Contents

The Phillis Wheatley Clubs (also Phyllis Wheatley Club) are women's clubs created by African Americans starting in the late 1800s. The first club was founded in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1895. Some clubs are still active. The purpose of Phillis Wheatley Clubs varied from area to area, although most were involved in community and personal improvement. Some clubs helped in desegregation and voting rights efforts. The clubs were named after the poet Phillis Wheatley.

About

Phillis Wheatley Clubs worked on improving their neighborhoods and the lives of people in their communities.[1] Clubs were also involved in social reform.[2] In New Orleans, the Phyllis Wheatley Club founded the only training hospital for black doctors and nurses in 1896.[3] The hospital was originally named the Phyllis Wheatley Sanitarium and Training Hospital for Nurses.[3]

The Chicago club was founded in 1896 by a group of Black women led by Elizabeth Lindsay Davis, and created a home for young women without permanent housing.[4][5] It was the first Black women's club formed in Chicago,[5] and was supported by Mary Jane Richardson Jones, a prominent older black activist and wealthy widow.[6][7] The first Phyllis Wheatley Home, located on Chicago's South Side, was purchased for $3,400 in 1906, and Jennie Lawrence was hired to oversee it.[5] It opened in 1908, and served as a settlement house, providing accommodations to Black women during the Great Migration.[5][8] It moved into a larger building in 1913, before moving to its final location on South Michigan Avenue in the mid-1920s.[8][5] It remained open until the 1970s.[5] The first two locations have been demolished, while a hearing in demolition court is scheduled for its final location on March 16, 2021.[5] However, its owner is hoping to restore the building and create a public exhibit space on Black women's history.[8] Preservation Chicago listed the last Chicago Phyllis Wheatley Club and Home as one of Chicago's 7 most endangered buildings in February 2021.[5][9]

The New Orleans club, which was founded by Sylvanie Francoz Williams, also opened a kindergarten and day care for working women and the club was also involved in black women's suffrage.[10] The club in Nashville, Tennessee purchased a home for older women in 1925.[11] The Billings, Montana club was instrumental in helping desegregate the city.[12] The Billings club also sponsored scholarships for young women.[12] Clubs, such as the Phyllis Wheatley Progressive Club in Pennsylvania, opened a night school in the late 1920s.[13]

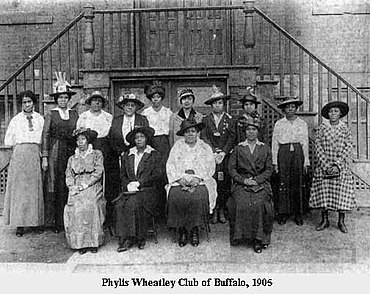

Some clubs also emphasized continued learning.[14] The Phyllis Wheatley Club in Chicago also emphasized black literature.[15] Clubs also donated books in celebration of Black History Month to public libraries.[16] Atlanta's club helped build a reading room, also named after Phiillis Wheatley.[17] In Buffalo, the Phyllis Wheatley Club there celebrated the 30th anniversary of the ending of slavery with a play which they sponsored.[18] The club in Racine, Wisconsin in 1921 brought in Maud Cuney Hare and William H. Richardson to perform to show off black talent.[19] The Charleston, South Carolina club hosted events featuring prominent individuals in the black community such as Marian Anderson, Mary McCleod Bethune, Countee Cullen, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Langston Hughes.[20] The club in Coshocton, Ohio, also promoted black figures in history, creating a program that featured individuals and inviting other clubs to attend the even annually.[21]

To pay for charity work and other endeavors, the clubs held fundraisers. These could be in the form of balls or dances, or theater and musical receptions.[22][23] In Tampa Bay, the Phyllis Wheatley Club sponsored an annual "Defense Dance" which raised money by charging a fee at the door.[24] Fundraising could go towards other non-profit groups, such as the NAACP.[20]

Clubs could be affiliated with the YWCA or worked independently.[25] The first club, started in Nashville, became affiliated with the National Federation of Colored Women's Clubs (NFCWC) in 1897.[11] Other clubs, such as the Fort Worth Phyllis Wheatley Club, were also affiliated with the NFCWC.[26]

Early club members were normally professional women or married to "prominent men in the community."[14] However, some Phillis Wheatley Clubs were made up of younger members.[27] Other clubs had members of many different demographics.[12][21] Clubs were named for the poet, Phillis Wheatley.[20] Many clubs have been and are still active into the 21st century. The El Paso, Texas Phillis Wheatley Club celebrated its 90th anniversary in 2005.[28]

Early history

1890s

The first Phillis Wheatley Club was created in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1895.[25] Another club was formed in Chicago in 1896 and focused on neighborhood improvements and charity work.[1][29] It was founded by Elizabeth Lindsay Davis and was one of the first groups for African American women in the city.[30] Detroit's Phillis Wheatley Club was started in 1897.[25] Mame Josenberger, who founded the Phillis Wheatley Club in 1898 in Fort Smith, Arkansas, would go on to later serve as president of the Arkansas Association of Colored Women (AACW).[31]

1900s

The Newark, New Jersey Phillis Wheatley Club was founded in 1909 with a focus on literature.[32] Musette Brooks Gregory, a suffragist and civil rights advocate, served as one of the elected presidents of the Newark Club.[33]

1910s

In Cleveland, Jane Edna Hunter founded a group in 1911 that was later renamed the Phillis Wheatley Association.[34][35] The El Paso, Texas Phillis Wheatley Club was started in 1915.[28] Charleston, South Carolina started a club in 1916 which was named the Phillis Wheatley Literary and Social Club.[36] Another club was founded in 1918 in Billings, Montana, and the first president was Mattie Hambright.[12] The Billings club would continue until 1972.[12] Dora Bell started a club in Racine, Wisconsin in 1919.[37] The Fort Scott, Kansas club was started in 1919 to "study current topics, civics and economics."[38]

1930s

In 1932, a club in Passaic, New Jersey, worked to raise $5,000 for the creation of a black community center.[39] The Coshocton, Ohio, club was started in 1933 a few months just before the 159th anniversary of the publication of Poems by Wheatley.[21] The Coshocton club was affiliated with the YWCA and started by Thelma Crowthers.[21]

Notable members

- Jane Edna Hunter, founder of the Cleveland group.[35][34]

- Mame Josenberger, founder of the Fort Smith, Arkansas group.[31]

- Vivian Osborne Marsh.[40]

- Drusilla Nixon.[41]

- Mary Burnett Talbert, one of the founding members of the Buffalo, New York group.[42]

- Sylvanie Francoz Williams, founder of the New Orleans club.[10]

See also

References

- ^ a b Lerner 1974, p. 161.

- ^ Knupfer 1997, p. 224.

- ^ a b Hine, Darlene Clark; Thompson, Kathleen (1996). Facts on File encyclopedia of Black women in America. Vol. 11. New York: Facts on File. pp. 7. ISBN 0816034249 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Knupfer 1997, p. 227.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Phyllis Wheatley Home Chicago 7 2021", Preservation Chicago. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- ^ Guzman, Richard (2006). Black writing from Chicago : in the world, not of it?. Carolyn M. Rodgers. Southern Illinois University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-8093-2703-1. OCLC 62324505.

- ^ Hendricks, Wanda A. (2013). Fannie Barrier Williams: Crossing the Borders of Region and Race. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-09587-0. OCLC 1067196558.

- ^ a b c Ihejirika, Maudlyne (February 23, 2021). "Owner, supporters fight to save historic Phyllis Wheatley Club and Home from city demolition block". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ Keilman, John. "Chicago lakefront, Catholic churches top newest list of city's most endangered historic buildings", Chicago Tribune. February 24, 2021. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- ^ a b "Sylvanie Francoz Williams". Voices of Progress · The Historic New Orleans Collection – Digital Exhibits. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ a b Mielnik, Tara Mitchell. "Phillis Wheatley Club". Tennessee Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Pickett, Mary (February 20, 2010). "Black women's group alters treatment of minorities in Billings". The Billings Gazette. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "Progressive Club Has Organized Night School". The Daily Notes. January 15, 1927. Retrieved May 24, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Knupfer 1997, p. 223.

- ^ Knupfer 1997, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Aboytes, Yasmin A. (February 14, 1971). "Phillis Wheatley Club Donates Library Book". El Paso Times. Retrieved May 21, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bois, William Edward Burghardt Du (1909). Efforts for Social Betterment Among Negro Americans: Report of a Social Study Made by Atlanta University Under the Patronage of the Trustees of the John F. Slater Fund; Together with the Proceedings of the 14th Annual Conference for the Study of the Negro Problems, Held at Atlanta University on Tuesday, May the 24th, 1909. Atlanta University Press. pp. 53.

phillis wheatley club.

- ^ "Immense Production by Negroes". Buffalo Courier. April 14, 1901. Retrieved May 20, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Phyllis Wheatley Club Will Give Fine Concert". The Journal Times. December 28, 1921. Retrieved May 20, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Whitneyal (March 25, 2013). "Ongoing Exhibit: The Phillis Wheatley Literary and Social Club: Fostering Civic Engagement, Intellectual Exchange and Female Solidarity". Not Just in February. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Reisman, Deborah (January 29, 1978). "PHillis Wheatley Club". The Tribune. Retrieved May 24, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Knupfer 1997, pp. 228–229.

- ^ "Special! Extra! Special! A Benefit Performance". The Broad Ax. February 2, 1907. Retrieved May 20, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Phyllis Wheatley Club Has Springtime Defense Dance". Tampa Bay Times. June 14, 1942. Retrieved May 20, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Anderson, Meg (May 17, 2009). "Phyllis Wheatley Women's Clubs (1895– ) • BlackPast". BlackPast. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ Winegarten, Ruthe (June 13, 2010). "Texas Association of Women's Clubs". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ Williamson, Jerrelene (2010). African Americans in Spokane. Arcadia Publishing. p. 59. ISBN 9780738570112.

- ^ a b "Phillis Wheatley Club Anniversary". El Paso Times. May 29, 2005. Retrieved May 21, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Knupfer 1997, p. 222.

- ^ Knupfer 1997, p. 221.

- ^ a b Jones-Branch, Cherisse. "Arkansas Association of Colored Women". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ "Phillis Wheatley Club Hears Pansy Borders". The Montclair Times. March 19, 1959. Retrieved May 24, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hendrickson, Lisa (2019). "Biography of Musette Brooks Gregory, 1876–1921". Alexandria Street. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ^ a b Lerner 1974, p. 162.

- ^ a b "Hunter, Jane Edna (Harris)". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Case Western Reserve University. February 12, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ "Inventory of the Phillis Wheatley Literary and Social Club Papers, 1916 – 2011". Avery Research Center. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ Murdoch, Mary (March 4, 1999). "Remarkable Women Honored During March". The Journal Times. Retrieved May 20, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "At the Churches". Fort Scott Daily Tribune-Monitor. December 31, 1921. Retrieved May 24, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Phyllis Wheatley Club in Drive for $5,000". The Herald-News. April 8, 1932. Retrieved May 29, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Who's Who in Colored America (Yenser 1942): 355.

- ^ "Phillis Wheatley Club Names Woman of the Year". El Paso Times. June 4, 1978. Retrieved May 31, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Talbert timeline". African American History of Western New York. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

Sources

- Knupfer, Anne Meis (Spring 1997). "'If You Can't Push, Pull, If You Can't Pull, Please Get Out of the Way': The Phyllis Wheatley Club and Home in Chicago, 1896 to 1920". The Journal of Negro History. 82 (2): 221–231. doi:10.2307/2717517. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2717517. S2CID 140411339.

- Lerner, Gerda (April 1974). "Early Community Work of Black Club Women". The Journal of Negro History. 59 (2): 158–167. doi:10.2307/2717327. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2717327. S2CID 148077982.