Contents

Howard Russell Butler (March 3, 1856 – May 20, 1934)[1] was an American painter and founder of the American Fine Arts Society.[2] Butler persuaded Andrew Carnegie to fund the construction of Carnegie Lake near Princeton University,[3] supervised the construction of the Carnegie Mansion, designed an astronomy hall, and painted a solar eclipse for the U.S. Naval Observatory.[4]

Biography

Science, law and art

Butler was born in New York City. He was the son of William Allen Butler, a lawyer and satirist.[5] His early artistic training with William Shannon was complemented by visits to the National Academy of Design, where his parents were both fellows, and the studio of his uncle, William Stanley Haseltine.[6]

Butler attended Princeton University and obtained a degree in Science in 1876 and he was invited to stay on for a year as an assistant professor of physics. From 1878 to 1879 he was doing technical illustrations in New York where he knew Thomas Edison.[6] In 1881 he graduated from Columbia University where he had studied law.[2] Whilst he was at Princeton he was an active member of the rowing team despite there being poor facilities. Butler practiced patent law until 1884 when he decided to concentrate entirely on painting.

Art and leadership

Butler reapplied himself studying under Frederic Edwin Church, who was wintering in Mexico for his health, in January 1884[7] before returning to study with J. Carroll Beckwith and George de Forest Brush at the Art Students League in New York.[6] In 1885, he went to France for two years and lived in Paris, a member of the artistic American colony in Paris, and Concarneau.[8]

In 1889 Butler was able to find the capital to build the Fine Arts building at 215 West 57th Avenue. This building was to be the home of the Art Students League, the Society of American Artists, the Architectural League of New York and the newly formed American Fine Arts Society which Butler led for its first 17 years. Whilst raising these funds he first met Andrew Carnegie who employed him for ten years as president of the Carnegie Music Hall Company allowing him time off each day to paint. Butler married his wife Virginia Hays in 1890.[6]

By 1899 he was a National Academician of the National Academy of Design and a member of the Architectural League and the Society of American Artists.[9]

Art and Carnegie Lake

In 1902 he was invited to join the Society of Artists[2] and he was asked to make another portrait of the philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. Whilst Carnegie was sitting for the portrait, the problem of finding places to row at Princeton was discussed. Carnegie noted that Scottish lochs were created by just constraining the flow of water. Butler and the rowing team had just such a scheme in mind to create an artificial lake. With Carnegie's permission, Butler contacted a building firm in his home town and obtained an estimate of US$118,000 to construct a lake. Lake Carnegie and the purchase of hundreds of acres of land resulted from this meeting.[3]

It was while employed by Carnegie that Butler supervised the construction of Carnegie's mansion on Fifth Avenue, which was designed by Babb, Cook, & Willard and is now the Cooper-Hewitt Museum,[10] but he and Carnegie differed and Butler left his employ in 1905.[6]

From 1905 until 1907 he was in California and again in the early 1920s when he was living at Pasadena and Santa Barbara. He may therefore have missed the opening of the lake in 1906 that was three and a half miles long and eight hundred feet wide. It was reported that President Wilson tried to later persuade Carnegie to give funds to Princeton but he was told that he had already given a lake. Wilson is reputed to have said, "We needed bread and you gave us cake."[3]

Solar eclipse and art

In 1918, Butler's association with Carnegie led to him being invited to witness and record the 1918 Solar eclipse that was observed from Baker City in Oregon. The expedition was organized by the U.S. Naval Observatory and included Samuel Alfred Mitchell as its expert on eclipses. Butler noted later that he used a system of taking notes of the colors using skills he had learned for transient effects. Usually a sitting for a portrait took two hours but an eclipse would take just over 112 seconds. It has been noted that he had painted Carnegie thirteen times[11] and like the eclipse he could never keep still to allow Butler to make considered notes.[4] His revived interest in physics led to his 1923 book Painter and Space which coincided with his second visit to a solar eclipse. He also created pictures of planets that were as seen from one of their moons. His last known eclipse visit was in 1932.[6]

Butler is known particularly for paintings of seascapes and for his views of the eclipse of the sun, but he also painted people and landscapes.[2] Butler also designed an Astronomy Hall for the American Museum of Natural History. Butler's paintings of solar eclipses were on display for many years at the Hayden Planetarium at that museum.[4]

Landscapes for the National Park Service

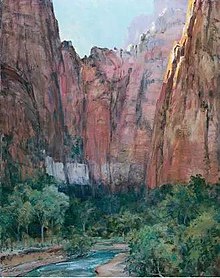

In 1926, the Union Pacific Railroad commissioned Butler to paint a series of landscapes for promotion of the Colorado Plateau and its scenic marvels as a part of the Union Pacific Railroad “Grand Circle Tour”. He completed seven large paintings of Zion National Park and one of Grand Canyon National Park. These paintings were used in a traveling exhibit by the Union Pacific to promote tourism in the region. They represent the early history of the establishment of Zion and Grand Canyon as well as early tourism promotion in Utah. The paintings were also on exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History. By 1929 they reached the Museum of Science in Buffalo, NY for display. Eventually, the canvases were relocated to storage. In 1998/99, their registrar discovered the paintings and donated them to Zion National Park and Grand Canyon National Park. The paintings are nationally significant as they represent the early period of National Park Service development of visitor recreation and transportation.[12]

Butler died in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1934 near the lake that he had organized for their rowing team. His work can be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum,[2] American Museum of Natural History[9] and of course Carnegie Lake.

-

Howard Russell Butler : Les Ramasseurs de varech (1886) (near Concarneau)

References

- ^ "PAINTER BUTLER DIES" (23 May 1934) Los Angeles Times

- ^ a b c d e Hughes, Edan. "Howard R. Butler". edanhughes.com. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Leitch, Andrew Alexander. "Carnegie Lake". A Princeton Companion 1978. Princeton University Press. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Lawrence, Jenny; Richard Milner (February 2000). "A Forgotten Cosmic Designer". Natural History. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Butler, William Allen (October 2009). A Retrospect of Forty Years, 1825-1865 p.427. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 9781115396691.

- ^ a b c d e f Dearinger, David Bernard (2004). Paintings and Sculpture in the Collection of the National Academy of Design 1826-1925... p.78. National Academy of Design. ISBN 9781555950293.

- ^ Carr, Gerald L. (1994). Frederic Edwin Church: Catalogue Raisonne of Works at Olana State Historic Site, Volume I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 420. ISBN 978-0521385404.

- ^ http://www.concarneau-peintres.fr/etranger/americains/butler.htm [dead link]

- ^ a b "Howard Russell Butler". Artnet.com. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Andrew Carnegie Mansion". National Park Service. 1975-05-30.

- ^ Another source says 17 times

- ^ "Howard Russell Butler - Zion National Park (U.S. National Park Service)".