress shall have assembled and deliberated on the said unlawful proceedings, or until the same shall ceased, have further deemed it advisable to set on foot a blockade of the ports within the States aforesaid, in pursuance of the laws of the United States, and of the law of Nations, in such case provided. For this purpose a competent force will be posted so as to prevent entrance and exit of vessels from the ports aforesaid. If, therefore, with a view to violate such blockade, a vessel shall approach, or shall attempt to leave either of the said ports, she will be duly warned by the Commander of one of the blockading vessels, who will endorse on her register the fact and date of such warning, and if the same vessel shall again attempt to enter or leave the blockaded port, she will be captured and sent to the nearest convenient port, for such proceedings against her and her cargo as prize, as may be deemed advisable.

And I hereby proclaim and declare that if any person, under the pretended authority of the said States, or under any other pretense, shall molest a vessel of the United States, or the persons or cargo on board of her, such person will be held amenable to the laws of the United States for the prevention and punishment of piracy.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand, and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this nineteenth day of April, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-one, and of the Independence of the United States the eighty-fifth.

Operations

Scope

A joint Union military-navy commission, known as the Blockade Strategy Board, was formed to make plans for seizing major Southern ports to utilize as Union bases of operations to expand the blockade. It first met in June 1861 in Washington, D.C., under the leadership of Captain Samuel F. Du Pont.[7]

In the initial phase of the blockade, Union forces concentrated on the Atlantic Coast. The November 1861 capture of Port Royal in South Carolina provided the Federals with an open ocean port and repair and maintenance facilities in good operating condition. It became an early base of operations for further expansion of the blockade along the Atlantic coastline,[8] including the Stone Fleet of old ships deliberately sunk to block approaches to Charleston, South Carolina. Apalachicola, Florida, received Confederate goods traveling down the Chattahoochee River from Columbus, Georgia, and was an early target of Union blockade efforts on Florida's Gulf Coast.[9] Another early prize was Ship Island, which gave the Navy a base from which to patrol the entrances to both the Mississippi River and Mobile Bay. The Navy gradually extended its reach throughout the Gulf of Mexico to the Texas coastline, including Galveston and Sabine Pass.[10]

With 3,500 miles (5,600 km) of Confederate coastline and 180 possible ports of entry to patrol, the blockade would be the largest such effort ever attempted. The United States Navy had 42 ships in active service, and another 48 laid up and listed as available as soon as crews could be assembled and trained. Half were sailing ships, some were technologically outdated, most were at the time patrolling distant oceans, one served on Lake Erie and could not be moved into the ocean, and another had gone missing off Hawaii.[11] At the time of the declaration of the blockade, the Union only had three ships suitable for blockade duty. The Navy Department, under the leadership of Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, quickly moved to expand the fleet. U.S. warships patrolling abroad were recalled, a massive shipbuilding program was launched, civilian merchant and passenger ships were purchased for naval service, and captured blockade runners were commissioned into the navy. In 1861, nearly 80 steamers and 60 sailing ships were added to the fleet, and the number of blockading vessels rose to 160. Some 52 more warships were under construction by the end of the year.[12][13] By November 1862, there were 282 steamers and 102 sailing ships.[14] By the end of the war, the Union Navy had grown to a size of 671 ships, making it the largest navy in the world.[15]

By the end of 1861, the Navy had grown to 24,000 officers and enlisted men, over 15,000 more than in antebellum service. Four squadrons of ships were deployed, two in the Atlantic and two in the Gulf of Mexico.[16]

Blockade service

Blockade service was attractive to Federal seamen and landsmen alike. Blockade station service was considered the most boring job in the war but also the most attractive in terms of potential financial gain. The task was for the fleet to sail back and forth to intercept any blockade runners. More than 50,000 men volunteered for the boring duty, because food and living conditions on ship were much better than the infantry offered, the work was safer, and especially because of the real (albeit small) chance for big money. Captured ships and their cargoes were sold at auction and the proceeds split among the sailors. When Eolus seized the hapless blockade runner Hope off Wilmington, North Carolina, in late 1864, the captain won $13,000 ($253,251 today), the chief engineer $6,700, the seamen more than $1,000 each, and the cabin boy $533, compared to infantry pay of $13 ($253 today) per month.[17] The amount garnered for a prize of war widely varied. While the little Alligator sold for only $50, bagging the Memphis brought in $510,000 ($9,935,234 today) (about what 40 civilian workers could earn in a lifetime of work). In four years, $25 million in prize money ($487,021,277 today) was awarded.

Blockade runners

While a large proportion of blockade runners did manage to evade the Union ships,[18] as the blockade matured, the type of ship most likely to find success in evading the naval cordon was a small, light ship with a short draft—qualities that facilitated blockade running but were poorly suited to carrying large amounts of heavy weaponry, metals, and other supplies badly needed by the South. They were also useless for exporting the large quantities of cotton that the South needed to sustain its economy.[19] To be successful in helping the Confederacy, a blockade runner had to make many trips; eventually, most were captured or sunk. Nonetheless, five out of six attempts to evade the Union blockade were successful. During the war, some 1,500 blockade runners were captured or destroyed.[18]

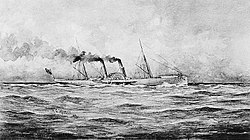

Ordinary freighters were too slow and visible to escape the Navy. The blockade runners therefore relied mainly on new steamships built in Britain with low profiles, shallow draft, and high speed. Their paddle-wheels, driven by steam engines that burned smokeless anthracite coal, could make 17 kn (31 km/h; 20 mph). Because the South lacked sufficient sailors, skippers and shipbuilding capability, the runners were mostly built, commanded and manned of officers and sailors of the British Merchant Marine.[20] The profits from blockade running were high as a typical blockade runner could make a profit equal to about $1 million U.S. dollars in 1981 values from a single voyage.[20] Private British investors spent perhaps £50 million on the runners ($250 million in U.S. dollars, equivalent to about $2.5 billion in 2006 dollars). The pay was high: a Royal Navy officer on leave might earn several thousand dollars (in gold) in salary and bonus per round trip, with ordinary seamen earning several hundred dollars.

The blockade runners were based in the British islands of Bermuda and the Bahamas, or Havana, in Spanish Cuba. The goods they carried were brought to these places by ordinary cargo ships, and loaded onto the runners. The runners then ran the gauntlet between their bases and Confederate ports, some 500–700 mi (800–1,130 km) apart. On each trip, a runner carried several hundred tons of compact, high-value cargo such as cotton, turpentine or tobacco outbound, and rifles, medicine, brandy, lingerie and coffee inbound. Often they also carried mail. They charged from $300 to $1,000 per ton of cargo brought in; two round trips a month would generate perhaps $250,000 in revenue (and $80,000 in wages and expenses).

Blockade runners preferred to run past the Union Navy at night, either on moonless nights, before the moon rose, or after it set. As they approached the coastline, the ships showed no lights, and sailors were prohibited from smoking. Likewise, Union warships covered all their lights, except perhaps a faint light on the commander's ship. If a Union warship discovered a blockade runner, it fired signal rockets in the direction of its course to alert other ships. The runners adapted to such tactics by firing their own rockets in different directions to confuse Union warships.[21]

In November 1864, a wholesaler in Wilmington asked his agent in the Bahamas to stop sending so much chloroform and instead send "essence of cognac" because that perfume would sell "quite high". Confederate supporters held rich blockade runners in contempt for profiteering on luxuries while the soldiers were in rags. On the other hand, their bravery and initiative were necessary for the rebellion's survival, and many women in the back country flaunted imported $10 gewgaws and $50 hats to demonstrate the Union had failed to isolate them from the outer world. The government in Richmond, Virginia, eventually regulated the traffic, requiring half the imports to be munitions; it even purchased and operated some runners on its own account and made sure they loaded vital war goods. By 1864, Lee's soldiers were eating imported meat. Not wanting to draw Britain into a possible war with the Union, the Union Navy decided to apply the principles of international law in the conflict; captured British sailors were released, while Confederates went to prison camps. The ships were unarmed (the weight of the cannon would slow them down), so they posed no danger to the Navy warships. Therefore, blockade running was reasonably safe for both sides.

One example of the lucrative (and short-lived) nature of the blockade running trade was the ship Banshee, which operated out of Nassau and Bermuda. She was captured on her seventh run into Wilmington, North Carolina, and confiscated by the U.S. Navy for use as a blockading ship. However, at the time of her capture, she had turned a 700% profit for her English owners, who quickly commissioned and built Banshee No. 2, which soon joined the firm's fleet of blockade runners.[22]

In May 1865, CSS Lark became the last Confederate ship to slip out of a Southern port and successfully evade the Union blockade when she left Galveston, Texas, for Havana.[23]

Throughout the conflict, at least 600,000 arms (mostly British Pattern 1853 Enfield rifles)[1] were smuggled by blockade runners to the Confederacy, 330,000 of them into the Gulf ports.[2] Such shipments were enough to prolong the war by two years and kill 400,000 additional Americans.[3][4][5]

Impact on the Confederacy

The Union blockade was a powerful weapon that eventually ruined the Southern economy, at the cost of very few lives.[24] The measure of the blockade's success was not the few ships that slipped through, but the thousands that never tried it. Ordinary freighters had no reasonable hope of evading the blockade and stopped calling at Southern ports. The interdiction of coastal traffic meant that long-distance travel now depended on the rickety railroad system, which never overcame the devastating impact of the blockade. Throughout the war, the South produced enough food for civilians and soldiers, but it had growing difficulty in moving surpluses to areas of scarcity and famine. Lee's army, at the end of the supply line, nearly always was short of supplies as the war progressed into its final two years.

When the blockade began in 1861, it was only partially effective. It has been estimated that only one in ten ships trying to evade the blockade were intercepted. However, the Union Navy gradually increased in size throughout the war, and was able to drastically reduce shipments into Confederate ports. By 1864, one in every three ships attempting to run the blockade were being intercepted.[25] In the final two years of the war, the only ships with a reasonable chance of evading the blockade were blockade runners specifically designed for speed.[26][27] Overall, the Union Navy wrecked or captured an estimated 1500 ships that attempted to run the blockade. During the four years of the blockade, Southern ports saw approximately 8000 trips. By contrast, over 20,000 took place during the four years preceding the war.[28]

The blockade almost totally choked off Southern cotton exports, which the Confederacy depended on for hard currency. Cotton exports fell 95%, from 10 million bales in the three years prior to the war to just 500,000 bales during the blockade period.[18] The blockade also largely reduced imports of food, medicine, war materials, manufactured goods, and luxury items, resulting in severe shortages and inflation. Shortages of bread led to occasional bread riots in Richmond and other cities, showing that patriotism was not sufficient to satisfy the daily demands of the people. Land routes remained open for cattle drovers, but after the Union seized control of the Mississippi River in summer 1863, it became impossible to ship horses, cattle and swine from Texas and Arkansas to the eastern Confederacy. The blockade was a triumph of the Union Navy and a major factor in winning the war.

Another consequence, perhaps not intended but highly significant, was the crippling of the interstate slave trade; any shipping route, navigable inland waterway, or railroad that had been used to transport cotton was also used to move "negroes" around the country. The blockade both prevented the South from efficiently deploying its foundational labor force and disrupted free flow of one of the key sources of cash and collateral in the Confederate economy.[29] For example, the autobiography of H. C. Bruce recalled the collapse of the business of Negro-Trader White, who had spent the better part of 30 years profiting from chattel arbitrage : "From 1862 to the close of the war, slave property in the state of Missouri was almost a dead weight to the owner; he could not sell because there were no buyers. The business of the Negro trader was at an end, due to the want of a market. He could not get through the Union lines South with his property, that being his market."[30]

A significant secondary impact of the naval blockade was a resulting scarcity of salt throughout the South. In Antebellum times, returning cotton-shipping ships were often ballasted with salt, which was bountifully produced at a prehistoric dry lake near Syracuse, New York, but which had never been produced in significant quantity in the Southern States. Salt was necessary for curing meat; its lack led to significant hardship in keeping the Confederate forces fed as well as severely impacting the populace. In addition to blocking salt from being imported into the Confederacy, Union forces actively destroyed attempts to build salt-producing facilities at Avery Island, Louisiana (destroyed in 1863 by Union forces under General Nathaniel P. Banks), outside the bay at Port St. Joe, Florida (destroyed in 1862 by the Union ship Kingfisher), at Darien, Georgia, at Saltville, Virginia (captured by Union forces in December 1864), and various sites hidden in marshes and bayous.[31]

Impact For the Union Bail

The southern cotton industry began to heavily influence the British economy. Cotton was a highly profitable cash crop, known in the 19th century as "white gold".[32] On the eve of the war, 1,390,938,752 pounds weight of cotton were imported into Great Britain in 1860. Of this, the United States supplied 1,115,890,608 pounds, or about five-sixths of the whole.[33] Not only was Great Britain aware of the impact of Southern cotton, but so was the South. They were confident that their industry held large power, so much, that they referred to their industry as "King Cotton." This slogan was used to declare its supremacy in America. On the floor of the U.S. Senate, Senator James Henry Hammond declaimed (March 4, 1858): "You dare not make war upon cotton! No power on earth dares make war upon it. Cotton is king."[34] The South proclaimed that many domestic and even some international markets depended so heavily on their cotton, that no one would dare spark tensions with the South. They also viewed this slogan as their reasoning behind why they should achieve their efforts in seceding from the Union. The Southern Cotton industry was so confident in the power of cotton diplomacy, that without warning, they refused to export cotton for one day.

Imagining an overwhelming response of pleas for their cotton, the Southern cotton industry experienced quite the opposite. With the decisions of Lincoln and the lack of intervention on Great Britain's part, the South was officially blockaded. Following the U.S. announcement of its intention to establish an official blockade of Confederate ports, foreign governments began to recognize the Confederacy as a belligerent in the Civil War.[35] Great Britain declared belligerent status on May 13, 1861, followed by Spain on June 17 and Brazil on August 1. This was the first glimpse of failure for the Confederate South.

The decision to blockade Southern port cities took a large toll on the British economy but they weighed their consequences. Great Britain had a good amount of cotton stored up in warehouses in several locations that would provide for their textile needs for some time. But eventually Great Britain began to see the effects of the blockade, "the blockade had a negative impact on the economies of other countries. Textile manufacturing areas in Britain and France that depended on Southern cotton entered periods of high unemployment..." in the so-called Lancashire Cotton Famine.[35] Nearly 80% of the cotton used in the British textile mills came from the South, and the scarcity of cotton caused by the blockade caused the price of cotton to rapidly rise by 150% by the summer of 1861.[32] The article written in the New York Times further proves that Great Britain was aware of the influence of cotton in their empire, "Nearly one million of operatives are employed in the manufacture of cotton in Great Britain, upon whom, at least five or six millions more depend for their daily subsistence. It is no exaggeration to say, that one-quarter of the inhabitants of England are directly dependent upon the supply of cotton for their living."[36] Despite these consequences, Great Britain concluded that their decision was crucial in terms of reaching abolition of slavery in the United States.

The blockade led to Egypt replacing the South as Britain's principal source of cotton.[32] Likewise, Egyptian cotton replaced American cotton as the principal source of cotton for the textile mills of France and the Austrian empire not only for the civil war, but for the rest of the 19th century.[32] In 1861, only 600,000 cantars (one cantar being the equivalent of 100 pounds) of cotton were exported from Egypt; by 1863 Egypt had exported 1.3 million cantars of cotton.[32] Nearly 93% of the tax revenue collected by the Egyptian state came from taxing cotton while every landowner in the Nile river valley had started to grow cotton.[32] The vast majority of the land in the Nile river valley were owned by a clique of wealthy families of Turkish, Albanian and Circassian origin, known in Egypt as the Turco-Circassian elite and to foreigners as the pasha class as most of the landowners usually had the Ottoman title of pasha (the equivalent of a title of nobility). The fellaheen (peasantry) became the subject of a ruthless system of exploitation as the landowners pressed the fellaheen to grow cotton instead of food, settling a bout of inflation caused by the shortage of food as more and more land was devoted to growing cotton.[32] The wealth created by the cotton boom caused by the Union blockade led to the redevelopment of much of Cairo and Alexandria as much of the medieval cores of both cities were razed to make way for modern buildings.[32] The cotton boom attracted a significant number of foreign businessmen to Egypt, of which the largest number were Greeks.[32] The wealth created by the cotton boom in Egypt was ended by the end of the blockade in 1865, which allowed the cotton from the South to ultimately reenter the world market, helping to lead to Egypt's bankruptcy in 1876.[32]

Confederate response

The Confederacy constructed torpedo boats, tending to be small, fast steam launches equipped with spar torpedoes, to attack the blockading fleet. Some torpedo boats were refitted steam launches; others, such as the CSS David class, were purpose-built. The torpedo boats tried to attack under cover of night by ramming the spar torpedo into the hull of the blockading ship, then backing off and detonating the explosive. The torpedo boats were not very effective and were easily countered by simple measures such as hanging chains over the sides of ships to foul the screws of the torpedo boats, or encircling the ships with wooden booms to trap the torpedoes at a distance.

One historically notable naval action was the attack of the Confederate submarine H. L. Hunley, a hand-powered submarine launched from Charleston, South Carolina, against Union blockade ships. On the night of 17 February 1864, Hunley attacked Housatonic. Housatonic sank with the loss of five crew; Hunley also sank, taking her crew of eight to the bottom.

Major engagements

The first victory for the U.S. Navy during the early phases of the blockade occurred on 24 April 1861, when the sloop Cumberland and a small flotilla of support ships began seizing Confederate ships and privateers in the vicinity of Fort Monroe off the Virginia coastline. Within the next two weeks, Flag Officer Garrett J. Pendergrast had captured 16 enemy vessels, serving early notice to the Confederate War Department that the blockade would be effective if extended.[37]

Early battles in support of the blockade included the Blockade of the Chesapeake Bay,[38] from May to June 1861, and the Blockade of the Carolina Coast, August–December 1861.[39] Both enabled the Union Navy to gradually extend its blockade southward along the Atlantic seaboard.

In early March 1862, the blockade of the James River in Virginia was gravely threatened by the first ironclad, CSS Virginia in the dramatic Battle of Hampton Roads. Only the timely entry of the new Union ironclad Monitor forestalled the threat. Two months later, Virginia and other ships of the James River Squadron were scuttled in response to the Union Army and Navy advances.

The port of Savannah, Georgia, was effectively sealed by the reduction and surrender of Fort Pulaski on 11 April.[40]

The largest Confederate port, New Orleans, Louisiana, was ill-suited to blockade running since the channels could be sealed by the U.S. Navy. From 16 to 22 April, the major forts below the city, Forts Jackson and St. Philip were bombarded by David Dixon Porter's mortar schooners. On 22 April, Flag Officer David Farragut's fleet cleared a passage through the obstructions. The fleet successfully ran past the forts on the morning of 24 April. This forced the surrender of the forts and New Orleans.[41]

The Battle of Mobile Bay on 5 August 1864 closed the last major Confederate port in the Gulf of Mexico.

In December 1864, Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles sent a force against Fort Fisher, which protected the Confederacy's access to the Atlantic from Wilmington, North Carolina, the last open Confederate port on the Atlantic Coast.[42] The first attack failed, but with a change in tactics (and Union generals), the fort fell in January 1865, closing the last major Confederate port.

As the Union fleet grew in size, speed and sophistication, more ports came under Federal control. After 1862, only three ports east of the Mississippi—Wilmington, North Carolina; Charleston, South Carolina; and Mobile, Alabama—remained open for the 75–100 blockade runners in business. Charleston was shut down by Admiral John A. Dahlgren's South Atlantic Blockading Squadron in 1863. Mobile Bay was captured in August 1864 by Admiral David Farragut. Blockade runners faced an increasing risk of capture—in 1861 and 1862, one sortie in 9 ended in capture; in 1863 and 1864, one in three. By war's end, imports had been choked to a trickle as the number of captures came to 50% of the sorties. Some 1,100 blockade runners were captured (and another 300 destroyed). British investors frequently made the mistake of reinvesting their profits in the trade; when the war ended they were stuck with useless ships and rapidly depreciating cotton. In the final accounting, perhaps half the investors took a profit, and half a loss.

The Union victory at Vicksburg, Mississippi, in July 1863 opened up the Mississippi River and effectively cut off the western Confederacy as a source of troops and supplies. The fall of Fort Fisher and the city of Wilmington, North Carolina, early in 1865 closed the last major port for blockade runners, and in quick succession Richmond was evacuated, the Army of Northern Virginia disintegrated, and General Lee surrendered. Thus, most economists give the Union blockade a prominent role in the outcome of the war. (Elekund, 2004)

Squadrons

The Union naval ships enforcing the blockade were divided into squadrons based on their area of operation.[43]

Atlantic Blockading Squadron

The Atlantic Blockading Squadron was a unit of the United States Navy created in the early days of the American Civil War to enforce a blockade of the ports of the Confederate States. It was originally formed in 1861 as the Coast Blockading Squadron before being renamed May 17, 1861. It was split the same year for the creation of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron and the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron.

North Atlantic Blockading Squadron

The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron was based at Hampton Roads, Virginia, and was tasked with coverage of Virginia and North Carolina. Its official range of operation was from the Potomac River to Cape Fear in North Carolina. It was tasked primarily with preventing Confederate ships from supplying troops and with supporting Union troops. It was created when the Atlantic Blockading Squadron was split between the North and South Atlantic Blockading Squadrons on 29 October 1861. After the end of the war, the squadron was merged into the Atlantic Squadron on 25 July 1865.[43]

Commanders

| Squadron Commander | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough | 18 September 1861[44] | 4 September 1862 |

| Acting Rear Admiral[44] Samuel Phillips Lee | 5 September 1862[44] | 11 October 1864 |

| Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter | 12 October 1864 | 27 April 1865 |

| Acting Rear Admiral[44] William Radford | 28 April 1865[44] | 25 July 1865 |

South Atlantic Blockading Squadron

The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron was tasked primarily with preventing Confederate ships from supplying troops and with supporting Union troops operating between Cape Henry in Virginia down to Key West in Florida. It was created when the Atlantic Blockading Squadron was split between the North and South Atlantic Blockading Squadrons on 29 October 1861. After the end of the war, the squadron was merged into the Atlantic Squadron on 25 July 1865.

Commanders

| Squadron Commander | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont | 18 September 1861[44] | 5 July 1863 |

| Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren | 6 July 1863[44] | 25 July 1865 |

Gulf Blockading Squadron

The Gulf Blockading Squadron was a squadron of the United States Navy in the early part of the War, patrolling from Key West to the Mexican border. The squadron was the largest in operation. It was split into the East and West Gulf Blockading Squadrons in early 1862 for more efficiency.

Commanders

| Squadron Commander | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Flag Officer William Mervine | 6 May 1861 | 21 September 1861 |

| Flag Officer William McKean | 22 September 1861 | 20 January 1862 |

East Gulf Blockading Squadron

The East Gulf Blockading Squadron, assigned the Florida coast from east of Pensacola to Cape Canaveral, was a minor command.[45] The squadron was headquartered in Key West and was supported by a U.S. Navy coal depot and storehouse built during 1856–1861.[46]

Commanders

| Squadron Commander[47] | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Flag Officer William McKean | 20 January 1862 | 3 June 1862 |

| Flag Officer James L. Lardner | 4 June 1862 | 8 December 1862 |

| Acting Rear Admiral Theodorus Bailey | 9 December 1862 | 6 August 1864 |

| Captain Theodore P. Greene (commander pro tem) |

7 August 1864 | 11 October 1864 |

| Acting Rear Admiral Cornelius Stribling | 12 October 1864 | 12 June 1865 |

West Gulf Blockading Squadron

The West Gulf Blockading Squadron was tasked primarily with preventing Confederate ships from supplying troops and with supporting Union troops along the western half of the Gulf Coast, from the mouth of the Mississippi to the Rio Grande and south, beyond the border with Mexico. It was created early in 1862 when the Gulf Blockading Squadron was split between the East and West. This unit was the main military force deployed by the Union in the capture and brief occupation of Galveston, Texas in 1862.

Commanders

| Squadron Commander[47] | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Rear Admiral David Farragut | 20 January 1862 | 29 November 1864 |

| Commodore James S. Palmer | 30 November 1864 | 22 February 1865 |

| Acting Rear Admiral Henry K. Thatcher | 23 February 1865 | 12 June 1865 |

Retrospective consideration

After the war, former Confederate Navy officer and Lost Cause proponent Raphael Semmes contended that the announcement of a blockade had carried de facto recognition of the Confederate States of America as an independent national entity since countries do not blockade their own ports but rather close them (See Boston Port Act).[48] Under international law and maritime law, however, nations had the right to stop and search neutral ships in international waters if they were suspected of violating a blockade, something port closures would not allow. In an effort to avoid conflict between the United States and Britain over the searching of British merchant vessels thought to be trading with the Confederacy, the Union needed the privileges of international law that came with the declaration of a blockade.

However Semmes contends that by effectively declaring the Confederate States of America to be belligerents—rather than insurrectionists, who under international law were not eligible for recognition by foreign powers—Lincoln opened the way for Britain and France to potentially recognize the Confederacy. Britain's proclamation of neutrality was consistent with the Lincoln Administration's position—that under international law the Confederates were belligerents—and helped legitimize the Confederate States of America's national right to obtain loans and buy arms from neutral nations. The British proclamation also formally gave Britain the diplomatic right to discuss openly which side, if either, to support.[18]

See also

- Bibliography of American Civil War naval history

- Postage stamps and postal history of the Confederate States § Blockade mail

References

- ^ a b Kevin Dougherty (30 September 2010). Weapons of Mississippi. University Press of Mississippi. p. 87. ISBN 9-7816-0473-4522.

- ^ a b Daniel O'flaherty (August 1955). "The Blockade That Failed". American Heritage. Vol. 6, no. 5.

- ^ a b "Alabama Claims, 1862-1872". GlobalSecurity.org.

- ^ a b David Keys (24 June 2014). "Historians reveal secrets of UK gun-running which lengthened the American civil war by two years". The Independent.

- ^ a b Paul Hendren (April 1933). "The Confederate Blockade Runners". United States Naval Institute.

- ^ "History Place". History Place. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ Time-Life, p. 29.

- ^ Time-Life, p. 31.

- ^ "National Park Service". nps.gov. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ U.S Naval Blockade

- ^ Soley, James Russel, The Blockade and the Cruisers

- ^ Davis, Kenneth C. Don't Know Much About The Civil War. ISBN 0688118143

- ^ "Blockade essays" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events of the year: 1862. New York: D. Appleton & Company. 1863. p. 604.

- ^ "U.S. Navy, Maritime History of Massachusetts--A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary". nps.gov. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ Time-Life, p. 33.

- ^ Barrett, John G. (1995). The Civil War in North Carolina. ISBN 978-0-8078-4520-2. Retrieved 8 June 2010 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d "Lincoln biography". Americanpresident.org. Archived from the original on 13 October 2006. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ Wyllie, 2007 p. 184

- ^ a b Porter 1981, p. 134.

- ^ "The Civil War On The Fringe: Blockade Runners". Something about Everything Military: America At War: The Civil War. Archived from the original on 5 January 2011.

- ^ Time-Life, p. 95.

- ^ "Galveston Weekly News, April 26, 1865". Nautarch.tamu.edu. 3 July 2000. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ Saxe, David Warren (2006). Land and Liberty I: A Chronology of ... ISBN 978-1-59942-405-7. Retrieved 8 June 2010 – via Google Books.

- ^ "American Civil War: The Blockade and the War at Sea". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ Bulloch, James Dunwody (1884). The secret service of the Confederate States in Europe, or, How the Confederate cruisers were equipped. G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York. p. 460.

- ^ Merli, Frank J. (1970). Great Britain and the Confederate Navy, 1861–1865. Indiana University Press, Indiana. p. 342. ISBN 0-253-21735-0.

- ^ McPherson, James M. (1999). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 378–382. ISBN 978-0-19-516895-2.

- ^ Johnson, Walter (2013). River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 86. ISBN 9780674074880. LCCN 2012030065. OCLC 827947225. OL 26179618M.

- ^ "Henry Clay Bruce, 1836-1902. The New Man. Twenty-Nine Years a Slave. Twenty-Nine Years a Free Man". docsouth.unc.edu. pp. 102–103. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Anne Ewbank (28 September 2018). "How Salt Helped Win the Civil War". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Schwartzstein, Peter (1 August 2016). "How the American Civil War Built Egypt's Vaunted Cotton Industry and Changed the Country Forever The battle between the U.S. and the Confederacy affected global trade in astonishing ways". The Smithsonian. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "England and the Cotton Supply". The New York Times. June 1861. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Underwood, Rodman L. (18 March 2008). Waters of Discord: The Union Blockade of Texas During the Civil War. McFarland. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-7864-3776-4.

- ^ a b "Milestones: 1861–1865". U.S. Department of State. Office of the Historian. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ "England and the Cotton Supplu". The New York Times. 1 June 1861. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Time-Life, page 24.

- ^ "National Park Service". nps.gov. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ "National Park Service". nps.gov. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ NPS.gov, National Park Service Summary Siege of Fort Pulaski

- ^ NPS.gov, National Park Service Summary Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philips

- ^ "Amphibious Warfare: Nineteenth Century". Exwar.org. Archived from the original on 2 October 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ a b Robert M Browning JR (1993). From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: the ... ISBN 978-0-8173-0679-3. Retrieved 8 June 2010 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g Civil War Desk Reference, p. 550.

- ^ Anderson, 1989 p. 118

- ^ Diane Greer and Mary Evans (20 March 1972). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: U. S. Coast Guard Headquarters, Keywest Station / U. S. Navy Coal Depot and Storehouse; also, Building #1". National Park Service. Retrieved 5 April 2017. With two photos from 1972.

- ^ a b Civil War Desk Reference, p. 551.

- ^ "Jenkins essay". Wideopenwest.com. Archived from the original on 26 May 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Bern (1989). By Sea and by River The Naval History of the Civil. Da Capo Press, New York. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-615-17222-4. Url

- Browning, Robert M. Jr. (1993). From Cape Charles to Cape Fear. The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. University of Alabama Press. p. 472. Url

- —— (2002). Success is All That Was Expected. The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. Washington DC: Brassley's. p. 432. ISBN 978-1-57488-514-9. Url

- ——— (2015). Lincoln's Trident: The West Gulf Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. University of Alabama Press. p. 700.

- Buker, George E. (1993). Blockaders, Refugees, and Contrabands: Civil War on Florida's Gulf Coast, 1861–1865. University of Alabama Press. p. 235. Url

- Coker, P. C. III (1987). Charleston's Maritime Heritage, 1670–1865: An Illustrated History. CokerCraft Press. p. 314. Url

- Elekund, R.B.; Jackson, M.; J.D., Thornton (2004). The 'Unintended Consequences' of Confederate Trade Legislation. Eastern Economic Journal. p. 123.

- Fowler, William M. (1990). Under Two Flags: The American Navy in the Civil War. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-393-02859-1.

- Greene, Jack (1998). Ironclads at War; Combined Publishing

- McPherson, James M., War on the Waters: The Union & Confederate Navies, 1861-1865 University of North Carolina Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-8078-3588-3

- Porter, E.B. (1981). Sea Power: A Naval History. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-607-4.

- Surdam, David G. (2001). Northern Naval Superiority and the Economics of the American Civil War; University of South Carolina Press

- Time-Life Books (1983) The Blockade: Runners and Raiders. The Civil War series; Time-Life Books, ISBN 0-8094-4708-8.

- Vandiver, Frank Everson (1947). Confederate Blockade Running Through Bermuda, 1861–1865: Letters And Cargo Manifests, primary documents

- Wagner, Margaret E., Gallagher, Gary W. and Finkelman, Paul ed., (2002) The Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference

Simon & Schuster, New York. ISBN 978-1-4391-4884-6 - Wise, Stephen R. (1991). Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running During the Civil War.

Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 403. ISBN 978-0-87249-554-8. Url - Wyllie, Arthur (2007). The Confederate States Navy.

Lulu.com. p. 466. ISBN 978-0-615-17222-4.[self-published source?] Url1 Url2 - Wynne, Nick & Cranshaw, Joe (2011). Florida Civil War Blockades

History Press, Charleston, SC, ISBN 978-1-60949-340-0.

Further reading

- Calore, Paul (2002). Naval Campaigns of the Civil War. McFarland. p. 232. Url

- Tucker, Spencer (2010). The Civil War Naval Encyclopedia, Volume 1.

ABC-CLIO. p. 829. ISBN 978-1-59884-338-5. Url

External links

- National Park Service listing of campaigns

- Book review: Lifeline of the Confederacy

- Unintended Consequences of Confederate Trade Legislation

- The Hapless Anaconda: Union Blockade 1861–1865

- Sabine Pass and Galveston Were Successful Blockade-Running Ports By W. T. Block

- Civil War Blockade Organization

- David G. Surdam, Northern Naval Superiority and the Economics of the American Civil War ISBN 1-57003-407-9

- "The Egotistigraphy", by John Sanford Barnes. An autobiography, including his Civil War Union Navy service on a ship participating in the blockade, USS Wabash, privately printed 1910. Internet edition edited by Susan Bainbridge Hay 2012