Contents

Copper(II) phosphate are inorganic compounds with the formula Cu3(PO4)2. They can be regarded as the cupric salts of phosphoric acid. Anhydrous copper(II) phosphate and a trihydrate are blue solids.

Preparation

Hydrated copper(II) phosphate precipitates upon addition of a solution of alkali metal phosphate to an aqueous solution of copper(II) sulfate.[4] The anhydrous material can be produced by a high-temperature (1000 °C) reaction between diammonium phosphate and copper(II) oxide.[5]

- 2 (NH4)2HPO4 + 3 CuO → Cu3(PO4)2 + 3 H2O + 4 NH3

- In laboratories, copper phosphate is prepared by the addition of phosphoric acid to an alkali copper salt such as copper hydroxide, or basic copper carbonate.

- 3 Cu(OH)2 + 2 H3PO4 → 6 H2O + Cu3(PO4)2

- 3 Cu2(OH)2CO3 + 4 H3PO4 → 2 Cu3(PO4)2 + 3 CO2 + 9 H2O

Uses

Copper(II) phosphate has many uses. Due to it being a copper metal salt it can be used as a fungicide, it works by denaturating proteins and enzymes in cells of pathogens. Many other copper salts, such as copper sulfate, are used as fungicides. [6]

Another use of copper(II) phosphate is as a fertilizer. Copper is one of the 16 essential elements required for plant growth. Copper(II) phosphate supplies the plant with both phosphorus and copper, which stimulates growth.[7]

Structure

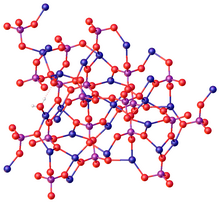

In terms of structure, copper(II) phosphates are coordination polymers, as is typical for most metal phosphates. The phosphate center is tetrahedral. In the anhydrous material, the copper centers are pentacoordinate. In the monohydrate, the copper adopts 6-, 5-, and 4-coordinate geometries.[8]

Minerals

It is relatively commonly encountered as the hydrated species Cu2(PO4)OH, which is green and occurs naturally as the mineral libethenite. Pseudomalachite, Cu5(PO4)2(OH)4, is the most common Cu phosphate in nature, typical for some oxidation zones of Cu ore deposits.[9][10]

References

- ^ S., Budavari (1996). The Merck Index - An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals (12th ed.). Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck and Co., Inc. p. 447. ISBN 9780911910124. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ John Rumble (June 18, 2018). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (99 ed.). CRC Press. pp. 5–188. ISBN 978-1138561632.

- ^ a b c NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0150". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Richardson, H. Wayne (2000). "Copper Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a07_567. ISBN 3527306730.

- ^ Shoemaker, G. L.; Anderson, J. B.; Kostiner, E. (15 September 1977). "Copper(II) phosphate". Acta Crystallographica Section B. 33 (9): 2969–2972. doi:10.1107/S0567740877010012.

- ^ "Copper Fungicides for Organic and Conventional Disease Management in Vegetables | Cornell Vegetables". www.vegetables.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2023-08-28.

- ^ Javadi, Morteza; Beuerlein, James E.; Arscott, Trevor G. (1991). "Effects of Phosphorus and Copper on Factors Influencing Nutrient Uptake, Photosynthesis, and Grain Yield of Wheat". ISSN 0030-0950.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Effenberger, H. (1985). "Cu3(PO4)2 · H2O: Synthese und Kristallstruktur". Journal of Solid State Chemistry. 57 (2): 240–247. Bibcode:1985JSSCh..57..240E. doi:10.1016/S0022-4596(85)80014-1.

- ^ [https://www.mindat.org/min-3299.html Pseudomalachite on Mindat

- ^ "List of Minerals". 21 March 2011.

External links

- Handbook of chemistry and physics http://www.hbcpnetbase.com/