Contents

पाटलिपुत्र (talk | contribs) →Contemporary works: ewer |

पाटलिपुत्र (talk | contribs) →Rise to power: Book of songs |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

==Rise to power== |

==Rise to power== |

||

| ⚫ | Lu'lu' was an [[Armenians|Armenian]] convert to [[Islam]],<ref>Islamic art and architecture 650-1250 By Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar, Marilyn Jenkins, pg, 134</ref> and a freed slave in the household of the Zangid ruler [[Nur al-Din Arslanshah I|Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I]].<ref>{{cite book |title=Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs - MetPublications - The Metropolitan Museum of Art |date=2016 |publisher=Metropolitan Museum of Art |page=61 |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Court_and_Cosmos |language=en}}</ref> Recognized for his abilities as an administrator, he rose to the rank of [[atabeg]] and, after 1211, was appointed as atabeg for the successive child-rulers of Mosul, [[Nur ad-Din Arslan Shah II|Nur al-Din Arslan Shah II]] and his younger brother, [[Nasir ad-Din Mahmud|Nasir al-Din Mahmud]]. Both rulers were grandsons of [[Gökböri]], Emir of [[Erbil]], and this probably accounts for the animosity between him and Lu'lu'. In 1226 Gökböri, in alliance with [[Al-Mu'azzam Isa|al-Muazzam]] of Damascus, attacked Mosul. As a result of this military pressure, Lu'lu' was forced to make a submission to al-Muazzam. Nasir al-Din Mahmud was the last Zengid ruler of Mosul, he disappears from the records soon after Gökböri's death. He was killed by Lu'lu', by strangulation or starvation, and his killer then formally began to rule in Mosul in his own right.<ref>Gibb, pp. 700-701</ref><ref>Patton, pp.152-155</ref> |

||

Lu'lu' was an [[Armenians|Armenian]] convert to [[Islam]],<ref>Islamic art and architecture 650-1250 By Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar, Marilyn Jenkins |

|||

| ⚫ | , pg, 134</ref> and a freed slave in the household of the Zangid ruler [[Nur al-Din Arslanshah I|Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I]].<ref>{{cite book |title=Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs - MetPublications - The Metropolitan Museum of Art |date=2016 |publisher=Metropolitan Museum of Art |page=61 |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Court_and_Cosmos |language=en}}</ref> Recognized for his abilities as an administrator, he rose to the rank of [[atabeg]] and, after 1211, was appointed as atabeg for the successive child-rulers of Mosul, [[Nur ad-Din Arslan Shah II|Nur al-Din Arslan Shah II]] and his younger brother, [[Nasir ad-Din Mahmud|Nasir al-Din Mahmud]]. Both rulers were grandsons of [[Gökböri]], Emir of [[Erbil]], and this probably accounts for the animosity between him and Lu'lu'. In 1226 Gökböri, in alliance with [[Al-Mu'azzam Isa|al-Muazzam]] of Damascus, attacked Mosul. As a result of this military pressure, Lu'lu' was forced to make a submission to al-Muazzam. Nasir al-Din Mahmud was the last Zengid ruler of Mosul, he disappears from the records soon after Gökböri's death. He was killed by Lu'lu', by strangulation or starvation, and his killer then formally began to rule in Mosul in his own right.<ref>Gibb, pp. 700-701</ref><ref>Patton, pp.152-155</ref> |

||

===The Book of Songs (1218-1219)=== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

During this period, Lu'lu' appears prominently in the 1218-1219 edition the ''[[Kitāb al-aghānī]]'' ("Book of Songs"), probably made in [[Mosul]]. The whole edition consists in 20 volumes, four of them now being in the National Library in Cairo (II, IV, XI, XIII), and two more in the Feyzullah Libray, Istanbul (XVII, XIX), and had several miniatures, only six of which have remained.<ref name="DSR">{{cite journal |last1=Rice |first1=D. S. |title=The Aghānī Miniatures and Religious Painting in Islam |journal=The Burlington Magazine |date=1953 |volume=95 |issue=601 |pages=128–135 |url=http://warfare.tk/Turk/The_Aghani_Miniatures_and_Religious_Painting_in_Islam-D_S_Rice.htm |issn=0007-6287}}</ref> |

|||

<gallery widths="150px" heights="200px" perrow="5"> |

|||

File:Kitāb al-aghānī (“The Book of Songs”) by Abū al-Faraj al-Iṣbahānī.jpg|Lu'lu' with musicians and attendants. ''[[Kitāb al-aghānī]]'', Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol IV. Cairo, Egyptian National Library, Ms Farsi 579.<ref name="DSR"/> |

|||

File:Kitab al-Aghani, 13th century, Volume XI miniature.jpg|Lu'lu' with two senior figures, possibly a turbaned Christian bishop and a Turkish military leader with a fur-trimmed hat. ''Kitāb al-aghānī'', Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XI. Cairo, Egyptian National Library, Ms Farsi 579.<ref name="DSR"/> |

|||

File:Badr al-Din Lu'lu'.jpg|Lu'lu' as enthroned atabeg with attendants. ''Kitāb al-aghānī'', Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XVII. Istanbul, Millet Library, Ms Feyzullah Efendi 1566.<ref name="DSR"/> |

|||

File:Kitab al-Aghani, 1219, Volume XIX miniature.jpg|Lu'lu' on horse with attendants. ''Kitāb al-aghānī'', Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XIX. Istanbul, Millet Library, Ms Feyzullah Efendi 1565.<ref name="DSR"/> |

|||

| ⚫ | File:Equestrian Portrait of Badr al-Din Lu'lu from Kitab al-Aghani (Book of Songs) of Abu-l-Farraj al-Isfahani, Mosul 1217-19, David Collection.jpg|Badr al-Din Lu'lu on horse. ''Kitāb al-aghānī'', Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XX. David Collection, Copenhagen, Denmark.<ref>{{cite book |title=Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs - MetPublications - The Metropolitan Museum of Art |date=2016 |publisher=Metropolitan Museum of Art |page=61 |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Court_and_Cosmos |language=en}}</ref> |

||

</gallery> |

|||

==Ruler of Mosul== |

==Ruler of Mosul== |

||

Revision as of 16:43, 13 January 2024

Badr al-Din Lu'lu' (Arabic: بَدْر الدِّين لُؤْلُؤ) (died 1259) (the name Lu'Lu' means 'The Pearl', indicative of his servile origins) was successor to the Zengid emirs of Mosul, where he governed in variety of capacities from 1234 to 1259 following the death of Nasir ad-Din Mahmud. Originally a slave of the Zengid ruler Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I, he was the first Middle-Eastern mamluk to transcend servitude and become an emir in his own right, founding the dynasty of the Lu'lu'id emirs (1234-1262), and anticipating the rise of the Bahri Mamluks of the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt by twenty years (but postdating the rise of the Mamluk dynasty in India). He preserved control of al-Jazira through a series of tactical submissions to larger neighboring powers, at various times recognizing Ayyubid, Rûmi Seljuq, and Mongol overlords. His surrender to the Mongols temporarily spared Mosul the destruction experienced by other settlements in Mesopotamia.

Rise to power

Lu'lu' was an Armenian convert to Islam,[2] and a freed slave in the household of the Zangid ruler Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I.[3] Recognized for his abilities as an administrator, he rose to the rank of atabeg and, after 1211, was appointed as atabeg for the successive child-rulers of Mosul, Nur al-Din Arslan Shah II and his younger brother, Nasir al-Din Mahmud. Both rulers were grandsons of Gökböri, Emir of Erbil, and this probably accounts for the animosity between him and Lu'lu'. In 1226 Gökböri, in alliance with al-Muazzam of Damascus, attacked Mosul. As a result of this military pressure, Lu'lu' was forced to make a submission to al-Muazzam. Nasir al-Din Mahmud was the last Zengid ruler of Mosul, he disappears from the records soon after Gökböri's death. He was killed by Lu'lu', by strangulation or starvation, and his killer then formally began to rule in Mosul in his own right.[4][5]

The Book of Songs (1218-1219)

During this period, Lu'lu' appears prominently in the 1218-1219 edition the Kitāb al-aghānī ("Book of Songs"), probably made in Mosul. The whole edition consists in 20 volumes, four of them now being in the National Library in Cairo (II, IV, XI, XIII), and two more in the Feyzullah Libray, Istanbul (XVII, XIX), and had several miniatures, only six of which have remained.[6]

-

Lu'lu' with musicians and attendants. Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol IV. Cairo, Egyptian National Library, Ms Farsi 579.[6]

-

Lu'lu' with two senior figures, possibly a turbaned Christian bishop and a Turkish military leader with a fur-trimmed hat. Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XI. Cairo, Egyptian National Library, Ms Farsi 579.[6]

-

Lu'lu' as enthroned atabeg with attendants. Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XVII. Istanbul, Millet Library, Ms Feyzullah Efendi 1566.[6]

-

Lu'lu' on horse with attendants. Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XIX. Istanbul, Millet Library, Ms Feyzullah Efendi 1565.[6]

-

Badr al-Din Lu'lu on horse. Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XX. David Collection, Copenhagen, Denmark.[7]

Ruler of Mosul

In 1234 Lu'lu' minted the first coins in his own name. Following his usurpation his new position as ruler of Mosul was recognised by the Abbasid Khalif, Al-Mustansir, who bestowed upon him the praise name al-Malik al-Rahim (The Merciful King). During his reign he sided with successive Ayyubid rulers in his disputes with other local princes. In 1237 Lu'Lu' was defeated in battle by the former army of the Khwarazmshah and his camp was thoroughly looted. Lu'lu' was in conflict with Yezidi Kurds in his territories, he ordered the execution of one Yezidi leader, Hasan ibn Adi, and 200 of his followers in 1254.[8]

Lu'lu' built extensively in his domain, improving the fortifications of Mosul, the Sinjar Gate bearing his device survived into the 20th century, and constructing religious structures and caravanserais. He built the shrines of Imam Yahya (1239) and Awn al-Din (1248). The ruins of his palace complex, known as the Qara Saray (1233-1259), were visible until the 1980s.[9]

During the final stages of the Mongol invasion of Persia and Mesopotamia, in 1258, while about 80 years old, Badr al-Din went in person to Meraga to offer his submission to the Mongol invader Hulagu.[10] Badr al-Din helped the Khan in his following campaigns in Syria. Mosul was spared destruction, but Badr al-Din died shortly thereafter in 1259.[10] Badr al-Din's son Isma'il ibn Lu'lu' (1259-1262) continued in his father's steps, but after the Mongol defeat in the Battle of Ain Jalut (1260) against the Mamluks, he sided with the latter and revolted against the Mongols. Hulagu then besieged the city of Mosul for nine month, and utterly destroyed it in 1262.[10][11]

Family

- Isma'il ibn Lu'lu', the son of Badr al-Din Lu'lu, ruled Mosul for only three years (1259 - 1262) before his city was lost to the Mongols.[12]

- A daughter of Lu'lu' was set to marry Aybak, as his second wife after Shajar al-Durr. However, Aybak was killed before the marriage could take place.

Contemporary works

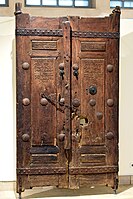

Mosul under Badr al-Din Lu'lu' was characterized by fine crafstmanship, particularly in the areas of woodworking and metalworking, with the production of some of the best inlaid metalworks of the period.[13]

-

Coin of Badr al Din Lu'lu', Mosul, 1210–1259. The central legend starts with "Lu'Lu'" at the top (Arabic: لُؤْلُؤ). British Museum

-

Wooden door of the Great Mosque of Amadiya (13th century); the inscription mentions sultan Badr-addin Ibn Lulu Ibn Abdullah, the happy sultan, and the merciful king.

-

Homberg ewer. Inlaid Brass with Christian Iconography. probably Mosul, dated 1242–43.[14]

-

Inlaid brass tray of Badr al-Din Lu'lu'. Mosul, 13th cen. V&A.[15]

-

Cylindrical lidded box with an Arabic inscription recording its manufacture for the ruler of Mosul, Badr al-Din Lu'lu

-

Ewer manufactured in Mosul, 1251-1275.[16]

References

- ^ Flood, Finbarr Barry (2017). A Turk in the Dukhang? Comparative Perspectives on Elite Dress in Medieval Ladakh and the Caucasus. Austrian Academy of Science Press. p. 231 & 246 Fig.10.

- ^ Islamic art and architecture 650-1250 By Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar, Marilyn Jenkins, pg, 134

- ^ Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs - MetPublications - The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2016. p. 61.

- ^ Gibb, pp. 700-701

- ^ Patton, pp.152-155

- ^ a b c d e Rice, D. S. (1953). "The Aghānī Miniatures and Religious Painting in Islam". The Burlington Magazine. 95 (601): 128–135. ISSN 0007-6287.

- ^ Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs - MetPublications - The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2016. p. 61.

- ^ Kreyenbroek and Rashow, p. 4

- ^ Bloom and Blair (eds.), p. 249

- ^ a b c Bretschneider, E. (5 November 2013). Mediaeval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources: Fragments Towards the Knowledge of the Geography and History of Central and Western Asia from the 13th to the 17th Century: Volume II. Routledge. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-136-38056-3.

- ^ Bloom and Blair (eds.), pp. 249, 499

- ^ Spengler and Sayles, p. 140

- ^ Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs - MetPublications - The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2016. p. 265 ff.

- ^ Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs - MetPublications - The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2016. p. 265.

- ^ Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs - MetPublications - The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2016. p. 62.

- ^ "Mosul ewer 1250-1275". recherche.smb.museum.

Bibliography

- Bloom, J.M. and Blair, S.S. (eds.) (2009) The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture, Volume I: Abarquh to Dawlat Qatar, Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Gibb, H.A.R. (1969) [1962]. "The Aiyubids". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Wolff, Robert Lee; Hazard, Harry W. (eds.). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Later Crusades, 1189–1311 (Second ed.). Madison, Milwaukee, and London: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 693–714. ISBN 0-299-04844-6.

- Kreyenbroek, P.G. and Rashow, K.J. (2005) God and Sheik Adi are Perfect, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden

- Patton, D. (1988) Ibn al-Sāʿi's Account of the Last of the Zangids, Zeitschrift der Deutschen, Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 138, No. 1, pp. 148–158, Harrassowitz Verlag Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43377738 [1]

- Spengler, W.F. and Sayles, W.G. (1992) Turkoman Figural Bronze Coins and Their Iconography: The Artuquids, Clio's Cabinet, Lodi

External links

- Imam Awn al-Din Mashhad (Mosul) [2] Archived 2008-05-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Imam Yahya ibn al-Qasim Mashhad (Mosul) [3] Archived 2011-05-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Sittna Zaynab Mausoleum (Sinjar) [4] Archived 2010-12-14 at the Wayback Machine

![Lu'lu' with musicians and attendants. Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol IV. Cairo, Egyptian National Library, Ms Farsi 579.[6]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3a/Kit%C4%81b_al-agh%C4%81n%C4%AB_%28%E2%80%9CThe_Book_of_Songs%E2%80%9D%29_by_Ab%C5%AB_al-Faraj_al-I%E1%B9%A3bah%C4%81n%C4%AB.jpg/125px-Kit%C4%81b_al-agh%C4%81n%C4%AB_%28%E2%80%9CThe_Book_of_Songs%E2%80%9D%29_by_Ab%C5%AB_al-Faraj_al-I%E1%B9%A3bah%C4%81n%C4%AB.jpg)

![Lu'lu' with two senior figures, possibly a turbaned Christian bishop and a Turkish military leader with a fur-trimmed hat. Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XI. Cairo, Egyptian National Library, Ms Farsi 579.[6]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e7/Kitab_al-Aghani%2C_13th_century%2C_Volume_XI_miniature.jpg/134px-Kitab_al-Aghani%2C_13th_century%2C_Volume_XI_miniature.jpg)

![Lu'lu' as enthroned atabeg with attendants. Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XVII. Istanbul, Millet Library, Ms Feyzullah Efendi 1566.[6]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9b/Badr_al-Din_Lu%27lu%27.jpg/150px-Badr_al-Din_Lu%27lu%27.jpg)

![Lu'lu' on horse with attendants. Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XIX. Istanbul, Millet Library, Ms Feyzullah Efendi 1565.[6]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1f/Kitab_al-Aghani%2C_1219%2C_Volume_XIX_miniature.jpg/150px-Kitab_al-Aghani%2C_1219%2C_Volume_XIX_miniature.jpg)

![Badr al-Din Lu'lu on horse. Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XX. David Collection, Copenhagen, Denmark.[7]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1d/Equestrian_Portrait_of_Badr_al-Din_Lu%27lu_from_Kitab_al-Aghani_%28Book_of_Songs%29_of_Abu-l-Farraj_al-Isfahani%2C_Mosul_1217-19%2C_David_Collection.jpg/150px-Equestrian_Portrait_of_Badr_al-Din_Lu%27lu_from_Kitab_al-Aghani_%28Book_of_Songs%29_of_Abu-l-Farraj_al-Isfahani%2C_Mosul_1217-19%2C_David_Collection.jpg)

![Inlaid brass tray of Badr al-Din Lu'lu'. Mosul, 13th cen. V&A.[15]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/Inlaid_Brasses_of_Badr_al-Din_Lu%27lu%27_Tray%2C_Mosul%2C_13th_cen._V%26A.jpg/182px-Inlaid_Brasses_of_Badr_al-Din_Lu%27lu%27_Tray%2C_Mosul%2C_13th_cen._V%26A.jpg)

![Ewer manufactured in Mosul, 1251-1275.[16]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b9/Mosul_ewer%2C_1250-1275.jpg/147px-Mosul_ewer%2C_1250-1275.jpg)