Contents

Duguay-Trouin was an unprotected cruiser built for the French Navy in the 1870s, the only member of her class. She was ordered as part of a naval construction program after the Franco-Prussian War, and was intended to counter enemy commerce raiders; as such she had a high top speed of 15.5 knots (28.7 km/h; 17.8 mph), a heavy armament of five 194 mm (7.6 in) guns, and long cruising radius. Her design was based on the Duquesne-class cruisers, albeit reduced in size, and unlike the earlier vessels, she proved to be a reliable vessel in service.

The ship was sent to East Asia in 1884 to join the Far East Squadron under Amédée Courbet; she saw action later that year at the Battle of Fuzhou at the outset of the Sino-French War; there, she helped to sink three Chinese cruisers, and in company with the ironclad Triomphante, neutralized a series of Chinese coastal fortifications that blocked the French escape from Fuzhou. She next took part in the Keelung campaign on the island of Formosa, including the Battle of Tamsui in October 1884, but she missed the Battle of Shipu in February 1885 as she had run low on fuel. She fired the last French shots on Formosa on 3 April, shortly before the war ended.

Duguay-Trouin returned to France after the war, and was significantly modernized in the late 1880s. She briefly served in home waters before being sent abroad again in 1893. Over the rest of the 1890s, she alternated between the Pacific and Indochina stations, and she was sent to China again in 1898 in response to the Boxer Uprising. In 1899, she was struck from the naval register, renamed Vétéran, and converted into a depot ship to support a flotilla of torpedo boats defending French Indochina. She served in that capacity for a decade before being sold for scrap in 1911.

Design

In the late 1860s, the major European navies saw the success that Confederate commerce raiders had had during the American Civil War, and decided to respond with larger, faster cruisers that could catch such raiders. France's construction program was delayed by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871, but the navy quickly began preparations for the 1872 fiscal year.[1] Design work on first such vessels, the Duquesne class, began in 1871, and two were ordered in 1873 under the auspices of the naval construction program adopted in 1872. At the same time, the French naval minister Louis Pothuau issued a request on 14 September 1871 for smaller cruisers that could fulfill similar roles.[2]

The Conseil des Travaux (Council of Works) responded on 16 December with a set of specifications for the new cruiser. The number and caliber of main battery guns were reduced from seven to four and from 194 mm (7.6 in) to 164.7 mm (6.48 in), respectively, and the top speed would be 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph). Displacement was set at 2,532 metric tons (2,492 long tons; 2,791 short tons). Pothuau added a fifth gun to the forecastle and increased displacement to 2,880 t (2,830 long tons; 3,170 short tons) and forwarded the revised specifications to shipyards on 23 January 1872 to solicit detailed design proposals.[3]

Five naval designers responded to Pothuau's request, and on 13 August 1872, the Conseil evaluated the submissions. The design prepared by Romain Leopold Eynaud was selected; his design for the hull was based on the experimental aviso Reynard. He added a 138.6 mm (5.46 in) gun to the stern the ship could fire astern, and though the Conseil sought to have it removed, Eynaud prevailed. The Conseil also requested multiple engines for the single propeller shaft, like the Duquesne class, where one engine would be used for high-speed steaming and the other would be coupled for long-distance cruising. Pothuau approved the revised design on 10 March 1873, though his successor, Charles de Dompierre d'Hornoy revised the design again later that year and the final design was approved on 1 May 1874. The ship had already been ordered on 10 March 1873, and work had begun the following month, well before the design had been finalized.[4]

Duguay-Trouin's propulsion system proved to be much more serviceable than the chronically unreliable engines of the Duquesne class.[2] But like the Duquesnes, Duguay-Trouin was too expensive to build in large numbers, and so the French navy turned to smaller and cheaper vessels like the Lapérouse and Villars classes.[5][6]

Characteristics

Duguay-Trouin was an iron-hulled vessel that was 88 m (288 ft 9 in) long at the waterline and 90.15 m (295 ft 9 in) long between perpendiculars, with a beam of 13.2 m (43 ft 4 in). She had an average draft of 5.64 m (18 ft 6 in) on a displacement of 3,662 t (3,604 long tons; 4,037 short tons) as designed. The ship had a ram bow and an overhanging stern. Her hull was sheathed with wood to protect them from marine biofouling on long voyages overseas, and she was divided into nine watertight compartments, along with a double bottom. The ship rolled badly, but otherwise handled well. Her crew amounted to 311–322 officers and enlisted men.[2][7]

The ship's propulsion system consisted of three horizontal compound steam engines driving a single screw propeller. The engines were arranged in tandem, driving the same propeller shaft; the intent was for the forward engine to be used for high-speed steaming and the aft engine would be used for cruising at more economical speeds. Steam was provided by eight rectangular, coal-burning fire-tube boilers that were ducted into a pair of funnels placed amidships. The boilers were divided into two boiler rooms; the ship was intended to include fans for forced draft, but these were deleted in 1877 while the ship was still under construction. She had a full ship rig to supplement their steam engine on long voyages overseas, and the aft funnel could be retracted to allow full use of the sails, but she handled poorly under sail.[7][4]

Duguay-Trouin's machinery was rated to produce 3,500 indicated horsepower (2,600 kW) for a top speed of 15.5 knots (28.7 km/h; 17.8 mph). Coal storage amounted to 575.2 t (566.1 long tons; 634.0 short tons), and at a more economical speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), the ship was to have been able to steam for 6,500 nautical miles (12,000 km; 7,500 mi). But her boilers consumed coal at a much higher rate than anticipated to reach the intended howerpower, and in practice her cruising radius at that speed was significantly shorter, at 3,000 nautical miles (5,600 km; 3,500 mi).[2][7]

The ship's main battery consisted of five 194 mm (7.6 in) M1870 guns. One was placed in the bow under the forecastle deck and the remaining four were mounted in sponsons individually, two per broadside. The broadside guns were placed close to the ends of the ship to allow end-on fire. These were supplemented by a secondary battery of five 138.6 mm (5.46 in) 21.3-cal. M1870 guns; of these, one was mounted atop the sterncastle and the remaining four were placed amidships on the upper deck, firing through gun ports. For close-range defense against torpedo boats, she carried a pair of 37 mm (1.5 in) Hotchkiss revolver cannon.[2]

Modifications

In 1881, Duguay-Trouin was rearmed with longer-barreled M1881 versions of her main and secondary batteries. Her sailing rig was enlarged in December 1882, but it was found to hamper her stability while deployed, and so on 20 January 1883, her coal storage was reduced to 456 t (449 long tons; 503 short tons) to correct the problem. The alterations were still unsatisfactory, and on 24 June 1884, the navy ordered the ship to return to her previous rigging arrangement. The ship underwent a more significant reconstruction between 1885 and 1887, which included replacing her main battery guns with 164.7 mm (6.48 in) M1881 guns, and the sponsons were modified. The 138.6 mm guns were moved further apart to widen their firing arcs. The light armament was strengthened considerably, and it now consisted of two 65 mm (2.6 in) guns, four 47 mm (1.9 in) guns, and five 37 mm guns. Two 356 mm (14 in) torpedo tubes were also installed for M1885 torpedoes. Gun shields that were 4 mm (0.16 in) thick were fitted to all of the main and secondary guns, though the forward pair of 138.6 mm guns soon had theirs removed, as they were found to interfere with shell handling. The ship also received eight new boilers that increased the propulsion system's power to 4,800 indicated horsepower (3,600 kW); she reached a top speed of 15.78 knots (29.22 km/h; 18.16 mph) during tests carried out after the refit.[4][7]

Service history

The keel for Duguay-Trouin was laid down on 29 April 1873 at the Arsenal de Cherbourg shipyard in Cherbourg. She was launched on 31 March 1877 and her propulsion system was installed between 11 October that year and 31 May 1878. She was commissioned to begin sea trials on 26 July, but her crew had not been fully assembled until 28 November. Her initial testing was completed in January 1879, and she was placed in the 2nd category of reserve on 1 February. She remained out of service for the next three years before being recommissioned on 11 May 1882 to operate with the main fleet in French waters.[8] After it became apparent in 1883 that the large cruiser Tourville (of the Duquesne class) was unsuited to a lengthy deployment in East Asia, the navy decided to send Duguay-Trouin and the cruiser D'Estaing to replace her.[9] She had arrived in the region by March 1884, and at that time, the French fleet in the region also included the ironclad warships La Galissonnière (the flagship) and Triomphante, the unprotected cruisers D'Estaing, Villars, and Volta, and the gunboat Lutin.[10]

Sino-French War

France's campaign to occupy Vietnam, a traditional subject of Qing China, led to clashes between French and Chinese forces, and ultimately, to the start of the Sino-French War in August 1884 with the attack on Keelung on the island of Formosa early that month.Duguay-Trouin had been stationed at Fuzhou since mid-July, and initially had Rear Admiral Sébastien Lespès aboard; Lespès was the deputy commander of the Far East Squadron that had been created to support the Tonkin campaign. Lespès later transferred his flag to La Galissonnière. The unit was commanded by Vice Admiral Amédée Courbet. Following the action there, Courbet began assembling ships off Fuzhou to attack the Chinese Fujian Fleet that was stationed there. Despite the action at Keelung, relations between the Chinese and French fleet remained peaceful, though the Chinese began recalling vessels to Fuzhou to strengthen their position.[11]

Battle of Fuzhou

On the afternoon of 23 August, the French flotilla attacked the Chinese Fujian Fleet in the Battle of Fuzhou. Duguay-Trouni, D'Estaing, and Villars engaged the Chinese cruisers Feiyun and Ji'an and the gunboat Zhenwei, along with a coastal artillery battery. At the start of the action, Duguay-Trouin and Villars engaged Feiyun and Ji'an together while D'Estaing engaged Zhenwei. Duguay-Trouin and Villars quickly sank their targets, but Zhenwei put up unexpectedly stiff resistance and she was only sunk by the combined firepower of all three French vessels. The French ships then turned their attention to a shore battery that was neutralized shortly thereafter. The Chinese gunboat Jiansheng attempted to attack Duguay-Trouin, but heavy French fire set Jiansheng ablaze and she quickly exploded and sank. Another group of French warships also quickly destroyed or captured other elements of the Fujian Fleet further inside the harbor; the entire action lasted a mere eight minutes. Most of the battle was fought at very close range, roughly two to three cables.[12][13]

Over the night of 23–24 August, the Chinese sent several fire ships toward the French ships, forcing them to repeatedly shift position to evade them as they drifted down river. Courbet sought to destroy the arsenal facilities at Fuzhou and used his shallow-draft gunboats to bombard the fortifications around it on 24 August, that night, a pair of Chinese steam launches attempted to attack the French ships. Duguay-Trouin sank one of them. The next day, a 600-man landing party went ashore to complete the destruction of the facilities. Courbet then organized his fleet to leave the river, Triomphante in the lead, followed by Duguay-Trouin, Villars, and then D'Estaing, followed by the rest of the vessels. At this point, Courbet transferred his flag from the cruiser Volta to Duguay-Trouin. As the ships approached Couding near the mouth of the river, they needed to neutralize Chinese artillery batteries that blocked their exit. Triomphante and Duguay-Trouin engaged one set of batteries and drove off the gun crews. D'Estaing and Villars then sent a landing party ashore to destroy the guns. The French spent the night anchored off Couding and proceeded further downriver on 26 August; the forts at Mingan Pass were the next obstacle to reaching the open ocean. Again, Triomphante and Duguay-Troin led the attack on the fortifications.[14][15]

On 27 August, Duguay-Trouin covered a reconnaissance by a steam launch searching for Chinese junks that were being prepared to be scuttled at the mouth of the river, blocking the French escape. During the operation, Duguay-Trouin engaged in an artillery duel with one of the coastal batteries and was hit, but was not damaged. The attacks on coastal fortifications resumed on 28 August, and Duguay-Troin and other vessels sent landing parties ashore to destroy gun batteries blocking their progress downriver. By late on the 28th, the French had succeeded in destroying most of the coastal fortifications and; the next morning, Courbet took his ships down the last section of river and rendezvoused with La Galissonnière, which had been waiting to meet his ships since 25 August. Duguay-Trouin had to wait for high tide before she could depart for the Matsu Islands. The French victory at Fuzhou ended the initial diplomatic efforts to reach a compromise solution to the dispute over Tonkin, as the scale of the attack was such that the Chinese government could not ignore it.[16]

Operations off Formosa

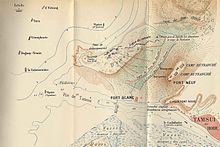

In the aftermath of Courbet's success at Fuzhou, the French debated several courses of action. Courbet and other naval officers favored strikes on the Chinese Beiyang Fleet in the Bohai Sea and raids on coastal targets that might compel the Chinese to surrender. But military commanders in France favored a more limited strategy focused on Formosa, and they ordered Courbet to carry out operations against Keelung and Tamsui on Formosa in late September. On 1 October, Courbet took his squadron to cover the landing at Keelung, and by 4 October, the port had been secured.[17] The next day, Courbet detached Duguay-Trouin and the cruiser Châteaurenault to support French forces engaged at the Battle of Tamsui, which were commanded by Lespès. Their landing parties, along with men from the ironclad Bayard, brought the total number of men available for the attack to 600.[18] The men landed the next morning, but the French proceeded slowly and failed to attack aggressively, which permitted the Chinese defenders to pin down the French, call for reinforcements, and then use the additional forces to attack the French flanks. Threatened with encirclement, the French fled to their boats, but the Chinese were unable to exploit their victory owing to gunfire from Lespès' ships. The French suffered a total of 17 deaths and 49 wounded in the defeat, despite inflicting roughly four times as many casualties on the Chinese.[19]

The French thereafter embarked on a blockade of Formosa on 20 October, while ground forces at Keelung waged a long battle with surrounding Chinese troops. These operations extended into January 1885, by which time the Chinese decided to try to block the blockade with the Nanyang Fleet. Courbet received word of the Chinese fleet's movements, and so he assembled a force to meet the Chinese vessels under Admiral Wu Ankang. Courbet's flotilla included Duguay-Trouin, the ironclads Bayard and Triomphante, and the cruisers Nielly and Éclaireur, and the gunboat Aspic. After several days of searching, Duguay-Trouin's fuel bunkers were running low, and so Courbet detached her to Keelung to refuel on 8 February, and so she missed the Battle of Shipu that took place on 13–14 February. [20]

On 25 February, Courbet left with several ships to blockade Shanghai to widen the economic impact of the blockade effort, while Duguay-Trouin remained off Formosa under Lespès, who continued to maintain the blockade of the island. At that time, she was stationed off Tamsui with the ironclad Atalante and the unprotected cruiser Duchaffault. The French blockade effort, which included other ports, proved to be effective at interrupting the movement of rice crops from southern China north. On 3 April, Duguay-Trouin briefly bombarded Chinese positions, killing two soldiers. These proved to be the last French shots fired at Formosa.[21] By this time, secret negotiations between French and Chinese representatives had already begun, as both countries were losing patience with the costly war, and in April, an agreement was reached that was formally signed on 9 June, ending the war.[22]

Later career

After the war ended, the French began to disperse the warships that had gathered in East Asia, and Duguay-Trouin and Châteaurenault were recalled to France.[23] After arriving home, she was taken into the shipyard at the Arsenal de Cherbourg for an extensive modernization that lasted from 1 November 1885 to 15 September 1887. She carried out speed testing on 11 April 1888.[2] In 1891, Duguay-Trouin was in reserve at Cherbourg, and she was mobilized to take part in the annual fleet maneuvers in June and July that year. At the time, the other ships at Cherbourg included the ironclad Turenne, the coastal defense ships Vengeur, Tonnerre, and Tonnant, the unprotected cruiser Fabert, the torpedo cruiser Epervier, and several smaller vessels. They did not participate in formal maneuvers, and each vessel went to sea individually to train their crews.[24][25]

In 1893, Duguay-Trouin was sent abroad again, this time to the Pacific station.[8] In August that year, one of the ship's 164.7 mm guns accidentally exploded during target practice while she was in Papeete, Tahiti. The shell that had been loaded into the gun exploded on the deck, and five men of the gun crew were seriously injured, of whom four died, though several others received less serious injuries. The gun was destroyed and Duguay-Trouin received significant damage from the explosion; parts of the gun were thrown as far as 76 m (250 ft).[26][27] In December 1894, Duguay-Trouin visited Yokohama, Japan, and fired salutes to mark her visit.[28] The ship was transferred to French Indochina in 1895, where Bayard still served as the squadron flagship. The unit also included the protected cruisers Isly and Alger and the unprotected cruisers Forfait and Beautemps-Beaupré [29]

By 1898, Duguay-Trouin had been transferred back to the Pacific station, but late that year she was sent to Chinese waters in response to the Boxer Uprising; many foreign navies sent naval forces to defeat the Boxers, and by the end of the year, the French contingent also included the protected cruisers Descartes, Pascal, and Jean Bart.[30] She later moved to French Indochina, where she served until 25 November 1899, when she was struck from the naval register. She was renamed Vétéran on 25 May 1900. She was then towed to Rạch Dừa, where she was converted into a depot ship for the 1st Torpedo Boat Flotilla, replacing the old gunboat Cimeterre in that role. The unit was stationed in Rạch Dừa, and Vétéran remained there until 1910. She was listed for sale in July, and was sold to ship breakers in Saigon on 12 September 1911.[8]

Notes

- ^ Ropp, p. 39.

- ^ a b c d e f Roberts, p. 107.

- ^ Roberts, pp. 96–97, 107.

- ^ a b c Roberts, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Ropp, p. 109.

- ^ Roberts, pp. 108–110.

- ^ a b c d Campbell, p. 317.

- ^ a b c Roberts, p. 108.

- ^ Olender, p. 15.

- ^ Loir, p. 5–6.

- ^ Olender, pp. 38–42.

- ^ Olender, pp. 42–53.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 4–9.

- ^ Olender, pp. 55–58.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Olender, pp. 58–60.

- ^ Olender, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Garnot, pp. 50–53.

- ^ Olender, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Olender, pp. 72–80.

- ^ Davidson, p. 237.

- ^ Olender, pp. 84–86, 101.

- ^ Loir, pp. 351–352.

- ^ Thursfield, p. 62.

- ^ Bursting of a Gun.

- ^ Glennon, p. 626.

- ^ The French Cruiser.

- ^ Brassey 1895, p. 54.

- ^ Brassey 1898, pp. 59–60.

References

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1895). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 49–59. OCLC 496786828.

- Brassey, Thomas A. (1898). "Chapter III: Relative Strength". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 56–66. OCLC 496786828.

- "Bursting of a Gun on a French Cruiser". Japan Daily Mail. 21 October 1893.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1979). "France". In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 283–333. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Davidson, James Wheeler (1903). The Island of Formosa: Historical View from 1430 to 1900.

- Garnot, Eugène Germain (1894). L' expédition française de Formose, 1884–1885 [The French Expedition to Formosa, 1884–1885] (in French). Paris: Librairie C. Delagrave. OCLC 3986575.

- Glennon, J. H., ed. (1894). "Professional Notes". Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute. XX. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press: 605–643.

- Loir, M. (1886). L'escadre de l'amiral Courbet, notes et souvenirs [The Squadron of Admiral Courbet, Notes and Memories] (in French). Paris: Berger-Levrault. OCLC 457536196.

- Olender, Piotr (2012). Sino-French Naval War 1884–1885. Sandomir: Stratus. ISBN 978-83-61421-53-5.

- Roberts, Stephen (2021). French Warships in the Age of Steam 1859–1914. Barnsley: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-5267-4533-0.

- Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-141-6.

- "The French Cruiser". Japan Daily Mail. 8 December 1894.

- "The French Naval Manoeuvres of 1891". Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. XXXV (164). London: J. J. Keliher & Co.: 1102–1108 October 1891. OCLC 1077860366.

- Thursfield, J. R. (1892). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). "Foreign Naval Manoeuvres". The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 61–88. OCLC 496786828.

- Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare from 1855 to 1895. London: S. Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 1111061.